Appearances of Stigma and Discrimination among Immunocompromised Female Injecting Drug Users (Fidu) - A Study in Champai, Mizoram in India

Received: 01-Jul-2021 / Manuscript No. dementia-21-35299 / Editor assigned: 05-Jan-2022 / PreQC No. dementia-21-35299 (PQ) / Reviewed: 18-Jan-2022 / QC No. dementia-21-35299 / Revised: 24-Jan-2022 / Manuscript No. dementia-21-35299 (R) / Accepted Date: 24-Jan-2022 / Published Date: 31-Jan-2022 DOI: 10.4172/dementia.1000117

Abstract

In India the HIV positivity in among IDUs stands at a staggering 7.71. Injecting drug use among female appear to mirror patterns among males, but with greater adverse consequences. They are still a group of population that lacks visibility, and are subjected to multiple layers of stigma because they belong to socially deviant and disenfranchised groups with facing gender-specific inequality and exclusion. The study aimed at understanding the ways in which FIDUs Champai district of Mizoram indigenous minority community, experience stigma and discrimination and the impacts that stigma and discrimination may have on their abilities to access health services. The qualitative study also used content analysis and the health stigma and discrimination framework analysis. The study found several forms of stigma among female injecting drug user that deters their access and utilization of health services and suggested a range of specific gender-specific individual-, social-, and structural-level interventions.

Keywords: Champai, FIDU, PLHIV, stigma, discrimination.

Keywords

Champai; FIDU; PLHIV; stigma; discrimination

Introduction

Injecting drug use is a notable driver of HIV infection globally [1]. In India the HIV positivity in among IDUs stands at a staggering 7.71% [2]. Even though no global estimate of female IDUs exist, but recent study in India estimated female IDUs were 10,055–33,392 in numbers [2]. Injecting drug use among female appear to mirror patterns among males, but with greater adverse consequences. Social adversity, high levels of exposure to substance using families, high rates of sharing and reusing, high rates of involvement in sex work, high levels of stigma and poor social support characterize this group. Sexual and reproductive health problems are frequent, particularly abortions [3]. Even though evidences suggest an increase in the number of Female Injecting Drug Users (FIDUs), they belong to socially deviant and disenfranchised groups with facing gender-specific inequality, stigma and exclusion [4].

This study attempts to focus on FIDUs of Mizoram state’s Champai district, situated at Myanmar border, known for the illegal drug route. Mizoram estimated more than 28 thousand people injecting drugs for non-medical purposes – highest among all states [5]. The HIV prevalence of 19.8% was considered stable to rising epidemic [6]. Heroin addiction among young people of both genders stood at 81.7% and injecting drug use affected 96.2% young males and females of Champai district with 61.2% sharing of injecting paraphernalia reported for the district [7].

Objective

The study was conducted among hard-to-reach female injecting drug users with the view to understanding the impediments to their proper healthcare service uptakes, especially reproductive health care and harm reduction services.

Hypotheses

The study embarked at finding out the antithesis fallout on affected population

i.e. stigmatized persons or groups, as well as their family, friend or healthcare providers. Accordingly, we focused on conceptualizing the study on diseases and identities of HIV.

