Associations of Maternal Emotional Intelligence and Coping Strategies with Diabetes Management in Adolescents with Type-1 Diabetes

Received: 05-Apr-2024 / Manuscript No. JCPHN-24-131563 / Editor assigned: 08-Apr-2024 / PreQC No. JCPHN-24-131563 (PQ) / Reviewed: 22-Apr-2024 / QC No. JCPHN-24-131563 / Revised: 23-Apr-2024 / Published Date: 30-Apr-2024

Abstract

Purpose: The aim of the study was to assess the association of mothers' emotional intelligence and coping strategies with diabetes management in adolescents with Type-1diabetes.

Design and methods: Mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes (aged 12-17 years) participated in the study (n=75). The following questionnaires were used: TEI Que-SF and Brief-COPE with additional questions about diabetes management and socio–demographic questions. The primary indicator of diabetes management was glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Data was collected via paper questionnaire and through an online survey in 2023.

Results: Mothers whose child had optimal diabetes management showed higher emotional intelligence sociability traits than mothers whose child had poor diabetes management (p =0.029). Coping strategies were not statistically significantly associated with diabetes management in adolescents with Type-1 diabetes (p >0.05). Finally, higher emotional intelligence of mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes was found to be statistically significantly associated with problem-focused coping (rho =0.669, p<0.001) and emotion-focused coping (rho = 0.321, p =0.005), while lower emotional intelligence was statistically significantly associated with avoidant coping (rho = -0.434, p <0.001).

Conclusions: The sociability trait of emotional intelligence was higher in mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes when the child had optimal diabetes management. Higher maternal emotional intelligence predicted problemfocused and emotion-focused coping, whereas lower emotional intelligence predicted avoidant coping.

Practical implication: The development of the sociability trait of emotional intelligence could improve maternal functioning in social contexts and act as a mediator for better diabetes management.

Keywords

Type-1 diabetes; Emotional intelligence; Coping strategies; Diabetes management

Introduction

Type-1 diabetes mellitus (1TDM) is an autoimmune chronic disease that results from the destruction of the pancreatic β-cells, which causes insulin deficiency in the human body [1]. It is one of the most common chronic diseases in children and adolescents. According to the latest data, more than 1.2 million children and adolescents (up to 19 years of age) worldwide are living with a diagnosis of Type-1 diabetes [2].

1TDM is an incurable but manageable chronic disease. The disease requires constant work, control and significant internal resources to prevent serious health complications such as cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, lower limb amputation and vision problems [2]. Managing the disease requires daily insulin injections, measuring blood glucose (glycaemia), counting carbohydrates in food, and monitoring and limiting physical activity. The demands of the disease are incompatible with the child's psychosocial maturity and therefore require adult support, i.e. parental help.s

Managing the disease is a difficult daily task that psychologically affects not only the patient, but also their parents. Studies show that severe generalised anxiety affects 13% of adolescents with 1TDM and as many as 47% of their parents [3]. Parents help to manage the illness from the very beginning and become an integral part of controlling the illness as the child grows. It has been observed that adolescence can present additional challenges in diabetes management. In this paper, adolescence is considered as the period from 12 to 17 years. Studies show that only 17% of adolescents maintain the recommended thresholds for diabetes management [4]. Poorer diabetes management increases the risk of health complications. It is also associated with higher rates of psychiatric disorders in adolescents [5] and higher rates of parental depression and distress [6,7].

1TDM requires parents to put significant internal resources into helping their child maintain good control of the disease. Emotional intelligence can play an important role in controlling 1TDM and coping with the various challenges posed by the disease. In this paper, emotional intelligence (EI) is treated as the trait model proposed by Petrides and Furnham [8]. The trait model of EI "describes our perception of our emotional world: what our emotional dispositions are and how good we believe we are at perceiving, understanding, managing, and using our own and other people's emotions" [9]. Individuals with high EI trait patterns have been found to be able to tolerate high-pressure situations and control their emotions well [10]. In recent years, EI has received increasing attention. In the context of 1TDM management, high levels of parental emotional intelligence are associated with better disease control [11]. High parental EI may help to better manage the stress and emotions associated with caring for a child with 1TDM and controlling the disease. However, Žilinskienė et al. [12] found that higher EI among mothers was actually associated with worse diabetes management in their children. The association of parental EI with their children's HbA1c is an understudied topic. Existing studies show conflicting results. Further research is needed to fully draw conclusions and understand the relationship between EI and 1TDM management.

