Anterior Vitreous Incarceration after Phacoemulsification Cataract Extraction Imaged with Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography

Received: 22-Sep-2015 / Accepted Date: 25-Oct-2015 / Published Date: 29-Oct-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2476-2075.1000101

Abstract

Background: Anterior vitreous incarceration is a condition in which vitreous prolapses into the anterior chamber and passes through a microscopic wound at an incisional site. The condition can be identified as a vitreous strand leading to the wound site during slit lamp examination. If the vitreous strand penetrates through all the corneal layers on to the extraocular surface it becomes vitreous wick syndrome. Anterior segment imaging with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the iridocorneal angle can provide high definition scans to confirm vitreous incarceration and rule out vitreous wicking. It is important to appropriately diagnose this condition to prevent vision threatening complications.

Case report: A case of anterior vitreous incarceration is presented secondary to phacoemulsification cataract extraction. Anterior segment spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scans were obtained to visualize the vitreous strand extending into the cornea but not to the extraocular surface.

Conclusion:This case demonstrates the application of spectral-domain OCT in visualization of anterior vitreous incarceration secondary to phacoemulsification cataract extraction.

Keywords: Vitreous incarceration; Vitreous prolapse; Vitreous wick syndrome; Pupillary block; Cataract extraction; Phacoemulsification

5976Introduction

Vitreous incarceration is a condition where vitreous is trapped within a wound or incision site. When involving the cornea, vitreous can prolapse into the anterior chamber and pass through a microscopic wound at the location of an incision. A vitreous strand is visible on slit lamp examination and the condition is often associated with a peaked pupil where the vitreous strand contacts the iris. If the vitreous penetrates through all the corneal layers and onto the extraocular surface, a vitreous wick syndrome develops significantly increasing the risk for endophthalmitis [1]. Vitreous incarceration can also cause pupillary block glaucoma, cystoid macular edema, vitreoretinal traction, and corneal decompensation [2,3].

Vitreous wick syndrome has been documented as a cause of delayed onset endophthalmitis. In 1970, Ruiz and Teeters described the condition in eleven patients who presented with delayed-onset endophthalmitis after intracapsular cataract extraction surgery (ICCE) with vitreous prolapse [1]. The protruding vitreous strand prevents the wound from closing and can allow micro-organisms to enter [4]. Anterior vitreous wick syndrome is commonly associated with ICCE but has also been reported in cases of extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE), after posterior capsulotomies, as well as corneal relaxation incisions [1,5-7].

Reported cases of vitreous wick syndrome in ICCE and ECCE have been reported to occur 9 to 30 days after the procedure [1,5]. Posterior vitreous wick syndrome has been reported after vitreo-retinal procedures such as intravitreal injections and tranconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy [8-10]. Due to the increased risk for endophthalmitis in vitreous wick syndrome, it is important to identify if the vitreous incarceration penetrated through to the extraocular surface.

Phacoemulsification is considered the standard surgical procedure for cataract extraction in developed countries. The procedure uses ultrasound to fragment and emulsify the cataract. The incision in phacoemulsification is smaller than ECCE and has a lower incidence of complications [11]. The smaller incision allows for faster visual rehabilitation and less induced astigmatism [12]. Reports of vitreous wick syndrome and vitreous incarceration have been mostly associated with ICCE and ECCE and parallels the incidence of vitreous loss. The incidence of vitreous incarceration has been reported to be 8% in ICCE [13]. With improved surgical techniques like sutureless clear corneal cataract incisions associated with phacoemulsification, complications such as vitreous loss has decreased significantly along with vitreous incarceration [1-2,5-7,14-16].

