Alemtuzumab Equalizes Short Term Outcomes in High Risk PRA Patients: Long Term Outcomes Suffer

Received: 04-Sep-2017 / Accepted Date: 09-Sep-2017 / Published Date: 13-Sep-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2475-7640.1000117

Abstract

Introduction: Alemtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody used in approximately 13% of kidney transplants, allows for early glucocorticoid withdrawal. High risk patients, defined by a presence of elevated Panel Reactive Antibody (PRA), are at greater risk for rejection, poorer graft outcomes, and have been shown to benefit from induction with alemtuzumab. The aim of this study is to assess the outcomes of immunologically sensitive kidney transplant recipients after induction with alemtuzumab and early steroid withdrawal.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of 668 transplant recipients, all receiving alemtuzumab induction, from March 2006 through November 2015 was performed. High risk patients (defined as elevated PRA >20%) were compared to those with a low PRA (PRA <20%). Outcomes, such as patient survival, graft survival, and rejection were assessed.

Results: Death-censored graft survival at 1-year was greater than 90% for both groups (p=0.343). Graft survival at 3- and 5- years was significantly lower in the high PRA group (3 years: 79.3%, 5 years: 73.2%) compared to the low PRA group (3 years: 91.3%, 5 years: 85.9%) (p=0.003, p=0.013). Overall death-censored graft survival for the high PRA group (77.6%) was also significantly lower than the low PRA group (87.5%, p=0.007). We noted no statistical difference between groups for other negative outcomes such as patient death or delayed graft function.

Conclusion: Alemtuzumab and subsequent steroid withdrawal is effective at reducing short term poor outcome disparities between high PRA and low PRA recipients. However, graft survival after the second year, and increasing rejection rates prior to the fifth year, demonstrates that the short term effectiveness of alemtuzumab does not translate into long term graft maintenance in patients with elevated PRA. This evidence suggests further investigation into the effectiveness of alemtuzumab induction with steroid withdrawal regimens in patients with an elevated PRA.

Keywords: Alemtuzumab; PRA; Immunosuppression

31010Introduction

Alemtuzumab, a lymphocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody that targets CD52 on immune cells, has been used as an induction agent in a significant minority of renal transplants. By binding to CD52, the antibody mediates lysis of lymphocytes through antibodydependent cell-mediated cytolysis, complement-dependent cytolysis, and induction of apoptosis [1]. A perceived advantage to alemtuzumab induction, over other therapies, is the allowance of a steroid-free regimen following transplant. Many studies have highlighted the benefits of early glucocorticoid withdrawal on kidney transplantation outcomes [2-4]. In addition, Alemtuzumab has also demonstrated equal effectiveness in preventing renal graft rejection as conventionally used immunosuppressive induction therapies in high risk patients [5,6].

A subgroup of high risk patients, identified by the presence of Panel Reactive Antibodies (PRA), pose increased risk of additional complications to transplant and graft survival. Risk factors such as blood transfusions, infections, pregnancy, and/ or previous transplants, individually or compounding, have been associated with increased antibody production contributing to an elevated PRA [7,8]. To date, PRA is the only quantitative routinely tested indicator for patient pretransplantation immunoreactivity from a panel of donors. Sensitized individuals (PRA >0%) comprise approximately 30% of the total donor kidney wait list, and there is significant correlation between recipient PRA status and poorer graft survival of multiple organ types, including renal transplantation [9]. Sensitized patients have also been shown to be at greater risk for Delayed Graft Function (DGF), rejection, or not receiving a transplant at all in some instances [10]. Specifically, at a PRA >20%, the risks of sensitization become more evident. Although the implication of elevated PRA and poorer outcomes for kidney transplant recipients is well documented, few have investigated the effect of alemtuzumab on this group of patients. In this study, we compare the outcomes of high-risk and low-risk patients who underwent induction therapy with alemtuzumab and provide interpretation of the results in order to determine a more optimal regimen for high-risk patients.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis on a database of 668 patients who received kidney transplants and were induced with alemtuzumab at the University of Toledo Medical Center in Toledo, Ohio, between March 2006 and November 2015. Donor information included: sex, age, presence of CMV infection, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and donor type. Recipient information included: sex, age, race, serum PRA, type of graft received, and re-transplant status (Table 1).

| Factor | High PRA | Low PRA | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 125 (18.7%) | 543 (81.3%) | |

| Mean age | 50.8 | 52.7 | - |

| Elderly (>65) | 17 (13.6%) | 105 (19.3%) | - |

| Sex (male) | 72 (57.6%) | 170 (31.3%) | ** |

| White | 91 (72.8%) | 384 (70.7%) | - |

| Black | 28 (22.4%) | 122 (22.5%) | - |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.2%) | 27 (5.0%) | - |

| Asian | 2 (1.6%) | 10 (1.8%) | - |

| Mean PRA | 55.8 | 1.6 | ** |

| Retransplant | 56 (44.8%) | 124 (22.8%) | ** |

Table 1: Recipient demographic and general information.