Coping strategies can also play an important role in coping with the various challenges and problems posed by the disease. Coping strategies are defined as the emotional, behavioural and cognitive efforts undertaken by an individual to cope with specific external or internal demands that are perceived to be beyond the individual's resources [13]. There are different types of coping strategies, including problem-focused coping (attempting to solve the problem directly), emotion-focused coping (attempting to manage the emotions associated with the problem), and avoidance-focused coping (attempting to avoid or ignore the problem). In the context of 1TDM management, parents who use problem-focused coping strategies may be more likely to effectively manage their child's blood sugar levels and prevent complications, while those who use avoidance-focused coping strategies may be less effective in managing their child's disease. Research has shown that parents' avoidance-focused coping strategies have been associated with poorer management of their children's diabetes [14]. However, a study by Jaser et al. [15] found no statistically significant association between coping strategies and diabetes management. There are still not enough articles to be able to summarize the results and formulate conclusions. This is a little researched topic. Understanding this relationship would help to understand how coping strategies affect diabetes managagement, which in turn would help in better illness management.

Emotional intelligence is an important skill for coping with the challenges of everyday life and for effectively managing relationships with other people. When a person has a high level of EI, he or she is better able to cope with life's challenges and problems. Studies have shown that high EI is also associated with the selection of adaptive coping strategies [16]. These coping strategies can help people to break down large, difficult problems into smaller, more manageable tasks, and to develop possible solutions and to implement and choose the best solution. In the context of 1TDM, this could contribute to better diabetes management, but there is a lack of research in this area.

As many research studies have shown, 1TDM directly affects not only the emotional health and functioning of the child, but also of the parents. Parental emotional intelligence and coping strategies can play an important role in the management of 1TDM and the various challenges of the disease. Due to the lack of research in this area, it is not yet known exactly how emotional intelligence and coping strategies interact with the control of 1TDM. Thus, the present study aimed to assess the relationship between maternal emotional intelligence, coping strategies and disease control in adolescents with Type-1 diabetes.

Methods

Design and participants

A quantitative study was carried out in 2023. The study was carried out at the Endocrinology Clinic of Kaunas Clinics, LSMU Hospital. The survey was also conducted online due to the complexity of reaching the survey sample and in order to collect a larger sample of people. An invitation to participate in the study and an anonymous questionnaire were posted on a Facebook group for parents of children with Type-1 diabetes. Mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes (aged 12-17 years) whose child was diagnosed with Type-1 diabetes exactly or more than 1 year ago participated in the study. A total of 85 people completed the questionnaire and 75 participants met the criteria.

Instruments

An anonymous questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire consisted of socio-demographic and disease management questions and two questionnaires.

Diabetes management indicator: To assess diabetes management, the results of the last glycated haemoglobin test (HbA1c) were requested [16]. HbA1c was categorized according to the American Diabetes Association (2021) recommendations into an optimal glycaemic control group with HbA1c < 7.0% and a poor glycaemic control group with HbA1c ≥ 7.1%.

Emotional intelligence: The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire - Short Form (TEIQue-SF) was chosen to assess emotional intelligence [17]. The questionnaire consists of 30 statements, where respondents had to rate the statements on a scale from 1 - "strongly disagree" to 7 - "strongly agree". The trait EI model questionnaire consists of fifteen personality dimensions grouped into four subscales:

Well-being: This subscale includes a general sense of well-being, the ability to manage one's emotions, and to maintain a positive outlook on life.

Self-control: This subscale covers how well a person is able to control impulses and emotions, resist temptations and cope with external pressures and stress.

