Research Article Open Access

Assessing Technical and Economic Feasibility of Complete Bioremediation for Soils Chronically Polluted with Petroleum Hydrocarbons

Roberto Orellana#, Andres Cumsille#, Claudia Rojas, Patricio Cabrera, Michael Seeger*, Franco Cárdenas, Cristian Stuardo and Myriam González

Molecular Microbiology and Environmental Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Chemistry and Center of Biotechnology, Universidad Técnica Federico Santa Maria, Valparaiso, Chile

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michael Seeger

Molecular Microbiology and Environmental Biotechnology Laboratory

Department of Chemistry and Center of Biotechnology

Universidad Técnica Federico Santa Maria, Valparaiso, Chile

Tel: 56322654236

Fax: 56322654782

E-mail: michael.seeger@usm.cl

Received Date: May 07, 2017; Accepted Date: May 17, 2017; Published Date: May 19, 2017

Citation: Orellana R, Cumsille A, Rojas C, Cabrera P, Seeger M, et al. (2017) Assessing Technical and Economic Feasibility of Complete Bioremediation for Soils Chronically Polluted with Petroleum Hydrocarbons. J Bioremediat Biodegrad 8:396. doi: 10.4172/2155-6199.1000396

Copyright: © 2017 Orellana R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Bioremediation & Biodegradation

Abstract

Petroleum hydrocarbons are highly persistent in the environment and represent a significant risk for humans, biodiversity, and the ecosystems. Frequently, hydrocarbon-contaminated sites remain polluted for decades due to a lack of proper decontamination treatments. Although bioremediation techniques have gained attention for being environmentally friendly, cost-effective and applicable in situ, their application is still limited. Each polluted soil has particularities, therefore, the bioremediation approach for a contaminated site is unique. Bioremediation cost studies are usually based on hypothetical assumptions rather than technical or experimental data. The research aims of this study were to clean-up chronically hydrocarbon-polluted soils using aerobic and anaerobic bioremediation techniques and to carry out an economic evaluation of the most promising bioremediation treatments. The results showed that aerobic biostimulation with vermicompost and aerobic bioaugmentation plus air venting were the most effective treatments, degrading 78% and 73% of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in chronically hydrocarbonpolluted soils after six weeks, respectively. In contrast, no significant degradation of hydrocarbon was observed by anaerobic biostimulation treatments with lactate and acetate. An economic evaluation of the aerobic treatments were carried out. This analysis revealed that the cost of treating one cubic meter of soil by biostimulation is US$ 59, while bioaugmentation costs US$77. This study provides a clear structure of costs for both aerobic bioremediation approaches based on projections made from these lab-scale incubations. These values represent the first step towards a better understanding of the feasibility of such treatments at larger scales, which is crucial to move on industrial bioremediation of soils chronically polluted with petroleum hydrocarbons.

Keywords

Bioaugmentation; Bioremediation; Biostimulation; Petroleum hydrocarbon; Hydrocarbon-degrading strain; Acinetobacter; Pseudomonas

Introduction

Petroleum based products are the major source of energy in industry and daily life [1]. Leaks and accidental spills during the manipulation, transportation, and storage of petroleum products are frequent, therefore, petroleum hydrocarbon contamination is a global concern [2,3]. Petroleum hydrocarbons are highly persistent in the environment and represent a significant risk for human health, impacting the biodiversity and the ecosystems around the world [4,5]. In 2002, the European Union estimated 18,142 contaminated sites, where 53% of them were affected with mineral oil and common petroleum substances [6,7]. In Australia, from 160,000 contaminated locations, 60% comprised hydrocarbon-contaminated sites [8]. Frequently, a large fraction of those sites remains polluted for decades, mainly due to the lack of appropriate decontamination treatments [9].

Bioremediation is the process that applies living organisms to degrade, reduce or detoxify pollutants [10,11]. Bioremediation techniques are often based on (i) natural bioattenuation, using indigenous microorganisms to degrade a pollutant; (ii) biostimulation, changing variables to enhance pollutant degradation by native communities; or (iii) bioaugmentation, using exogenous hydrocarbon clastic microorganisms [12]. Although bioremediation has gained increasing attention for being an environmentally sustainable, costeffective and a permanent alternative for treatment of contaminated soils with a wide range of pollutants, its contribution for the clean-up is still limited [13,14]. Nutrient limitations, insufficient availability of electron acceptors, and the lack of an efficient catabolic machinery from native microbial communities are among the main factors preventing bioremediation for massive application [4,11,15]. Other remediation techniques, such as physical separation, in-situ chemical injection, application of ozone or electrochemical degradation have been seldomly applied due to their high costs and energy consumption, along with physicochemical alterations of the remediated soils [16].