Prior to transplantation, patient profiles were cross-matched for T and B cell status via flow cytometry. Patients with PRA >20% were compared to the remainder of the cohort (low PRA; control). All cases of acute rejection were biopsy-proven.

At the time of the procedure, patients were treated with 25 mg of diphenhydramine intravenously (IV), induction immunosuppression with methylprednisolone 500 mg intravenously (IV) (Solu-Medrol, Pfizer, New York, NY), mycophenolate sodium 540 mg by mouth (PO) (Myfortic, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland), and ALE 30 mg IV was administered.

The post-operative steroid taper consisted of: methylprednisolone 250 mg IV on post-operative day 1, methylprednisolone 125 mg IV on post-operative day 2, prednisone 60 mg PO on post-operative day 3, prednisone 40 mg PO on post-operative day 4, and, finally, prednisone 20 mg PO on post-operative day 5.

Starting on post-operative day 1, Tacrolimus 1.5 mg PO (Prograf, Astellas Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) and mycophenolate sodium 540 mg PO twice per day were given (Novartis, nutley, NJ). Tacrolimus levels were measured and titrated to the correct dose. Side effects permitting, mycophenolate sodium was increased to 720 mg PO at discharge. Steroids were generally tapered to off by one month.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis was started post-operatively with sulfamethoxazole (800 mg)-trimethoprim (160 mg) 1 tab PO (Bactrim DS, AR Scientific, Philadelphia, PA) 3 times per week and clotrimazole troche 10 mg dissolved in the mouth 4 times per day following oral care. Valgancyclovir 450 mg PO (Valcyte, Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was prescribed based on established risk factors.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York). For categorical variables we used Pearson’s Chisquared test. For continuous variables we used independent T-test. Survival curves were calculated using the life table method. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 668 patients underwent kidney transplantation, alemtuzumab induction, and recorded serum PRA profiles. 125 of the 668 patients measured a pretransplant PRA >20%. Baseline characteristics for patients (Table 1) and donor kidneys (Table 2) were stratified according to the PRA level group. Donor characteristics were comparable between groups. The low PRA group had a higher percentage of CMV+ mismatch donors than the high PRA group (p=0.036).

| Factor | High PRA | Low PRA | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean KDPI | 36.7 | 40.7 | 0.121 |

| Deceased donation | 96 (76.8%) | 402 (74%) | 0.57 |

| ECD | 13 (13.7%) | 46 (11.4%) | 0.596 |

| DCD | 87 (90.6%) | 362 (90.0%) | 1 |

| Donor CMV+ | 62 (53%) | 290 (54.4%) | 0.838 |

| Donor race mismatch | 38 (30.4%) | 180 (33.1%) | 0.598 |

Table 2: Donor information.

Recipient demographics between the two groups were similar, as shown in Table 2. The most notable differences were a higher percentage of males and patients undergoing retransplant in the high PRA group (44.8%) compared to low PRA (22.8%). Baseline characters for reasons for renal complications requiring transplantation were also similar for both groups, with the exception of significant difference in the proportion of patients requiring transplantations due to previous graft failure: 9.7% for the high PRA group, 1.7% for the low PRA group. Mean PRA in the high PRA group was 55.8 while the low PRA group was 1.6. The mean recipient age at time of transplant for high PRA and low PRA was 50.8 years and 52.7 years, respectively.