Emotionality: This subscale covers the ability to recognise and express one's own emotions, as well as to empathise with the emotions of others and to foster and maintain good relationships with others.

Sociability: This subscale defines the ability to build and maintain positive relationships with others, to communicate effectively and to cooperate in groups.

The overall internal consistency of the questionnaire is very good (Cronbach α = 0.869). Internal consistency is good for all subscales (α >0.6), except for the Sociability scale, which does not have high internal consistency but is adequate (α =0.548)

Coping strategies: The Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory (Brief-COPE) questionnaire was used in this study [18]. The questionnaire consists of 28 statements where respondents were asked to rate how often they use the given coping strategies. Each statement was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 means 'never' and 4 means 'very often'. There are 14 coping strategies, which are grouped according to their orientation: problem-focused coping (attempting to solve the problem directly), emotion-focused coping (attempting to manage the emotions associated with the problem), and avoidance-focused coping (trying to avoid or ignore the problem). The mean of each subscale was calculated. The higher the score, the more frequently the coping strategy is used.

The internal consistency of the questionnaire is very good (Cronbach α = 0.815). Internal consistency for all subscales was high (α ≥0.7).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS 29 statistical package for data analysis. Before the analysis, the normality of the distribution of the data was assessed by the coefficients of excess and asymmetry (a distribution is considered normal when the absolute values of the asymmetry and excess are <1). In the descriptive data analysis, absolute numbers (N) and percentages of response rates were calculated for nominal and rank variables. For continuous variables, asymmetry and excess coefficients were calculated. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for normally distributed variables and medians and interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed variables.

In bivariate analysis, the Spearman correlation coefficient was used to show correlation. For comparisons by diabetes management group, the Student's T criterion was applied to continuous and normally distributed variables, and the Mann-Whitney independent samples criterion was applied to continuous and non-normally distributed variables and rank variables. The reliability of the data was considered significant when p < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

Permission was obtained from the Bioethics Centre to conduct the study. All ethical principles were observed during the study.

Results

Table 1 describes the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of all participants and their children.

| Variable | N | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 75 | 96.2 | |

| Male | 0 | 0 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 57 | 76.0 | |

| Divorced | 11 | 14.7 | ||

| Living alone | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| Widowed | 0 | 0 | ||

| Single mother | 6 | 8 | ||

| Employment status | Working | 69 | 92.0 | |

| Not working | 6 | 8.0 | ||

| Material situation | Very good | 11 | 14.7 | |

| Good | 39 | 52.0 | ||

| Fair | 23 | 30.7 | ||

| Poor | 2 | 2.7 | ||

| Very bad | 0 | 0 | ||

| Gender of the child with Type-1 diabetes | Daughter | 33 | 44.0 | |

| Son | 42 | 56.0 | ||

| Diabetes management (based on HbA1c) | Optimal | 44 | 58.7 | |

| Poor | 31 | 41.3 | ||

| Mean | Standard deviation | Asymmetry | Excess | |

| Participants age | 43.2 | 5.44 | 0.46 | -0.18 |

| Duration of illness | 5.3 | 3.28 | 0.68 | -0.27 |

| Median | Interquartile range | Asymmetry | Excess | |

| Age of child with Type-1 diabetes | 14 | [12 ; 16] | 0.33 | -1.27 |

| HbA1c (indicator of disease control) | 6.8 | [6.2 ; 7.6] | 1.00 | 1.80 |

Table 1: Distribution of Participants by Socio-demographic Characteristic.

A review of the EI scores showed that mothers of adolescents with 1TDM had higher emotional intelligence than the theoretical average of 3.5. The most pronounced trait of emotional intelligence was a general sense of well-being, compared to emotionality, self-control and sociability. The least expressed trait of emotional intelligence was sociability. Detailed subscale expression rates are shown in the Table 2.

| Subscale | Mean item score | Mean scale score |

|---|---|---|

| General emotional intelligence | 5.1 (SD = 0.70) | 153.3 (SD = 21.08) |

| Well-being | 5.6 (SD = 0.95) | 33.8 (SD = 5.73) |

| Self-control | 4.8 (SD = 0.99) | 28.9 (SD = 5.96) |

| Emotionality | 5.1 (SD = 0.90) | 41.3 (SD = 7.17) |

| Sociability | 4.6 (SD = 0.72) | 27.6 (SD = 4.34 |

Table 2: Trait Emotional Intelligence of Mothers of Adolescents with 1TDM.