Case Report

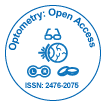

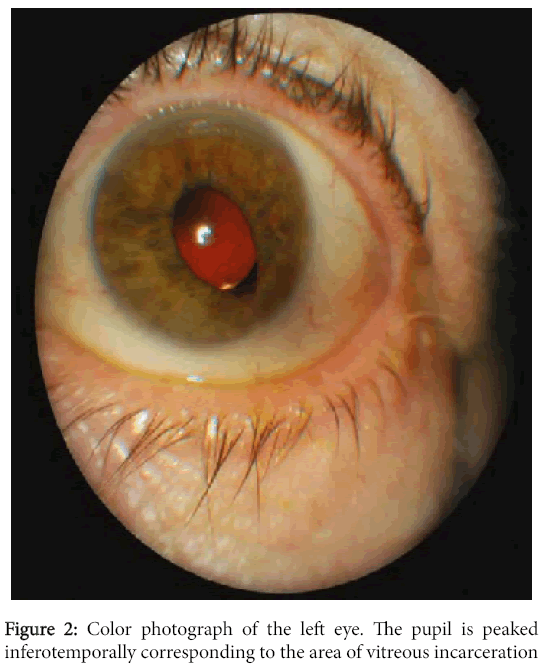

A 72-year-old white male reported for follow up care and refraction after uncomplicated phacoemulsification cataract surgery with posterior chamber intraocular lens implant in his left eye 4 weeks prior. His chief complaint was blurry vision in his left eye (O.S.) at near that was constant. The patient had finished his post-operative ocular medications, which included moxifloxacin 0.5%, diclofenac 0.5%, and prednisolone acetate 1%. His bestcorrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye (O.D.) and 20/20 O.S. On slit lamp examination, the pupil was peaked at the inferotemporal position O.S. and a vitreous strand was visible that connected the posterior chamber to the anterior cornea at the location of the incision site. There was a negative Seidel test and no visible external vitreous strand over the anterior surface of the wound site. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet with no cell or flare O.U. A 3-mirror gonioscopy lens was used to attempt to visualize the vitreous strand that blocked the view of the inferotemporal iridocorneal angle. The intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg in both eyes with Goldmann tonometry. Dilated examination identified an inferior anterior capsular tear in the location of the vitreous strand O.S. There were no signs of corneal edema, endophthalmitis, cystoid macular edema, vitreoretinal traction, or pupillary block glaucoma. Cirrus spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) V.6.0. (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, California, USA) anterior segment high definition line scans were completed over the area of the vitreous strand (Figure 1). SD-OCT scans revealed the vitreous strand to protrude through the pupillary border, through the anterior chamber, and up to the superficial anterior layers of the cornea at the incisional wound site. The patient was diagnosed with vitreous incarceration without any definitive signs of extraocular surface exposure and referred back to the cataract surgeon. Given no associated complications, the patient was monitored closely without surgical treatment by both the cataract surgeon and a retinal specialist (Figure 2).

Discussion

Vitreous incarceration after intraocular surgery is secondary to an improperly sealed wound leading to aqueous leakage and vitreous prolapse [1]. Early postoperative wound leakage has been reported in sutureless clear corneal cataract incisions after phacoemulsification.

A possible mechanism proposed is an everted flap of the posterior corneal tissue forming a corneal tongue that prevents normal anatomical apposition of the surgical wound edges leading to potential wound incompetence. The corneal tongue consists of an everted triangular flap of posterior corneal stroma, Descemet membrane, and endothelium [17]. An aqueous leak at the wound may even cause the vitreous to prolapse forward if a capsular break occurs, as seen in the case presented [1,17]

Vitreous incarceration can lead to various complications, such as pupillary block glaucoma, cystoid macular edema, vitreoretinal traction, corneal decompensation, and endophthalmitis [2,3].

Pupillary block glaucoma prevents the flow of aqueous into the anterior chamber [18]. In the case presented, SD-OCT allows the visualization of the iridovitreal synchiae between the vitreous strand and the iris. This area corresponds to the location of the peaked pupil seen on slit lamp examination. The case presented had symmetrical, average intraocular pressures with no suspicion for glaucoma. There were poor views of the iridocorneal angle with 3-mirror gonioscopy in the location of the iridovitreal synchiae due to blockage from the vitreous strand. SD-OCT allowed visualization of the inferotemporal angle and all the structures behind the vitreous strand that were not seen on gonioscopy.

Cystoid macular edema (CME) after cataract extraction, also referred to as Irvine-Gass syndrome, can be associated with complicated cataract surgery. Patients with vitreous incarceration have a higher risk for CME. The exact mechanism is unknown but a proposed theory suggests that tractional forces can attribute to perifoveal permeability [19]. The case presented did not have CME. These tractional forces can also cause vitreoretinal traction leading to higher risk for retinal tears and detachments [3]. Corneal decompensation can occur due to damage of the corneal endothelium from the direct interaction with the vitreous strands [2,3]. Histopathology studies of eyes with vitreous incarceration have demonstrated migration of corneal endothelium onto the adherent vitreous with production of basement membrane (descemetization) [3]. SD-OCT of the case presented, revealed thickening of the posterior corneal stroma and hyper-reflectivity around the area of the cornea-tovitreous strand contact. Increased risk for endophthalmitis occurs when the vitreous strand protrudes onto the extraocular surface forming a vitreous wick. Vitreous wick can be distinguished from vitreous incarceration by completing the Seidel test and gently tugging on the exposed vitreous in the area of the incisional wound site. A positive Seidel test would indicate an aqueous leak and exposure of the vitreous strand. Gently tugging on the exposed vitreous can cause pupillary distortion and movement of the vitreous strand in the anterior chamber [1]. The case presented had a negative Seidel and did not have any exposed vitreous visible on slit lamp examination. By utilizing anterior segment SD-OCT, the vitreous strand could be localized to the anterior corneal stroma with an intact epithelium. Management of vitreous incarceration includes neodymium-doped yttrium-aluminum- garnet (Nd:YAG) vitreolysis, pars plana vitrectomy, anterior vitrectomy, or close monitoring. Steinert and Wassion reported 29 cases of vitreous incarceration and cystoid macular edema treated with Nd:YAG vitreolysis. Fifty five percent achieved two or more lines of stable visual improvement [20]. In the case presented, the cataract surgeon and a retinal specialist decided to monitor the vitreous incarceration given the lack of associated complications.

