Case Report Open Access

An Atypical Initial Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma as Spinal Cord Compression

Swathi Sangli1,3, Pavan Kumar Mankal2*, Evan Fowle4, Jean Abed1, Eileen O’Reilly3 and Donald P. Kotler2

1Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt Hospitals, Icahn School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA

2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt Hospitals, Icahn School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA

3Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

4Department of Pathology, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt Hospitals, Icahn School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Pavan Kumar Mankal

MD, MA, Division of Gastroenterology

Department of Medicine Mount Sinai St. Luke's and Roosevelt

Hospitals Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1000 10th Ave.

New York, NY, 10019, USA

Tel: 212-523-4400

E-mail: pmankal@chpnet.org

Received Date: April 04, 2016; Accepted Date: April 18, 2016; Published Date: April 25, 2016

Citation: Sangli S, Mankal PK, Fowle E, Abed J, O’Reilly E, et al. (2016) An Atypical Initial Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma as Spinal Cord Compression. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 6:416. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000416

Copyright: © 2016 Singli S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

A young male with quiescent hepatitis B presented with sub-acute onset of lower limb weakness found to have an incidental hepatoma that had metastasized to the vertebrae causing an oncologic emergency in the form of spinal cord compression, a rare initial presentation in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Keywords

Hepatitis B; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Hepatoma

Introduction

A young male with quiescent hepatitis B presented with sub-acute onset of lower limb weakness found to have an incidental hepatoma that had metastasized to the vertebrae causing an oncologic emergency in the form of spinal cord compression, a rare initial presentation in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Case Report

A 49 year-old male with congenitally acquired chronic hepatitis B (not on anti-retroviral medications) who emigrated from Ghana 16 years ago, presented with left lower extremity weakness. While visiting Ghana a week prior to his presentation, he developed a progressive, asymmetric, left lower extremity numbness and weakness proximally, which progressed distally. He also complained of epigastric pain radiating to the back bilaterally in a band-like fashion without any gastrointestinal symptoms. He denied fevers, chills, vomiting, jaundice, abdominal distension or genitourinary problems. He had no past surgical history and denied allergies, recent medications use, smoking, or alcohol consumption. His family history was significant for hepatitis B infection for both his parents.

On presentation, his vital signs were within normal limits. The neurological exam was relevant for a profound decrease in strength in his left lower extremity to 2/5 associated with a decreased sensation in both of his lower extremities. He did not have any facial droop, nystagmus, and dysarthria. No cerebellar signs were observed. Proprioception and vibration were minimally present in his toes and Babinski’s sign was negative. The rest of the physical exam was unremarkable. No signs of acute or chronic liver disease were present on exam.

