Association of Low Back and Pelvic Pain at the Second Trimester with that at the Third Trimester and Puerperium in Japanese Pregnant Women

Received: 05-Sep-2017 / Accepted Date: 05-Oct-2017 / Published Date: 12-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000351

Abstract

Introduction: Pregnant women at the second trimester have low back and pelvic pain (LBPP), although the second trimester in pregnancy is a stable stage. Studies on LBPP in pregnancy have mainly focused on late pregnancy and there have been few studies on LBPP at the second trimester. We carried out a prospective study to clarify the longitudinal changes in LBPP from the second trimester to one month postpartum and to determine the correlations of LBPP in those stages with factors associated with LBPP. Methods: We recruited 74 pregnant women who responded to questionnaires in all four stages (second and third trimesters and one week and one month postpartum). We designed a self-administered questionnaire including a visual analog scale (VAS) of LBPP and pregnancy mobility index (PMI). Results: The proportions of women who complained of LBPP were 71.6% at the second trimester, 79.7% at the third trimester, 70.3% at one week postpartum and 62.2% at one month postpartum. VAS score at the second trimester showed a significant positive correlation with VAS score at the third trimester. VAS score at the second trimester showed a significant positive correlation with VAS score at the third trimester (r=0.484, p<0.001). VAS scores showed significant positive correlations with PMI in all four stages. The proportions of women who had menstrual pain before pregnancy in women who had LBPP in all 4 stages and in any of the 4 stages were significantly higher than the proportion of women without LBPP in any of the stages. Conclusion: Forty percent of the women with LBPP at the second trimester had LBPP at one month postpartum, though the degree of LBPP was mild. Management of LBPP in pregnant women at the second trimester may be important. In health guidance for women in the second trimester, it is important for midwives to assess the pain in women with LBPP and to encourage self-care.

Keywords: Low back pain; Pelvic pain; Pregnancy; Prospective study

Introduction

The second trimester in pregnancy is a stable period when pregnant women can carry out daily life activities and work with few pregnancyrelated troubles compared to first trimester and third trimester. According to a study on discomforts in pregnant women in Japan, the mean numbers of discomforts per pregnant woman in the second and third trimesters were 45.4 and 48.7, respectively, suggesting that discomforts of pregnancy increase with advance of gestational stages [1]. Morning sickness-like syndrome occurs in the first trimester and low back and pelvic pain (LBPP) occurs with fetal growth in the second trimester. It has been reported that the proportions of pregnant women whose reporting 7 or more on a self-reported pain score by using a visual analogue scale (VAS) for low back pain were 21.5% at the second trimester and 68.2% at the third trimester. Addition it has been reported suggesting that intensity of low back pain increases with advance of gestational stages [2]. Mohammad et al., reported that mean VAS scores for low back pain at the second trimester and third trimester were significantly higher than that at the first trimester [3]. The second trimester is an important period in which LBPP as a minor pregnancyrelated trouble occurs since the constitution of a pregnant woman changes with fetal growth in the second trimester.

Studies on LBPP in pregnancy have mainly focused on women in late pregnancy, when the frequency of LBPP is high and there have been few studies focusing on the second trimester [4-7]. On the other hand, it has been reported that 11-43% of cases of LBPP in pregnancy continue to the postpartum period [8,9]. Coping with LBPP in the second trimester, which is a relatively stable stage, is important for reducing LBPP in the postpartum period. In addition, the studies for the relationship of LBPP from the second trimester to one month postpartum were few. The present prospective study was carried out to clarify longitudinal changes in LBPP at the second trimester, third trimester, one week postpartum and one month postpartum and to determine the correlations of LBPP in these stages with factors associated with LBPP.

