Assessment of Attitude of Parents toward Childrens Mental Disorder and its Relation with Parents Helps Seeking Behaviors

Received: 31-Aug-2018 / Editor assigned: 01-Jan-1970 / Reviewed: 01-Jan-1970 / Revised: 01-Jan-1970 / Accepted Date: 04-Feb-2019 / Published Date: 11-Feb-2019

Abstract

Background: The purpose the study was to assess parent’s attitudes toward mental illness in children and is relationship with help seeking behaviours.

Method: This cross-sectional study was conducted in a pediatric psychiatric clinic of under affiliation of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2016-17. All children’s parents or guardians who referred for the first time to the clinics were the study population. Convenient Sampling was applied and 400 subjects were included by survey method. The data collection tool for this study included a form for demographic data, a questionnaire for assessing parents’ attitude toward the causes, behavioral demonstrations and treatment of mental disorders in children, and finally a checklist to determine help seeking behaviors. Descriptive and inferential statistics was applied with SPSS software version 16 for data analysis.

Results: 93.7% of parents had a good attitude toward mental illness in the three studied realms. 56.25% of parents referred to official sources of help. The results of this research showed that there was a significant difference between the mean scores of parents’ attitude (sum of the three areas) in terms of child’s gender, parents’ marital status, father’s job, father’s education, and mother’s education and there was a significant relationship between help seeking behavior of parents just with fathers’ education level (P<0.05).

Conclusion: The results showed that parents had a good attitude toward their children’s mental disorders However, it should not be overlooked that nearly half of parents were still referring to unofficial sources of assistance.

Keywords: Help seeking; Mental disorder; Attitude; Children

Introduction

According to statistical data reported by the World Health Organization, nearly one-third of the world’s populations express some problems in their lifetime which are clinically identified as mental disorders. Moreover, according to the WHO’s 2003 report on mental health in Europe, one out of every five people in Europe had been suffering from periods of depression. Because of the growing trend of mental disorders, it is shown that more than 30% of patients admitted to general practitioners are people who suffer from mental health problems [1]. In a study which was conducted in 2005 in 16 European countries it was found that 27% of European adults had been affected by at least one mental disorder for a 12-month period [2]. According to the World Health Organization in 2009, 26.6% of people over 18 years in America, with a population of nearly 57.7 million people, are suffering from diagnosed mental disorders. In addition, mental disorders are the most common cause of disability between the ages of 15-45 in America and Canada; Based on DALY scale, disability caused by mental disorders are among the most common types of disability [3]. The results of an international study, which evaluated the relationship between mental disorders and public health and disabilities due to mental illnesses, it was found that more than half of cases of disability in people aged 10 to 24 years old were due to neurological and psychological conditions such as substance abuse or self-destructive behaviors [4].

More than half a century ago, in 1960s, Nunnally [5] in his study showed that there were a very little knowledge about mental illnesses in the community, and word psychopath is always associated with a feeling of fear, mistrust, and hatred. Such a stigmatizing view still deeply exists in many communities. Many of other studies on the attitudes and opinions of the public about mental illness, from the late 1950s to the present day, have reported similar results [6-8]. According to the results of some studies by the American Mental Health Association (2008), 52% of the people were uncomfortable to be near a person who committed suicide, 55% avoided being with schizophrenic patients and people with bipolar disorder, and 77% did not feel good to be with a teacher or partner with emotional disorders or schizophrenia. Such attitudes are significantly different from people’s attitudes toward physical illnesses, for example, 98% of participants had no problem with having a friend with diabetes or cancer, and 93% were comfortable to work with a colleague or manager who was suffering from these diseases [9].

In the studies which have been conducted on public attitudes about mental illnesses, from the beginning of 1990s to the present, there are four common critical points. First, a lot of people cannot correctly identify mental disorders. Second, people’s beliefs about the causes of mental disorders and effective treatment for various mental problems are very different from the views of mental health specialists. Third, mental illnesses especially schizophrenia are considered as a great shame and stigma for those who suffer from the disease. Fourth, most studies which evaluated the effects of social and demographic variables on people’s beliefs about patients with mental illness it has been shown that the elderly, people with low education, and those with little knowledge of mental disorders are less tolerant in their contacts with such patients [10-14].

