Research Article Open Access

Assessment of Timing of First Antenatal Care Booking and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women who attend Antenatal Care at Health Facilities in Dilla town, Gedeo Zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region, Ethiopia, 2014

Teshome Abuka1*, Abebe Alemu2 and Balcha Birhanu31Dilla University College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Department of Public Health, Ethiopia

2Dilla University College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Department of Midwifery, Ethiopia

3Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences Nursing and Midwifery Department, Ethiopia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Teshome Abuka

Dilla University College of Health Sciences and Medicine, Department of Public Health

Tel: 254 22358143

E-mail: rom_tes@yahoo.com

Received Date: March 22, 2016; Accepted Date: May 30, 2016; Published Date: June 06, 2016

Citation: Abuka T, Alemu A, Birhanu B (2016) Assessment of Timing of First Antenatal Care Booking and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women who attend Antenatal Care at Health Facilities in Dilla town, Gedeo Zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region, Ethiopia, 2014. J Preg Child Health 3:258. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000258

Copyright: © 2016 Abuka T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Introduction: Yet in developing regions overall, only half of all pregnant women receive the minimum recommended number of antenatal visits four and lately timing of ANC booking. Objective: The main objective of this study was assessing timing of first ANC booking and associated factors among pregnant women in Dilla town, SNNPR, 2014. Methods: Facility based Cross-Sectional study design was conducted to assess the timing of first ANC booking and associated factors. Study subjects were selected using systematic random sampling. Data were entered onto a computer using Epi-info 3.5.1 statistical program then exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Logistic regression model was used to predict timing of first ANC booking and associated factors. Significance of association was declared if p value is < 0.05 and also OR was calculated to determine strength of association. Result: The study finding revealed that 35.4% respondents were booked first Antenatal care timely. The mean gestational age of timing of first ANC booking was 4 + 1.4 months. Binary logistic regression analysis revealed that respondents age(OR=0.2, 95% CI, 0.03-0.5, P=0.005), Education (OR=0.4, 95% CI, 0.2-0.9, P=0.04), Parity(OR=1.8, 95% CI, 1.1-3, P=0.01), knowledge on importance timely booking (OR=2, 95% CI, 1.3-3.3, P=0.003), those informed before to book ANC(OR=3, 95%CI, 1.1-9, P=0.03) and past ANC experience (OR=1.7, 95%CI, 1.1-2.8, P=0.022) were found as significant factors that influence timing of first Antenatal care booking. Conclusion and Recommendation: The findings of this study showed that 35.4% were booked timely. Thus, women’s educational status, knowledge of women on importance of timely booking, quality of ANC have to be considered when antenatal care programs are planned, implemented and evaluated to ensure timely booking of first ANC.

Keywords

Timing of first antenatal booking; Pregnancy; Antenatal care

Background

Pregnancy is one of the most important periods in the life of women, family and society. Antenatal care is one of the pillars of preventing adverse pregnancy outcome. The goal of ANC is to prevent health problems in both infant and mothers and also to ensure that each new-born has a good commencement [1]. In developing countries, particularly in most sub-Saharan Africa has high maternal morbidity and mortality, but ANC are initiated more likely at the second and third trimester. Timely initiation of ANC is important in the countries that have high maternal morbidity and mortality among reproductive age women to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality [2].

Antenatal care is more beneficial in preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes when it is received early in the pregnancy and continued through delivery. Early detection of problems in pregnancy leads to more timely referrals for women in high-risk categories or with complications where three-quarters of the population live in rural areas and where physical barriers pose a challenge to providing health care. Under normal condition, World Health Organization recommends that a woman without complications should have at least four antenatal care visits, the first of which should take place during the first trimester [1,3-5]. In Ethiopia, eleven per cent of women made their first ANC visit before the fourth month of pregnancy [4,5].

Literatures demonstrates that timing of first ANC has been affected by different associated factors like maternal education, parity, past experience of health service, knowledge and attitude towards pregnancy and its complication [6]. Older multiparous pregnant women are at particular risk of delaying antenatal care booking [7]. In contrast, antenatal care utilization is more common in younger women age 20-34 and which accounts around 36 per cent but, women age 35-49 received antenatal care utilization is 27 per cent [5]. Study that done in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi illustrated that pregnancy disclosure influenced timing of ANC adolescents and unmarried younger women secreted their pregnancies and delay ANC to avoid the potential social implications of pregnancy: exclusion from school, expulsion from their natal home, partner abandonment and stigmatization [7]. Unplanned pregnancy which means unmarried pregnancy is associated with late timing of ANC booking [8,9].

