Review Article Open Access

Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) Transition into Palliative Care: A Narrative Analysis of Family Member's Stories of Place of Death

Janet Anne Barling*, John Anthony Stevens and Kierrynn Miriam DavisSchool of Health and Human Sciences, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Janet Anne Barling

School of Health and Human Sciences

Southern Cross University, PO Box 157

Lismore, NSW, Australia

E-mail: jan.barling@scu.edu.au

Received date: August 20, 2012; Accepted date: September 25, 2012; Published date: September 27, 2012

Citation: Barling JA, Stevens JA, Davis KM (2012) Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) Transition into Palliative Care: A Narrative Analysis of Family Member’s Stories of Place of Death. J Palliative Care Med 2:130. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000130

Copyright: © 2012 Barling JA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) cancer patients have been described as being orphaned in the system. A major study, investigated the experiences of family members who had an adolescents or young adult who lived with and eventually died of cancer. The participants were a self-selected purposeful sample of 26 family members. Selected methods of narrative analysis were used to create themes in a meta-narrative of the family member’s experience. One of the themes to emerge from the families meta- narrative was the change in the focus of care. Six of the family member’s stories spoke of the palliative care transition. Specific to this was the experience of the transition to place of death with particular reference to dying at home. The results suggest that the transition into palliative should occur sooner rather than later for appropriate supports to be in place to facilitate this transition.

Keywords

Adolescent and young adults; Family members; End of life decisions death and dying; Place of death; Palliative care

Introduction

Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with cancer have been described as being orphaned in the system [1]. This is despite twice as many AYAs being diagnosis with cancer as children [2] and having a higher mortality rate than both children and adults [2,3]. Some factors identified to account for this disadvantage include; medical issues specific to AYAs with cancer, [4,5] delay in diagnosis, [4] fragmented services and lack of access to clinical trials [3,4,6,7] and psychosocial/ life stage issues [3,6]. The fragmentation of services is a result of AYAs being cared for in two systems of care, the paediatric and the adult [8] with different goals and philosophies of care. This has implications not only for medical treatment of AYAs with cancer, but also presents problems in providing targeted support services.

O’Brien et al. [9] identified the following issues that account for the lack of support services. Support services vary across adult hospitals and are fewer than those provided by specialist paediatric hospitals. Support services provided both in paediatric or adult hospitals are not designed for the AYA age group and the lack of critical mass in either system limits the provision of optimal support services. These issues are amplified during the dying stage of the cancer journey. The supported services associated with place of death being of particular significance. This paper presents part of a larger study that interviewed 26 family members who had an AYA live with and die from cancer. The methodology of choice was narrative inquiry with a combination of narrative and qualitative methods to create a metanarrative of commonalities and differences in the experiences of the family members. From the literature the decision of where to die is an important consideration during the dying trajectory. The theme, changing the focus of care was identified from six family member’s stories. This theme suggests that the discussions on place of death should occur early in the transition to palliative care so that support of the AYA and the family is enhanced, regardless of where palliative care is delivered.

Literature Review

Effective and compassionate communication with a child and their family has been associated with high quality, end of life care and the establishment of realistic goals [10]. Further to this, the earlier the child and the family are aware of the terminal nature of the illness the better the integration of palliative care and an improved quality of life [10]. This is also true for AYA’s and their families. Freyer [11] George and Craig [12] George and Hutton [13] and Beale et al. [14] all agree that in order for the dying adolescent to understand and make informed decisions, parents and physicians from the commencement of treatment need to commit to open honest communication with the young person.

This commitment to honest communication has implications for the timing of discussions on the transition into palliative care. For example Wolfe et al. [15] found that the longer the intervals between the discussions of hospice care and death, the more likely the child was to be calm and peaceful during the last month of life. This study suggests that having the opportunity and time to discuss the transition to palliative care results in a more peaceful death.

The ability to engage in discussions about the transition into palliative care results in informed decisions being made regarding the place of death for the AYA. The place of death can occur in: the paediatric or adult hospital, hospice and palliative care, or at home. The place of death has been demonstrated to influence the experience of dying and death for AYAs and their families.