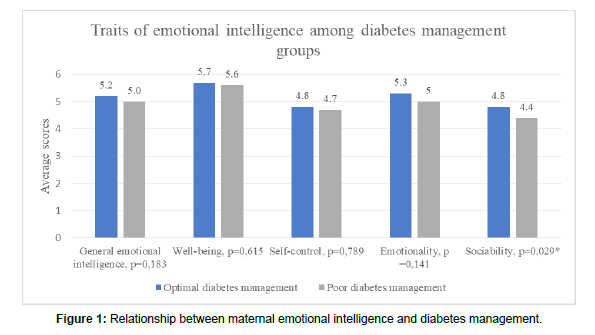

When looking at the EI between the different diabetes management groups, there was no statistically significant difference in the overall EI score between groups. However, on the subscales, parents whose child had optimal disease control had more pronounced sociability traits than parents whose child had poor disease control (Figure 1). This means that parents whose child has optimal control of the illness are better listeners, have a more pronounced ability to interact with a variety of people and are able to have more effective interactions with others (Figure 1).

When analyzing the coping strategies most commonly used by mothers (Table 3), the most prominent coping strategies were problem-focused and emotion-focused. The least frequently used coping strategy was the avoidance-oriented coping strategy. This indicates that when faced with stressful situations, the participants are reluctant to ignore the situation and do not try to escape from it (Table 3).

| Subscale | Mean item score | Mean scale score |

|---|---|---|

| Problem-focused coping | 2.9 (SD = 0.55) | 23.6 (SD = 4.38) |

| Emotion-focused coping | 2.3 (SD = 0.43) | 27.3 (SD = 5.22) |

| Avoidant coping | 1.7 (SD = 0.48) | 13.5 (SD = 3.85) |

Table 3: Indicators of Coping Strategies among Mothers of Adolescents with 1TDM.

When looking at coping strategies by diabetes management group, there were no statistically significant differences in coping strategies between diabetes management groups. The subscale scores were also not significantly different, but it can be noted that parents with a child with poor diabetes management are more likely to use avoidance-oriented coping, but this is not statistically significant. Further details are given in the Table 4.

| Coping strategies | Diabetes management | Average rank | U | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General coping strategies | Optimal | 37.51 | 660.50 | 0.817 |

| Poor | 38.69 | |||

| Problem-focused coping | Optimal | 38.98 | 639.00 | 0.642 |

| Poor | 36.61 | |||

| Emotion-focused coping | Optimal | 38.10 | 677.50 | 0.961 |

| Poor | 37.85 | |||

| Avoidant coping | Optimal | 35.49 | 571.50 | 0.231 |

| Poor | 41.56 |

Table 4: Differences in mean Coping Strategies among Mothers of Adolescents with 1TDM in Different Diabetes Management Groups .

The results of the correlation analysis between EI and coping strategies showed a statistically significant correlation between total EI and coping strategies. General EI was statistically significantly correlated with coping strategies (rho = 0.280, p = 0.015). EI was negatively correlated with avoidance-focused coping strategies (rho = -0.434, p<0.001) and positively correlated with problem-focused (rho = 0.669, p<0.001) and emotion-focused (rho = 0.321, p = 0.005) coping strategies. This suggests that adaptive coping strategies, i.e. problem-oriented and emotion-oriented coping strategies, are more prevalent at higher EI scores. Conversely, the lower the EI, the more pronounced the avoidance-oriented coping strategies (Table 5). Looking at which of the EI components were most strongly correlated with coping strategies, it is clear that the most moderate correlations (r > 0.4) were between EI traits and problem-focused coping strategies.