Women have triple roles burden which has direct link to ANC attendance. Thus, they often have an exhausting experience for women and the journey to health facilities represented a physical burden. Delays in ANC initiation are not however merely due to the associated indirect and direct costs [7]. A 75 per cent of women who received ANC are among those in the highest wealth quintile that is related to their level of occupation and on the other hand, 17 per cent among women in the lowest wealth quintile and those who have not good occupation [4]. Study done in Hadiya Zone, SNNPR, Ethiopia shows that there is direct association between women occupation and timing ANC booking and number of visits [8].

Mothers’ education level is significantly related to the receiving of the various components of antenatal care during pregnancy. In Indonesia, study indicated that 64 per cent of educated mothers are informed about signs of pregnancy complications but in contrast, 28 per cent mothers are not educated [10]. Study in Nigeria shown that late antenatal care booking is significantly influenced by the client's level of education [11].

Family economic status greatly influences the utilization of the health care service. It also direct link with timing of first antennal care booking and indicated as one of challenging factor for initiation of the ANC in some literatures. In Nigeria, 9.2 per cent of pregnant women could not attend antenatal care due to financial shortage. Attending ANC required direct or indirect costs [12-14]. According to EDHS 2011, a 75 per cent of women who received ANC are among those in the highest wealth quintile and on the other hand, 17 per cent among women in the lowest wealth quintile.

According to World Health Organization, at least four ANC visits are recommended for normal pregnancy (uncomplicated pregnancy). Of these four visits, the first visit is recommended to be carried out at first trimester (before four month of pregnancy). Despite of this assumption, the majority of pregnant women in developing countries including Ethiopia are booked late to ANC during their second and third trimesters. Therefore, this study would investigate first ANC booking and factors associated among pregnant mothers at dilla town, SNNPR, Ethiopia.

Conceptual Framework

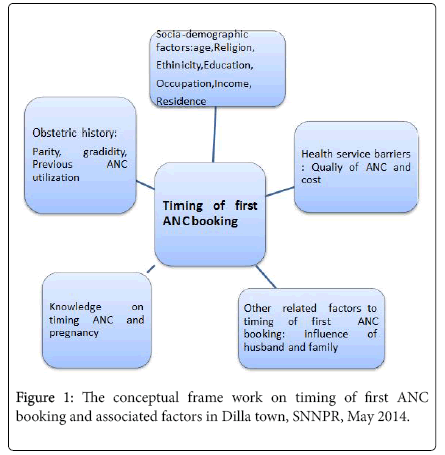

A Frame work was developed based on major research findings in the literatures that were associated with timing of first Antenatal care booking. Thus, the dependant variable and independent variables were conceptualized as follows (Figure 1):

Methodology

Study area

The study area was Dilla town in Gedeo Zone, SNNPR, and Ethiopia. It is located 356 km from Addis Ababa and 86 km from Hawassa. Reproductive age women (meaning age 15-49 years) are 19,136 (23.3% of Dilla town population). In Dilla town, there was one Hospital; two government health centers, private clinics and government and private pharmacies.

Study design and period

Institution based Cross-Sectional study was conducted among pregnant women who attended ANC at health facilities at Dilla town from April-May 2014.

Source of population

Source populations were all pregnant mothers living in Dilla town during study period.

Study population

The study populations were pregnant mothers visiting the health facilities during study period

Sample size determination

The actual sample size for the study was determined using formula for single population proportion by assuming 5% marginal error and 95% confidence interval(σ=0.05) and prevalence of the timing of first Antenatal care booking 40% or P=0.4 using the formula:

n=(Zα/2)2 P (1-p)/d2

n=(1.96)2 0.4 (0.6)/(0.05)2=369

Where:

n=the required Sample size

p=prevalence timing of first ANC booking (40 or P=0.4) (33).

Z=the value of the standard normal curve score corresponding to the given confidence interval 1.96

d=the permissible Margin of error (the required precision)=5%

By adding 10% of non-response rate, total of 406 pregnant women was recruited as study units among pregnant women who attended ANC follow up at health facilities in Dilla town during study period.

Sampling techniques

In this study, all health facilities that were providing ANC service in Dilla town (Dilla University Referral Hospital, Haroreso health Center (HC), Walamme HC, Dombosco Clinic, Selem Clinic and Fitsum Clinic) were included.