The ultimate goal of bioremediation of petroleum-contaminated sites is to degrade hydrocarbons into carbon dioxide and water [17]. However, the assessment of efficacy and efficiency of bioremediation of a wide range of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils has become rather challenging. Indeed, the available regulations to assess when a site should be classified as cleaned are variable. For instance, the maximum concentration limit of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) allowed in Spain is 50 ppm for soils, while in the United States the action levels range from 10,000 to 100 ppm [18,19]. However, 100 ppm was the most commonly applied clean-up level [18,19]. Thereafter, the policies for management of contaminated sites have evolved from a total concentration to a risk-assessment standpoint. This perspective is based on the potential risks to humans and ecosystems that would occur under “standardized” condition [7,20]. This complexity makes every bioremediation approach unique for a particular region and condition, and it is difficult to compare each impacted soil taking into account their different particularities, treatments, and extraction procedures [21].

Despite that bioremediation is recognized to be a suitable approach to deal with hydrocarbon polluted sites, dig and dump techniques are still widely preferred [4,6]. Mainly, this is due to the time and cost of the bioremediation process that limits its higher contribution as a treatment for contaminated soil [22-24]. This claim is still subject of debate since these observations are based on hypothetical assumptions that are difficult to verify, rather than on technical or experimental data [25,26]. Furthermore, bioremediation studies have been regularly oriented towards environments that have been abruptly impacted with high concentrations of hydrocarbons (e.g., after spills), showing a tendency to present higher rates of degradation of contaminants (i.e., TPH) starting from a high concentration, but leaving still high concentration after biodegradation rates slow do [17,25,27]. The conclusions of such studies raise the question whether bioremediation has to be complemented with additional physicochemical treatments before its restoration into industrial, agricultural, or domestic areas. More importantly, they leave aside those soils that are chronically contaminated with lower, but more recalcitrant contaminants, which have been scarcely reported.

In this study, a set of aerobic and anaerobic lab-scale microbial incubations to assess bioremediation approaches of soils chronically contaminated with hydrocarbons were employed. The treatments were applied to soils that contain an initially low concentration of hydrocarbons (500-800 ppm), which constrain the degradation rates along the experiment. The goal was that soils after bioremediation achieve a TPH concentration of 100 ppm. Two aerobic treatments were used: i) biostimulation by the addition of compost, and ii) bioaugmentation plus air venting. In addition, two anaerobic treatments based on biostimulation by the addition of two different organic acids were studied. Both aerobic treatments effectively degraded more than 70% of the initial TPH concentration, while anaerobic treatments did not present significant degradation rates. Furthermore, these results we projected to an industrial-scale bioremediation effort and the composition and structure of the costs for both aerobic treatments were evaluated. The results suggest that aerobic biostimulation with compost (40% v/v) is the most costeffective treatment to deal with the chronically petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soils.

Materials and Methods

Site description and sampling

Samples were collected from a hydrocarbon-polluted soil (Chile), which was used for over 80 years as a fuel storage pond, as well as to produce oil lubricants, agrochemicals, and household cleaning products. Approximately 30 kg of polluted soils were collected in the saturated zone, at the water column, and another 30 kg were collected in the unsaturated zone of the site. Soil samples were collected and transported immediately to a refrigerated chamber (4°C).

Aerobic microcosms

The aerobic microcosms comprised three experimental sets in triplicate: a non-treated control soil (AC), a soil subjected to biostimulation (ABE) and a soil subjected to bioaugmentation and air venting (AV). The AC microcosms consisted of flasks containing 1 L of polluted soil from the contaminated site. The ABE microcosm is a mixture of polluted soil from the site and vermicompost (40% v/v). The AV treatment consisted of the same polluted soil mentioned above, but bioaugmented weekly with five hydrocarbonoclastic strains: three belonging to Acinetobacter genus (Acinetobacter sp. 78, Acinetobacter sp . AA64 and Acinetobacter sp. AF53) and two Pseudomonas strains (Pseudomonas sp . DN36, and Pseudomonas sp . DN34). These strains were isolated from chronically hydrocarbon-contaminated soil located in the Aconcagua River (Valparaíso Region, Chile) and possess the ability to utilize a wide range of hydrocarbons as sole carbon sources [12]. In addition to their degrading potential, Acinetobacter sp . 78 was added to the consortium due to its remarkable capability to produce biosurfactants, allowing hydrocarbon emulsification and enhancing its bioavailability [28]. Additionally, the AV microcosms were provided with an air flux through the 1 L flask. Cells were grown in Bushnell- Haas (BH) broth containing (in grams per liter of Milli-Q water): KH2PO4, 1; K2HPO4, 1; NH4NO3, 1; MgSO4, 0.2; CaCl2, 0.020; FeCl3, 0.050; pH=7.0) at 30°C until late exponential phase (turbidity 600 nm∼1.0).

Anaerobic microcosms

In a first step, the Terminal Electron Accepting Process (TEAP) was identified. Fe(II)/Fetotal ratio, nitrate, and sulfate concentration were monitored for one month in 500 mL flasks with 150 mL of polluted soil saturated with a 2 cm water column inside an anaerobic chamber. Three treatments in triplicate were carried out to assess the TEAP: a treatment with lactate stimulation (10 mM), a treatment with acetate stimulation (10 mM), and a control without stimulation.

