Editorial Open Access

Advanced Prostate Cancer Survivors: Implications for Palliative Care

Cathy L Campbell1* and Lisa C Campbell21University of Virginia, School of Nursing, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

2East Carolina University, Department of Psychology, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Cathy L Campbell

University of Virginia, School of Nursing

Charlottesville, Virginia, USA

E-mail: clc5t@virginia.edu

Received date: February 04, 2013; Accepted date: April 01, 2013; Published date: April 04, 2013

Citation: Campbell CL, Campbell LC (2013) Advanced Prostate Cancer Survivors: Implications for Palliative Care. J Palliative Care Med S3:003. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.S3-003

Copyright: © 2013 Campbell CL, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Keywords

Questionnaire; Health care providers; Ambulatory care

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in American men. The American Cancer Society (ACS) [1] estimated that 241, 740 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed and 29,720 men will die of prostate cancer in 2013. At this time there are 2.5 million men living with prostate cancer in the United States (U.S.) [1,2]. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that half of all of the living cancer survivors have prostate cancer [3]. Due to advances in screening and treatment for prostate cancer and the relatively slow growth rate of prostate cancer, a large survivor community has arisen [4]. Fewer than 5% of men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer will present in the advanced stages of the disease. However, after the completion of medical and surgical anti-cancer therapies, up to 40% of men will develop advanced metastatic disease [5,6].

Miller et al. [6] proposed the concept “transitional cancer survivor”. A transitional cancer survivor is years past the initial diagnosis and treatment and is living with long-term physical, emotional and psychological sequale related to the treatment or the disease itself (including recurrent disease). Men with advanced cancer of the prostate can be considered transitional cancer survivors because many have complex physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs that extend beyond the active treatment period. Common cancer or treatmentrelated physical symptoms in advanced prostate cancer include bone pain [6], fatigue [6-8], nausea, anorexia, erectile dysfunction, and bladder incontinence [6]. Emotional and psychosocial needs of survivors with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers are also very significant and may not always given the same priority as the physical needs. Important psychosocial needs for patient, intimate partner and other caregivers include support with decision-making [9,10], management of depression and anxiety, emotional support for changes in intimacy and sexual relationships [11-14], and identification of community resources [15,16], financial assistance, and assistance with advance care planning [15-17].

Given the complex needs of men with advanced prostate cancer survivors and their caregivers [4-6,10-16], it is important to know which needs can be met by health care providers and the needs that cannot be addressed in these clinical settings. Identification of these unmet needs can inform the development of interventions to support men with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers and supplement the care that is being provided. This study is guided by three research questions: (1) What are the common needs of men with advanced cancer? (2) Which physical, emotional, spiritual and psychosocial needs of men with advanced cancer and their caregivers can be met by health care providers? (3) Which physical, emotional, spiritual and psychosocial needs of men with advanced cancer and their caregivers cannot be met by health care providers?

Participants and Methods

A survey design was used to identify the needs of men with prostate cancer as identified by health care providers who care for men with advanced prostate cancer. The target group for survey was urological practices in eastern North Carolina and oncology health care providers at two teaching hospitals, one located in eastern North Carolina and the second in central Virginia. Health care professionals who cared for men with advanced prostate cancer were invited to participate in a survey.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Social Sciences at the researchers’ institutions prior to any data collection activities. The participants were invited by e-mail or fax to complete a survey designed to identify the needs salient to patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. We also sent out e-mails to list serves of two cancer centers in the south inviting them to participate in the study. Each participant received a cover letter signed by the researcher, a demographic information sheet, and a survey. The cover letter stated the purpose of the study, length of time to complete the survey, participation was voluntary and that there was no compensation for completing the survey. Further, confidentiality and anonymity were addressed with the following statement, “Because of the nature of the data, it may be possible to deduce your identity; however there will be no attempt to do so and your data will be reported in a way that will not identify you.” The surveys were returned to the research team by fax or computer-generated survey software. We recorded only the number of surveys returned and made no attempt to follow-up on individual surveys with a reminder e-mail, post card, or fax. Each person who completed a survey on-line received a customized e-mail message with a unique Uniform Resource Locator (URL). The customized URL allowed a prospective respondent to pause the survey, save their responses, and return at a later time to resume the survey (using the same or a different computer). This also ensured that they did not complete the survey more than once.