The sample size was distributed in proportion to average monthly load of previous year of pregnant women who made first ANC follow up at each health facility by using of formula population proportion sample (n/N × sample size).

Variables

Dependent variable

Timing of first visit of ANC booking.

Independent variables

Independent variables were socio-demographic characteristics (maternal age, Educational status, occupation, marital status, income, and residence), parity, past experience of ANC utilization, Knowledge and awareness on importance of timing of first ANC, attitude towards ANC service and husband involvement.

Data collection instrument

The standardized questionnaire was adopted Safe Motherhood Initiative and previously done research and then was translated in to Amharic by Language expert and back by another expert. Edited and finalized questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire contained questions on socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, timing of first ANC booking, past experiences services utilization and knowledge of women on importance of timing and pregnancy awareness.

Data collection

Training was given for data collectors (BSC Midwifes) concerning the research objective, data collection tools and procedures, and interview methods that were supposed to be applied during data collection. Trained data collectors were conducted data collection at health facility using revised version of data collection tool from April- May 2014. Data collectors were interviewed pregnant women waiting after they completed their daily visits.

Data quality assurance

To assure the quality of data, the questionnaire was pre-tested. Training was given for the data collector (BSC Midwifes) how to interview and check the questionnaires for completeness during collecting data. The facilitators and principal investigator were checked and reviewed the completeness of questionnaires and were offered necessary feedback to data collectors.

Data entry and analysis

After data collection, the questionnaire was checked for completeness and data entry was made by the principal investigator. The collected data was entered in to Epiinfo and translated Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20 for analysis. A logistic regression was used to identify the association of the independent variables on the dependent variable and then multivariate logistic regression was used to control cofounders and statistically significant associations in between variables. And also descriptive statistics was applied to describe mean and SD.

Ethical considerations

The study proposal was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Nursing and Midwifery Department, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University. Also authorization was obtained from Health Bureau of Dilla City Administration and Directors of all health facilities. The pregnant women were provided information by data collectors after they are asked for willingness and an informed verbal consent was obtained before data collection. The purpose of the study and significance of true information was given to the participants. Privacy and confidentiality was maintained throughout the data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation and result dissemination.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics of respondents

Majority of women involved in the study were age in between 21 and 34 years, 265 (68.3%). The mean ages of the respondents were 25.0+^5.3. Three hundred seventy nine (97.9%) mothers were married and one hundred sixty eight (43.4) mothers were house wives. The majority of respondents’ religion were Orthodox 158 (40.8%) followed by Muslim, Protestant, and Catholic (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years n=387 | Less than 20 years | 93 | 24 |

| 20-34 years | 265 | 68.5 | |

| 35 years and above | 29 | 7.5 | |

| Marital Status (n=387) | Single | 2 | 0.5 |

| Married | 379 | 97.9 | |

| Separate (Divorce, widowed) | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Religion (n= 387) | Orthodox | 158 | 40.8 |

| Muslim | 97 | 25.1 | |

| Protestant | 83 | 21.4 | |

| Catholic | 28 | 7.2 | |

| Others* | 21 | 5.4 | |

| Ethnicity (n=387) | Gedeo | 131 | 33.9 |

| Oromo | 56 | 14.5 | |

| Amhara | 73 | 18.9 | |

| Sidama | 48 | 12.4 | |

| Gurage | 57 | 14.7 | |

| Others ** | 22 | 5.7 | |

| Can’t read and write | 65 | 16.7 | |

| Education (n= 387) | Primary | 177 | 45.5 |

| Above Secondary school | 145 | 37.3 | |

| Occupation (n=387) | Employed | 93 | 24 |

| Merchant | 102 | 26.4 | |

| House wife | 168 | 43.4 | |

| Other*** | 24 | 6.2 | |

| < 500 ETB | 244 | 63 | |

| Family Income (n=387) | 501 -1000 ETB | 46 | 11.9 |

| >1000 ETB | 97 | 25.1 | |

| Residence (n=387) | Urban | 311 | 80.4 |

| Rural | 76 | 19.6 |

Table 1: Socio demographic characteristics of the respondents in Dilla town, SNNPR, May 2014.

Regarding educational status of respondents, Sixty five (16.7%) couldn’t read and write. One hundred Seventy Seven (45.5%) women were primary school education and one hundred forty five (37.3%) were secondary and above. Monthly family income of 244 (63.0%) respondents were 500 Birr and below, on the other hand 97 (25.1%) of respondents had monthly income of 1000 Birr and above. Three hundred eleven (80.4%) of study participants were from Dilla town and seven six (19.6%) were outside of Dilla town.