In the past, many studies were conducted on the psychological problems of children based on adult psychiatry and consequently by which many adults were labeled and stigmatized. However, recent studies have shown that children are far more vulnerable to stigmatization and the mental health problems of children need more professional diagnosis and treatment, far more than adults [15]. Emotional and behavioral disorders among children and adolescents are increasingly getting more prevalent. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, one out of every ten children and adolescents is faced with mental health problems, but of those with the problems, only 20% receive adequate treatment [15,16]. Of course, in case of providing appropriate intervention and treatment, several problems such as substance abuse, educational problems, legal disputes, and ultimately suicide can be reduced [17,18].

Nowadays, it is recognized that there is a gap between the need for and the use of services which is called service gap. Such a gap is present in mental health problems [19] and it has reduced the tendency of people to get help from others and pay for the mental health services [20]. When the person in need is a child, his or her parents must provide and take advantage of such health care services. Previous studies indicate parents’ negative attitude toward help seeking medical services is one of the potential obstacles in receiving psychiatric services for children. Nevertheless, there are some other external factors that affect the utilization of services for children, such as the high costs of care, social stigmatization against mental illness, and the availability of services [21-23]. Studies show that parents take their children to a psychologist or psychiatrist only when they feel helpless and when they have already tried many ways they knew and have become assured about their methods’ lack of efficiency [24-27].

A study in 2000 showed that 30% of parents in America, with the emergence of the early signs of mental disorders in their children, referred to a psychologist for consult and 11% of parents referred to a psychiatrist for drug intervention. In other words, 59% of children with primary symptoms of emotional disorders did not receive any intervention and they were deprived of receiving any services up to a point when they had shown moderate to severe symptoms of mental illness. In addition, the survey also showed that families who had children at higher risk of emotional disorders did not refer and ask for treatment earlier than other families [27]. Moreover, the results of a study in Australia showed that from a total of 11000 students aged 16- 24 years old, only 32% of young people who had experienced very high levels of anxiety or depression benefited from mental health services. As estimated by the Australian National Mental Health Organization only 25% of children aged 4-17 years old with known psychiatric disorders are receiving appropriate mental health services. It was also found that children with depression are more at risk of stigmatization than adults and they are far more in need of immediate official diagnosis and treatment of their problems than adults [28]. About 20% of children and adolescents are facing with the minimum amount of mental health problems, and almost 10% of them are suffering from moderate to severe disorders that require intervention. It is assumed that cultural factors have a significant impact on the use of these services for several reasons. One of the main reasons is the role and impact of culture on attitudes toward seeking help for mental health issues; as a result, it is necessary to conduct and support further researches on the attitudes of parents and community members about seeking help for psychological issues [29].

Eiraldi et al. [30] found that labeling and stigmatization of mental health services likely had an impact on parents’ decision to use the services, especially in families that had a little knowledge about the science of psychopathology and treatment methods.

The abovementioned items show that the attitudes of a patient or his / her family is one of the most important factors for predicting adults’ help seeking behaviors. Even in developed countries, there is not correct knowledge and attitude towards mental illness. However, in a country like Iran which is a developing country and most of its population have strong religious beliefs, so far there has been no study on people’s attitude toward help seeking behavior for mental illnesses. It should be noted that the Ministry of Health’s Department of Health announced that 20% of children and adolescents are faced with mental disorders to some extent, while 32% have mood disorders, and 50% are violent and aggressive. Furthermore, anxiety is prevalent among 37% of children and adolescents [31]. Needless to say, if parents do not receive assistance from official sources, its irreparable consequences for these children will be inevitable in the future. It indicates a critical need for studies on mental illnesses in children and their required services. Thus, this study was aimed to assess parent’s attitudes toward mental illness in children and is relationship with help seeking behaviors.

Material And Methods

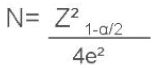

This cross sectional study was conducted in child psychiatry clinics affiliated to Tehran University of medical sciences (Roozbeh Hospital and Hazrat Ali Asghar Hospital) in 2016 and 2017. The subjects of this study were parents or family members of children who for the first time attended child psychiatry clinics or were referred by schools and health counseling or centers to have their children visited and examined for behavioral problems. None of the subjects referred to these centers before. Due to the lack of access to a similar study in Iran, using the following formula and considering a ratio of 50%, P=0.5 (the proportion of parents with good attitudes), α=0.05 (confidence interval of 95%) and e=0.05, the sample size was determined as 384 people.