Subsequently, three different anaerobic microcosms were performed in triplicate: a non-treated control (NOC) soil, a soil subjected to lactate (10mM) biostimulation (NOBEL) and a soil subjected to acetate (10mM) biostimulation (NOBEA). The anaerobic microcosms consisted of 1 L of soil samples from the polluted site, with a water column of approximately 10 cm. Standard anaerobic techniques were used throughout the study. Anaerobic lactate and acetate were boiled and cooled under a constant stream of 80% N2 and 20% CO2, dispensed into aluminum-sealed culture tubes under the same gas phase, capped with butyl rubber stoppers, and sterilized by autoclaving (121°C, 20 min). Additions to sterile medium, inoculation, and sampling were done by using syringes and needles. All incubations were placed in an anaerobic chamber under darkness at 30°C.

Heterotrophic bacteria plate counting

Bacterial plate count experiments were performed for every aerobic treatment microcosm with the drop plate technique [29]. Briefly, 1 g of sample, with a known humidity was diluted in 9 mL saline solution (NaCl 0.85% w/v) and mechanically disrupted with a FastPrep-24 bead beater (MP, Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) for 1 h. The sample was then serially diluted and from every dilution, a 10 μL drop was placed in triplicate in TSA medium. The plates were sealed and incubated for 24 hours at 30°C. All visible colonies were counted. The results were normalized to UFC g-1 of dry weight soil.

Soil characterization

Soil pH was determined in an aqueous soil suspension with a pH meter. The humidity was determined by thermogravimetric methods using an electronic analyzer (Sartorius MA35). Sulfate quantification was performed according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) method 375.4 [30]. The method consists in the precipitation of the sulfate ion with barium chloride in acid media and the measurement of absorbance. Nitrate quantification was performed spectrophotometrically as previously described [31]. Iron quantification was measured with the method of reduction of crystalline ferric iron by hydroxylamine under acidic conditions, and the subsequent accumulation of ferrous iron [32].

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) quantification

The total petroleum hydrocarbon quantification method is based on the EPA method 8015B [33]. In this method, 5 g of soil sample was mixed with 100 μL of a standard solution (1-chlorooctadecane 250 ppm) in a 100-mL glass bottle. Then, 25 mL of a NaCl-saturated solution and 5 mL of hexane was added. The samples were then sonicated (Cientec Ultrasonik 300) at 60°C for 40 min and vigorously shaken every 5 min. After two hours, samples were transferred to a 50- mL polypropylene tube and centrifuged at 4,000 ×g 10 min. The organic fraction was transferred to a sealed vial and stored at -20°C until analysis. To estimate the degradation of compounds belonging to the diesel range organics (DRO), including from C12 to C28 hydrocarbons (here after called TPH), quantification of hydrocarbons was performed every week, with exception of week number five after the beginning of the experiment. The procedure was accomplished as previously described [12], with minor modifications, injecting 2 μL of the sample in a gas chromatograph coupled with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) (Clarus 680, PerkinElmer). Briefly, the injector temperature was 320°C, the detector temperature was 295°C, the flow was split less during injection at 10 ml min-1. After 0.5 mins, 1:30 split was opened and the flow decreased to 1 ml min-1 and was held constant. The thermal profile was 3 min at 45°C, the first ramp of 12°C min-1 until 275°C, the second ramp raised 50°C min-1 until 310°C, and was kept at 310°C for 11 min. Standard curves were constructed with the DRO-1 standard (Dr. Ehrensdorfer GmbH, Augsburg, Germany).

Costs analyses

The economic evaluation of the two most effective bioremediation treatments was projected in a horizon of a ten-year scenario. The data used in this evaluation was obtained from the lab-scale aerobic treatments of this study.

For both cases, a period of six weeks and the use of an area of one hectare for the plant treatment was considered. In this area, the contaminated soil is predicted to be treated in biopiles of 3 m height, 5 m base, and 100 m length, leaving 5 m space between the biopiles. Therefore, one hectare can hold 10 biopiles, resulting in a total of 7,500 cubic meters of contaminated soil for the AV plant and 4,500 cubic meters for the ABE plant, which considers a 40% (v/v) of compost for the bioremediation.

Proposed amounts are the result of this study and an estimation of different costs considered in the implementation and operation of a bioremediation process, which are: (i) initial investment, (ii) operational costs (maintenance, personnel, supplies, and services), and (iii) marketing and administration. The costs of the equipment, personnel, supplies and services were estimated considering the current market availability. In general, ABE treatment plant considered two front shovel loaders for landfarming and a spray truck to maintain humidity of the biopiles. The AV treatment included one front shovel loader and a spray truck, for spreading the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria into the biopiles. The plants are planned to operate in a continuous turnover.