Grinyer and Thomas [16], Bell et al. [17] and Hinds et al. [18] identified the preference for most people with terminal cancer to die in their own home. This is supported by Foreman et al. [19] (Adelaide, Australia) population survey. In this survey the strong preference to die at home was particularly evident for young people.

Grinyer and Thomas [16] used the narrative correspondence method with parents to examine the experience and place of death concerns for thirteen AYAs dying of cancer. In this study two thirds of the young people died at home. The parents wrote of how a home death provided the opportunity to be surrounded by family and friends and to provide a sacred space for the young person to die. Monterosso and Kristjanson [20] noted that parents’ desire to care for the child at home coincided with the need to spend increasing amounts of time with their dying child. Despite this the overall number of cancer patients who die in Atheir home is relatively small [16-19] suggesting that preferences fail to be fulfilled during the terminal phase of the cancer journey.

The fact that preferences to die at home may not be considered, could be a reflection of the curative medical system in which cancer is treated and, as such, carers and patients not being aware of alternative options. Stillion and Papadatou [21] hypothesised that because of the unacceptability of child and adolescent dying, family and medical personnel often fight longer with aggressive treatment for younger people who are dying, and the opportunity to make end of life decisions about where to die can be lost. In support of this Wolfe et al. [15] examined medical records and interviewed 113 parents whose child had died of cancer. The study revealed 80% of the children died of the progression of the cancer and the rest from treatment complications. This study found that most patients received aggressive treatment at the end of life which was associated with substantial suffering, because symptom management was seldom successful. Added to this the parents’ reported the children had little or no fun, were sad, were not calm and peaceful and were often afraid, reflecting a poor quality of life for these children [15]. To alleviate this suffering Hinds et al. [18] believe that accurate diagnosing of when a child or adolescent is dying would provide families with the time to choose a model of care which best suits them. Wolfe et al. [15] further suggest that palliation may need to be incorporated with curative treatment where the likelihood of long-term survival is low.

The wish to die at home was not always possible, for other reasons, as Zelcer et al. [22] discovered in their focus group interviews with 25 parents of 17 children who had died of a brain tumour. Despite wanting to die at home there were barriers to achieving this outcome, which included an inability to manage the symptoms at home, the financial and practical hardships and whether or not there was adequate support within the community.

Hudson’s, [23] Australian exploratory study with primary family carers of 47 advanced cancer patients with a mean age 60, two thirds of whom were female, identified similar challenges. Findings revealed the carer’s ill health, lack of skills to manage the symptoms, lack of support from health care professionals, additional stress from other family members, the stress of watching the loved one deteriorate before their eyes, the uncertainty of what would happen next and having no time for self, were obstacles to dying at home. Although, less clearly articulated, 60% of the participants in this study spoke of the positive aspects of a loved one dying at home which included a sense of being a stronger person, the ability to care for the person they love, being together and becoming closer.

Hannan and Gibson’s [24] UK interpretative phenomenological analysis of five families whose child had died of cancer explored the decisions made by parents as to place of death. The parents found the decision as to where to care for the child during the dying trajectory was based on the wish to value the time left. The parents did not make a conscious decision to be home; rather the place of care seemed obvious and natural. The care at home provided a sense of normality where family life could continue. The decision was also influenced by the child’s wishes that were associated with previous negative hospital experiences. This ability to care for the child at home was also related to the amount of health care support received, which made the parents feel more in control of the process. The uncertainty of what to expect, and how long the dying trajectory would last, created exhaustion and stress for the family, with many wanting respite towards the end. The participants also noted a difference in care from those health care professionals with specialist knowledge compared to others.

Perreault et al. [25] conducted a phenomenological study of six primary carers and four support persons. The age of the participants in this study was not mentioned but all were required to be over 18 years. The participants were asked to describe the experience of a family member caring for a dying loved one at home. The decision to care for the loved one at home was initiated at the time of diagnosis. As the illness progressed the caregivers felt a sense of helplessness and isolation, which was associated with the inability to relieve the patient’s pain and discomfort and watching the suffering associated with the progression of the disease. This was compounded by a lack of support from health care professionals and the physical and emotional limitations of the carer to provide the care required for their loved one. These factors were associated with the decision to admit the loved one into palliative care. These studies suggest that the capacity to care for an AYA at home is dependent on numerous factors which include the opportunity to engage in EOL discussions, the decisions as to when and how to stop aggressive treatment within a curative system, the amount of specialist support in the community and the ability of a carer to cope with the emotional and physical labour of caring for a loved one at home.