Taking into consideration the possible loss of some of the samples, the sample size was changed into 400 people and 400 eligible parents or family members were enrolled in the study. In this study, we used convenience sampling method; accordingly, all the parents and family members who referred to the mentioned centers during the period of the study and consented to participate in the study received a questionnaire and were asked to complete the questionnaire.

The data collection tool for this study included a form for demographic data, a questionnaire for assessing parents’ attitude toward the causes, behavioral demonstrations, and method of treatment of mental disorders in children, and finally a checklist to determine help seeking behaviors. The form of demographic data included demographic variables (age of parent and child, gender of parent and child, occupation &education of parents, economic level of family, marital status, and number of children). The economic level of family was based on self-reported.

To assess parents’ attitudes, first based on literature review and similar instruments an initial draft was prepared which was about three factors of knowledge, emotion, and action. Then, to prove the scientific validity of the questionnaire, its content validity was tested. For that reason, the designed questionnaire was presented to 12 professors and experts in Roozbeh hospital and school of nursing and midwifery in Tehran University of medical sciences, and their comments were used to revise and improve the questionnaire. In order to test the face validity of the questionnaire, it was distributed among 10 parents who were met the inclusion criteria and they were asked to complete the questionnaire (the data collected from their answers were not included in the analysis of main sample size, however after completing the questionnaire, they were interviewed individually for 10-15 minutes and they were asked about their attitudes, thoughts, and feelings about the questionnaire and its possible problems).

To assess the reliability of the questionnaire was completed within 15 days by 10 parents in two stages. The correlation coefficient between two stages of the first area (attitude toward the causes of mental disorders in children) was 0.89, in second area (attitude toward the behavioral demonstrations of mental disorders in children) was 0.87 and in third area (attitudes toward treatment methods of mental disorders in children) was 0.92.

The comments were utilized under the guidance of professors and advisors. Thus, the final questionnaire includes 61 questions designed in three sections (18 questions about parents’ attitudes toward causes, 25 questions about behavioral demonstrations, and 18 questions about methods of treating mental illnesses in children). The questionnaire was scored based on Likert scale and ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The answer to each question received a score between 0 and 4. Attitude in every area was divided into four parts: poor, average, good, and excellent.

In the first area (attitude toward the causes of mental disorders in children) and the third area (attitudes toward treatment methods of mental disorders in children): a score between 0-18 represented poor attitude, between 18-36 represented average attitude, between 36-54 represented a good attitude, and between 54-72 represented a great attitude of parents.

In the second area (attitudes toward behavioral demonstrations of mental disorders in children): a score between 0-25 represented poor attitude, between 25-50 represented average attitude, between 50-75 represented a good attitude, and between 75-100 represented a great attitude of parents.

Parents’ help seeking behavior was also examined by the checklist. The checklist investigated the behaviors of parents before referring to the medical center; referring to unofficial sources (relatives and close friends, mass media, and relying on traditional treatments, spiritual methods, life forecasters, and exorcism) received a zero point, and referring to official sources (psychiatrist, general practitioner, consultant, neurologist, and psychologist) received one point. To analyze the data via descriptive statistics, tables and indexes of frequency of distribution were used. Statistical analysis was used to examine the relationship between attitudes and the variables of interest; hence we used Pearson correlation coefficient, x² test, T test, and ANOVA.

To observe the ethics of research, first it was approved by the ethics committee and received written permission from the authorities of university and hospitals; second, the subjects were informed that they were free to participate in the research; in addition, informed written consent was obtained from the subjects to participate in the study and complete the questionnaire.

Results

The results indicated that most of people who referred to the clinics (70.25%) were mothers of children with mental disorders. Most children (45.5%) were in the age group 5-11 years. Most parents (48.8%) were aged between 30 to 40 years old, and most of them (69.8%) referred to treatment centers to seek help for the mental health problems of their sons. Most children (57.5%) were the first child in their family and the majority of families (91.5%) had three children or less. Most parents who participated in this study (87.5%) were living with his / her spouse and a child or children. The majority of them (72.2%) reported their household economic status to be moderate; fathers were mostly self-employed (44%), and mothers were mostly housewives (77.8%). Concerning education level, many of fathers and mothers who were surveyed in this study (52.8% and 87.5%, respectively) were high school diploma (Table 1).