Results and Discussion

Removal of TPH during bioremediation

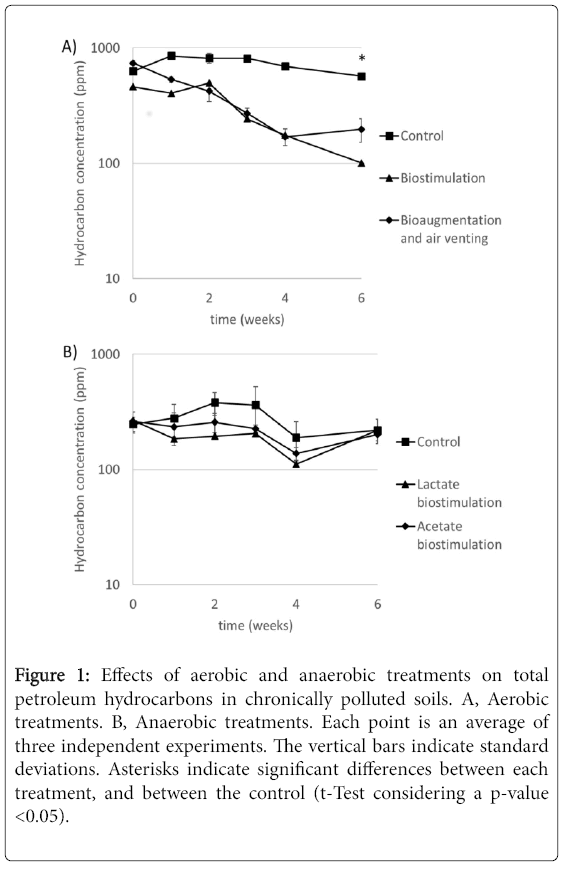

In order to clean-up chronically petroleum hydrocarboncontaminated soils, aerobic incubations of 1 L under two types of bioremediation treatments were carried out for six weeks. The treatments were based on a single addition of vermicompost 40% v/v (biostimulation) and the periodic inoculation of five HC-degrading strains plus air venting (bioaugmentation). Gas chromatographic analysis was performed to estimate the degradation of compounds belonging to the diesel range organics (DRO), including from C12 to C28 hydrocarbons. The effect of the aerobic bioremediation treatments on the concentrations of TPH is shown in Figure 1A. A high decrease in the hydrocarbon concentration by both aerobic treatments was observed. After six weeks, the hydrocarbon fraction decreased in 78% and 73% by ABE and AV treatments, respectively. In contrast, the TPH in the abiotic control decreased only 9%. In both ABE and AV treatments, no significant changes in humidity and pH along the experiment were observed (Figures S2 and S3).

Figure 1: Effects of aerobic and anaerobic treatments on total petroleum hydrocarbons in chronically polluted soils. A, Aerobic treatments. B, Anaerobic treatments. Each point is an average of three independent experiments. The vertical bars indicate standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between each treatment, and between the control (t-Test considering a p-value <0.05).

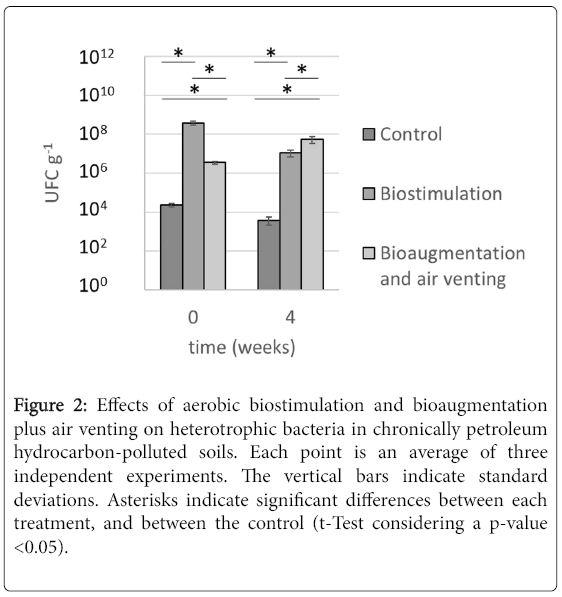

Although the overall rates of degradation of both treatments were similar (~22% during the whole experiment), the kinetic of degradation of the bioremediation process revealed significant differences. The rate of degradation of hydrocarbons in the AV treatment until the fourth week followed a first order kinetic; thereafter, no further degradation was registered (Table S1). Similar degradation pattern was reported in previous studies carried out with other chronically contaminated soils. For example, a report [9] showed that although using soils contaminated with a 10-fold higher concentration of hydrocarbons compared to this study, the augmentation treatments degraded TPH at the highest rate during the first two weeks, slowing down its effects afterwards. In those incubations, the soils remained with 2,924 ppm of TPH after bioaugmentation during 45 days [9]. The degradation kinetic of the AV treatment correlates with the data obtained with heterotrophic bacterial plate counts (Figure 2). After four bacterial additions, there was a 10-fold increase in heterotrophic bacteria. Therefore, despite the fact that half of the bacterial biomass was added during weeks five and six, there was not further hydrocarbon degradation observed during that period, suggesting that the microbial consortia added were not capable of scavenging hydrocarbons below such low concentration (170 ppm).

Figure 2: Effects of aerobic biostimulation and bioaugmentation plus air venting on heterotrophic bacteria in chronically petroleum hydrocarbon-polluted soils. Each point is an average of three independent experiments. The vertical bars indicate standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences between each treatment, and between the control (t-Test considering a p-value <0.05).