Subjects and Methods

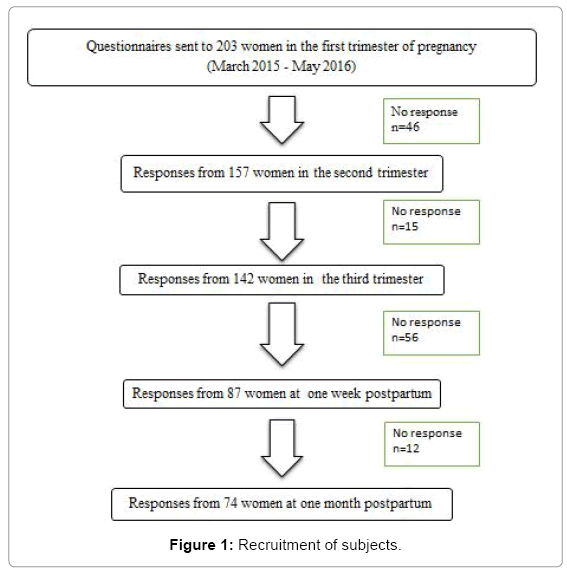

This study was conducted from March in 2015 to May in 2016 in a birth center in Kagawa Prefecture in Japan. The number of deliveries was approximately 500 per year in the hospital that we examined and sample size was determined by using permissible effect size, effect quantity, significance level and verification ability. We explained the aim of this study for 250 pregnant women at the first trimester and obtained the agreement from 203 pregnant women. We distributed questionnaires regarding LBPP to 203 pregnant women at the first trimester. Numbers of collected questionnaires were 157 in the second trimester (mean: 25.8 weeks, 24-30 weeks), 142 in the third trimester (mean: 35.7 weeks, 32-39 weeks), 87 in one-week postpartum and 74 in one-month postpartum. Seventy-four pregnant women who responded to questionnaires in all four stages were used as subjects for this study. We conducted a post hoc sample size test based on the VAS score average value and standard deviation in the second trimester and one month postpartum and actual power was 0.838. Participants were informed of the purposes and procedure of the study (Figure 1).

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Tokushima University Hospital (approval no. 2201).

Questionnaire

We designed a self-administered questionnaire consisting of three parts that took about 20 min to complete. The contents of the questionnaire in detail were shown in our previous report [10]. Briefly, the first part of the questionnaire consisted of questions regarding baseline characteristics such as age, marital status, education and week of pregnancy. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of questions regarding the presence of LBPP, location of pain and 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS) with end-points of no pain (0 cm) and worst thinkable pain (10 cm). We also asked about pregnancy mobility index (PMI) [11]. PMI has been developed to assess the ability to do normal household activities on a scale from ‘no problems performing this task’ to ‘performing this task is impossible or only possible with the aid of others’. PMI was shown to be a valid assessment of mobility during and after pregnancy [12].

Data Analyses

The changes in VAS score and PMI score during the four groups were evaluated by using the Friedman test. The VAS score and the PMI score at each stage were compared by Wilcoxon signed ranks test and their p values less than 0.0083 (0.05/6) were considered to be statistically significant. The correlation of a VAS score in each period with a VAS score in another period and the correlation of a VAS score with a PMI score was analyzed by using Spearman’s correlation. Background characteristics in the three groups (women who had LBPP in all stages, women who had LBPP in 1-3 stages of the 4 stages and women without LBPP in any stage) were evaluated by the Fisher’s exact test. We analyzed by using multivariate regression analysis among the three groups. The independent variables were working, parity, menstrual pain, presence of LBPP before pregnancy and past history of LBPP in the previous pregnancy. P values were two-tailed and those less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses for data evaluation were carried out using SPSS version 22 for Windows (IBM Crop., Aromonk, NY).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. Mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of the subjects was 32.4 ± 4.8 years. The subjects included 37.8% primiparous women and 62.2% multiparous women. 81% of women were working at the second trimester. The proportion of women with a past history of LBPP before pregnancy was 39.2% and for multipara, 56.5% women with a past history of LBPP in the previous pregnancy (Table 1).