| Parent gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 117(29.20) | 67(29.77) | 50(28.57) |

| Female | 283(70.75) | 158(70.23) | 125(71.43) |

| Child gender | |||

| Male | 279(69.8) | 159(70.7) | 120(68.6) |

| Female | 121(30.2) | 66(29.3) | 55(31.4) |

| Parent age M (SD) | 37.49(7.12) | 37.24(6.7) | 37.83(7.6) |

| Child age M (SD) | 9.84(3.79) | 9.66(3.7) | 10.07(3.8) |

| Number of child | |||

| <=3 | 366(91.5) | 271(93.8) | 155(88.6) |

| >3 | 34(8.5) | 14(6.2) | 20(11.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 350(87.5) | 204(90.7) | 146(83.4) |

| Divorced | 24(6.0) | 9(4.0) | 15(8.6) |

| Remarried | 14(3.5) | 6(2.7) | 8(4.6) |

| Widowed | 12(3.0) | 6(2.7) | 6(3.4) |

| Economic level | |||

| high | 29(7.3) | 14(6.2) | 15(8.6) |

| Moderate | 289(72.2) | 169(75.1) | 120(68.6) |

| Low | 82(20.5) | 42(18.7) | 40(22.9) |

| Father job | |||

| worker | 82(20.5) | 45(20.0) | 37(21.1) |

| government employee | 119(29.8) | 73(32.4) | 46(26.3) |

| Self-employment | 176(44.0) | 94(41.8) | 82(46.9) |

| Retired | 20(5.0) | 12(5.3) | 8(4.0) |

| Unemployed | 3(0.8) | 1(0.4) | 2(1.1) |

| Mother job | |||

| worker | 15(3.8) | 8(3.6) | 7(4.0) |

| government employee | 40(10.0) | 23(10.2) | 17(9.7) |

| Self-employment | 23(5.8) | 14(6.2) | 9(5.1) |

| Retired | 11(2.8) | 4(1.8) | 7(4.0) |

| Housewife | 311(77.8) | 176(78.2) | 135(77.2) |

| Education level of father | |||

| Illiterate | 15(3.1) | 5(2.2) | 10(5.7) |

| Under high school | 109(27.3) | 69(30.6) | 40(22.8) |

| High school | 194(48.5) | 99(44.0) | 95(54.2) |

| College | 82(21.1) | 52(23.2) | 30(17.1) |

| Education level of mother | |||

| Illiterate | 13(3.2) | 4(1.8) | 9(5.1) |

| Under high school | 113(28.3) | 68(30.2) | 45(25.8) |

| High school | 211(52.8) | 110(48.9) | 101(57.8) |

| College | 63(15.7) | 43(19.1) | 20(11.5) |

Table 1: Sample characteristics for the total sample, and by help seeking behavior.

In this study, 82.9% of parents had a good attitude toward method of treatment, 83.4% toward causes, and 81.7% toward demonstrations of psychiatric disorders in children. In addition, 93.7% of parents had a good attitude toward mental illness in the three studied realms (Table 2). Of all, 56.25% of parents referred to official sources of help.

| Excellent | Good | Moderate | Attitude of parent toward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count(percent) | Count(percent) | Count(percent) | |

| 12(3.0) | 334(83.4) | 54(13.6) | Causes of children mental disorder |

| 17(4.3) | 332(82.9) | 51(12.8) | treatment methods of children mental disorders |

| 3(0.8) | 327(81.7) | 70(17.5) | behavioral demonstrations of children mental disorders |

| 0(0.0) | 370(92.5) | 30(7.5) | Mental disorder in children |

Table 2: Attitude of parents toward three domain of mental disorder of children.

The results revealed that there was a significant difference between mean scores of parents’ attitude towards the causes of psychiatric disorders in terms of child’s gender, number of children, marital status of parents, father’s job, and fathers’ and mothers’ education, so that, the parents of girls had a better attitude toward the causes of mental disorders in children (p<0.05). The attitude of parents who had three or less than three children were better than parents who had more than three children (p<0.05). Parents who were living together had a better attitude than parents who separated from each other (p<0.05). The parents of children whose fathers were government employee had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers were worker (p<0.01). In addition, parents of children whose fathers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers had high school diploma (p<0.001) or less than the diploma (p<0.001). The parents of children whose mothers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose mothers had high school diploma (p<0.001) or less than the diploma (p<0.001) There was no significant difference between the mean total scores of parents’ attitudes toward the causes of psychiatric disorders in terms of parent’s gender, mother’s job, and family income level (p>0.05). In addition, there was no significant correlation between parents’ attitude towards the causes of psychiatric disorders with child’s age and parents’ age (p>0.05).