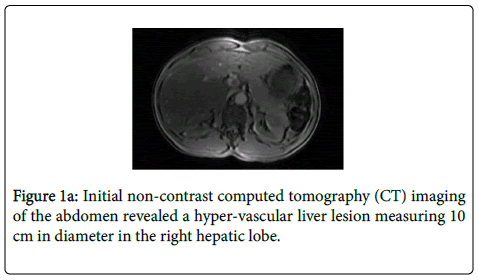

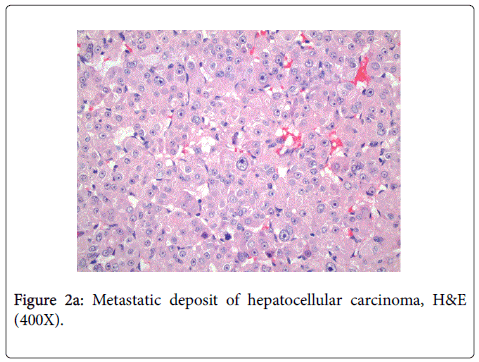

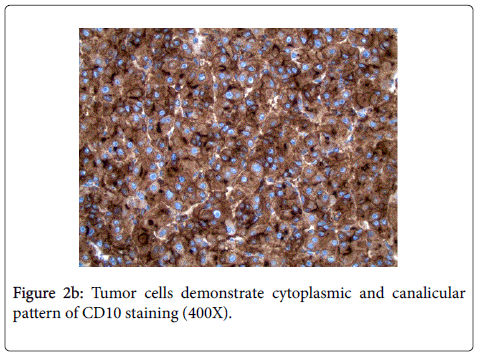

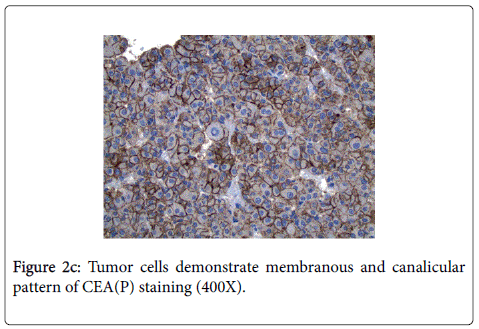

Laboratory findings were notable only for elevated lipase to 2716 U/l and Hepatitis B viral load of 2917 U/mL (Table 1). Initial non-contrast computed tomography (CT) imaging of the abdomen revealed a hyper-vascular liver lesion measuring 10 cm in diameter in the right hepatic lobe (Figure 1a). Human immunodeficiency virus antibody, vitamin B12, and syphilis screen were negative. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were within normal limits, while his AFPL3-isoform was 21.4 ng/mL (0.5-9.9 ng/mL). Further imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen with liver protocol confirmed a 15.0 x 10.9 x 12.8 cm hyper-vascular mass in the right hepatic lobe with a high concern for hepatocellular cancer (Figure 1b). Due to the persistent neurological findings on examination, an MRI of thoracic spine was performed, which demonstrated a large heterogeneously enhancing tumor to the left of the midline at the T7 level measuring approximately 4 cm in the transaxial diameter and extending to the epidural space with spinal cord compression. The patient was promptly started on intravenous steroids and underwent emergent surgical decompression with laminectomy. The patient’s neurological deficits improved significantly, being able to ambulate subsequently. The histology and IHC profile were consistent with metastatic HCC (Figures 2a-2c). Staging the imaging with CT of the chest and abdomen evidenced pulmonary and adrenal metastases. The patient was subsequently referred to oncology and recommended to undergo radiation from T5-T9 to treat residual spinal cord disease and start a trial of sorafenib.

| Test | Value |

|---|---|

| Prothrombin Time | 12.3 seconds |

| Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time | 33 seconds |

| INR | 0.9 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase(AST) | 55 U/L |

| Alanine Aminotransferase(ALT) | 58 U/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 101 U/L |

| Total Bilirubin | 0.4 m/dL |

| Albumin | 3.6 g/dL |

| Platelets | 207 |

| Hepatitis A Ab | Reactive |

| Hepatitis A Ab, IgM | Non-reactive |

| Hepatitis B Surface Ag (HBsAg) | Positive |

| Hepatitis B Core Ab (HBcAb) | Reactive |

| Hepatitis B Surface Ab(HBsAb) | Non-reactive |

| Hepatitis B PCR | 2917 IU/mL |

| Hepatitis B E Antigen (HbeAg) | Non-reactive |

| Hepatitis C Ab | Negative |

| HIV Screen Ab | Non-reactive |

Table 1: Pertinent laboratory tests.

The histopathology from the spinal cord mass showed endotheliallined cords of polygonal epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm.

Highly pleomorphic, centrally-located prominent nucleoli with coarse chromatin were observed. Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were positive for CD10, Hep Par-1, polyclonal CEA, and villin, but were negative for AFP, CK7, CK20, and MOC31.

Discussion

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a malignant tumor with a growing burden in the United States with increasing prevalence; being the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and second highest in terms of mortality, with one million cancer deaths yearly [1]. A myriad of risk factors contribute to HCC, including hepatitis B viral (HBV) infection, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, cirrhosis of any cause, alcohol abuse, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, hereditary hemochromatosis and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. While liver cirrhosis commonly poses risk for liver malignancy in patients, HCC can also occur in non-cirrhotic patients particularly in patients with HBV [2].