Method

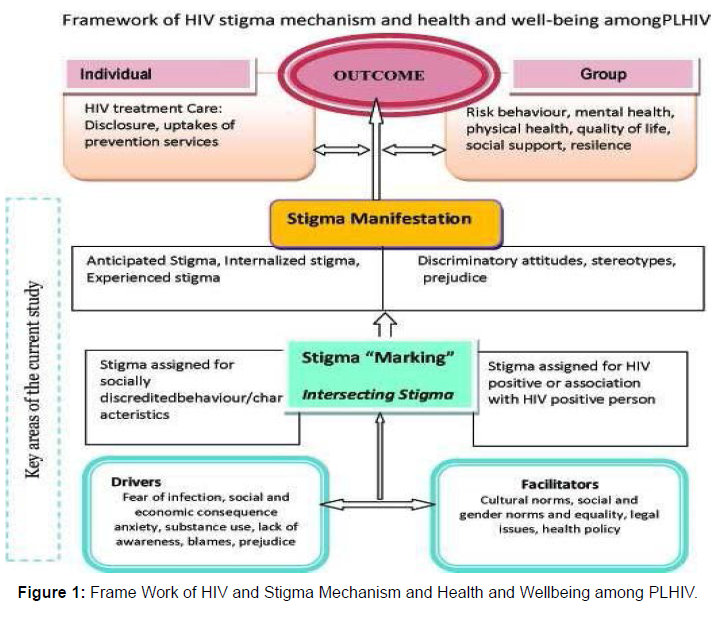

The qualitative study was conducted in August and September 2019 among Female HIV positive intravenous drug users registered in the anti-retroviral therapy centres (ARTC) for more than two years. The data for qualitative study were collected through focus groups with 14 HIV positive FIDUs, conducted in local Mizo twang dialect, were semi-structured consisting of a series of broad open-ended questions. Five individual interviews with ART service providers and Stakeholders were undertaken to obtain their ‘views on FIDUs’ experiences and perspectives. The study used content analysis based on the health stigma and discrimination framework, as proposed by Strangle, Earnshaw, et al [8]. We embarked at finding out the antithesis fallout on affected population i.e. stigmatized persons or groups, as well as their family, friend or healthcare providers. Accordingly, we focused on conceptualizing the study on diseases and identities of HIV, taking cue from the foresaid study, to construct relevant health stigma and discrimination framework for the study, as in Figure 1 below.

Settings: The focus groups were conducted at participants’ convenient location near to New Hope Society- care & support centre organization (CSCO). All the participants were linked to CSCO, but none of reportedly linked to any intravenous drug user (IDU) targeted intervention (TI) and not covered under needle-syringe exchange programme (NSEP), nor were they receiving opioid substitution therapy (OST). However, they received CSCO services as counselling, periodic CD4 count test guide, and referrals, as stated.

Participant selection and recruitment: In the current study a person who has injected at least once in the last three months is categorized as an IDU in keeping with the definition followed in the National AIDS Control Programme (NACO). She should be above 18 years of age and give consent to participate.

Sampling: Given the hidden nature of FIDUs, we attempted snowball sampling to recruit participants for the study. Altogether 18 FIDUs were approached at the ARTC among whom 2 females declined to participate stating time constraints. Only 14 females consented to participate in the 2 focus groups organized. 5 Key Informants including ARTC Doctor, Nurse, Counsellor and 2 CSC functionaries participated in the Individual interviews.

Data Collection & Analysis: Data Collection & Analysis: Thematic content analysis with some elements of grounded theory was used to analyse the data. All individual interviews were conducted either in Mizotwang or English according to convenience of respondents. Focus Groups Discussion (FGD) was conducted in Miso twang language and each focus group lasted between 60-75 minutes. A summary of sociodemographic with drug use and HIV positive status was generated using Microsoft Excel systems. Discussion was noted verbatim by two note takers holding knowledge of the languages and verbatim responses capturing methodologies. Two separate transcripts were prepared and tallied for consistency. Emerging themes were identified as being ‘chief’ if they were common across sources. Transcripts were analysed through QAD MINAR software and codes were generated. Recurrent themes were identified with further examination of data for nuances, similarities, and differences through constant comparison approach done [9]. Final codes were categorized to generate themes related to women’s experiences of stigma and its impact on their access to health services. The socio-demographic profile of participants (n= 14) and years are summarized in Table 1 below.