There was no significant difference between mean scores of parents’ attitude towards demonstrations of mental disorders in children in terms of parent’s gender, parents’ age, child’s age, child’s gender, number of children, marital status, parent’s job and education level, and family income level (p>0.05).

The results showed that, based child’s gender, father’s job, father’s and mother’s education there were significant differences between parents’ attitude towards the method of treating psychiatric disorders, so that parents of girls had better attitude towards the treatment of mental disorders (p<0.01). In addition, parents of children whose fathers were government employee had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers were worker (p<0.01) and parents of children whose fathers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers had high school diploma or less than the diploma (p<0.001). The attitude of parents of children had a relationship with mother’s education level; parents of children whose mothers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose mothers had high school diploma or less than the diploma (p<0.001). The attitude of parents who had fewer than three children was significantly better than the parents who had more than three children (p<0.05). However, we did not find any significant difference between mean score of parents’ attitudes towards the treatment of psychiatric disorders in terms of parents’ gender, parents’ marital status, mothers’ job, and family level of income. In addition, there was no significant correlation between parents’ attitude towards the treatment of psychiatric disorders and children’s age and parents’ age (p>0.05).

The results of this research showed that there was a significant difference between the mean scores of parents’ attitude (sum of the three areas) in terms of child’s gender, parents’ marital status, father’s job, father’s education, and mother’s education. The parents of girls had a better attitude toward the causes of mental disorders (p<0.01). The parents of children whose fathers were government employee had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers were worker (p<0.01). In addition, parents of children whose fathers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose fathers had high school diploma (p<0.001) or less than the diploma (p<0.001). The parents of children whose mothers had academic education had better attitudes than parents of children whose mothers had high school diploma (p<0.001), less than the diploma (p<0.001), and illiterate mothers. There was no significant difference between the mean total scores of parents’ attitudes in terms of parent’s gender and age, age of child, number of children, marital status, mother’s job, and family income level (p>0.05). In addition, there was no significant correlation between parents’ attitude towards the causes of psychiatric disorders with child’s age and parents’ age (p>0.05).

Based on the results of our study, there was a significant relationship between help seeking behavior of parents and fathers’ education level, so that the official help seeking behavior were more prevalent among fathers with higher education levels (p<0.05). But there was no significant difference between help seeking behaviors of parents in terms of parents’ gender, age of children, number of children, marital status, mother’s job, and family income (p>0.05).

In addition, there was a significant difference between the mean scores of the parents’ attitudes toward the causes (p<0.001), behavioral demonstrations (p<0.001), and treatment methods (p<0.001) of mental disorders in children. Moreover, there was a significant difference between mean of scores of the three areas (p<0.001) in terms of parents’ help seeking behavior, so that parents with a better attitude referred more to formal sources of help.

Discussion

In this study it was found that 93.7% of parents had a good attitude toward mental illness of their children. In this study, there was no significant association between the genders of parents with the fields related to their attitudes toward mental illness. However, in some studies, women’s attitude toward mental disorders was found to be better than men’s attitude [32-34]. In this study, although there was no significant difference between the attitudes of parents, but help seeking behaviors of parents showed that mothers visited the medical centers more than fathers to get help for their children.

Based on the results of this study, there was no statistically significant correlation between parental attitudes and the mean age of parents. However, in a study by Ahn (2013) [35], the mean scores of individuals’ attitudes had an inverse relationship with their age. It is worth mentioning that Ahn’s study examined the attitudes of the general population and the mean age of the target group in that study was higher than that in our study. In addition, adoption is not common in Iran and consequently the average age of parents in this study was lower than that of Ahn’s study.

According to the results of this study, parents were mostly referred to mental health centers to treat the problem of their sons. Other studies have reported similar results [36-39].

No statistically significant correlation was observed between parents’ attitudes in three studied fields and the age of children. However, in a study by Pusstenin (2008) [40], parents of older children had a better attitude toward the psychiatric disorders of their children. This difference might be due to the higher age range of parents (37 to 39 years) and their children (8 to 12 years) which was higher than the age range of participants of our study. In this study, parents who were married and were living with their spouse had a better attitude than those who were widow, divorced, or married again. The results of other studies also showed that parents who were living in more intimate families had a better attitude towards mental illness of their children [41,42].

There was a significant statistical relationship between mean score of parental attitudes in all the three studied areas and the economic status of the household and it was found that parents living in families with higher economic level had a better attitude. Other studies, also reported similar results [43-45].