Obstetric history, Knowledge and practices of respondents on timing of first ANC booking

Among total respondents, One hundred sixty (41.3%) were with parity zero, while the rest of respondents two hundred twenty seven (58.7%) were parity one and above. Out of total respondents, One hundred thirty Eight (35.7%) reported that timely booking of first ANC was highly important for both mother and fetus. But, two hundred forty nine (64.3%) reported that they didn’t know the importance of the timely booking for mother as well as fetus.

Three hundred thirty (85.3%) of respondents were had information on Antenatal care booking, in contrast, fifty six (14.5%) were didn’t informed (advised) timing of ANC booking. Two hundred thirty one, (70%) out of those who had informed about ANC booking were got from health Professionals and the rest get informed from others source (family, friends, media) (Table 2).

| Variable | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does timely ANC booking important | Yes | 138 | 35.7 |

| No | 249 | 64.3 | |

| Is pregnancy Planned | Yes | 346 | 89.4 |

| No | 41 | 10.6 | |

| Pregnancy confirmed by | Urine test | 189 | 48.8 |

| Other methods | 198 | 51.2 | |

| Advised before to start ANC | Yes | 330 | 85.3 |

| No | 56 | 14.5 | |

| Who informed (advised) you to book ANC | Health professionals | 231 | 70 |

| Other (family, friends, media) | 99 | 30 | |

| Ever attendee ANC before (n=387) | Yes | 144 | 37.2 |

| No | 243 | 62.8 | |

| Waiting time affect ANC booking (n=387) | Yes | 93 | 24 |

| No | 294 | 76 | |

| Do you satisfied on ANC service (n=387) | Yes | 96 | 24.8 |

| No | 291 | 75.2 |

Table 2: Knowledge and practices of respondents on timing of First ANC booking in Dilla town, SNNPR, May 2014.

Out of the total respondents who had history of previous ANC, one hundred forty four (37.2%) reported that they have had experience of ANC service utilization prior to the current while the rest two hundred forty three (62.8%) did not have past ANC experiences.

Ninety three (24.0%) reported that the long waiting time in the health Institution affected the timing of first Antenatal care booking, but the majority of the respondents two hundred ninety four (76.0%) didn’t complain it as hindering factor for timing of the first ANC booking.

From the total respondents, two hundred ninety one (75%) women were didn’t satisfied on the quality of Antenatal care service provided (Client-Health Professionals Interaction, Privacy, respect of culture and service charge) during ANC follow up of previous and current pregnancy. In contrast, ninety six (24.8%) were satisfied on service provided.

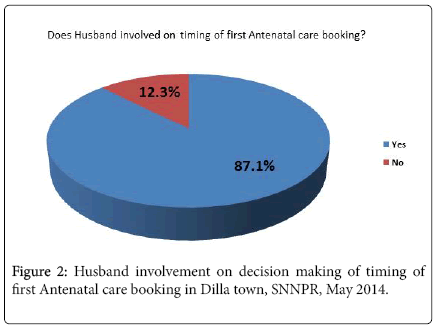

Husband involvement on decision making of timing of first ANC booking

The proportion of respondents 87.1% were made decision for booking with their partners (husbands) while forty eight (12.3%) didn’t made decision with their husbands (Figure 2).

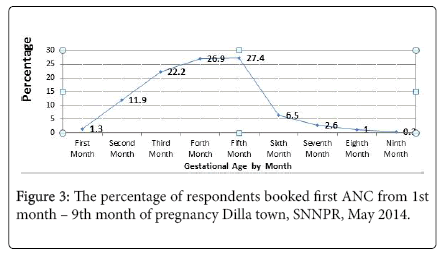

Timing of first ANC visit

Out of 387 respondents, one hundred thirty seven (35.4 %) were booked timely (before the fourth months pregnancy) while those two hundred fifty (64.4%) were booked within fourth month of pregnancy and above (lately). Booking of first ANC ranged from first month to ninth months of pregnancy (Figure 3). The mean gestational age the respondent booked was 4 months with standard Deviation of 1.4 months.

Association of respondent’s socio-demographic factors by timing of first ANC booking

Analyses of socio-demographic variable on binary logistic regression showed that respondents at 20th and early 30th were more likely to book timely as compared to the referents (OR=8.7, 95% CI, p=0.004). Also those who can’t read and write were less likely to initiate first ANC booking within recommend time as compared above secondary school educated (COR=0.2, 95% CI, 0.1-0.6, p=0.000). The respondents from urban area were more likely to start first ANC booking as compared those from rural area (COR=2.6, 95% CI, p=0.002).