| Characteristics Women (n=14) | N value |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20-35 years | 78.6 |

| Above 35 years | 21.4 |

| Education | |

| College level | 28.6 |

| High School level | 50 |

| Primary | 21.4 |

| Illiterate | 0 |

| Employment status | |

| Service | 14.3 |

| Business | 35.7 |

| Housewife | 0 |

| Without formal job | 7.1 |

| Unemployed | 42.9 |

| Income/ No income | 42.9 |

| Below 5000- | 7.1 |

| 5000-10000- | 42.9 |

| Above 10000 | 7.1 |

| Mean Income | 5250 |

| Marital status | 28.6 |

| Single | 21.4 |

| Married | 7.1 |

| Widow | 35.7 |

| SeperatedSingle | 7.1 |

| Substance use status | |

| Oral & Chasing – | 0 |

| Heroin & Ors – | 100 |

| Frequency | Daily (100.0) |

| Injecting drug use | Heroin (100.0) |

| Frequency | |

| Weekly | 50 |

| Monthly | 50 |

| HIV treatment status | |

| Registered with ARTC | |

| 2-5 years | 71.4 |

| Above 5 years | 28.6 |

| Adherence in the last 12 months Above 95% - | 0 |

| 90 – 95%- | 50 |

| 80% and below | 50 |

Table 1: Sociodemographic profile with substance use history & art status of participants.

Results

The study identified major forms of stigma as- Anticipated Stigma, Internalized Stigma and Experienced Stigma based on interface with respondents as enumerated hereunder.

Anticipated Stigma among FIDUs reflects their expectations of stereotyping, prejudice, and/or discrimination. Most of the participants stated that human interaction begins to be framed within the context of HIV, and becomes the overriding perspective when dealing with others. According to FGD participant 1 ‘As a HIV positive female, I become very sensitive to what people say and how they treat me. I feel ‘en dawn (looked down upon)’. Another FGD participant 4 pointed out “I think especially for women doing IDU, it’s hard because we’re expected to be a play mother’s roles, take care of everything, always look good, always be happy and not care for ourselves as much as we care for everyone else. While this narrative illustrates perception of female drug users’ greater stigmatization based on traditional family norms, it also suggests a complex and contradictory power dynamic at play in gender role norms, particularly for women. Participants account suggested that women perceived a unique stigma of drug use, because injecting drug use ran contrary to gender norms of behaviour. The ARTC counsellor commenting on the prevalent negative perception of FIDUs said, ’most people feel it is a shame for a woman to be an injecting drug user’.

Most of the participants tend to perceive discrimination in general healthcare settings for FIDUs, as segregation practices intentionally used to differentiate people living with HIV (PLHIV) from the general care population. One FGD participant 6 informed ‘my friend was referred to gynaecologist in the hospital for her STI problems that didn’t subside with presumptive treatment at ART centre. The doctor at the hospital noticed her ARTC green booklet (patient treatment history book) pulled his chair back and hurriedly jotted down some medicine and asked her to leave without explaining her anything”. Some participants shared that there was a recent reduction in discriminatory attitudes and behaviour in HIV health care settings, as they said ‘HIV/AIDS specialists treated us normally and quite helpful to PLHIV without being judgmental toward IDUSs’.

Internalized stigma- participants’ account indicated a self-directed shameful consciousness of being an injecting drug user female and PLHIV. Internalization of stigma was often associated with low selfesteem among participants as- ‘it is difficult to tell others of my HIV positive status, being IDU’ – FGD participant 2 stated. ‘I feel worthless being IDU and also as HIV positive’ – another FGD participant 13 added. Both the statements carry participant’s negative reflection about self in varying degrees. Self-stigmatization resulted from study participants internalizing the negative perception of injecting drug use within the study setting, where drug use was generally construed as resulting from a failure of individual morality. FIDUs were commonly referred as ’hmeichhia ruihhlo ngai’ (female drug user) and they are often thought of as ‘K.S.’ (slang word for female sex workers). Not surprisingly, FIDUs found such identities shameful and they had an interest in concealing their stigmatized identities. As FGD respondent 8 said, ‘I usually don’t like people to know my drug injecting status because I feel shame and when going out invariably use body covered clothes to hide injection marks’.