In this study a significant relationship was observed between the education level of fathers and parents’ attitudes toward method of treatment and the causes of mental disorders, so that 89% of fathers who had higher levels of education had better attitudes than the fathers who had lower levels of education. The results of this study are not consistent with the results of a similar study [46]. The major difference between our study and a study which was conducted in the USA was caused by studied population; that study was conducted on two major groups of Americans and African Americans populations and such obvious cultural differences affect attitude. However, some other studies reached the same conclusion [44,45,47].

This study examined the help seeking behaviors and at the end it was found that 65.25% of parents received help from official sources. Some studies obtained results which are consistent with the results of this study; according to their findings, more than half of the cases referred to the official sources of mental health services [48,49]. Some other studies showed that less than a third of adults referred to professional help services for treating their mental health problems [50-53]. The mentioned studies were conducted among students while the majority of participants in our study were parents with high school diploma or lower education levels.

In this study, mothers referred more for seeking help than fathers. Our results are in line with the results of many studies which reported that help seeking behavior was more common in women than men [54-58].

There was no significant difference between the mean ages of parents in terms of their help seeking behaviors. However, in some studies conducted on older people, the participants had a stigmatizing attitude and often referred to informal sources of help [36,37,59]. The difference between the results of these studies might be attributable to their study population. The previous studies examined the attitudes and behaviors of the public or patients; nonetheless, when a person becomes a parent, he or she undergoes a process that will change his or her behavior and attitudes. The study no significant difference was found between the first child and the other children of the family in terms of seeking help behaviors. The result of TEPFER’s study was consistent with our results [60].

In this study, there was no significant difference between the help seeking behaviors of parents in terms of child’s gender. These finding is not consistent with the results of some studies in which parents of boys tended to get assistance from official sources than parents of girls. This difference could be attributable to cultural and social differences of the studied populations [61,62]. In Iran, behavioral abnormalities in females is less acceptable for families, hence parents quickly refer to health care centers to solve such problems. On the other hand the number of male patients in this study was higher, and the two together led to a gender balance.

There was a significant relationship between help seeking behaviors of parents and education. As a result, 63.4% of the parents were referred to the official sources of help were fathers with higher education. The results of some studies suggest that people with higher education seek help from official sources more than others [35,63,64].

In this study, there was no significant relationship between the economic status of parents and their help seeking behaviors, but in some studies families with better economic status commonly used the official sources of help [35,36,65,66].

As one of the limitation of this study, we were unable to estimate the actual economic status of families because we used a qualitative and self-report tool to investigate family income. However, in most studies, this variable is measured quantitatively and is based on divisions made by reference economic institutions in the community.

Conclusion

Cultural and social growth and development of human resources depends on the health of society, and mental health is a key element of communities’ health. Since children are the future builders of every society, the health of human societies is dependent on children’s health. Mental disorders are among the most important risks threatening mental health of children; hence, on time recognition and appropriate actions by families to remedy the harmful effects of these disorders can decrease the harms. This study investigated the role of attitudes and demographic factors on help seeking behaviors and, overall, the results showed that parents had a good attitude toward their children’s mental disorders (93.75%). Moreover, more than half of parents were referring to formal sources of assistance to receive help for treating mental disorders of their children (56.25%). However, it should not be overlooked that nearly half of parents (43.75%) were still referring to unofficial sources of assistance. Therefore, it seems that there is a need to educate families and inform them more about the causes of mental disorders so that to generate a proper attitude in families toward children with mental disorder. In order to meet this goal, a variety of tools such as social mass media and publications be utilized at all levels of community including homes, schools, universities, offices, and organizations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the adolescents and families who participated in the research.

References

- Collins PY, Insel TR, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox YT (2013) Grand challenges in global mental health: Integration in research, policy, and practice. PLoS Medicine 10: e1001434.

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F (2005) Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe-a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 357-376.

- Rogers A, Pilgrim D (2014) A sociology of mental health and illness. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. (2008) Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world. Br J Psychiatry 192: 368-375.

- Nunnally J (1961) Popular conceptions of mental health, their development and change. New York: Holt Pp: 311.

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (1996) Relatives' beliefs about the causes of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93: 199-204.

- Whatley CD (1963) Status, role and vocational continuity of discharged mental patients. J Health Hum Behav 4: 105-111.