| Age (years) | 32.4 ± 4.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 70 (94.6) |

| Not married | 4 (5.4) | |

| Working | Yes | 60 (81.1) |

| No | 14 (18.9) | |

| Smoking | Previous | 9 (12.2) |

| Never | 65 (87.8) | |

| Parity | Primiparous | 28 (37.8) |

| Multiparous | 46 (62.2) | |

| Menstrual pain | Yes | 51 (68.9) |

| No | 23 (31.1) | |

| Education level | High school | 19 (25.7) |

| Junior college or professional school | 31 (41.9) | |

| College or Graduate school | 24 (32.4) | |

| Presence of LBPP before pregnancy | Yes | 29 (39.2) |

| No | 45 (60.8) | |

| Past history of LBPP in previous pregnancy (n=46) | Yes | 26 (56.5) |

| No | 20 (43.5) |

*LBPP: Low Back and/or Pelvic Pain

*Ages are presented as means ± standard deviation. The proportions are shown in parenthesis

Table 1: Background characteristics of the subjects.

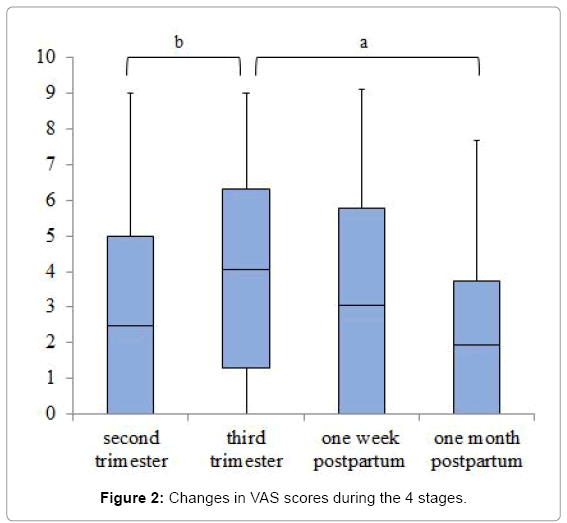

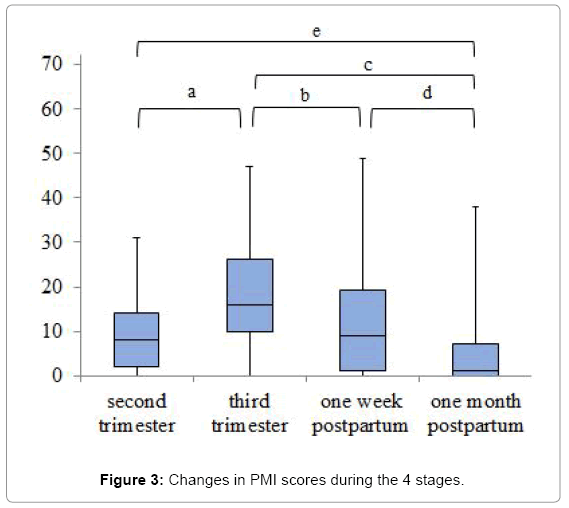

The proportions (numbers) of women who complained of LBPP were 71.6% (53 women) at the second trimester, 79.7% (59 women) at the third trimester, 70.3% (52 women) at one week postpartum and 62.2% (46 women) at one month postpartum. The median (range) of VAS scores were 2.5 (0.0-9.0) at the second trimester, 4.1 (0.0-9.0) at the third trimester, 3.1 (0.0-9.1) at one week postpartum and 1.9 (0.0-7.7) at 1 month postpartum. The median (range) of PMI scores were 8.0 (0.0-31.0) at the second trimester, 16.0 (0.0-47.0) at the third trimester, 9.1 (0.0-49.0) at one week postpartum and 1.0 (0.0-38.0) at one month postpartum. There were significant differences in VAS scores and PMI scores during the four stages (p<0.001). A comparison of the VAS scores for each stage showed a significant difference between the second trimester and the third trimester (p=0.006), the third trimester and one month postpartum (p<0.001). A comparison of the PMI scores for each stage showed a significant difference between the second trimester and the third trimester (p<0.001), the second trimester and one month postpartum (p<0.001), the third trimester and one week postpartum (p=0.007), the third trimester and one month postpartum (p<0.001), one week postpartum and one month postpartum (p<0.001). The VAS score at the second trimester showed a significant positive correlation with the VAS score at the third trimester (r=0.484, p<0.001). The correlation of VAS score at the second trimester with VAS score at one week postpartum was weak (r=0.253, p=0.030) and there was no correlation between VAS score at the second trimester and that at one month postpartum (r=0.172, p=0.142). VAS score at the third trimester was correlated with VAS scores at one week postpartum and one month postpartum (r=0.361, p=0.002 and r=0.323, p=0.005, respectively). VAS scores were significantly correlated with PMI scores at the second trimester (r=0.492, p<0.001), third trimester (r=0.570, p<0.001), one week postpartum (r=0.420, p<0.001) and one month postpartum (r=0.564, p<0.001). The PMI score at the second trimester showed a significant positive correlation with the PMI score at the third trimester (r=0.468, p<0.001), one week postpartum (r=0.499, p<0.001) and one month postpartum (r=0.380, p<0.001) (Figures 2 and 3).