Our patient with a quiescent congenital hepatitis B presented with a sub-acute onset of lower limb weakness without symptoms directly attributable to the primary malignancy and was found to have a metastatic HCC with spinal cord compression. In HCC, the most frequently encountered metastatic sites are lungs (47%), lymph nodes (45%), bone (37%), and rarely adrenal glands (12%) [3]. An increased incidence of bone metastases of up to 25% over the last decade involving the axial skeleton frequently has been previously observed [4,5]. While spinal cord compression does occur in patients with advanced HCC, initial presentation of HCC as a spinal cord compression in the setting of HBV is rare [6,7]. In such circumstances, there occurs a gross deflection in the treatment algorithm for patients with advanced HCC.

Management of HCC has evolved to include surgical, radiological and medical approaches. Althoughthe surgical approach is potentially curative, its indication, particularly in patients with small solitary tumors, is not without higher rates of hepatic decompensation [8]. Recently, loco-regional ablative therapies (i.e., radiofrequency ablation, chemo-embolization, Y-90 microspheres) have become popular allowing for greater tolerability, concentrated therapy, and better survival in patients with localized HCC [9-11]. Though other agents are being investigated, sorafenib has demonstrated a 2.8-month survival in patients with advanced HCC with longer time to radiologic progression [12]. This was demonstrated by the SHARP trial in the region with a higher prevalence of those identical to our patient who was a non-cirrhotic with HCC due to Hepatitis B. Spinal cord compression as a complication of metastatic carcinoma requires prompt diagnosis and urgent surgical decompression, which can significantly change the clinical course [13]. Clinical trials have shown that decompressive surgery has shown the best chance for recovery and future ambulation [14].

Given the projected dismal prognosis of those with metastasis, early diagnosis of HCC by routine surveillance in high-risk patients is of paramount importance. Despite constant strives to provide the best surveillance strategies; there are several limitations in the present routine screening process. One of the meta-analysis showed that using ultrasound surveillance alone did not detect up to one-third of early-stage HCC, while combining it with AFP improved detection by an additional 6% [15]. For this reason, identifying sensitive biomarkers, specifically for those with a tendency to become aggressive metastatic tumors, is crucial.

Given its high specificity, AFP has been extensively used as the biomarker of choice in the screening for HCC. However, its sensitivity is low in non-cirrhotic patients. It is also well recognized that there is a significant proportion of hepatocellular carcinoma that is AFP negative. These instances have paved the way for discovering the diagnostic value of novel tumor markers. The broad principle in developing these tumors markers includes screening, potential targeted therapies, diagnostic and prognostic purposes concurrently. With growing evidence for the applications of established novel markers, their expression is being more predictable, effective and thus has further established their potential importance in the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (Tables 2 and 3).

| Tumor marker | Sensitivity [16] | Specificity | Combination with AFP |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFP-L3 | 61.6 | 92 | 73.7 and 83.6 |

| DCP | 72.7 | 90 | 84.8 and 90.2 |

| Osteopontin | 95 | 69 | 98 and 62 [17] |

Table 2: Tumor markers in metastasis.

| Biomarker | Use |

|---|---|

| AFP-L3 | An independent marker from AFP in HCC with a very high specificity [18] |

| Valuable indicator of poor prognosis [19] | |

| DCP | Linked to have superior accuracy as a diagnostic marker than [20] AFP and AFP-L3 in larger metastatic tumors. |

| Osteopontin | Diagnostic and a potential therapeutic marker in metastatic [21] HCC |

| Has a good sensitivity in AFP-negative HCC |

Table 3: Clinical application of biomarkers for metastatic disease.