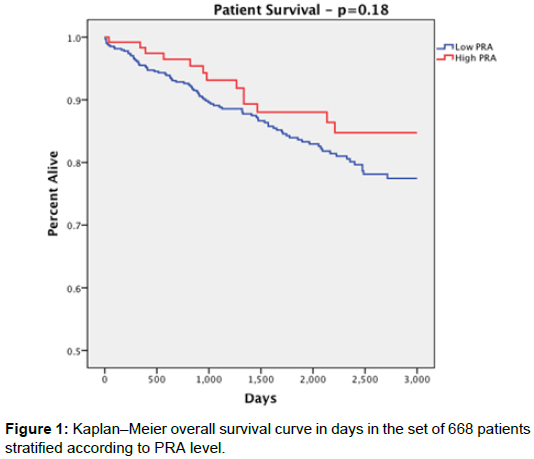

Overall patient survival was 88% for the high PRA group and 83.6% for the low PRA group with no statistically significant difference between them (p=0.274). Patient survival rates at 1 year were 98.2% in the high PRA group and 95.5% in the low PRA group (p=0.286); at 3 years 92.7% high PRA, 89.0% low PRA (p=0.426); at 5 years 87.3% high PRA, 83.4% low PRA (p=0.476), with no significant difference at each time point (Figure 1).

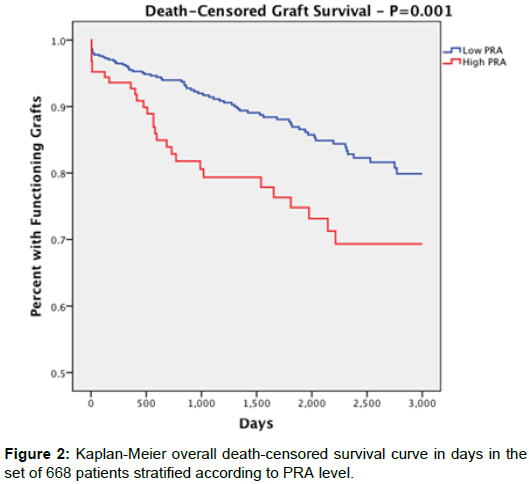

Overall death censored-graft survival (Figure 2) was significantly lower in the high PRA group (77.6%) compared to low PRA (87.5%) (p=0.007). At 1 year, death-censored graft survival presented as 93% in the high PRA group and 95% in the low PRA group with no statistical significance (p=0.343). Death censored-graft survival up to 3 years, however, was 79.3% for the high PRA group and 91.3% for the low PRA group (P=0.003). At 5 years: 73.2% in the high PRA group and 85.9% in the low PRA group (P=0.013).

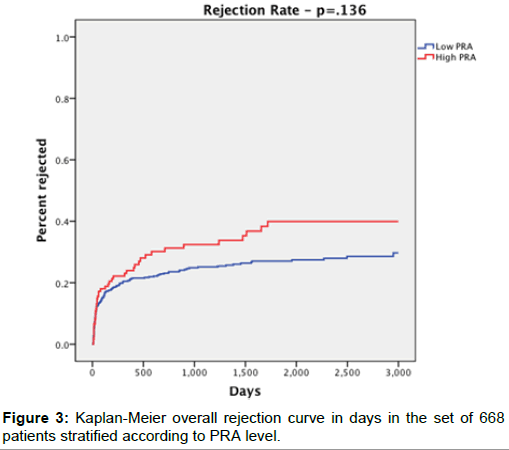

Overall graft rejection survival rates (Figure 3) were 33.6% in the high PRA group and 25.4% in the low PRA group (p=0.073). However, at 1-, 3-, and 5-years, there was no significant difference between groups (p=0.556, p=0.199, p=0.229, respectively).

Graft loss in both groups was primarily due to death and acute rejection, but while loss due to death was 20% and 51.1% in the high PRA group and low PRA group, respectively (p<0.05), loss due to acute rejection was 34.1% in the high PRA group and 10.1% in the low PRA group (p<0.05). These results are shown in Table 3.

| Factor | High PRA | Low PRA | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DGF | 9 (7.4%) | 55 (10.3%) | 0.399 |