| Emotional intelligence subscales | General coping strategies | Problem-focused coping | Emotion-focused coping | Avoidant coping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General emotional intelligence | rho | 0.280 | 0.669 | 0.321 | -0.434 |

| p | 0.015* | <0.001* | 0.005* | <0.001* | |

| Well-being | rho | 0.286 | 0.544 | 0.322 | -0.384 |

| p | 0.013* | <0.001* | 0.005* | <0.001* | |

| Self-control | rho | 0.009 | 0.503 | 0.045 | -0.436 |

| p | 0.937 | <0.001* | 0.700 | <0.001* | |

| Emotionality | rho | 0.274 | 0.508 | 0.330 | -0.287 |

| p | 0.017* | <0.001* | 0.004* | 0.013* | |

| Sociability | rho | 0.395 | 0.523 | 0.436 | -0.237 |

| p | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.041* | |

| *p<0.05 | |||||

Table 5: Associations between emotional intelligence and coping strategies in mothers of adolescents with 1TDM .

Discussion

Type-1 diabetes is an incurable but manageable chronic disease. It often affects children and young people. The demands of the disease are incompatible with the child's psychosocial maturity and therefore require adult support, i.e. parental help. Emotional intelligence and coping strategies can play an important role in the management of 1TDM and the various challenges posed by the disease. Due to the lack of research in this area, it is not yet known exactly how emotional intelligence and coping strategies interact with the control of 1TDM. Thus, the present study aimed to assess the relationship between maternal emotional intelligence and coping strategies and diabetes management in adolescents with Type-1 diabetes [19].

The study revealed that the least expressed trait of emotional intelligence among mothers of children with 1TDM was sociability. This trait reflects the ability to build and maintain positive relationships with others, to communicate effectively and to cooperate in groups. This is very important in the context of 1TDM, as effective communication with both the child and the health care team can lead to better diabetes management outcomes. A study by Moore et al. [20] has observed an increase in family conflicts on the topic of 1TDM during adolescence, which is associated with poorer diabetes management. These conflicts may arise from a complex developmental period in which demands are difficult to reconcile with the demands of illness. Parents may experience difficulties during this period, which can lead to problems in maintaining a positive relationship and effective cooperation with the child. We can hypothesize that the lower expression of the trait of sociability in emotional intelligence may reflect and relate to the challenges and conflicts that arise during this difficult period.

In addition, the study also found that mothers whose child had optimal control of their illness had statistically significantly higher levels of sociability traits in emotional intelligence than mothers whose child had poor control. This means that mothers of a child with optimal diabetes management are better listeners, have a more pronounced ability to interact with different people and are able to have more effective interactions with others. It has been reported in various studies that it is conflicts touching the 1TDM that are associated with poorer diabetes management [20,21]. Ineffective communication and interaction with the child regarding the illness can lead to conflicts, which in turn can affect illness control. It is also essential that people with diabetes and their parents work and talk with their healthcare team to tailor the necessary treatment plan, including blood sugar monitoring, insulin use, etc. The results show that effective maternal interaction with those around them is important and necessary for optimal diabetes management.

The most expressed coping strategies were problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Avoidance-oriented coping was the least expressed. Research suggests that individuals with 1TDM are more likely to use problem-focused coping strategies rather than avoidance-focused coping strategies because they are more effective in managing diabetes-related stress [22]. Thus, it can be assumed that problem-focused and emotion-focused coping could also help mothers to manage diabetes-related stress more effectively, and ultimately to better manage 1TDM, improve their overall emotional health, and reduce the risk of complications in their children. In contrast, avoidance-focused coping may not address the underlying problem and may lead to increased maternal stress and negative health outcomes for the affected child.

The study revealed that coping strategies were not statistically significantly associated with diabetes management among mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes. Similarly, Jaser et al. [15] found a study involving mothers of children and adolescents (aged 8-15 years) with 1TDM. The study found no statistically significant association between coping strategies and diabetes management.