Regarding family Income, those who had less than five hundred (500 ETB) per month were less likely to book first Antenatal care as compared to referents (OR=0.48, 95% CI, p<0.003). Employed respondents were more likely to initiate ANC timely as compared to referent (OR=2.8 CI=(1.0-7.5) P=0.035). On the other hand, the variables like marital status and religion did not show statistically significant association with timing of the first ANC booking (Table 3).

| Variable | Timely booked Number | Lately booked Number | Crude OR 95 % CI |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | < 20 years | 31 | 62 | 6.75(1.5-30) | 0.013 |

| 21 -34 years | 104 | 161 | 8.7(2.0-37) | 0.004 | |

| >35 years | 2 | 27 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 0 | 2 | - | 0.99 |

| Married | 135 | 244 | - | 0.99 | |

| Separate | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 55 | 103 | ||

| Muslim | 29 | 68 | |||

| Protestant | 31 | 52 | |||

| Catholic | 17 | 11 | 1 | 1 | |

| Education | Can’t read and write | 9 | 56 | 0.2(0.1-0.6)* | 0 |

| Level | Primary | 67 | 110 | 0.83(0.1-0.5) | 0.44 |

| Above Secondary School | 61 | 84 | 1 | ||

| Occupation | Employed | 50 | 43 | 2.8(1.0-7.5) | 0.035 |

| Merchant | 34 | 68 | 1.2 (1.3-4) | ||

| House wife | 46 | 122 | 0.9 (1.8 -5.2) | ||

| Others*** | 7 | 17 | 1 | ||

| Income per month | < 500ETB | 74 | 170 | 0.48(0.29-0.78) | 0.003 |

| 501-1000ETB | 17 | 29 | |||

| >1000 ETB | 46 | 51 | 1 | ||

| Residence | Urban | 122 | 189 | 2.6(1.4-4.8)* | 0.002 |

| Rural | 15 | 61 | 1 | ||

| Number of birth | Zero | 69 | 91 | 1.7(1.2-2.7)* | 0.008 |

| (Parity) | One and above | 68 | 159 | 1 | |

Table 3: Association of socio-demographic factors by timing of first ANC booking in Dilla town, SNNPR, May 2014.

Association of respondent’s knowledge and past ANC experience by timing of first ANC booking

Among the respondent those know the importance of timely booking were 2.9 times more to initiate first ANC booking as compared to referents (COR=2.9, 95% CI, 1.8-4.5, p<0.05) (Table 4).

| Variable | Timely booked Number | Lately Booked Number | Crude OR 95 % CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Does timely ANC booking important | Yes | 71 | 67 | 2.9(1.8-4.5)* | 0.002 |

| No | 66 | 183 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy planned | Yes | 131 | 215 | 3.6(1.5-8.7)* | 0.005 |

| No | 6 | 35 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy confirmed by | Urine test | 86 | 103 | 2.4(1.5-3.7)* | 0.001 |

| Other method | 51 | 147 | 1 | ||

| Informed to start ANC | Yes | 132 | 198 | 6.8(2.6-17)* | 0.005 |

| No | 5 | 51 | 1 | ||

| Attended ANC before | Yes | 67 | 77 | 0.4(0.3-0.7)* | 0.001 |

| No | 70 | 173 | 1 | ||

| Waiting time | Yes | 41 | 52 | 0.6(0.4-0.9)* | 0.045 |

| No | 96 | 198 | 1 | ||

| Satisfaction | Yes | 42 | 54 | 1 | |

| No | 95 | 196 | 0.6(0.3-0.9)* | 0.049 | |

| Does Husband involved timing | Yes | 127 | 212 | 1 | |

| No | 10 | 38 | 0.4(02-0.9)* | 0.027 |

Table 4: Association of socio-demographic factors by timing of first ANC booking in Dilla town, SNNPR, May 2014.

Out of respondents, those who with planned pregnancy were 3.6 times more book first ANC before four month of pregnancy as compared unplanned pregnancy (COR=3.6, 95% CI, 1.5-8.7, p<0.05).