This literature provides evidence that the preference to die at home has numerous barriers; which include lack of honest timely communication, the emphasis on treatment in the curative system, time of referral to the palliative system, adequate support and resources in the community and the capacity of the carer to provide care during the dying trajectory.

Objectives

The purpose of the major study was to uncover, through family members telling their stories, their experience following the diagnosis, treatment, dying and death of an AYA member (aged 12-25 years). This paper as part of that study presents narrative accounts of six family member’s stories recounting the transition into palliative care focussing on the place of death.

Methodology

Narrative inquiry was chosen as the most appropriate methodology for this study. Narrative inquiry lends itself to the research aims and objectives due to its philosophical underpinnings. Narrative inquiry uses stories to describe human experience [26-28]. Frank [29] further expands this, believing stories of suffering produce a testimony of the person’s lived experience which can facilitate healing. The major study asked family members to tell the story of their son, daughter, grandson, or sibling’s cancer journey from diagnosis to death. The stories are stories of suffering and, as such, are examples of the illness narratives described by Frank [29].

Method

Full ethical approval was obtained from Southern Cross University’s Human Research Ethics Committee before the commencement of this study (Approval number ECN – 05 – 146).

Recruitment of family members

The participants in this study were a purposeful sample of family members who have experienced the death of an AYA due to cancer. The inclusion criteria included family members:

• parents, siblings and grandparents aged 12 to 65

• who had lost an AYA to cancer (aged 12-25) over 12 months previously

• who were willing to tell their story about the experience.

The family members were recruited through the media (local newspapers, local television stations and an Australian magazine). The final number of family members recruited to the study was 26. Of this 26, six of the family member’s stories tell of the experience of the transition into palliative care. Of these six all of the family member’s initially sought to care for the AYA at home Table 1 represents the family member’s relationship, AYA information and place of death.

| Family member’s relationship | AYA information | Place of death |

|---|---|---|

| Deborah. Mother of Matthew | Matthew Anthony died of alveolar soft part sarcoma in September 2003 aged 18 | Family home |

| Irene, Grandmother of Thomas | Thomas died of osteosarcoma in December 2001 aged 16 | Family home |

| Jenny, Mother of Brenton | Brenton who died of a rare sarcoma in October 2001 aged 16 | Family home |

| Fulvia, Mother of Jayde | Jadye died of rhabdomyosarcoma in December 2006 aged 17 | Hospital |

| Kerry. Mother of Alinta | Alinta died of glioblastoma in September 2001 aged 12 | Family home |

| Sue, Mother of Ben | Ben died of melanoma in May 2006, aged 18 | Hospice |

Table 1: Family Member’s Relationship to the AYA and place of death.

For the purpose of this study family preferred not to use pseudonyms and requested the AYAs and their real name be used. Additional ethical approval was obtained from Southern Cross University’s Human Research Ethics Committee for this to be possible (Approval number ECN-08-029).