| PNF | 2 (1.6%) | 5 (0.9%) | 0.621 |

| Overall Graft Survival (Death Censored) | 97 (77.6%) | 475 (87.5%) | 0.007 |

| -1 year | 106 out of 114 (93%) | 492 out of 516 (95.3%) | 0.343 |

| -3 year | 65 out of 82 (79.3%) | 358 of of 392 (91.3%) | 0.003 |

| -5 year | 52 out of 71 (73.2%) | 269 out of 313 (85.9%) | 0.013 |

| Patient Survival | 110 (88%) | 454 (83.6%) | 0.274 |

| -1 year | 112 out of 114 (98.2%) | 493 out of 516 (95.5%) | 0.286 |

| -3 year | 76 out of 82 (92.7%) | 349 out of 392 (89%) | 0.426 |

| -5 year | 62 out of 71 (87.3%) | 261 out of 313 (83.4%) | 0.476 |

| Rejection Survival | 42 (33.6%) | 138 (25.4%) | 0.073 |

| -1 year | 82 out of 114 (71.9%) | 385 out of 516 (74.6%) | 0.556 |

| -3 year | 50 out of 82 (61%) | 268 out of 392 (68.4%) | 0.199 |

| -5 year | 37 out of 71 (52.1%) | 190 out of 313 (60.7%) | 0.229 |

Table 3: Negative outcomes.

Time (in days) to negative outcomes was also recorded. Of those who experienced a negative outcome, there was no significant difference between the two groups in mean time to graft rejection (high PRA: 336.4, low PRA: 279.9, p=0.466), graft loss (high PRA: 722.5, low PRA: 960.6, p=0.122) and patient death (high PRA: 1329, low PRA: 1067, p=0.533).

Hazard ratio analyses are displayed in Table 4. Age (HR 0.98, CI 0.967-0.994, SI: 0.004), KDPI (HR 1.013 CI 1.005-1.021 SI 0.001), and DGF (HR 2.373, CI 1.488-3.785, SI: 0) were identified as significant factors for rejection in the low PRA group. In the high PRA group, analysis revealed that DGF (HR 2.82, CI: 1.63-4.87, SI:0) was the only significant predictor of rejection. Age and KDPI did not significantly affect rejection hazard for the high PRA group in multivariate analysis. For graft failure: history of rejection (HR 3.76, CI 2.316-6.103, SI: 0), and KDPI (HR 1.021, CI 1.012-1.03, SI: 0) were significant in the low PRA group. In the high PRA group, history of rejection (HR 5.186, CI 1.374-19.576, SI: 0.015) was identified as the strongest predictor of graft failure. For patient death: male gender (HR 1.715, CI 0.999-2.942, SI 0.05), age (HR 1.038, CI 1.016-1.06, SI: 0.001), and Hispanic ethnicity (HR 2.962, CI 1.355-6.473 SI: 0.006) were statistically significant factors for death in the low PRA group. Donor type was identified as the only significant factor for death in the high PRA group; specifically, ECD kidney recipients (HR 8.865, CI 2.697-29.142, SI: 0).

| PRA <20 | PRA <20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Hazard | 9S% a | Sig | Factor | Hazard | 95% a | Sig |

| Age at transplant |

0.98 | 0.967-0.994 | 0.004 | DGF | 2.82 | 1.631-4.874 | 0 |

| DGF history | 2.373 | 1.488-3.785 | 0 | ||||

| KDPI | 1.013 | 1.005-1.021 | 0.001 | ||||

| Graft Failure Final Model | |||||||

| PRA <20 | PRA<20 | ||||||

| Factor | Hazard | 95% a | Sig | Factor | Hazard | 9S% a | Sig |

| Rejection | Rejection | ||||||

| history | 3.76 | 2.316-6.103 | 0 | history | 5.186 | 1.374-19.576 | 0.015 |

| PRA | 1.015 | 1.009-1.022 | 0 | PRA | 1.022 | 1.002-1.042 | 0.034 |

| KOPI | 1.021 | 1.012-1.03 | 0 | ||||

| Death Final Model | |||||||

| PM <20 | PRA<20 | ||||||

| Factor | Hazard | 95% a | Sig | Factor | Hazard | 95% a | Sig |

| Age at transplant |

1.038 | 1.016-1.06 | 0.001 | SCDvsECD | 8.865 | 2.697-29.142 | 0 |

| Male sex | 1.715 | 0.999-2.942 | 0.05 | ||||

| Hispanic | 2.962 | 1.355-6.473 | 0.006 | ||||

| KOPI | 1.013 | 1.004-1.021 | 0.004 | ||||

Table 4: Risk factor Hazard model.