As shown in Table 2, the status of LBPP was divided into 8 patterns according to the presence of LBPP at the 4 stages in pregnancy and postpartum. Fifty-three (60.8%) of the 74 women had LBPP at the second trimester. Thirty-one women (41.9%) had LBPP in all stages. The proportion of women who had LBPP at the second trimester, third trimester and one week postpartum was 12.2%. The proportion of women who had LBPP at the third trimester, one week postpartum and one month postpartum was 12.2%. Five women (6.8%) did not have LBPP in any of the four stages (Table 2).

| Second trimester | Third trimester | One week postpartum | One month postpartum | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 31 | 41.9 |

| No | 9 | 12.2 | |||

| No | No | 5 | 6.8 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 1.3 | |||

| No | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1.3 | |

| No | 2 | 2.7 | |||

| No | Yes | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| No | 3 | 4.1 | |||

| No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 | 12.2 |

| No | 2 | 2.7 | |||

| No | Yes | 1 | 1.3 | ||

| No | 3 | 4.1 | |||

| No | Yes | Yes | 1 | 1.3 | |

| No | No | 5 | 6.8 |

Table 2: Status of LBPP according to the presence of LBPP in the 4 stages.

We compared background characteristics in the three groups (women who had LBPP in all stages, women who had LBPP in 1-3 stages of the 4 stages and women without LBPP in any stage). The proportions of women with menstrual pain before pregnancy in women who had LBPP in all 4 stages and in any of the 4 stages were significantly higher than the proportion of women with menstrual pain before pregnancy in women without LBPP in any stage (p=0.003). LBPP in the three groups was associated with menstrual pain (β=-0.295, 95% CI: -0.676, -0.091, p=0.011) (Table 3).

| Women with LBPP | Women without LBPP | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All 4 stages | 1-3 stages of the 4 stages | n=5 | |||

| n=31 | n=38 | ||||

| Working | Yes | 25 (80.6) | 32 (84.2) | 3 (60.0) | 0.364 |

| No | 6 (19.4) | 6 (15.8) | 2 (40.0) | ||

| Parity | Primiparous | 10 (32.3) | 18 (47.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.091 |

| Multiparous | 21 (67.7) | 20 (52.6) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Menstrual pain | Yes | 24 (77.4) | 27 (71.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.003 |

| No | 7 (22.6) | 11 (28.9) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Presence of LBPP before pregnancy | Yes | 14 (45.2) | 15 (39.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.232 |

| No | 17 (54.8) | 23 (60.5) | 5 (100.0) | ||

| Past history of LBPP in previous pregnancy (n=46) | Yes | 15 (75.0) | 10 (47.6) | 1 (20.0) | 0.050 |