After two weeks of the ABE treatment, the rate of hydrocarbon degradation started following a first order kinetic. However, in this case, the degradation continued until a hydrocarbon concentration in the soil. In this study, 100 ppm hydrocarbon concentration in soil was used towards classifying the soil as cleaned-up (bioremediated). Since the treatment was amended with humus, ABE had 40% lower hydrocarbon concentration at the start of the experiment than the AV treatment. At lower concentration, hydrocarbons are less bioavailable for the microbiota. However, the results suggest that bioavailability was not a problem for the ABE treatment since the microbial community was able to degrade hydrocarbons until a lower final concentration than in the AV treatment. These results suggest that degrading microorganisms of the compost, which is a substrate that is rich in organic matter and contains a substantial number of microorganisms, (Figure 2), t degrade hydrocarbons at low concentrations. In addition, compost is a rich source of nutrients that could support the growth of native microbial hydrocarbon clastic communities responsible for the sustained degradation of hydrocarbons.

AV treatment was carried out with the addition of a consortium of five bacterial strains that were previously isolated and characterized by our group [12,28]. The consortium was composed of two strains belonging to Pseudomonas and three strains from Acinetobacter genus. Acinetobacter strains are among the most abundant and ubiquitous microorganisms in soils and wastewater [34-39]. Notably, Acinetobacter strains are ubiquitous in oil-contaminated environments [40-42]. Acinetobacter isolates are generally equipped with an array of enzymes and degrading capabilities towards metabolizing alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons [43-45]. These enzymes include several dioxygenases, 1-acenaphthenol dehydrogenases, and salicylaldehyde dehydrogenases [46]. On the other hand, the genus Pseudomonas are also commonly present in hydrocarbon-contaminated environments [47-49] and their metabolism includes the degradation of various aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons [9,12,50-52]. Both Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter strains are also well known to produce a wide variety of extracellular emulsifiers towards improving the bioavailability of hydrocarbons [53-57]. These emulsifiers may increase the aqueous solubility of hydrocarbons up to 20-fold [58]. In general, bioaugmentation approaches favor the addition of bacteria capable of simultaneously metabolize hydrocarbons at fast rates and produce biosurfactants [59,60].

In a second approach, bioremediation of chronically petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated soil was carried out under anaerobic conditions. This approach includes the preparation of 1 L microcosms incubated in an anaerobic chamber at 30°C. The first step was the determination of sulfate reduction as the predominant TEAP in the sediments (Figures S1). Therefore, acetate and lactate were added as electron donors to stimulate native microbial communities. The results of acetate and lactate additions showed a significant reduction of the concentration of sulfate in the two biostimulation treatments (Figure S4). Unfortunately, the stimulation of sulfate-reducing community did not encompass a TPH reduction during the 6 weeks of the experiment (Figure 1B). These results suggest that adding other electron donors, as acetate and lactate, produce a direct competition for the hydrocarbons, rather than a higher consumption of TPH as a result of the microbial bloom induced by the higher availability of electron donors.

In conclusion, these results indicate that both aerobic bioremediation treatments (ABE and AV) were capable of degrade the petroleum hydrocarbons during the 6 weeks incubations. The results suggest that ABE treatment may be the most promising strategy for bioremediation of low level chronically contaminated soils. Probably vermicompost is a good source of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria that were capable of degrading TPH until a lower concentration than the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria used in the AV treatment. Moreover, vermicompost provides nutrients that may stimulate the activity of native hydrocarbonoclastic communities [61,62]. Notably, treating contaminated soils with vermicompost provides additional advantages: easy application (only at the beginning of the experiment), provides long term nutrient sources and no requires additional expenses (e.g., air venting). The results of this study contrasted with a previous report, where bioaugmentation showed higher TPH degradation rates than biostimulation [13]. These differences highlighted the need to study the effects of the incorporation of lower concentration of organic materials. As part of this endeavor, we are currently running an outdoor experiment using bioremediation of hydrocarbon contaminated soils by the addition of 10% compost, instead of vermicompost, which is a cheaper source of nutrients and microorganisms.

Costs evaluation of the scale-up of aerobic treatments

A costs evaluation of the two more effective bioremediation treatments, AV and ABE, at an industrial-scale in a scenario of ten years were carried out. The results indicate that the costs varied from US$77-112 and US$59-86 per cubic meter of treated soil for bioaugmentation and biostimulation, respectively (Tables S2-S19). These amounts include the following items: (i) initial investment, (ii) operational costs (maintenance, personnel, supplies and services), and (iii) marketing and administration The costs considered a plant treatment capacity for the contaminated soil of 65,000 cubic meters per year, in the case of AV, and 39,000 cubic meters per year for ABE treatment (Table S1).

The polluted soil has to be amended with 40% w/w of vermicompost, whose value corresponds to the most important item in the ABE treatment, covering a 90% (US$ 53 per cubic meter) of the total cost of the treated soil (Table S16). A cost of US $30 per ton of vermicompost was assumed. Therefore, lower-cost alternative substrates could be attempted towards a reduction of the overall cost of the treatment. On the other hand, the most important item in the AV treatment corresponds to BHB medium that is used for growth of the hydrocarbon-degrading strains applied during augmentation. For each cycle of treatment of 7,500 cubic meters of contaminated soils, a consumption of 487 cubic meters of BHB medium was calculated (Table S16). Such utilization of high-quality reagents makes its value rise to US$ 69.7 per cubic meter of treated soil, covering also a 90% of the total cost of the AV treatment.