Conclusion

Vitreous incarceration occurs secondary to vitreous prolapse to the incisional wound site, such as in the case presented after phacoemulsification complicated by an anterior capsular tear. The condition is associated with vision threatening complications and must be recognized and treated promptly. SD-OCT allows visualization of the vitreous strand and the corneal layers involved to differentiate between vitreous incarceration and vitreous wick syndrome.

References

- Ruiz RS, Teeters VW (1970) The vitreous wick syndrome. A late complication following cataract extraction. Am J Ophthalmol 70: 483-490.

- Zare M, Javadi MA, Einollahi B, Baradaran-Rafii AR, Feizi S, et al. (2009) Risk Factors for Posterior Capsule Rupture and Vitreous Loss during Phacoemulsification. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 4: 208-212.

- McDonnell PJ, De la Cruz ZC, Green WR (1986) Vitreous incarceration complicating cataract surgery. A light and electron microscopic study. Ophthalmology 93: 247-53.

- Joondeph BC, Joondeph HC (1986) Purulent anterior segment endophthalmitis following paracentesis. Surg 17: 91-93.

- Rouw J, Shaver JF (2008) Vitreous wicking syndrome as a complication of extracapsular cataract extraction. 79: 193-196.

- Rice TA, Michels RG (1978) Current surgical management of the vitreous wick syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 85: 656-661.

- Sheets JH, Friedberg JG (1980) Vitreous wick syndrome following discission of the posterior capsule. Arch Ophthalmol 98: 327.

- Moshfeghi DM, Kaiser PK, Scott IU, Sears JE, Benz M, et al. (2003) Acute endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection.Am J Ophthalmol 136: 791-796.

- Sommerville DN, Hainsworth DP (2008) Bacterial endophthalmitis following 25-gauge transconjunctivalsuturelessvitrectomy. ClinOphthalmol 2: 935-936.

- Venkatesh P, Verma L, Tewari H (2002) Posterior vitreous wick syndrome: a potential cause of endophthalmitis following vitreo-retinal surgery. Med Hypotheses 58: 513-515.

- Devgan U (2007) Surgical techniques in phacoemulsification. CurrOpinOphthalmol 18: 19-22.

- SteinertRF, Brint SF, White SM, Fine IH (1991) Astigmatism after small incision cataract surgery. A prospective, randomized, multicenter comparison of 4- and 6.5-mm incisions. Ophthalmology98:417-23.

- Irvine SR (1953) A newly defined vitreous syndrome following cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 36: 599-619.

- Syam PP, Eleftheriadis H, Casswell AG, Brittain GP, McLeod BK, et al. (2004) Clinical outcome following cataract surgery in very elderly patients. Eye (Lond) 18: 59-62.

- Lum F, Schein O, Schachat AP, Abbott RL, Hoskins HD Jr, et al. (2000) Initial two years of experience with the AAO National Eyecare Outcomes Network (NEON) cataract surgery database. Ophthalmology 107: 691-697.

- Narendran N, Jaycock P, Johnston RL, Taylor H, Adams M, et al. (2009) The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55,567 operations: risk stratification for posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss. Eye (Lond) 23: 31-37.

- Tam DY, Vagefi MR, Naseri A (2007) The clear corneal tongue: a mechanism for wound incompetence after phacoemulsification. Am J Ophthalmol 143: 526-528.

- Sowka JW (2002) Pupil block glaucoma from traumatic vitreous prolapse in a patient with posterior chamber lens implantation. Optometry 73: 685-693.

- Fisher DH, Schmidt EE (1992) A variance of the vitreous wick syndrome and its relationship to cystoid macular edema. The Southern Journal of Optometry X :11-5.

- Steinert RF1, Wasson PJ (1989) Neodymium:YAG laser anterior vitreolysis for Irvine-Gass cystoid macular edema. J Cataract Refract Surg 15: 304-307.

Citation: Vien L, Yang D (2015) Anterior Vitreous Incarceration after Phacoemulsification Cataract Extraction Imaged with Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography. Optom open access 1: 101. DOI: 10.4172/2476-2075.1000101

Copyright: © 2015 Vien L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 20050

- [From(publication date): 3-2016 - Jul 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 19107

- PDF downloads: 943