Experienced stigma- Many participants stated to have experienced negative attitude towards injecting drug user from their communities. ‘When I started doing drugs and injecting, others who do not use, refused to mix with me. I was able only to associate only with fellow drug users’ – informed FGD participant 5. Two other FGD respondents also stated they were also stigmatized by some of their family members: ‘From my own perspective, even the CSC workers are more concerned with us and love us even more than our relatives’- respondent 9 stated. And respondent 11 added, ‘If you try to reason out or explain something in the family settings, they brush you aside as an addict. It pains. “Among the participants 42% females were earning either from petty business or in some job. Stigma and discrimination at workplace seemed experienced by some. Said FGD participant 12, a 28 years old single female, ‘I was working in a beauty parlour. Once my HIV positive status became known to the owner, he instructed that I leave the job in the interest of the parlor and find engagement somewhere. I felt devoted’. Participants described how this stigma was invoked within a milieu of social dynamics and moralistic attitudes, conveying a notion of moral judgments and suspicion: ‘People stated to me that a ruihhlo ngai (drug user) is a sinner’- FGD respondent 14 stated. Another respondent 7, informed, ‘My school-day friends and neighbors become unduly alarmed by my presence near to their houses, as if I am thief. Very demeaning for Me.’Apart from experiencing stigma and discrimination in public spaces, FIDUs frequently experienced the same in healthcare related settings. Respondent 10 reported ‘health care staff at the centre have a queer look at us, and whisper among fellow staff on my doing drugs and injecting habits’. Some participants also lamented over their non-existed access to needle syringe exchange programme and opioid substitution therapy under the IDU TIs.

Stigma of being FIDU was layered over HIV-related stigma, as respondent 11 described preceding HIV stigma, even from their fellow drug users. According to FGD respondent 3, ‘Once I was detected HIV positive through community based testing; my fellow drug user asked me not to come in their group’. This statement suggested that being HIV positive was different source of shame among women who inject drugs.

Given these deeply ingrained cultural beliefs and taboos, coping with multi- layered stigma is particularly challenging for females. Despite this, PLHIV FIDUs found to hold positive internal beliefs about themselves as- ‘I have changed over the years. It’s like, I don’t care who knows, everybody can know,’ respondent 9, a 36 years old lady, a separated from marriage and in a government, on ART for the last seven years asserted. Still another respondent-13, a 26 years old single lady, with college level education, on ART regimen for 5 years and doing petty business, stated- ‘I have understood that worrying won’t help. I take my ART medicines regularly and keep going.’

Negative impact of stigma- Notwithstanding the source, stigmatization of women seemed to result in isolation and exclusion through prejudiced social processes and institutional practices. Responding to a question about the impact of stigma, one participant described how relatives and associates ‘abandon and stay away’ FGD respondent 1 said. Another FGD respondent 5 opined that ‘people cannot agree to be with someone who is chasing or injecting drugs.’ Notwithstanding social isolation, our data suggested that enactment of stigma – overt discrimination- served as a distinctive barrier to health service access. Participants characterized the actions of health system functionaries ‘disdainful maltreatment’ as FGD respondent 2 commented. Another FGD respondent 7 stated, ‘Should they know that one is an addict, they send the patient backward on the queue or tell the person to go and come later’.