Narrative Analysis

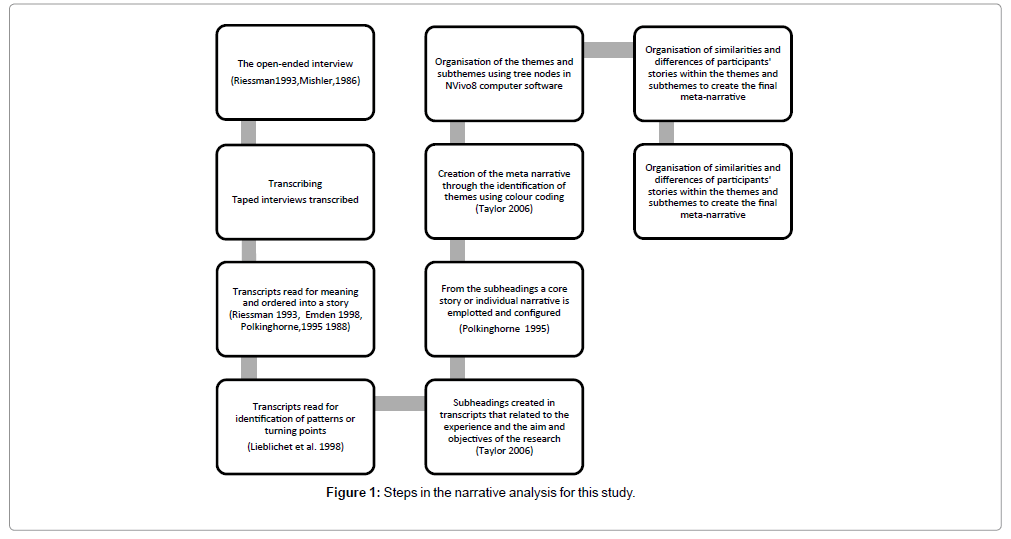

Selected methods of narrative analysis were used to analysis the stories [28,30-35]. Figure 1 links the steps of narrative analysis for this study with specific processes and relevant authors.

Results

For the family members in this study there was a point in the cancer journey when they knew the AYA was going to die. The transition into palliative care varied depending when EOL discussions were initiated. Associated with the transition was the decision of where the AYA would die. Six of the 26 family members’ spoke openly about the experience of caring for the AYA at home during this transition. The family members spoke of positive and negative experiences associated with this transition. For example, for Thomas this transition into palliative care was a positive experience, Irene spoke of how this made it easier for the family:

“They told us then there was nothing else they could do. He stayed home. So he had a lot of treatment at home … he wouldn’t stay in hospital for the last … we could pop in and see him any time we wanted to, sit beside the bed and talk to him.… on a weekend you’d go into Thomas’ bedroom and there’d be mattresses all over the floor where they’d[his friends] all stay … In the end we bought Thomas a little bar fridge to keep next to his bed, so he could keep himself some cold drinks of water without him having to struggle to get out of bed, because it was a big effort to get out of bed and reach for the crutches … we moved him from one bedroom to another, so we gave him the bedroom with the ensuite … So we tried to make things as good as we could for him … With the hospital you couldn’t all be there … they’ve got their restrictions and it wasn’t fair to other patients you know. Yes I think it was better for him to be at home. I think if any kid’s going to go through this, stay at home if you can get treatment at home rather than be in a hospital.”

In Irene’s story there is a suggestion that there was a choice as to where the care would be delivered in this transition to palliative care. This is in contrast to Jenny and Kerry who found it difficult making this transition into palliative care.

Jenny said there was no place for Brenton to go. The Children’s Hospital abandoned them and wouldn’t take him and the Hospice was for older people:

“We never had very good support through the Children’s Hospital when he was dying. I asked could he be admitted there when I couldn’t cope for a night and day. They really wiped their hands of us, “we only want children that we can cure or we can help but he is dying so no” … I said “where else can he go?” And there were no answers … They did offer the hospice around the corner here but I went around to see it and it was just full of old people and I couldn’t put my son there.”

Added to this Jenny’s felt unsupported when caring for Brenton dying at home. She found it hard and would have appreciated time out:

“I know he wanted to die at home … There was no support there for anybody really ... It was an awful time because it was just so higgledypiggledy, there was nothing in place … I’d ring the Children’s Hospital and they’d say “we’ll put you on to the pain relief people”. And you think well okay but this is not what I need. I needed to have somebody to help out with everything but there wasn’t that help … he wanted to die at home so I wanted him to be with me but I just needed a respite every so often because it was very hard work when you don’t know how long it is going to take, it’s just all really hard.”

Kerry had been told to go home as it was the best place for Alinta, however there was no help and Kerry felt overwhelmed:

“So there was no choice as far as I could see, that someone had given me a 24 hour watch, with no help … I don’t understand why that was, that I had to go home and look after her. They’re telling you that’s the best place but where was the help? They just told me to take her home. Now that’s ridiculous.”