However, it is important to note that in this study, avoidance-focused coping was observed to be most strongly associated with poorer diabetes management compared to problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. A study by Mahfouz et al. [14] found that the more avoidance-focused coping strategies mothers use, the worse their children's HbA1c outcomes. In contrast, more adaptive coping strategies (e.g. planning and seeking emotional support) were associated with better HbA1c scores. This suggests that avoidance-oriented coping strategies may be more strongly associated with poorer diabetes management than other types of coping strategies.

The study found that emotional intelligence of parents of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes was statistically significantly related to coping strategies. Higher parental emotional intelligence was associated with problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, while lower emotional intelligence was associated with avoidance-focused coping. No other studies have examined the relationship between emotional intelligence and coping strategies in the context of 1TDM. However, existing research in other samples supports that higher EI increases the use of adaptive coping strategies [16].

Practical implications

Effective communication is necessary for optimal diabetes management. Ineffective communication and interaction with the child regarding the disease can lead to conflict. It is also essential that children and adolescents with diabetes and their parents work and talk with their healthcare team to tailor the necessary treatment plan, including blood sugar monitoring, insulin use, etc. The research results suggest that the development of the sociability trait of emotional intelligence could improve maternal functioning in a social context and act as a mediator for better control of the child's illness.

Limitations

The number of subjects in the study is small, with a larger sample size there is a chance that differences would become more apparent. In the study we can also observe that more of the children in the study had optimal diabetes management control than poor management. It can be assumed that the questionnaire was completed voluntarily by more motivated mothers, which may have influenced the results.

One of the limitations of this study could be the use of the EI self-assessment questionnaire. Research has shown a trend that EI self-assessment questionnaires show weaker associations with diabetes management [11]. We can therefore assume that this was the reason for the weaker ability to see and show the links between emotional intelligence and diabetes management. Self-assessment questionnaires reflect mothers' subjective views of their own emotional intelligence abilities. Devaux and Sassi [23] found in one of their studies that people are often biased in reporting their experiences in self-assessment questionnaires. Thus, we can assume that parents of a child with 1TDM may have been inclined to provide a more socially acceptable or desirable answer in this type of questionnaire. Respondents may also have been less able to assess themselves and their abilities. An audio-visual emotional intelligence test, or a similar psychometric emotional intelligence test, would have revealed less subjective indicators of the emotional intelligence of mothers of a child with 1TDM. In future studies, it would be important to include additional parts of the EI psychometric questionnaire that would provide a measure of the subjects' actual EI abilities, e.g. by asking them to recognise non-verbal reactions, to deal with complex emotional situations, etc. It would also be advisable to carry out a study of this kind over a longer period of time, routinely in the treatment setting, in order to obtain better insight and more objective results.

Finally, to determine the quality of disease management in 1TDM, HbA1c test results were requested. Recently, research has questioned the reliability of HbA1c alone in reflecting diabetes management [24]. In addition to HbA1c, it is important to assess other indicators of the quality of diabetes management, such as how often blood sugar is measured and the percentage of good glycaemia’s. Therefore, it would be important to include other quality indicators of diabetes management in future studies [25].

Conclusion

Mothers whose child had optimal diabetes management had more pronounced traits of sociability in emotional intelligence than mothers whose child had poor diabetes management

Coping strategies were not statistically significantly related to diabetes management among mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes.

Emotional intelligence was statistically significantly related to coping strategies in mothers of adolescents with Type-1 diabetes. Higher maternal emotional intelligence was associated with problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, whereas lower emotional intelligence was associated with avoidant coping.

References

- American Diabetes Association (2013). Standards of medical care in diabetes--2013.D Care 37: S14-S80.

- American Diabetes Association (2021) 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. D Care 44: S73-S84.

- Silina E (2022) Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and their parents. Nord J Psychiatry 75: S26-S26.

- Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, Bergenstal RM, DuBose SN, et al. (2015) T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. D care 38: 971-978.