- Fung KM, Tsang HW, Corrigan PW, Lam CS, Cheung WM (2007) Measuring self-stigma of mental illness in China and its implications for recovery. Int J Soc Psychiatry 53: 408-418.

- Jorm AF (2000) Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 177: 396-401.

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H (2003) Public beliefs about schizophrenia and depression: Similarities and differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 38: 526-534.

- Magliano L, Fiorillo A, De Rosa C, Malangone C, Maj M (2004) Beliefs about schizophrenia in Italy: a comparative nationwide survey of the general public, mental health professionals, and patients' relatives. Can J Psychiatry 49: 322-330.

- Jorm AF, Mackinnon A, Christensen H, Griffiths KM (2005) Structure of beliefs about the helpfulness of interventions for depression and schizophrenia. Results from a national survey of the Australian public. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40: 877-883.

- Jackson HJ, MC Gorry PD (2009) The recognition and management of early psychosis: A preventive approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, McLeod JD, Jensen PS (2007) Comparison of public attributions, attitudes, and stigma in regard to depression among children and adults. Psychiatr Serv 58: 632-635.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ (1998) Early conduct problems and later life opportunities. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 39: 1097-1108.

- Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2002) Child and adolescent problems predict DSM-IV disorders in adulthood: A 14-year follow-up of a Dutch epidemiological sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41: 182-189.

- Stefl ME, Prosperi DC (1985) Barriers to mental health service utilization. Community Ment Health J 21: 167-178.

- Chadda RK, Agarwal V, Singh MC, Raheja D (2001) Help seeking behaviour of psychiatric patients before seeking care at a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry 47: 71-78.

- Starr S, Campbell LR, Herrick CA (2002) Factors affecting use of the mental health system by rural children. Issues Ment Health Nurs 23: 291-304.

- Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg ME, Gary F, Mason DM, Garvan CW (2005) Exploring help-seeking for ADHD symptoms: A mixed-methods approach. Harv Rev Psychiatry 13: 85-101.

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW (2003) Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res 30: 176-189.

- Garralda ME, Bailey D (1988) Child and family factors associated with referral to child psychiatrists. Br J Psychiatry 153: 81-99.

- Newman D, O'Reilly P, Lee SH, Kennedy C (2015) Mental health service users' experiences of mental health care: An integrative literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 22: 171-182.

- New M, Razzino B, Lewin A, Schlumpf K, Joseph J (2002) Mental health service use in a community head start population. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156: 721-727.

- Post RM, Leverich GS, Fergus E, Miller R, Luckenbaugh D (2002) Parental attitudes towards early intervention in children at high risk for affective disorders. J Affect Disord 70: 117-124.

- Reavley NJ, Cvetkovski S, Jorm AF (2011) Sources of information about mental health and links to help seeking: Findings from the 2007 Australian national survey of mental health and wellbeing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46: 1267-1274.

- Power AK (2005) Achieving the promise through workforce transformation: A view from the center for mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health 32: 489-495.

- Eiraldi RB, Mazzuca LB, Clarke AT, Power TJ (2006) Service utilization among ethnic minority children with ADHD: A model of help-seeking behavior. Adm Policy Ment Health 33: 607-622.

- ILNA. The prevalence of mental disorders in 6/23 percent tehran: ILNA; 2012 (cited 2012/10/14 2012/10/14 16:18:00).

- Leong FTL, Zachar P, Conant L, Tolliver D (2007) Career specialty preferences among psychology majors: Cognitive processing styles associated with scientist and practitioner interests. The Career Development Quarterly 55: 328-338.

- Mackenzie CS, Erickson J, Deane FP, Wright M (2014) Changes in attitudes toward seeking mental health services: A 40-year cross-temporal meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 34: 99-106.

- Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ (2006) Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Ment Health 10: 574-582.

- Ahn D (2013) Perceptions of mental illness and attitude toward seeking professional psychological help among Korean clergymen in America. Alliant International University.

- Koydemir-Ozden S, Erel O (2010) Psychological help-seeking: Role of socio-demographic variables, previous help-seeking experience and presence of a problem. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 5: 688-693.

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hwang WC (2002) Predictors of help seeking for emotional distress among Chinese Americans: Family matters. J Consult Clin Psychol 70: 1186-1190.

- Bebbington PE, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Farrell M, Jenkins R, et al. (2003) Unequal access and unmet need: Neurotic disorders and the use of primary care services. Psychol Med 30: 1359-1367.