Kerry also found it difficult to assimilate the concept of palliative care. To her palliative care was associated with going to a cemetery and looking at a grave every day:

“The doctors … they told me about the word palliative and that, you know you’ve always thought palliative was a care … So it goes with kindness because that’s what caring is, caring is nice and soft and lovely. But it’s not, it’s actually where you go when you’re dying … I said not to say that word, it makes me nearly vomit. It’s like going to a cemetery and looking in a grave every day.”

Jenny and Kerry felt they had no choice but to care for Brenton and Alinta at home with Jenny believing there was no other place and Kerry being told it was the best place for Alinta. Sue knew she couldn’t cope with Ben at home, and he returned to the hospice where he was nurtured and cared for and he was able to make his hospice room his own:

“Ben came home and he was home I think, two days, and he had a fall, his legs gave way, and I knew then he had to go back to hospital because I couldn’t lift him. He was taller than me and my husband was sinking deeper and deeper into depression, so I knew I couldn’t depend on him, so we got him back into Calvary and the people there are just angels, just fantastic. They couldn’t do enough for him, he was in his own room, they bent over backwards to get the food he wanted and they were just so caring and the room was bright, we overlooked Botany Bay … and they ( the nurses) said “look, you make this room yours,” so everyone who came in, all his friends, would bring pictures, so the whole wall was full of photos … and CanTeen (support organization for AYA’s living with cancer) made a big banner for him. They all signed that and he had that, until the day he died.”

For Deborah the transition into palliative care was made difficult when Matthew asked to go home to die. The doctor at the hospital did not want him to go home and Deborah had to insist that he be allowed to go.

“Matthew had actually said “I don’t want to keep coming to Melbourne. I’m sick of it, I just want to be at home with my family and my friends.” And they didn’t want that, they kept saying “no, no we have to keep seeing you. We have to do this” and in the end Matthew just point blank refused … and when Matthew said he wanted to die at home and not in hospital, the doctor almost laughed at him, and said “well, that’s just ridiculous” … Matt said, “well I want to go home, now,” and she said, “no you can’t go home now,” and he said “I’m going home now. Mum tells them I’m going home. I’m not going to die in hospital. If I’ve only got a week to live, I want to be at home,” and they wouldn’t let him go … and I just said “well, we’re going home. I don’t care what you say now; Matthew has expressed his wish to go home. You said he’s going to die, there’s nothing more you can do for him, we’ve got scripts for his morphine and … all his medications. We’ve got the stuff, we’re going home and he will die at home.”

Despite advocating for Mathew to die at home there were times, like Jenny and Kerry, when Deborah felt overwhelmed with the suffering of Matthew’s dying:

“The last month he was sleeping a lot more because when he was awake he was in pain and they never, ever managed his pain. It was never, ever fully under control … That’s very difficult to cope with … really hard. I mean if they have managed his pain I perhaps would’ve maybe coped a little bit better … towards the end I couldn’t deal with it because he was just screaming in agony and it was just, awful.”

This feeling of being overwhelmed with the suffering of dying is reflected in Fulvia’s story. Jadye wished to stay at home but the symptoms and the pain became so overwhelming that Fulvia believed she had no choice and Jadye had to return to hospital.

“We sat up for night after night with her screaming and all these tablets I could give her and then the next morning when she woke up she had a black eye, all her arms were bruised, she had bruises coming up everywhere … and she didn’t want to move, and she just begged me, “no leave me at home, leave me at home” and I yelled at her and made her go to the hospital and she never came home … and the first night … she was in pain and they had her drugged up … then … she sort of wasn’t herself … she was not with it … they said she was too ill, to bring home again and she was too ill to move to palliative care. [The social worker] called me again and said, “Jadye’s not coming home” and this time I knew and we [Fulvia and Jadye] talked about it for a long time … and not long after that she just laid down and she was unconscious and she sort of accepted it.”

Discussion

A good death is facilitated by people being involved in discussion about the transitions to palliative care early in the dying journey. Stillion and Papadatou [21], and Wolfe J et al. [15] recommend that palliative care be introduced concurrently with the diagnosis.