The costs of biostimulation and bioaugmentation calculated by our study are in the range reported previously [4]. However, other studies indicate that the cost of similar treatments was more than 50% lower [25,26] suggesting the high sensibility of those calculations demand to be extremely careful in the extrapolation to industrial scale application. Other alternatives for the treatment of contaminated soils have also been evaluated economically based on 169 pollution remediation actions [63], established that the cost of a dig and dump treatment is in the range US$140-380 per cubic meter of treated soil. These treatments are more expensive that the ABE and AV treatments of this study, and do not remove the contamination in soils.

The results of this study provide a clear structure of costs for two aerobic bioremediation approaches based on projections made from 1 L microcosms. The extrapolating the results obtained from such labscale incubations to industrial-scale treatments shows risks. However, it is the first step towards a better understanding of the feasibility of those treatments. These current limitations emphasize the need for more detailed analysis in field or semi-industrial scale studies, which are crucial to further explore industrial bioremediation of soils polluted with petroleum hydrocarbons.

Conclusions

In this study, both aerobic treatments were more effective in degrading TPH from a chronically petroleum hydrocarbon-polluted soil than the anaerobic approaches. The results suggest that biostimulation with vermicompost (40% v/v) is the most promising strategy for bioremediation of low-level chronically hydrocarboncontaminated soils. The concentration of TPH after six weeks were lower by biostimulation than by bioaugmentation. An economic evaluation of the aerobic treatments revealed that the cost of treating one cubic meter of soil by biostimulation was also lower. This study provides a clear structure of costs for these two types of bioremediation approaches and gives insights towards a better understanding of the feasibility of such treatments at larger scales.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONDECYT 1151174 to MS) with additional funding from the Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María (USM 131562 and CBDAL to MS). FC acknowledges Conicyt PhD fellowship.

References

- Joshi MN, Dhebar SV, Dhebar SV, Bhargava P, Pandit AS, et al. (2014) Metagenomic approach for understanding microbial population from petroleum muck. Genome Announc 2: e00533-14.

- Kvenvolden KA, Cooper CK (2003) Natural seepage of crude oil into the marine environment. Geo-Mar Lett 23: 140-146.

- Nikolopoulou M, Pasadakis N, Kalogerakis N (2013) Evaluation of autochthonous bioaugmentation and biostimulation during microcosm-simulated oil spills. Marine Pollution Bulletin 72: 165-173.

- Fuentes S, Méndez V, Aguila P, Seeger M (2014) Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons: catabolic genes, microbial communities, and applications. ApplMicrobiolBiotechnol 98: 4781-4794.

- Jung J, Philippot L, Park W (2016) Metagenomic and functional analyses of the consequences of reduction of bacterial diversity on soil functions and bioremediation in diesel-contaminated microcosms. Sci Rep 6: 23012.

- Majone M, Verdini R, Aulenta F, Rossetti S, Tandoi V, et al. (2015) In situ groundwater and sediment bioremediation: barriers and perspectives at European contaminated sites. New Biotechnology 32: 133-146.

- Pinedo J, Ibanez R, Lijzen JPA, Irabien A (2013) Assessment of soil pollution based on total petroleum hydrocarbons and individual oil substances. Journal of Environmental Management 130: 72-79.

- Thavamani P, Smith E, Kavitha R, Mathieson G, Megharaj M, et al. (2015) Risk based land management requires focus beyond the target contaminants - a case study involving weathered hydrocarbon contaminated soils. Environmental Technology & Innovation 4: 98-109.

- Ruberto L, Dias R, Lo Balbo A, Vazquez SC, Hernandez EA, et al. (2009) Influence of nutrients addition and bioaugmentation on the hydrocarbon biodegradation of a chronically contaminated Antarctic soil. Journal of Applied Microbiology 106: 1101-1110.

- Boopathy R (2000) Factors limiting bioremediation technologies. Bioresource Technology 74: 63-67.

- Perelo LW (2010) Review: In situ and bioremediation of organic pollutants in aquatic sediments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 177: 81-89.

- Fuentes S, Barra B, Caporaso JG, Seeger M (2016) From rare to dominant: a fine-tuned soil bacterial bloom during petroleum hydrocarbon bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol 82: 888-896.

- Bento FM, Camargo FAO, Okeke BC, Frankenberger WT (2005) Comparative bioremediation of soils contaminated with diesel oil by natural attenuation, biostimulation and bioaugmentation. Bioresource Technology 96: 1049-1055.

- Sanscartier D, Reimer K, Koch I, Laing T, Zeeb B (2009) An investigation of the ability of a 14C-labeled hydrocarbon mineralization test to predict bioremediation of soils contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons. Bioremediation Journal 13: 92-101.

- Li WW, Yu HQ (2015) Stimulating sediment bioremediation with benthic microbial fuel cells. Biotechnology Advances 33: 1-12.

- Hashim MA, Mukhopadhyay S, Sahu JN, Sengupta B (2011) Remediation technologies for heavy metal contaminated groundwater. Journal of Environmental Management 92: 2355-2388.