Discussion

Pre-formed antibodies against HLA antigens causing sensitization are well known risk factors for poorer outcomes after kidney transplantation [11-13]. Specifically, acute rejection is a major cause of early graft loss within this population [14]. Even under the immunosuppressive effects of alemtuzumab, we found acute rejection to remain the primary cause of graft loss in the high PRA group. However, patient survival and rejection rates were comparable between our high PRA and low PRA groups with no statistical significant difference. Despite similar poor health risk factor profiles between groups (e.g. recipient BMI, recipient and donor Diabetes status), our high PRA patients had, on average, a significantly longer length of dialysis. These data may suggest the initial efficacy of alemtuzumab in overall rejection, but this is less discernable as other post graft loss protocols play key roles in patient survival rates.

Elevated PRA has also been associated with significantly increased occurrences of graft loss within the first year [15]. We found, however, that 1-year death censored-graft survival was not significantly different between high and low PRA groups and greater than 90% in both. Similarly, Tie-ming et al. found a 90.9% graft survival rate up to 2-years for sensitized patients while using alemtuzumab [16]. Our study expanded beyond two years and found that graft survival rates began to diminish by the third year in the high PRA cohort. The majority of the graft loss occurred after 1-year, with the most obvious marked decreases in graft survival in the high PRA group at 3- and 5-year intervals. Our study was not the first, but correlates with and expands on other studies that suggest that the use of alemtuzumab and subsequent steroid freedom for kidney transplant convey early protective effects, but these effects may not translate to long term graft survival and tend to delay occurrences of acute rejection [17-19]. Overall, alemtuzumab allows for high risk patients to experience a short-term period where their rate of graft loss is equivalent to that of their low risk counterparts. After this honeymoon period, however, the protective effects of alemtuzumab taper and the patient is left at risk. We therefore see the benefits of maintaining these high risk patients on a long-term steroid regimen in attempt to avert an otherwise expedited decline in graft function.

Some studies have demonstrated the potential of immunosuppressive induction therapy to reduce the disparity between negative outcomes of extended versus standard criteria (including deceased vs living) donor kidneys [20-22]. Khalafi-Nezhad et al. found no distinct difference in rejection rates from deceased or living donor kidney recipients [23]. Similarly, we report no significant difference in rejection rates between deceased or living donor kidney recipients in both high and low PRA groups. However, we found donor type to be a significant determinant of time to negative outcomes as opposed to the number of occurrences themselves. Within our high risk group, deceased donor kidney recipients had a significantly shorter time to rejection and rejection survival time when compared to living donor recipients. Interestingly, retransplant patients in our high risk group demonstrated significantly longer graft survival when compared to first time graft recipients within that same group. The same trend was noted for graft survival rate at 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals, although graft survival time and rate were still shorter and lower than low risk, first graft recipients. This trend was not noted for other negative outcomes in retransplant patients. Further study into this phenomenon is required as it may suggest benefit from alemtuzumab for retransplantpatient- specific complications or other outside factors contributing to graft longevity. We must also note a contributing factor could be that patients have been shown to be much more compliant after receiving multiple kidney transplants [24]. In general, these trends support the evidence that alemtuzumab is effective in equalizing some negative outcome disparity in high PRA patients, but other compounding, high risk factors should be considered as they may alter expected outcomes within these groups.

Upon multivariate hazard analysis of the high PRA population in regards to graft rejection, the factors of age at transplant and KDPI do not appear significant. While these two factors were significant predictors of rejection for the low PRA patient group, they were not significant upon univariate analysis for the elevated PRA group (age at transplant: HR 0.99, CI 0.969-1.011, SI 0.356 and KDPI: HR 1.008, CI 0.997-1.02, SI 0.161). Intriguingly, the high PRA group had no significant difference in mean KDPI or age from the general patient population, indicating that there are stronger factors at play for predicting rejection. Multivariate analysis revealed only DGF to be a significant factor contributing to graft rejection in elevated PRA patients. Moreover, in terms of graft failure, a history of rejection was significant in determining failure in both PRA>20 and low PRA groups while KDPI was only significant in the low PRA.

With regards to patient death, there were no overlapping contributing variables to either high risk or low risk groups upon obtaining the multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios. The age at transplant, male sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and KDPI proved significant for the low PRA while only Standard Donor Criteria (SCD) versus Extended Donor Criteria (ECD) proved significant in patients with PRA>20%. Consistent with our other results, SCD versus ECD was the only significant predictor for patient death in the high PRA group (Table 2, p=0.001), even though ECD status proved to be similar and insignificant between both groups. Referring to Table 1, there is no difference in age at transplant, Hispanic ethnicity, nor KDPI, but there was significance in terms of the male sex (p=0). This is significant in that 57.6% of those with a PRA>20% were male while only 31.3% were male in the low PRA group, indicating that being male was a risk factor for having an elevated PRA but was only statistically a risk factor in contributing to death in the low PRA population.