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, et al. (2007) Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the national Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health 97: 91-98.

- Puustinen M, Lyyra A-L, Metsapelto RL, Pulkkinen L (2008) Children's help seeking: The role of parenting. Learning and Instruction 18: 160-171.

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Mason DM, Meyer JM, White K, et al. (2012) ADHD knowledge, perceptions, and information sources: Perspectives from a community sample of adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health 51: 593-600.

- DosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, Beltran A, Riley AW, et al. (2009) The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents' initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19: 377-383.

- Chou KL, Mak KY (1998) Attitudes to mental patients among Hong Kong Chinese: A trend study over two years. Intr J Soc Psychiatry 44: 215-224.

- Pereira FM, Pereira NA (2003) Psychologists in Brazil: Notes about their professionalization process. Psicologia em estudo 8: 19-27.

- Andersson HW, Bjorngaard JH, Kaspersen SL, Wang CE, Skre I, et al. (2010) The effects of individual factors and school environment on mental health and prejudiced attitudes among Norwegian adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45: 569-577.

- Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW (2003) Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res 30: 176-89.

- Jorm AF, Wright A (2007) Beliefs of young people and their parents about the effectiveness of interventions for mental disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 41: 656-666.

- Jorm AF, Wright A (2008) Influences on young people's stigmatising attitudes towards peers with mental disorders: National survey of young Australians and their parents. Br J Psychiatry 192: 144-149.

- Corrigan PW (2011) Best practices: Strategic stigma change (SSC): Five principles for social marketing campaigns to reduce stigma. Psychiatric Services 62: 824-826.

- Woodward AT, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS (2010) Differences in professional and informal help seeking among older African Americans, Black Caribbeans and non-Hispanic Whites. J Soc Social Work Res 1: 124.

- Kabir M, Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Aliyu MH (2004) Perception and beliefs about mental illness among adults in Karfi village, northern Nigeria. BMC International Health and Human Rights 4: 3.

- Yi SH, Tidwell R (2005) Adult Korean Americans: Their attitudes toward seeking professional counseling services. Community Ment Health J 41: 571-580.

- So DW, Gilbert S, Romero S (2005) Help-seeking attitudes among African American college students. College Student J 39: 806.

- Aalto-Setälä T, Marttunen M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Poikolainen K, Lönnqvist J (2002) Psychiatric treatment seeking and psychosocial impairment among young adults with depression. J Affect Disord 70: 35-47.

- Fortune S, Sinclair J, Hawton K (2008) Help-seeking before and after episodes of self-harm: A descriptive study in school pupils in England. BMC Public Health 8: 369.

- Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P (2005) Men and health helpâ€seeking behaviour: Literature review. J Adv Nurs 49: 616-623.

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR (2003) Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American psychologist. Am Psychol 58: 5.

- Masuda A, Anderson PL, Edmonds J (2012) Help-seeking attitudes, mental health stigma, and self-concealment among African American college students. J Black Studies 43: 773-786.

- Bebbington P, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Farrell M, Jenkins R, et al. (2003) Unequal access and unmet need: Neurotic disorders and the use of primary care services. Psychol Med 15: 115-122.

- Tepfer B (2009) Predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes, willingness toward psychological service utilization, and levels of previous psychological service utilization among orthodox Jewish parents. City University of New York.

- Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, et al. (2004) Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43: 960-970.

- Bathje GJ, Pryor JB (2011) The relationships of public and self-stigma to seeking mental health services. J Mental Health Counseling 33: 161-176

- Vogel DL, Wester SR, Wei M, Boysen GA (2005) The role of outcome expectations and attitudes on decisions to seek professional help. J Counseling Psychology 52: 459.

- Shechtman Z, Vogel D, Maman N (2010) Seeking psychological help: A comparison of individual and group treatment. Psychotherapy Research 20: 30-36.

- Riedel-Heller SG, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2005) Mental disorders-who and what might help? Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40: 167-174.

- Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC (2008) Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: What do we know? Epidemiologia e psichiatria sociale. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 17: 31-7.

Citation: Ebrahimi H, Movaghari RM, Bazghaleh M, Abbasi A, Ohammadpourhodki RM (2019) Assessment of Attitude of Parents toward Children’s Mental Disorder and its Relation with Parents Helps Seeking Behaviors. J Comm Pub Health Nursing 5:225.

Copyright: © 2019 Ebrahimi H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 3258

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 19, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2544

- PDF downloads: 714