- Sarkar D, Ferguson M, Datta R, Birnbaum S (2005) Bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons in contaminated soils: comparison of biosolids addition, carbon supplementation, and monitored natural attenuation. Environmental Pollution 136: 187-195.

- Bradley LJN, Magee BH, Allen SL (1994) Background levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and selected metals in New England urban soils. Journal of Soil Contamination 3: 349-361.

- Kostecki PT, Calabrese EJ (1993) Hydrocarbon Contaminated Soils. CRC Press, Florida, USA.

- Karlen DL, Ditzler CA, Andrews SS (2003) Soil quality: Why and how? Geoderma 114: 145-156.

- MaletiĬ? SP, Dalmacija BD, RonĬćeviĬ? SD, Agbaba JR, PeroviĬ? SDU (2011) Impact of hydrocarbon type, concentration and weathering on its biodegradability in soil. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part A 46: 1042-1049.

- Agamuthu P, Tan YS, Fauziah SH (2013) Bioremediation of hydrocarbon contaminated soil using selected organic wastes. Procedia Environmental Sciences 18: 694-702.

- Azubuike CC, Chikere CB, Okpokwasili GC (2016) Bioremediation techniques–classification based on site of application: principles, advantages, limitations and prospects. World J MicrobiolBiotechnol 32: 180.

- Yergeau E, Sanschagrin S, Beaumier D, Greer CW (2012) Metagenomic analysis of the bioremediation of diesel-contaminated canadian high arctic soils. PLoS ONE 7: e30058.

- Adams RH, Guzmán-Osorio FJ (2008) Evaluation of land farming and chemico-biological stabilization for treatment of heavily contaminated sediments in a tropical environment. Int J Environ Sci Technol 5: 169-178.

- Agunwamba JME (2013) Cost comparison of different methods of bioremediation. Int J Curr Sci 7: 9-15.

- Margesin R, Hämmerle M, Tscherko D (2007) Microbial activity and community composition during bioremediation of diesel-oil-contaminated soil: effects of hydrocarbon concentration, fertilizers, and incubation time. MicrobEcol 53: 259-269.

- Aguila P (2014) Bioaugmentation effect of a native bacterial consortium and the biostimulation with a biosurfactant on hydrocarbon polluted soils. PhD thesis in Biotechnology UTFSM-PUCV. Valparaiso, Chile.

- Herigstad B, Hamilton M, Heersink J (2001) How to optimize the drop plate method for enumerating bacteria. Journal of Microbiological Methods 44: 121-129.

- USEPA (1971) Methods for the chemical analysis of water and wastes.

- Cataldo DA, Maroon M, Schrader LE, Youngs VL (1975) Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 6: 71-80.

- Lovley DR, Phillips EJP (1987) Rapid Assay for microbially reducible ferric iron in aquatic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 53: 1536-1540.

- USEPA (1996) Total Petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) as Gasoline and Diesel: SW-846 Method 8015B.

- Bashir M, Ahmed M, Weinmaier T, Ciobanu D, Ivanova N, et al. (2016) Functional metagenomics of spacecraft assembly cleanrooms: presence of virulence factors associated with human pathogens. Frontiers in Microbiology 7: 1321.

- Broszat M, Nacke H, Blasi R, Siebe C, Huebner J, et al. (2014) Wastewater irrigation increases the abundance of potentially harmful Gammaproteobacteria in soils in Mezquital valley, Mexico. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 80: 5282–5291.

- Connon SA, Lester ED, Shafaat HS, Obenhuber DC, Ponce A (2007) Bacterial diversity in hyperarid Atacama Desert soils. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 112: G04-S17.

- Ericsson AC, Personett AR, Grobman ME, Rindt H, Reinero CR (2016) Composition and predicted metabolic capacity of upper and lower airway microbiota of healthy dogs in relation to the fecal microbiota. PLoS ONE 11: e0154646.

- Janssen PH (2006) Identifying the dominant soil bacterial taxa in libraries of 16S rRNA and 16S rRNA genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72: 1719-1728.

- Vientós-Plotts AI, Ericsson AC, Rindt H, Grobman ME, Graham A, et al. (2017) Dynamic changes of the respiratory microbiota and its relationship to fecal and blood microbiota in healthy young cats. PLoS ONE 12: e0173818.

- Jurelevicius D, Alvarez VM, Marques JM, de Sousa Lima LRF, Seldin L, et al. (2013) Bacterial community response to petroleum hydrocarbon amendments in freshwater, marine, and hypersaline water-containing microcosms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 79: 5927-5935.

- Kostka JE, Prakash O, Overholt WA, Green SJ, Freyer G, et al. (2011) Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria and the bacterial community response in Gulf of Mexico beach sands impacted by the deep water horizon oil spill. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77: 7962-7974.

- Ron E, Rosenberg E (2010) Acinetobacter and Alkanindiges. Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Germany.

- Meuser H (2013) Treatment of contaminated land. In: soil remediation and rehabilitation: treatment of contaminated and disturbed land, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp: 127-162.