Apart from the negative perception of drug use, CSC functionary pointed out- ‘the health care workers did not understand why and how they need to serve female drug users. Nevertheless, given women’s experiences, being stigmatized at health facilities meant that ‘she had never gone back’ he added. But, studies indicated that many women inevitably found themselves compelled by circumstances to seek health services, and in those situations, they strived to conceal their identities, so as to avoid being stigmatized or discriminated against [11]. In Champai many participants opted to be accompanied by CSC outreach workers to the health centers, to avoid being feeling embarrassed. One FGD respondent-4 claimed, ‘if we go to hospital with the out-reach workers (ORW), the health providers give us the required services without asking many question’

Discussion

In review of relevant documents and published research articles, the study endeavoured at analysing the various forms of stigma and discrimination faced by PLHIV FIDUs of Champai on the conceptualized stigma framework as in figure-1, to understand the stigma drivers and facilitators. Interactions with key informants indicated that lack of public awareness and knowledge on HIV issues concerning intravenous drug use, especially by females, existed, as the CSCO functionary said “intravenous drug use is considered as synonymous with HIV paying no heed to the fact that injecting drugs, per se, does not spread HIV; it is the sharing infected injecting equipment that does so. IDUs in the region were unfortunately subjected to a high level of stigma and discrimination, and unsubstantiated fear of infection existed as, FIDUs are blamed mostly for the infection”. He also asserted - “Drug use was, rather, looked at as a fashion and a fad of the young in the region. The unfortunate rise of such stigma on the IDUs made them hides their habit. They stopped accessing the services provided for their safety and wellbeing”.

Notably, high literacy rate among females in Mizoram is recorded and all FIDUs participants at Champai held minimum of middle school education. Sharing of injecting paraphernalia by females with their male partner or spouse and unprotected sex were reportedly the dual modes of HIV transmission among FIDUs. In Champai, males continue to be main earning members for the family; and as such females have minimum say in economic matters, in decision making and obviously weak negotiating capacities in conjugal life. Again, among sensitized females, indulging in risky behavior under influence of drugs with male IDUs and partners found common, since IDU is considered by them ‘enjoyable group activity’. Said the ARTC counsellor, “Females are discriminated within the husband’s family if both of them held HIV positive status. Females are often blamed for the death of her husband/ male partner, even if the male had been diagnosed HIV positive earlier. Females reuse needles and injecting equipment with their male partners,” she added.

In the socio-cultural domain, drug use in Mizoram existed since long and casual sex has never been a taboo in some tribal culture. Many of the women drug users grew up in single parent households, experiencing an unstable and unhappy childhood [10]. Champai’s geographical location reportedly gave rise to drug trafficking and human trafficking with Chins tribe people of Myanmar, stereotyped as drug peddlers and traffickers, fleeing and residing permanently in Champhai district mostly [10]. The strong sense of community among the people in the North- eastern states has its negative aspects: drug users, people living with HIV/AIDS and especially female drug users, and their immediate families are often the target of fierce discrimination [10]. The numerous ethnic communities are affiliated to social and religious organizations such as Young Miso Association and Churches of northeast; but these institutions plagued by incomplete and incorrect information on drug use and HIV and holding narrow moral angle, too acted as a major source of stigma and discrimination. The CSC functionary stated, “Easy availability of illegal heroin pushed young people to opioid use and also the sudden surge in wealth and property, which is attributed to profits made from smuggling the precursors, and stress arising out lack of suitable employment opportunities educated youth in the region were contributing factors”. Also, he pointed out, “Many of females into drugs also act as conduit for drug peddling and peer influence push them into IV drug use”. An ARTC service provider stated “for FIDUs, treatment options through drug de-addiction and due coverage under targeted intervention programmes not existed. FIDUs are reluctant to go to oral substitution clinics attended by men; hence many female users stay out of reach of treatment facilities”. According to CSC functionary “gender bias against FIDUs and more so against PLHIV FIDUs in general healthcare settings, barring ART centre, in Champai often compel FIDUs, requiring specialized treatment for certain ailments, suffer.