Overall, KDPI taken into consideration with multiple variables seems to be significant in predicting rejection, graft loss, and death only in the general patient population but not in our high PRA cohort.

When comparing patient outcomes between high PRA and low PRA patients, an interesting unrelated trend was observed. Our analysis shows that being of black ethnicity was actually protective in terms of patient death for the control low PRA group (p=0.026) but not for the high PRA group. For the high PRA group, being black played no significant role in patient death, graft loss, or rejection, suggesting that alemtuzumab may equalize some disparities in ethnicity. It is reasonable to assert that alemtuzumab may be a good choice for high risk black transplant recipients. Although, alemtuzumab already has proven its usefulness in this regard in previous study [25,26].

Previous studies have demonstrated the benefits of Alemtuzumab and minimal steroid usage in kidney transplant. However, few have acknowledged the long term consequences of such a protocol within high risk recipient populations. Our research contributes meaningful findings on this matter while concurrently expanding the analysis to include many groups of high risk recipients, including those with elevated PRA. Additionally, with the proportion of highly sensitized patients in our study being comparable to others (18.7%), a respectable sample size was maintained and used for this analysis. Furthermore, uniform pre- and post-operational transplant protocols were used throughout.

While the effectiveness of alemtuzumab in this study shows promising results, there are three main limitations: first, the retrospective nature of this study leads to difficulties in drawing absolute conclusions. Secondly, our sample lacks a direct comparison of other induction methods, including no induction at all, to alemtuzumab. Lastly, as a result of our single center study, these results may not be applicable to all centers.

Conclusion

Alemtuzumab is effective at eliminating the negative outcome disparities between high PRA and low PRA kidney recipients. Patient survival and rejection rates of high risk, high PRA patients were similar to their low PRA counterparts. However, the short-term effectiveness of alemtuzumab in improving graft survival may not directly translate to long-term elimination of this disparity, and require further study of whether this is a result of alemtuzumab itself, or subsequent steroid freedom. Other transplant outcome risk factors, in addition to elevated PRA, also play key roles in determining the efficacy of alemtuzumab in kidney transplantation. This analysis suggests that kidney recipients presenting with elevated PRA in addition to other compounding high risk factors may still benefit from alemtuzumab without complete steroid withdrawal.

Contributors

Stanton, A: Drafting Article/Data interpretation

Naji, M: Drafting Article/Data interpretation

Mitro, G: Statistical analysis

Rees, M: Paper review

Ortiz, J: Study design, paper review and editing

References

- Freedman MS, Kaplan JM, Markovic-Plese S (2013) Insights into the mechanisms of the therapeutic efficacy of alemtuzumab in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Cell Immunol 4: 152.

- Kaufman DB, Joseph R. Leventhal, David Axelrod, Lorenzo G (2005) Alemtuzumab Induction and Prednisoneâ€Free Maintenance Immunotherapy in Kidney Transplantation: Comparison with Basiliximab Induction-Longâ€Term Results. Am J Transplant 10: 2539-2548.

- Matas AJ, Ramcharan T, Paraskevas S, Gillingham J, Dunn DL, et al. (2001) Rapid discontinuation of steroids in living donor kidney transplantation: a pilot study. Am J Transplant 3: 278-283.

- Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, Shihab F, Gaber OS, et al. (2008) A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg 4: 564-577

- Hanaway MJ, E. Woodle S, Mulgaonkar S, Peddi VR, Kaufman DB, et. al. (2011) Alemtuzumab induction in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 20: 1909-1919.

- Shamsaeefar A, Shamsaeefar A, Roozbeh J, Khajerezae S, Nikeghbalian S, et al. (2016) Effects of induction therapy with alemtuzumab versus antithymocyte globulin among highly sensitized kidney transplant candidates. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 4: 665.

- Vaidya S (2004) Synthesis of new and memory HLA antibodies from acute and chronic rejections versus pregnancies and blood transfusions. ‎Transplant Proc 78: 139.

- Dunn TB, Noreen H, Gillingham K, Maurer D, Ozturket OG, et al. (2011) Revisiting traditional risk factors for rejection and graft loss after kidney transplantation. ‎Am J Transplant 10: 2132-2143.