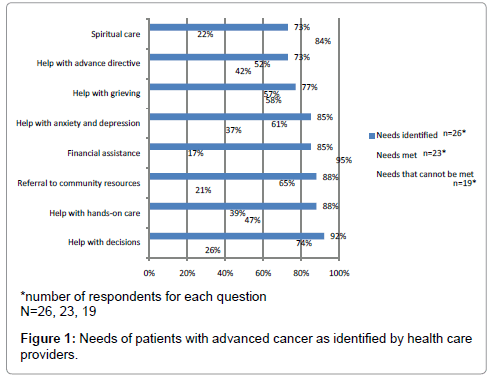

Demographic data were collected with a 6-item survey and 7- item demographic information sheet that included 8 topics related to the needs of men with advanced cancer and their families or caregivers (Survey Questionnaire). The survey was developed for this study by the research team from a review of hospice and palliative care literature about the needs of people with advanced cancer (Figure 1) [15-17]. Three fixed-item questions asked respondents to identify (1) the needs of men with advanced prostate cancer, (2) which of the needs (identified in Question 1) could be met in their clinical setting, and (3) which of the needs identified in (Question 1) could not be met in their clinical setting. Each of the fixed-item questions were followed by fill-in-theblank questions that provided respondents with an option to identify additional patient/family needs and invited the respondent to identify other types of assistance needed by men with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers. The demographic information sheet and survey were designed to be completed in an on-line survey format or by hand with a pencil or pen. The survey was estimated to take 10-15 minutes to complete.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample and analyze the survey, including means for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the cancer-related topics suggested by the respondents that were not included in the questionnaire [18]. Themes were identified, retrieved, and grouped for interpretation of the data.

Results

Table 1 describes the sample characteristics. Thirty providers completed the survey. Mean age of respondent was 46.8 years. The majority of participants reported that their race was White, indicated that they were physicians, and reported that they practiced in outpatient or ambulatory care settings. The respondents mean years in the current clinical role, current clinical setting and experience with people with advanced cancer was 17.8 years, 11.0, and 17.3, respectively.

| Sample characteristics *n=25 ** n=26 ***n=23 | ||

| Age (mean)* Duration in current role (mean)* Duration in clinical setting (mean)* Years of experience with Advanced Cancer (mean)*** Race/ethnicity* |

46.8 17.8 11.0 17.3 Frequency |

Percentage |

| Caucsausian African-American Native American Asian American Hispanic |

20 3 0 1 1 |

80 12 0 4 4 |

| Primary Occupation** | Frequency | Percentage |

| Physician | 18 | 69 |

| Registered nurse | 3 | 12 |

| Nurse practitioner | 1 | 4 |

| Mental health provider | 1 | 4 |

| Other Primary Clinical Setting** Ambulatory care/outpatient Hospital Long-term care Other |

3 16 7 1 1 |

12 61.5 26.9 4 4 |

Table 1: Sample Characteristics.

The survey questionnaire-summarizes needs of patient and families with advanced cancer (common needs of men with advanced cancer identified, needs that can be met in the clinical settings of the respondents, and needs that cannot be met by the respondents). Firstly, respondents were asked to identify the most common need of men with advanced cancer and their caregivers. The needs identified by the respondents (listed from highest to lowest frequency) were help with decisions 92% (24), help hands-on care 88% (23) referral to community resources 88% (23), financial assistance 85% (22), help with anxiety or depression 85% (22), help with grieving 77% (20), and help with an advanced directive 73% (19). The respondents also had the option to identify common needs of advanced prostate cancer patients and their caregivers that were not included in the survey using an openended text field. Qualitative data analysis of the responses in the open-ended text field revealed additional needs of men with advanced prostate and their caregivers, such as pain and symptom management, patient/family education, referrals for other services, hospice-specific information and providing support for the whole family.

Secondly, the respondents were asked to identify needs that could be met in the clinical settings of the respondents. The needs that the respondents selected (from most frequent to least frequent frequency) were help with decisions 74% (17), referral to community resources 65% (15), help with anxiety and depression 61% (14), help with grieving 57% (13), assistance with an advance directive 52% (12), help with hands-on care 39% (9), and financial assistance 17% (4). The respondents were also given the option to use an open-ended text field to identify needs that could be addressed in their clinical settings, but were not included in the survey. Two respondents reported that there were needs that were not listed on the survey that they were able to meet in their clinical settings. The first respondent stated that they were able to provide advice about symptom management, managing medication, and communicating with family and friends. The second respondent wrote that they provided indirect support in making decisions or facilitating a referral to another provider for spiritual care.

Lastly, participants were asked to identify needs that could not be met in the respondent’s clinical setting. Only 63% (19) participants responded to this question. The needs least likely to be addressed were financial assistance.