| No | 5 (25.0) | 11 (52.4) | 4 (80.0) | ||

*The proportions are shown in parenthesis

Table 3: Background characteristics of women with LBPP in all stages, women with LBPP in any of the 4 stages and women without LBPP in any of the stages.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we found that approximately 70% of the women had LBPP at the second trimester with a mean VAS score of 2.9 cm and that 5.4% of the women had a VAS score of more than 7 cm. It has been reported that the mean VAS score of lumbar pain in the second trimester was 5.6 cm in Iranian women [3]. It has been reported that the proportions of pregnant women whose reporting 7 or more on a self-reported pain score by using VAS for low back pain were 21.5% at the second trimester [2]. The degree of pain in women in the present study was mild, though 70% of the pregnant women complained of LBPP. It has been reported that the VAS score of cancer pain differed according to ethnicity and that the VAS score in Hispanic participants was significantly higher than that in Asian participants [13]. Avis et al., reported that bodily pain in SF-36 in Japanese women was lowest among African American, Hispanic, Chinese and Japanese in women transitioning through menopause [14]. Japanese women may have low sensitivity to pain.

In the prospective study from the second trimester to one month postpartum, we found that the proportion of women with LBPP peaked at the third trimester and decreased in the postpartum period. Also, VAS score at the third trimester was significantly higher than the second trimester and one month postpartum. These results are consistent with the results of previous studies. The lower back pain has been reported that the proportions of pregnant women whose reporting 7 or more on a self-reported pain score by using VAS for low back pain were 21.5% in the second trimester and 68.2% in the third trimester [2]. In a longitudinal study, Chang et al., found that the mean score of pain intensity did not show significant changes over time but that the mean score of pain interference showed a significant increase from 28 weeks to 36 weeks [15]. In a prospective study, Ostgaard et al., found that the VAS scores of back pain were 6 at 25 weeks of pregnancy, 3.5 at 11 weeks postpartum and 2.5 at 23 weeks postpartum, suggesting that the VAS score of back pain in the second trimester significantly decreases in the postpartum period [16]. Also, it has been reported that the prevalence of pelvic girdle pain (PGP) were 73% at 30 weeks of pregnancy, 48% in 0-6 weeks postpartum and 43% in 6-12 weeks postpartum [17].

The proportion of women with LBPP decreases in the postpartum period, but 40% of women with LBPP in the second trimester continue to have pain through the third trimester and one month postpartum. Also, it is necessary to examine the characteristics of cases that LBPP continued from second trimester to one week postpartum but not one month postpartum by an increase in the sample size. It has been reported that the proportions of women with lumbar pain, PGP and combined pain were 62% at 12 to 18 gestational weeks and 33% at 3 months postpartum [9]. Olsson et al., reported that the proportions of women with lumbopelvic pain were 44% at the second trimester and 38% at 6 months postpartum [18]. Robinson et al., reported that the proportions of women with PGP were 63% at 30 weeks of pregnancy, 31% at 12 weeks postpartum and 30% at one year postpartum [19]. Mogren reported that 43.1% of pregnant women complained of persistent pain at 6 months postpartum [8]. Pregnant women who complain of LBPP from the second trimester to one month postpartum may continue to have LBPP thereafter. In the present study, the proportion of women who had LBPP from second trimester to one month postpartum was 41.9% and the proportion of women who had LBPP from third trimester to one month postpartum was 12.2%. Thus, follow-up of LBPP from second trimester may be important. In addition, lumbar pain for a long time may cause difficulties in daily life and caring for children. Appropriate health guidance for LBPP by midwives is important in the second trimester. It has been reported that care managers help the patients to make lifestyle changes and provide the necessary information with monitoring their conditions in the management of patients with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and heart failure [20]. Thus, care managers may participate in the management for women with LBPP before pregnancy and lead to protective behavior.

Our results for correlations of VAS scores in periods of pregnancy and postpartum showed that women with severe LBPP at the second trimester had severe LBPP at the third trimester. The stronger LBPP in the second trimester was, the stronger was LBPP in the third trimester. It has also been reported that pain intensity at 24 weeks of gestation was a significant predictor of increase in pain intensity in the third trimester [15]. Pregnant women with moderate to severe LBPP at the second trimester need to cope with LBPP in order to reduce subsequent LBPP.