- Smith JD, Danskine AJ, Laylor RM, Rose ML, Yacoub MH (1993) The effect of panel reactive antibodies and the donor specific crossmatch on graft survival after heart and heart-lung transplantation. Transpl Immunol 1: 60-65.

- Bostock IC, Alberú J, Arvizu A, Hernández-Mendez EA, De-Santiagoet A, et al. (2013) Probability of deceased donor kidney transplantation based on% PRA. Transpl Immunol 4: 154-158.

- Cecka M, Zhang Q, Reed E (2005)Preformed cytotoxic antibodies in potential allograft recipients: recent data. Hum Immunol 4: 343-349

- Gebel HM, Bray RA, Nickerson P (2003) Preâ€Transplant Assessment of Donorâ€Reactive, HLAâ€Specific Antibodies in Renal Transplantation: Contraindication vs. Risk. ‎Am J Transplant 12: 1488-1500.

- Zachary AA, Steinberg AG. (1997) Statistical analysis and applications of HLA population data. Manual of Clinical Laboratory Immunology ASM Press Washington DC: 1132-1140.

- Hamed MO, Chen Y, Pasea L, Watson CJ, Torpeyet N, et al. (2015) Early graft loss after kidney transplantation: risk factors and consequences. ‎Am J Transplant 6: 1632-1643.

- Premasathian N, Panorchan K, Vongwiwatana A, Pornpong C, Agadmeck S, et al. (2008) The effect of peak and current serum panel-reactive antibody on graft survival. Transplant Proc 7: 2200-2201.

- Lü TM, et al. (2011) Alemtuzumab induction therapy in highly sensitized kidney transplant recipients. Chin Med J 5: 664-668.

- Sampaio MS, Suphamai B (2009) Alemtuzumab Induction Leads to Better Short-Term Transplant Outcomes, but Long-Term Evidence Needed. Nephrology Times 2 :13-14

- Shapiro R, Basu A, Tan H, Gray E, Kahn A, et al. (2005) Kidney transplantation under minimal immunosuppression after pretransplant lymphoid depletion with Thymoglobulin or Campath. J Am Coll Surg 4: 505-515

- Ciancio G, Burke GW, Gaynor J.J, Carreno MR, Cirocco RE, et al. A randomized trial of three renal transplant induction antibodies: Early comparison of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and steroid dosing, and newer immune-monitoring. Transplantation 4: 457-465.

- De Fijter JW (2001) Increased immunogenicity and cause of graft loss of old donor kidneys. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1538-1546.

- Reutzel-Selke A, Jurisch A, Denecke C, Pascher A, Martins PNA, et al. (2007) Donor age intensifies the early immune response after transplantation. Kidney Int 7: 629-636.

- Hussain SM (2016) Outcomes of Early Steroid Withdrawal in Recipients of Deceased-Donor Expanded Criteria Kidney Transplants in the Era of Induction Therapy. Experimental and clinical transplantation: Official J Middle East Society for Organ Transplant 3: 287-293.

- Khalafi-Nezhad A (2015) Comparison of the Effect of Alemtuzumab versus Standard Immune Induction on Early Kidney Allograft Function in Shiraz Transplant Center. Int J Organ Transplant Med 4: 150.

- Troppmann C, Benedetti E, Gruessner RWG, Payne WD, Sutherland DER, et al. (1995) Retransplantation After Renal Allograft Loss Due to Noncompliance: Indications, Outcome, and Ethical Concerns. Transplantation 4: 467-471.

- Smith A, John MM, Dortonne IS, Paramesh AS, Killackey M, et al. (2015) Racial Disparity in Renal Transplantation: Alemtuzumab the Great Equalizer?. Ann Surg 4: 669-674.

- Brooks J. (2017) Alemtuzumab Induction is Associated with an Equalization of Outcomes. Exp Clin Transplant (Accepted for publication).

Citation: Naji M, Stanton AD, Ekwenna O, Mitro G, Rees M, et al. (2017) Alemtuzumab Equalizes Short Term Outcomes in High Risk PRA Patients: Long Term Outcomes Suffer. J Clin Exp Transplant 2: 117. DOI: 10.4172/2475-7640.1000117

Copyright: © 2017 Naji M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4256

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Nov 21, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3608

- PDF downloads: 648