95% (18), spiritual care 84% (16), and help with grieving 58% (11). Just as in the first and second questions, respondents were invited to write in needs that could not be addressed in their clinical setting. When the responses in the open-ended text field were analyzed two respondents shared needs that that they were not able meet in their practice setting. Help with symptom management was not provided in the clinical setting of the first respondent and the second respondent stated that they did not provide training with hands-on care. Discussion of the study findings, limitations, and implications for research will be presented below.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify, from the clinician perspective, needs salient to patients with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers, which of these needs could be met in the clinic settings of the respondents, and which needs could not be met. We had three major findings: (1) our sample was very experienced in their current clinical roles, clinical settings and in their experience working with people with advanced cancer, (2) consistency between needs identified in the literature and the needs identified as salient to our respondents and (3) health care providers reported a limited capacity to provide emotional, spiritual or financial support, as compared to the list of some needs they could meet. Each of the findings will be discussed below.

As to the first finding, the respondents to our survey were very experienced in their current clinical role, current clinical setting and experience with people with advanced cancer. The gold standard for research is having studies conducted at teaching hospitals or cancer centers. At a teaching hospital or cancer center palliative care services are more likely to be available in the inpatient setting, consultation service or specialty clinic in the ambulatory care setting. However, given the long disease trajectory of prostate cancer, much of the care for men with advanced prostate cancer is occurring in community based practices [19,20].

We found consistency between the common needs of men with advanced prostate cancer identified in the literature and those affirmed by our respondents. For example, the most common need identified in the current study was help with decision-making [9,10]. Men with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers face complex, emotionally-laden decisions, such as beginning, changing or stopping anti-cancer treatment [5,6,10] or considering hospice [9]. Supporting decision making is a significant intervention used by throughout the disease trajectory by all member of the interdisciplinary team, especially the physician [5,6,9,10]. Another important need identified by providers in the current study was referral to community resources. People with advanced cancer and their families require assistance to identify important resources such as financial resources to pay for medication, equipment and supplies, direct hands-on care at home or at a facility within the community [14-17]. The ability to make referral to community resources is an important service that community-based practices can provide.

Relating to the third finding, health care providers were less likely to provide emotional, spiritual or financial support. It is interesting to note that fewer respondents answered the question about the needs that they could not meet in their clinical settings. We know that in busy clinical settings, the focus is on providing medical and nursing care that is needed during the office visit [19,20]. A comprehensive plan of care for a person with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers includes support for psychosocial concerns such as emotional support, spiritual care, assistance with an advanced directive, and financial education [4,16,17,21].

Implications for Palliative Care

Internationally, palliative care interventions have been incorporated throughout the trajectory of a life-threatening illness [22]. In comparison in the United States, the concepts of palliative care and hospice are conflated. Palliative care is described as synonymous with hospice care, and is often used as euphemism to describe all endof- life care. The median length of stay for hospice patients in the US is 19.1 days [23] and 30-35% of people who are admitted to hospice die within seven days or less of admission [23,24].

If a physician or advanced practice nurse applies this narrow interpretation of palliative care to include only those people who meet hospice eligibility criteria [25], transitional cancer survivors with prostate cancer, their intimate partners and caregivers will only have access to clinically significant palliative care interventions for only the last days or weeks of life instead having these important interventions integrated throughout the disease course [17,22]. Hospice care should be included for end-of-life care as an appropriate care transition rather than an intervention introduced during the last days of life.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had several strengths and limitations. To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the palliative care needs of transitional advanced prostate cancer survivors. Secondly, our sample was very experienced in their current clinical roles, clinical settings and in their experience working with people with advanced cancer. The majority of the respondents to the survey were community-based urological providers with a mean of 17.1 years of experience working with patients with advanced cancer. Experienced community-based providers can be a great resource of data about the needs of patients with advanced cancer.

This study had limitations that should be noted. First, given the small sample size, the non-random voluntary-response sampling strategy and lack of data on the number of surveys sent out and the response rate, providers who responded to the survey may not be representative of the population of health care providers for people with advanced prostate cancer. Second, we did not have enough information about the settings so that we could have stratified results by specific types of clinical settings or volume of patients seen in the setting. Respondents who provide care to a large volume of patients/ families may often have more comprehensive services, such as social workers or financial counselors. Third, a self-administered mailed survey was a cost-effective method to collect data from participants across a large geographical area [26,27], but this method of data collection did not provide opportunities for the research team to talk directly with participants to gather additional information about the needs the practice could provide and especially for needs that could not be provided in their practices, such as symptom management and grief counseling.

Given the limitations noted above, future studies should include increasing the sample size to reach a larger pool of health care professionals who provide care to people with advanced cancer, developing mixed-methods studies that allow for direct communication with health care providers, patients and families to explore the needs that are salient to the experience of living with advanced cancer, and identifying associations between the needs identified by patients/ families and health related quality of life (HRQOL).