Based on recent studies, novel tumor markers that hold relevance in metastasis [22] include lensculinaris agglutinin-reactive glycoform of AFP (AFP-L3), osteopontin, des-γ-carboxyprothrombin [23], golgiphosphoprotein, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-B) and hepatocyte growth factor. The sensitivities and specificities of those with further relevance in metastatic cases are noted in Table 2. In our patient, the findings of elevated AFP L3-isoform levels and normal AFP levels prompts the utilization of novel biomarkers to adequately establish a diagnosis in a high risk patient. Understandably, single biomarker in isolation will not necessarily establish diagnosis. There are several studies proposing the use of a score that aggregates various biomarkers given the heterogeneity of tumors. However the absolute relevance of these tumor markers is poorly understood. Tailoring the use of markers in individuals with major risk factors including infection with Hepatitis B virus or Hepatitis C virus in endemic areas (Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa), alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease for early detection will allow improved clinical management of patients. This patient’s uncommon initial presentation with spinal cord compression and Hepatitis B as a major risk factor should lead the clinician to carefully consider HCC in patients presenting with unilateral acute flaccid leg weakness. This case also elucidates the need for future prospective studies to define panels of sensitive biomarkers for improved surveillance of early HCC detection and prevent such oncologic emergencies.

References

- Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB (2004) Hepatitis C infection and the increasing incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 127: 1372-1380.

- El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL (2007) Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 132: 2557-2576.

- Uka K, Aikata H, Takaki S, Shirakawa H, Jeong SC, et al. (2007) Clinical features and prognosis of patients with extrahepatic metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 13: 414-420.

- Fukutomi M, Yokota M, Chuman H, Harada H, Zaitsu Y, et al. (2001) Increased incidence of bone metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 1083-1088.

- Santini D, Pantano F, Riccardi F, Di Costanzo GG, Addeo R, et al. (2014) Natural history of malignant bone disease in hepatocellular carcinoma: final results of a multicenter bone metastasis survey. PLoS One 9: e105268.

- Vargas J, Gowans M, Vandergrift WA, Hope J, Giglio P (2011) Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma with associated spinal cord compression. The American journal of the medical sciences 341: 148-152.

- Nangolo HT, Roberto L, Segamwenge IL, Voigt A, Kidaaga F (2014) Spinal cord compression: an unusual presentation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Pan Afr Med J 19: 363.

- Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, et al. (1996) Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 334: 693-699.

- Lammer J (2010) Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology 33: 41-52.

- Lencioni RA (2003) Small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: randomized comparison of radio-frequency thermal ablation versus percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology 228: 235-240.

- Llovet JM, Bruix J (2003) Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 37: 429-442.

- Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, et al. (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359: 378-390.

- Cho HS, Oh JH, Han I, Kim HS (2009) Survival of patients with skeletal metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical management. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British 91: 1505-1512.

- George R (2008) Interventions for the treatment of metastatic extradural spinal cord compression in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, CD006716.

- Singal A (2009) Meta-analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 30: 37-47.

- Behne T, Copur MS (2012) Biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Hepatol 2: 859076.

- Shang S (2012) Identification of osteopontin as a novel marker for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 55: 483-490.

- Li D, Mallory T, Satomura S (2001) AFP-L3: a new generation of tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta 313: 15-19.

- Okuda H (2010) Clinicopathologic features of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma seropositive for alpha-fetoprotein-L3 and seronegative for des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin in comparison with those seropositive for des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin alone.

- Baek YH, Lee JH, Jang JS, Lee SW, Han JY, et al. (2009) Diagnostic role and correlation with staging systems of PIVKA-II compared with AFP. Hepatogastroenterology 56: 763-767.

- Ye QH (2001) Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning.

- Lopez JB (2005) Recent developments in the first detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Biochem Rev 26: 65-79.

- Fau ZL, Luo FLJ, Luo F (2006) Serum tumor markers for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11269

- [From(publication date):

April-2016 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10437

- PDF downloads : 832