Drug possession and peddling in Mizoram, is punishable offence and repeated case of Police arrests reported. Stringent law enforcement against heroin trafficking and peddling, in the early 1990s, resulted in shift towards the vein puncturing habit of injecting heroin and other pharmaceutical products. In the perspectives of the above drivers and facilitators, stigma ‘marking’, intersecting with socially discredited behaviour/characteristics on one side and HIV positive status identification and association with persons living with HIV (PLHIV) on the other hand was evident. These caused the emerging of stigma ‘manifestation’ for PLHIV individual and groups; and FIDUs carry the multiple layers of stigmatization i.e. gender norms, injecting drug use and HIV infection. The study thus found several forms of stigma, as stigma of being a drug user, gender-related stigma of being female injecting drug user, and stigma of being PLHIV.

In the perspectives of the above it is important to address different forms of stigma to mitigate their negative impacts on women’s ability to access health services at individual, social and structural levels. At individual level, interventions that support reversal of internalized stigma are required. Research among stigmatized populations has shown that peer-based support approaches can assist in coping and confronting self and external stigma, by harnessing collective self- efficacy, and providing an environment to revamp self-esteem [12,13]. At the social level, it is essential to address moralistic judgements and attitudes that reinforce conservative, but often inequitable stigmatization of women. Working with community group functionaries and religious leaders and initiating community- based advocacy and outreach has shown to soften hard community stances and to reduce discrimination against drug users in Vietnam [14]. Thus, community sensitization can be successful approach adoptable.

At the structural level, interventions for eliminating stigma through proper sensitization of healthcare providers and zero discrimination rules enforced, given the fact that rising number of FIDUs would require health service access [15]. Training on globally recommended comprehensive package of harm reduction services need to be imparted [16]. In addition, peer navigation to health facilities would reduce experiences of stigma and discrimination among FIDUs. The current harm reduction programme, supported by NACO across states, required to refocused with inclusion of effective community and socially oriented harm reduction interventions in mitigating stigma, as it provides an avenue to strengthen employment, livelihood and skills development [16], progressive policing [17], legal support and violence mitigation with a rights-based approach [18,19,20].

In the current study, we embarked at understanding the stigma and discrimination issues concerning female injecting drug users based on the on the conceptualized stigma framework. This framework facilitated in analysing the social and structural pathways in addition to individual pathways. We observed that the stigmatization process unfolds across the socio-ecological spectrum and varies across economic contexts in low-, middle- and high-income countries [20]. We attempted to study the drivers, facilitators, intersecting stigma and stigma manifestations and observed that drivers and facilitators determine stigma marking through which stigma is applied to people or groups. We posited that stigma manifestations influence a number of outcomes for affected individuals and groups, including social acceptance, access to and uptakes of healthcare services, resilience and advocacy. The use of this framework enabled us to gauge stigma among PLHIV FIDUs in concise and comparable manner; and hopefully may be found suitable for use in future research studies, as well.

Limitations and Future Direction

Our study had certain limitations as it involved participants though registered under antiretroviral therapy regimen, but not availing harm reduction service coverage. They were linked to a care and support organization as such their accounts and experiences of stigma may differ from other women. It is indeed possible that our study may be underestimating the impact of stigma among female injecting drug users of Champai, because our purposively sampled participants were already accessing some psychosocial support and anti-retroviral treatment services.

Conclusions

Without intending to totally understand or cause over simplification of the context and experiences of stigma, it is evident that women who injects drugs in Champai or anywhere in Mizoram often selfstigmatize, face stigma of injecting drug use, and are discriminated. These are deterrent in their accessing and availing of health services. Suggestively, to overcome the multiple forms of stigma simultaneously experienced by participants in this study and ensure that tailored gender-sensitive interventions are available to them, a range of specific individual-, social-, and structural-level interventions will need to be implemented. For these to auger, necessary review of National Policy Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 2012, to enable suitable inter-ministerial coordination on provision of addiction treatment under the Union Ministry of Social Justice, as well as access to Harm Reduction interventions and sexual health under Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare are equally meted to female injecting drug users with suitable facilitation at state levels.