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify, from the clinician perspective, needs salient to patients with advanced prostate cancer and their caregivers, which of these needs could be met in the clinic settings of the respondents, and which needs could not be met. Two of most common needs identified in the current study were help with decision-making [11,12] and identification of community resources. Of the needs identified community-based physician practices report limited capacity to address the direct physical needs, they may have limited ability to provide emotional, spiritual or financial support that are needed by families. Providing help with emotionally laden decisionmaking such as advance care planning, and the identification of resources are often time consuming for a busy community practice, but these services and more are readily available from an interprofessional palliative care team [17,22]. Given the large and growing number of long-term survivors, the time has come to develop comprehensive plans of care that integrate palliative care principles throughout all phases of the cancer journey [21].

Acknowledgements

Development of the manuscript was supported by 5R01CA122704-04 (Dr. Lisa Campbell) and 3R01CA122704-03S1 NIH/NCI (Dr. Lisa Campbell and Dr. Cathy Campbell).

We would also like to acknowledge Becky Wendland for her work during data collection.

This study was presented as a poster presentation at the Biannual Conference of Region 13, Sigma Theta International, Virginia Beach, Virginia, USA April 20- 21st, 2012.

References

- http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer-key-statistics

- Rivers BM, August EM, Quinn GP, Gwede CK, Pow-Sang JM, et al. (2012) Understanding the psychosocial issues of African American couples surviving prostate cancer. J Cancer Educ 27: 546-558.

- http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/

- Haylock PJ (2010) Advanced cancer: emergence of a new survivor population. Semin Oncol Nurs 26: 144-150.

- Beltran H, Beer TM, Carducci MA, de Bono J, Gleave M, et al. (2011) New therapies for castration-resistant prostate cancer: efficacy and safety. Eur Urol 60: 279-290.

- Miller K, Merry B, Miller J (2008) Seasons of survivorship revisited. Cancer J 14: 369-374.

- Marlow NM, Halpern MT, Pavluck AL, Ward EM, Chen AY (2010) Disparities associated with advanced prostate cancer stage at diagnosis. J Health Care Poor Underserved 21: 112-131.

- Lindqvist O, Rasmussen BH, Widmark A (2008) Experiences of symptoms in men with hormone refractory prostate cancer and skeletal metastases. Eur J Oncol Nurs 12: 283-290.

- Yennurajalingam S, Atkinson B, Masterson J, Hui D, Urbauer D, et al. (2012) The impact of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Palliat Med 15: 20-24.

- Campbell C, Williams I, Orr T (2010) Factors that impact end-of –life decision making in African Americans with advanced cancer. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 12: 214-224.

- Jones R (2012) Decision Making among Patients with Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Southern Nursing Research Society.

- Tanner T, Galbraith M, Hays L (2011) From a woman's perspective: life as a partner of a prostate cancer survivor. J Midwifery Womens Health 56: 154-160.

- Banthia R, Malcarne VL, Varni JW, Ko CM, Sadler GR, et al. (2003) The effects of dyadic strength and coping styles on psychological distress in couples faced with prostate cancer. J Behav Med 26: 31-52.

- Thekkumpurath P, Venkateswaran C, Kumar M, Bennett MI (2008) Screening for psychological distress in palliative care: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 36: 520-528.

- Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Ambrozy DA, Carline JD, Shannon SE, et al. (2003) Dying patients' need for emotional support and personalized care from physicians: perspectives of patients with terminal illness, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 25: 236-246.

- Murray MA, Fiset V, Young S, Kryworuchko J (2009) Where the dying live: a systematic review of determinants of place of end-of-life cancer care. Oncol Nurs Forum 36: 69-77.

- Miller JJ, Frost MH, Rummans TA, Huschka M, Atherton P, et al. (2007) Role of a medical social worker in improving quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention. J Psychosoc Oncol 25: 105-119.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, et al. (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 733-742.

- Miles, M , Huberman, M (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd Ed.). Sage, Thousand Oaks CA

- Smith GF, Toonen TR (2007) Primary care of the patient with cancer. Am Fam Physician 75: 1207-1214.

- Kendall M, Boyd K, Campbell C, Cormie P, Fife S, et al. (2006) How do people with cancer wish to be cared for in primary care? Serial discussion groups of patients and carers. Fam Pract 23: 644-650.

- Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, Debono DJ, Berry SR, et al. (2011) American society of clinical oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 29: 755-760.

- http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Association [NHPCO]. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- Campbell CL, Baernholdt M, Yan G, Hinton ID, Lewis E (2012) Racial/Ethnic Perspectives on the Quality of Hospice Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care.

- http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2004-title42-vol1/content-detail.html

- Curtis EA, Redmond RA (2009) Survey postal questionnaire: optimising response and dealing with non-response. Nurse Res 16: 76-88.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14462

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2013 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9899

- PDF downloads : 4563