- Pinhati FR, Del Aguila EM, Tôrres APR, Sousa MP de, Santiago VMJ, et al. (2014) Evaluation of the efficiency of the degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons by bacteria from an oil refinery effluent treatment plant. Química Nova 37: 1269-1274.

- Van Beilen JB, Funhoff EG (2007) Alkane hydroxylases involved in microbial alkane degradation. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 74: 13-21.

- Ghosal D, Dutta A, Chakraborty J, Basu S, Dutta TK (2013) Characterization of the metabolic pathway involved in assimilation of acenaphthene in Acinetobacter sp. strain AGAT-W. Research in Microbiology 164: 155-163.

- AitTayeb L, Ageron E, Grimont F, Grimont PAD (2005) Molecular phylogeny of the genus Pseudomonas based on rpoB sequences and application for the identification of isolates. Research in Microbiology 156: 763-773.

- Fuentes S, Ding GC, Cárdenas F, Smalla K, Seeger M (2015) Assessing environmental drivers of microbial communities in estuarine soils of the Aconcagua River in central Chile. FEMS MicrobiolEcol 91: 110.

- Stallwood B, Shears J, Williams PA, Hughes KA (2005) Low temperature bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil using biostimulation and bioaugmentation with a Pseudomonas sp. from maritime Antarctica. Journal of Applied Microbiology 99: 794-802.

- Das N, Chandran P (2010) Microbial degradation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminants: an overview. Biotechnology Research International 2011: e941810.

- Kadali KK, Simons KL, Skuza PP, Moore RB, Ball AS (2012) A complementary approach to identifying and assessing the remediation potential of hydrocarbon clastic bacteria. Journal of Microbiological Methods 88: 348-355.

- Sun W, Dong Y, Gao P, Fu M, Ta K, et al. (2015) Microbial communities inhabiting oil-contaminated soils from two major oilfields in northern China: Implications for active petroleum-degrading capacity. J Microbiol 53: 371-378.

- Bao M, Pi Y, Wang L, Sun P, Li Y, et al. (2014) Lipopeptide biosurfactant production bacteria Acinetobacter sp. D3-2 and its biodegradation of crude oil. Environ Sci: Processes Impacts 16: 897-903.

- Chen J, Huang PT, Zhang KY, Ding FR (2012) Isolation of biosurfactant producers, optimization and properties of biosurfactant produced by Acinetobacter sp. from petroleum-contaminated soil. Journal of Applied Microbiology 112: 660-671.

- Nie M, Yin X, Ren C, Wang Y, Xu F, et al. (2010) Novel rhamnolipid biosurfactants produced by a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain NY3. BiotechnolAdv 28: 635-643.

- Priji P, Sajith S, Unni KN, Anderson RC, Benjamin S (2017) Pseudomonas sp. BUP6, a novel isolate from malabari goat produces an efficient rhamnolipid type biosurfactant. J Basic Microbiol 57: 21-33.

- Saikia RR, Deka S, Deka M, Banat IM (2012) Isolation of biosurfactant-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa RS29 from oil-contaminated soil and evaluation of different nitrogen sources in biosurfactant production. Ann Microbial 62: 753-763.

- Barkay T, Navon-Venezia S, Ron EZ, Rosenberg E (1999) Enhancement of solubilisation and biodegradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by the bioemulsifieralasan. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 65: 2697-2702.

- Bordoloi NK, Konwar BK (2009) Bacterial biosurfactant in enhancing solubility and metabolism of petroleum hydrocarbons. Journal of Hazardous Materials 170: 495-505.

- Reddy MS, Naresh B, Leela T, Prashanthi M, Madhusudhan NC, et al. (2010) Biodegradation of phenanthrene with biosurfactant production by a new strain of Brevibacillus sp. Bioresource Technology 101: 7980-7983.

- Di Gennaro P, Moreno B, Annoni E, Garcia-Rodriguez S, Bestetti G, et al. (2009) Dynamic changes in bacterial community structure and in naphthalene dioxygenase expression in vermicompost-amended PAH-contaminated soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials 172: 1464-1469.

- García-Díaz C, Ponce-Noyola MT, Esparza-García F, Rivera-Orduña F, Barrera-Cortés J, et al. (2013) PAH removal of high molecular weight by characterized bacterial strains from different organic sources. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 85: 311-322.

- Riser-Roberts E (1992) Bioremediation of petroleum contaminated sites. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, USA.

Relevant Topics

- Anaerobic Biodegradation

- Biodegradable Balloons

- Biodegradable Confetti

- Biodegradable Diapers

- Biodegradable Plastics

- Biodegradable Sunscreen

- Biodegradation

- Bioremediation Bacteria

- Bioremediation Oil Spills

- Bioremediation Plants

- Bioremediation Products

- Ex Situ Bioremediation

- Heavy Metal Bioremediation

- In Situ Bioremediation

- Mycoremediation

- Non Biodegradable

- Phytoremediation

- Sewage Water Treatment

- Soil Bioremediation

- Types of Upwelling

- Waste Degredation

- Xenobiotics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5211

- [From(publication date):

May-2017 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 4249

- PDF downloads : 962