- Svensson J, Sildorf SM, Breinegaard N, Lindkvist EB, Tolstrup JS, et al. (2018) Poor Metabolic Control in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes and Psychiatric Comorbidity. D Care 41: 2289-2296.

- Rumburg TM, Lord JH, Savin KL, Jaser SS (2017) Maternal diabetes distress is linked to maternal depressive symptoms and adolescents' glycemic control. Pediatric diabetes 18: 67-70.

- Capistrant BD, Friedemann-Sánchez G, Pendsey S (2019) Diabetes stigma, parent depressive symptoms and Type-1 diabetes glycemic control in India. Social Work in Health Care 58: 919-935.

- Petrides KV, Furnham A (2001) Trait emotional intelligence: psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies.

- Petrides KV, Sanchez-Ruiz MJ, Siegling AB, Saklofske DH, Mavroveli S (2018) Emotional intelligence as personality: measurement and role of trait emotional intellingence in educational contexts. Emotional Intelligence in Education: Integrating Research with Practice 49-81.

- Andrei F, Siegling AB, Aloe AM, Baldaro B, Petrides KV (2016) The Incremental Validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

- Zysberg L, Lang T, Zisberg A (2013) Parents' emotional intelligence and children's type I diabetes management. J Health Psychol 18: 1121-1128.

- Žilinskienė J, Šumskas L, Antinienė D (2021) Paediatric Type1 Diabetes Management and Mothers' Emotional Intelligence Interactions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18: 3117.

- Lazarus R, Folkman S (1984) Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. Springer publishing company.

- Mahfouz EM, Kamal N, Sameh E, Refaei SA (2018) Effects of mothers’ knowledge and coping strategies on the glycemic control of their diabetic children in Egypt. Int J Prev Med 9: 26.

- Jaser SS, Linsky R, Grey M. (2014). Coping and psychological distress in mothers of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Maternal and child health journal 18: 101-108.

- Sarabia-Cobo CM, Suárez SG, Menéndez Crispín EJ, Sarabia Cobo AB, Pérez V, et al. (2017) Emotional intelligence and coping styles: An intervention in geriatric nurses. Applied Nurs Res 35: 94-98.

- Ziasma HK, Kausar L, ZaibUn N, Batool F (2015) Emotional intelligence: a keyfactor for self esteem and neurotic behavior among adolescence of Karachi, Pakistan. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology 6.

- Carver CS (1997) You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief. Int J Behav Med 4: 92-100.

- Ye J, Yeung DY, Liu ES, Rochelle TL (2019) Sequential mediating effects of provided and received social support on trait emotional intelligence and subjective happiness: a longitudinal examination in Hong Kong Chinese university students. Int J Psychol 54: 478-486.

- Moore SM, Hackworth NJ, Hamilton VE, Northam EP, Cameron FJ (2013) Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: parental perceptions of child health and family functioning and their relationship to adolescent metabolic control. HRQOL 11: 1-8.

- Jaser SS, Patel N, Xu M, Tamborlane WV, Grey M (2017) Stress and coping predicts adjustment and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Ann Behav Med 51: 30-38.

- Hapunda G (2022) Coping strategies and their association with diabetes specific distress, depression and diabetes self-care among people living with diabetes in Zambia. BMC Endocr Disord 22: 215.

- Devaux M, Sassi F (2016). Social disparities in hazardous alcohol use: self-report bias may lead to incorrect estimates. Eur J Public Health 26: 129-134.

- Lundholm MD, Emanuele MA, Ashraf A, Nadeem S (2020) Applications and pitfalls of haemoglobin A1C and alternative methods of glycaemic monitoring. J Diabetes Its Complicat 34: 107585.

- International Diabetes Federation (2021) IDF Diabetes Atlas. Tenth Edition.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Zaleckytė D (2024) Associations of Maternal Emotional Intelligence and Coping Strategies with Diabetes Management in Adolescents with Type-1 Diabetes. J Comm Pub Health Nursing, 10: 519.

Copyright: © 2024 Zaleckytė D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1603

- [From(publication date): 0-2024 - Dec 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1290

- PDF downloads: 313