Our result regarding the change in PMI score during pregnancy was consistent with the result in the previous study [21]. Also, it has been reported that PMI score at 24 weeks of pregnancy can be a predictor of PMI score at 36 weeks of pregnancy [21]. Since the PMI score at the second trimester was correlated with the PMI scores at the third trimester, one week postpartum and one month postpartum in the present study, difficulty in daily life at the second trimester affect daily life thereafter. On the other hand, we showed that women with severe LBPP had disturbances in daily life since intensity of LBPP was associated with difficulties in daily life based on the result of a significant correlation of VAS with PMI. Severe LBPP causes a decrease in the quality of life at the second trimester, although the second trimester is a stable period for both the mother and fetus. Given that difficulty in daily life in the second trimester increases in the third trimester, efforts made to reduce the degree of difficulty in daily life in the second trimester should lead to a more comfortable daily life in the third trimester.

It has been reported that there was a significant correlation between higher VAS scores for pain intensity in women at 25 weeks of gestation and percent of women with persisting pain in postpartum for women with back pain and posterior pelvic pain [16]. Olsson et al. [18] found that there were no associations between the main variables they examined and postpartum lumbopelvic pain in the non-lumbopelvic pain group at 19-21 weeks of gestation in a prospective study through the second trimester and 6 months postpartum. In the lumbopelvic pain group at 19-21 weeks of gestation, the hazard ratios showed that those with a high degree of catastrophizing and more restricted physical ability had a more than twofold risk for lumbopelvic pain 6 months after delivery. Olsson et al. suggested that lumbar pain at the second trimester is a risk factor of lumbar pain at 6 months postpartum [18]. We showed that the correlation of VAS score in the second trimester with VAS score at one week postpartum was weak and that VAS score in the second trimester was not significantly correlated with VAS score at one month postpartum. The reason for this result is low VAS score in the second trimester in Japanese women. A prospective study from the second trimester to more than 3 months postpartum may be needed.

It has been reported that menstrual pain was a risk factor of lumbar pain in pregnancy and that past histories of lumbar pain before pregnancy and lumbar pain in the previous pregnancy were risk factors of lumbar pain in pregnant women [3,22,23]. We also previously showed that lumbar pain in the previous pregnancy was associated with lumbar pain in women in early pregnancy [10]. In the present study, we showed that the proportions of women with menstrual pain before pregnancy were high in women who had LBPP in all stages and in women who had LBPP in any of the stages in pregnancy. Given that lumbar pain at the second trimester may continue to one month postpartum, women with a past history of menstrual pain before pregnancy should be given an explanation at the second trimester about the possibility of long continuation of LBPP and should be encouraged to make efforts to care for the LBPP themselves.

Limitation

This study has several limitations. The sample size is relatively small and our results cannot be generalized. In particular, five of the women did not have LBPP in any stage. The characteristics of women without LBPP should be clarified by an increase in the sample size. The use of questionnaires is a limitation of this study. Our survey is a questionnaire survey collecting in one birth center and cannot be generalized. Objective assessments for pelvic pain such as active straight leg raise test and posterior pelvic pain provocation test may be needed.

Conclusion

Forty percent of the women with LBPP at the second trimester had LBPP at one month postpartum, though the degree of LBPP was mild. Management of LBPP in pregnant women at the second trimester may be important. In health guidance for women in the second trimester, it is important for midwives to assess the pain in women with LBPP and to encourage self-care.

Acknowledgement

- Shinkawa H, Shimada M, Hirokane K, Hayase M, Inui T (2012) Development of a scale for pregnancy-related discomforts. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 38: 316-323.

- Brown A, Johnston R (2013) Maternal experience of musculoskeletal pain during pregnancy and birth outcomes: Significance of lower back and pelvic pain. Midwifery 9: 1346-1351.

- Mohseni-Bandpei MA, Fakhri M, Ahmad-Shirvani M, Bagheri-Nessami M, Khalilian AR, et al. (2009) Low back pain in 1,100 Iranian pregnant women: Prevalence and risk factors. Spine J 9: 795-801.