The proportion of the respondents, those advised or informed before on booking of ANC were 6.8 times more to initiate ANC timely as compared referents (COR=6.8, 95% CI, 2.6-17, p<0.05) (Table 5).

| Variable | Timing of first ANC booking | Crude OR COR (CI) | Adj OR AOR (CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booked Timely Number (%) | Booked Lately Number (%) | |||||

| <20 Years | 31 (8) | 62(16) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Age | 21- 34 Years | 104(26.9) | 161(41.6) | 0.8(0.5-1.3) | 0.1(0.03- 0.6)* | 0.01 |

| >35 Years | 2(0.5) | 27(7) | 6.7(1.5-30)* | 0.2(0.03-0.5)* | 0.005 | |

| Education | Can’t read and write | 9(2.3) | 56(14.5) | 0.3(0.1-0.6)* | 0.4(0.2-0.9)* | 0.04 |

| level | Primary | 67(17.3) | 110(28.4) | 0.2(0.1-0.5)* | 1.1 (0.6-1.7) | |

| Above Secondary | 61(15.4) | 84(21.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Income per month | < 500ETB | 74(19.1) | 170(43.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| 501-1000ETB | 17(4.4) | 29(7.5) | 1.2(1.2-2.3)* | 1.8(1-3) | ||

| >1000 ETB | 46(11.9) | 51(13.2) | 2.4(1.5-3.9)* | 1.6(0.7-3.4) | ||

| Residence | Urban | 122(31.5) | 189(48.8) | 2.6(1.4-4.8)* | 1.6(0.8-3.2) | |

| Rural | 15(3.9) | 61(15.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Parity | Zero | 69(17.8) | 91(23.5) | 1.7(1.2-2.7)* | 1.8(1.1-3)* | 0.01 |

| One and above | 68(17.6) | 159(41.1) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Does timely ANC booking important | Yes | 71(18.2) | 67(17.3) | 2.9(1.8-4.5)* | 2 (1.3-3.3)* | 0.003 |

| No | 66(17.1) | 183(47.3) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy planned | Yes | 131(33.9) | 215(55.6) | 3.6(1.5 - 9)* | 1.3(0.5-3.5) | |

| No | 6(1.6) | 35 (9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Pregnancy confirmed by | Urine test | 86(22.2) | 103(26.6) | 2.4(1.5-3.7)* | 1.3(0.7-2) | |

| Other method | 51(13.2) | 147(38) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Informed to start ANC before | Yes | 132(34.2) | 198(51.3) | 6.8(2.6-17)* | 3(1.1-9)* | 0.03 |

| No | 5(1.5) | 51(13.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Attended ANC before | Yes | 67(17.3) | 77(19.9) | 0.4(0.3-0.7)* | 1.7(1.1 -2.8)* | 0.02 |

| No | 70(18.1) | 173(44.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Waiting time affect ANC | Yes | 41(10.6) | 52(13.4 | 0.6(0.4-0.9)* | 0.8(0.5-1.5) | |

| No | 96(24.8) | 198(51.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Satisfaction | Yes | 42(10.9) | 54(14) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 95(24.5) | 196(50.6) | 0.6(0.3-0.9)* | 0.6(0.4-1.2) | ||

| Husband involved | Yes | 127 (32.8) | 212 (54.8) | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 10 (2.6) | 38 (9.8) | 0.4(02-0.9) | 0.4(0.2-1.5) | ||

Table 5: Association of respondents’ knowledge by timing of first ANC booking in Dilla Town, SNNRP, May, 2014.

The respondents who had experience long waiting time for seeking service were less likely to initiate first Antenatal care booking before fourth month of pregnancy as compared to others (COR=0.6, 95% CI, 0.4-0.9, p<0.05).

The respondents who were not satisfied on service (Client- Professional interaction, privacy, respect, laboratory service, service charge) were less likely to book first Antenatal care timely as compared to referents (COR=0.6, 95% CI, 0.3-0.9, p<0.05).

Among respondents which partners (husbands) hadn’t participated on initiation of ANC were less likely to book first ANC with in recommended time as compared others and (COR=0.4, 95% CI, 02-0.9, p<0.05).

A multivariate analysis was done to identify independent predictors of timing of first Antenatal care booking. As result, analysis revealed that respondents Age, education, parity, knowledge on timely booking and advised to book before were shown significant association with timing of first ANC booking even after controlling for confounding factors.