Acknowledgment

The study team acknowledges with thanks the support received from Participants and Healthcare Service Providers of Champai for their spontaneous and meaningful interactions. The authors are grateful for the help received from the Mizoram State AIDS Control Society, Champai District AIDS Prevention Control Unit, New Hope Society, and Champai for facilitating the study. Copyright: The manuscript has not been published in any Journal either a Research Paper and/or Conference Paper presentation. Authors do hereby grant Romanian Journal of Psychological Studies licensee to publish their work should it be considered for the same through the review process. Submission of a manuscript implies that the work described has not except in the form of an abstract or as part of a published lecture, been published before (or thesis) and it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere; that when the manuscript is accepted for publication, the authors agree to automatic transfer of the copyright to the publisher.

Disclosure statement

Ethical approval- The study had the approval of Mizoram State AIDS Control Society authority vide No. 11019/1/11/CMO (CPI)/ DAPCU 2652 Dated 23.09.2019

Conflict of interest – Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding- This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial entity or not-for-profit organization.

References

- Stangl L Anne , Earnshaw A Valerie, Logie H Carmen, Brakel van Wim, et al.(2019) The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting, framework to inform research, and policy on health-related stigma. BMC Med 17:31

- Silverman D (2001) Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for Analyzing Talk. Text and Interaction. Forum Qual Soc Res 2:3

- Mburu Gitau, Ram Mala, Skovdal Morten, Bitira David, Hodgson Ian, et al (2013) Resisting and challenging stigma in Uganda: the role of support groups of people living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc 16:18636

- Cornish Flora, Priego-Hernandez Jacqueline, Campbell Catherine, Mburu Gitau, McLean Susie (2014) The impact of community mobilisation on HIV prevention in middle and low income countries: a systematic review and critique. AIDS Behav 18:2110–2134

- Zamudio-Haas Sophia, Mahenge Bathsheba, Saleem Haneefa, Mbwambo Jessie, Lambdin H Barrot (2016) Generating trust: programmatic strategies to reach women who inject drugs with harm reduction services in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int J Drug Policy 30:43–5

- Ayon Sylvia, Ndimbii James, Jeneby Fatma, Abdulrahman Taib, Mlewa Onesmus, et al (2017) Barriers and facilitators of access to HIV, harm reduction and sexual and reproductive health services by women who inject drugs: role of community-based outreach and drop-in centres. AIDS Care 30(4):480-487

- Bobrova Natalia, Rhodes Tim, Power Robert, Alcorn Ron, Neifeld Elena, et al (2006) Barriers to accessing drug treatment in Russia: a qualitative study among injecting drug users in two cities. Drug Alcohol Depend 82:S57–S63

- CampBinford Meredith , Kahana Y Shoshana, Altice L Frederick. (2010) A Systematic Review of Antiretroviral Adherence Interventions for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs. AIDS Care 22:1305-1313

- Pinkham Sophie, Malinowska-Sempruch Kasia. (2008) Women, harm reduction and HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 16:168-118

- Ngo D Anh, Schmich Lucina, Higgs Peter, Fischer Andrea (2009) Qualitative evaluation of a peer-based needle syringe programme in Vietnam. Int J Drug Policy 20:179-182

- Metsch Lisa, Philbin M Morgan , Parish Carrigan, Shiu Karen , Frimpong A Jemima, et al (2015) HIV testing, care, and treatment among women who use drugs from a global perspective: progress and challenges. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69:S162-S168

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at , Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Ghosh GK, Vanlalhumi (2022) Appearances of Stigma and Discrimination among Immunocompromised Female Injecting Drug Users (Fidu) – A Study in Champai, Mizoram in India. J Dement 6: 117. DOI: 10.4172/dementia.1000117

Copyright: © 2022 Ghosh GK, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Conferences

42nd Global Conference on Nursing Care & Patient Safety

Toronto, CanadaRecommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3510

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Mar 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2975

- PDF downloads: 535