- Albert HB, Godskesen M, Korsholm L, Westergaard JG (2006) Risk factors in developing pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 85: 539-544.

- Kovacs F, Garcia E, Royuela A, González L, Abraira V, et al. (2012) Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy. Spine 37: 1516-1533.

- Mota MJ, Cardoso M, Carvalho A, Marques A, Sá-Couto P, et al. (2015) Women's experiences of low back pain during pregnancy. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 28: 351-357.

- Owe K, Bjelland E, Stuge B, Orsini N, Eberhard-Gran M, et al. (2016) Exercise level before pregnancy and engaging in high-impact sports reduce the risk of pelvic girdle pain: A population-based cohort study of 39 184 women. Br J Sports Med 50: 817-822.

- Mogren IM (2006) BMI, pain and hyper-mobility are determinants of long-term outcome for women with low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Eur Spine J 15: 1093-1102.

- Gutke A, Ostgaard HC, Oberg B (2008) Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine 33: 386-393.

- Uemura Y, Yasui T, Horike K, Maeda K, Uemura H, et al. (2017) Factors related with low back pain and pelvic pain at the early stage of pregnancy in Japanese women. Int J Nurs Midwifery 9: 1-9.

- Van de Pol G, De-Leeuw JR, Van-Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, Heintz AP, et al. (2006) The Pregnancy Mobility Index: A mobility scale during and after pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 85: 786-791.

- Sabino J, Grauer JN (2008) Pregnancy and low back pain. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 1: 137-141.

- Im EO, Ho TH, Brown A, Chee W (2009) Acculturation and the cancer pain experience. J Transcult Nurs 20: 358-370.

- Avis NE, Colvin A (2007) Disentangling cultural issues in quality of life data. Menopause 14: 708-716.

- Chang HY, Lai YH, Jensen MP, Shun SC, Hsiao FH, et al. (2013) Factors associated with low back pain changes during the third trimester of pregnancy. J Adv Nurs 70: 1054-1064.

- Ostgaard HC, Roos-Hansson E, Zetherström G (1996) Regression of back and posterior pelvic pain after pregnancy. Spine 21: 2777-2780.

- Stomp-van den Berg SGM, Hendriksen IJM, Bruinvels DJ, Twisk JW, Van-Mechelen W, et al. (2012) Predictors for post-partum pelvic girdle pain in working women: The mom@work cohort study. Pain 153: 2370-2379.

- Olsson CB, Nilsson-Wikmar L, Grooten WJ (2012) Determinants for lumbopelvic pain 6 months postpartum. Disabil Rehabil 34: 416-422.

- Robinson HS, Vøllestad NK, Veierod MB (2014) Clinical course of pelvic girdle pain postpartum-impact of clinical findings in late pregnancy. Man Ther 19: 190-196.

- Ciccone MM, Aquilino A, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Sassara M, et al. (2010) Feasibility and effectiveness of a disease and care management model in the primary health care system for patients with heart failure and diabetes. Vasc Health Risk Manag 6:297-305.

- Bakker EC, van-Nimwegen-Matzinger CW, Voorden WEVD, Nijkamp MD, Völlink T (2013) Psychological determinants of pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 92: 797-803.

- Al-Sayegh NA, Salem M, Dashti LF, Al-Sharrah S, Kalakh S, et al. (2012) Pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain: Prevalence, risk factors and profile in Kuwait. Pain Med 13: 1081-1087.

- Terzi H, Terzi R, Alt?nbilek T (2015) Pregnancy-related lumbopelvic pain in early postpartum period and risk factors. Int J Res Med Sci 3: 1617-1621.

Citation: Uemura Y, Yasui T, Horike K, Maeda K, Uemura H, et al. (2017) Association of Low Back and Pelvic Pain at the Second Trimester with that at the Third Trimester and Puerperium in Japanese Pregnant Women. J Preg Child Health 4: 351. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000351

Copyright: © 2017 Uemura Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5862

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Oct 20, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4919

- PDF downloads: 943