The study finding reveals that respondents age 35 and above were less likely to book timely as compared referents (AOR=0.2, 95% CI, 0.03-0.5, p<0.05) and Also respondents who can’t read and write were less likely to book first ANC within recommended time as compared others (AOR=0.4, 95% CI, 0.2-0.9, p<0.05). Analysis showed that respondents with parity zero were 1.8 times more to book first Antenatal care timely as compared respondents those who had parity one and above (AOR=1.8, 95% CI, 1.1-2.8, p<0.05). Analysis revealed that respondents those know the importance of timely booking were two times more to book first Antenatal care within recommended time as compared to referents (AOR=2.1, 95% CI, 1.3-3.4, p<0.05). The proportion of respondents who advised (informed) before to book ANC were three times more to book first ANC within recommended time compared to others (AOR=3.0, 95% CI, 1.2-10, p<0.05 ). The proportion of respondents those didn’t have experience of past Antenatal care service utilization were 1.7 times more to book first ANC timely when compared to the referents (AOR=1.7, 95% CI, 1.1-2.8, p<0.05).

Discussion

This facility based cross sectional study endeavoured to assess the timing of first Antenatal care booking and associated factors with timing. The findings of this study revealed that 35.4 % were booked timely while 64.4% were booked lately (within fourth month of pregnancy and above). Booking of first Antenatal care ranges from first month to ninth months of pregnancy. The mean gestational age the respondent booked was 4 months with standard Deviation of 1.4 months

According to this study finding, booking first ANC timely is lower when compared to study shown in Nigeria at higher health facilities (46.7%) and in Addis Ababa health facilities (40.2%) (16,33) respectively. In contrast, finding of this study is higher when compared study done in Tanzania on women who attended ANC shown (29%) of women booked before four month of pregnancy [15,16] and only 17 per cent of women initiated booking of first Antennal care with first trimester in Uganda [17].

This finding is higher when compared to EDHS 2011, which only 11% women booked timely [5]. This inconsistency could be attributed to the fact that EDHS covered more remote areas where health institution could be a major predictor of ANC utilization. It is also significant to note down the time gap between the EDHS and this study.

By multivariate analysis, this study revealed there is statistically significant association in between maternal age and timing of first ANC booking within recommended time (AOR=0.2, 95% CI, 0.03-0.5, p<0.05). This finding is similar with some Literatures shown maternal age was found as factor of booking of first ANC [8,10]. But in contrast, EDHS 2011, that indicated as maternal age and ANC utilization has no significant association [5]. This inconsistence of findings might be due to difference socio-demographic characteristics of the study population and time gap of studies. In this study, multivariate analysis revealed that women education has statistically significant association with timing of first ANC booking. Those women with no education were much less likely to book within recommended time as compared educated one(AOR=0.4, 95% CI, 0.2-0.9, p<0.05. This finding is similar with the Study finding in Nigeria and in Metekel Zone, North West, Ethiopia that shown level of education significantly associated with timing of first ANC booking [11] respectively.

According to EDHS 2011, 91 per cent of women with more than secondary Education received ANC as compared with 25 per cent of women with no Education [5]. The possible justification for educated women’s to book first ANC within recommended time could be the higher the educational status the better understanding of information and the better the knowledge about the importance of timely booking of first ANC.

Multivariate analysis in this study, parity was found as statistically significant factor influence timing of first Antenatal care. Respondents with parity Zero were 1.8 times more booked within the recommended as compared with that of women with parity one and above (AOR=1.8, 95% CI, 1.1-2.8, p<0.05). Similarly, in Nigeria, 53.3 per cent women were booked lately as parity increases and also in Indonesia 16% [10,11] respectively. This finding is consistent with EDHS 2011, women with high parity less likely to time first ANC booking before four month of pregnancy.

In this study, multivariate analysis revealed that past experience of ANC service utilization has significant association with timing of first ANC booking. The proportion of respondents those didn’t have experience of past Antenatal care service utilization were 1.7 times more to book first ANC timely when compared to the referents (AOR=1.7, 95% CI, 1.1-2.8, p<0.05). Similarly, other study revealed that quality of previous service and satisfaction influence booking [16] and 28.7 per cent of women complained long waiting time as hindering factors for booking of first ANC timely [17]. In this study, finding was more or less similar that 24 per cent of women reported that long waiting time as factor not to book timely.

Also study in Hadiya Zone, revealed that waiting time to get service has significant association with booking of first ANC [8]. By multivariate analysis, this study revealed that woman’s’ knowledge on importance of the timely booking has significant association with timing of first ANC booking within recommended time as compared to referents.

Analysis revealed that respondents those know the importance of timely booking were two times more to book first Antenatal care within recommended time as compared to referents (AOR=2.1, 95% CI, 1.3-3.4, p<0.05). In the same manner, study shown that 74 per cent of women who lacked sufficient knowledge on the importance of booking timely were booked first ANC lately as compared to others [17]. Study shown that 22.8 per cent women were booked lately due lack of knowledge on importance of timely booking [11]. Knowledge of mothers on importance of timely booking was strong predictor of timing of first ANC booking before fourth month of pregnancy as recommended [8,17].

Conclusion

Out total respondents 35.4 per cent made their first ANC booking before fourth month’s pregnancy whereas 64.4 per cent were booked within fourth month of pregnancy and above.

Among respondents socio-demographic characteristics, age was found as independent determinant factor of timing of first Antenatal care booking. Respondents’ education was found to affect timing of first ANC booking. Knowledge of respondents on importance of timely booking ANC for the health of mother and fetus were found low. Respondents’ knowledge on importance of timely booking was revealed as significant factor of timing first ANC booking. Parity of respondents was indicated as one of factors that significantly associated with timing of first Antenatal care booking. Respondents awareness (being advised or informed) on timing of first Antenatal care booking was found as statistical significant factor for timing of first Antenatal care booking

Pervious ANC utilization was a negative forecaster for timing of first Antenatal care booking. Therefore, only 35.4 per cent of respondents were booked with in recommended time. The respondents Age, educational status, parity, knowledge on importance timely booking, awareness (being informed before to book) and past experience of Antenatal care service utilization was significantly associated with timing of first Antenatal care booking.

Recommendation

Based on the findings of this study the following recommendations were made:

• Dilla town, Health office, should develop a detailed and clear guideline and structure that will advance knowledge of reproductive age women on timing of Antenatal care.

• HEW should provide clear information on booking ANC to the expectant mother should be established.

• Training on simple and effective way of providing ANC should be given to health care providers.

• All stack holder should focus on advancement of women Education

• Dilla City Administration should emphasis ever more on knowledge of women on timing and quality of ANC service when programs are planned, implemented and evaluated.

There should be further quantitative and qualitative studies focusing on quality of ANC service.

References

- Banta D (2003) what is the efficacy/effectiveness of antenatal are and the financial and organizational implications? Copenhagen: WHO Regional office for Europe.

- Carla A, Tessa W, Blanc A, Van P (2003) ANC in developing countries, promises, achievements, and missed opportunities; an analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990-2001.

- United Nation Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon (2012) Millennium Development Goals Report.

- Central statistical Authority and ORC Macro CSA 2005. EDHS. Addis AbabaCalverton, Maryland, USA.

- Simkhada B, Teijlingen E, Porter M, Simkhada P (2008) Factors affecting the Utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: Systematic review of the literature. J AdvNurs 619: 244-260.

- Pell C, Menaca A, Were F, Afrah N, Chatio S, et al. (2013) Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: Results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PLoS ONE 8: 1.

- Zeine A (2010). Factors influencing antenatal care service utilization in Hadiya Zone. Ethiop JHealth Sci2: 2.

- BoerleiderF (2013) Factors affecting the use of prenatal care by non-western women in industrialized western countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13: 81.

- (2013) Statistics Indonesia (BadanPusatStatistik-BPS) National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN) and KementerianKesehatan and ICF International.

- Dennis I, Bernard U (2012) Gestational age at booking for antenatal care in a tertiary health facility in North-Central, Nigeria. Niger Med J 53: 236-239.

- Gross J (2012) Timing of antenatal care for adolescent and adult pregnant women in South-Eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12: 16.

- Exavery N (2013) How mistimed and unwanted pregnancies affect timing of antenatal care initiation in three districts in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13:35.

- Kyei N, Campbell O, Gabrysch S (2012) The influence of distance and level of service provision on antenatal care use in rural Zambia. PLoS ONE 7: 10.

- Ochako (2011) Utilization of maternal health services among young women in Kenya: Insights from the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, 2003. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 11: 1.

- Yang Y (2010) Factorsaffectingtheutilization ofantenatalcareservices AmongwomeninKhamDistrict, XiengkhouangProvince,LaoPDR. Nagoya J Med Sci 72.

- Ijeoma S, Vivian B (2012) They told me to come back: Women’s antenatal care booking experience in inner-city Johannesburg. Matern Chill Health J 17: 359-367.

- EPN, IGO (2010) Reasons given by pregnant women for late initiation of antenatal care in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Ghana Med p: 44.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14410

- [From(publication date):

June-2016 - Apr 05, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12869

- PDF downloads : 1541