Clayton et al. [36] in their clinical practice guidelines for communicating end-of-life issues with adults, believe health care professionals are uncomfortable discussing these end of life options. The dominate communication pattern in American society is closed awareness in which everyone behaves as if the patient is not terminally ill [37]. This communication pattern has been associated with an isolated dying journey [37]. Reasons for these communication patterns are “perceived lack of training, stress, no time to attend to the patient’s emotional needs, fear of upsetting the patients and a feeling of inadequacy or hopelessness regarding the unavailability of further curative treatment”. Given these reasons for not initiating discussion on the transition to palliative care with adult patients, issues associated with AYAs and their families are even more complex and confounded.

Research demonstrates that patients believe the best place for an AYA to die is at home [16-19,21,38] a place in which Williams [39] describes as an authentic place in which the AYA and the family are psychologically rooted. Brown et al. [40] comment that a home death facilitated being there, sustained relationships, normalcy, self direction and reciprocity which are all important elements for the AYA and the AYA’s family members’ journey.

In Foreman et al. [19] survey this strong preference to die at home was particularly relevant in younger people. Grinyer and Thomas [16] believe the alienating hospital experience contributed to the young person’s wish to die at home. This is supported by Hannan and Gibson’s [24] study where they found that a child’s decision to die at home was related to negative hospital experiences. A home death is associated with the opportunity to be surrounded by family and friends [16] and to provide a sense of normality where the family life could continue [24]. This positive experience of dying at home is confirmed by Irene and Deborah’s stories. In contrast for Jenny and Kerry the decision for Brenton and Alinta to die at home was based more on necessity than choice. Both Jenny and Kerry describe a lack of support, help and coordination of care which was overwhelming and hard. It is not evident if Jenny wanted Brenton to die at home or if she would have preferred him to die in a more controlled environment. Jenny described a lack of home support for her in Brenton’s dying journey. This lack of support and feeling overwhelmed is also evident in Deborah’s story when she became overwhelmed with Matthew’s pain.

Despite the reality that most young people say they wish to die at home [16-19] and research that reveals the decision is associated with contributing to the overall quality of peoples’ lives; facilitating a sense of normality, security and personal control [41] this reality is not always possible. Williams et al. [42] have suggested that dying at home can be associated with struggle and a place of physical, emotional and organisational labour.

Morris and Thomas [41] highlight that the place of death is more complex than assumed, with the social relationship of the carer playing a significant role in the preference of place of death. This can be seen in Jenny’s account of caring for Brenton at home. Despite the exhaustion and hard work she continued caring for him at home because that was where he wanted to be. Gomes and Higginson’s [43] literature review demonstrated that the provision of intensive home care was associated with home dying. Brown et al. [40] identified the following factors associated with a home death: a willing and able caregiver; the patient is not too ill; the home environment can be adapted to meet the patient’s needs; and adequate services are provided if the patient is not too ill. Although there is a paradox in that patients with limited access to health and palliative care in rural areas were more likely to die at home [43]. This paradox suggests that perceived limited choice of place of death has an influence on dying at home, as was seen with Jenny and Kerry. In both Jenny’s and Kerry’s stories they believed there were no health services which could adequately provide the care for Brenton and Alinta, with Jenny describing the Hospice as full of old people and Kerry describing palliative care as like a cemetery.

The association of the words palliative and dying as told by Kerry is confirmed in a study by Monterosso and Kristjanson’s [20]. The study obtained feedback from semi-structured qualitative interviews from 24 parents in five tertiary paediatric oncology units across Australia. There were 10 interviews from Perth (WA), five from Melbourne (Vic), five from Brisbane (Qld) and four from Sydney (NSW). The study focused on children who had died of cancer and explored with parents their experience and understanding of palliative care. The findings affirm that the dying trajectory for parents, whose child died of cancer, is tempered with chronic uncertainty and apprehension in which parents attempt to manage the practicalities of caring for a dying child. Within this context, parents constructed palliative care negatively, with little understanding of palliative care having a wider continuous process. The study found this lack of understanding of palliative care is also characteristic of health care professionals. The authors relate that early recognition of a child’s prognosis creates stronger emphasis on lessening suffering and integration of palliative care. This is reinforced by Gomes B [44] Australian qualitative study which examined the experience of transition to palliative care from the perspective of curative and palliative care nurses and patients. The patients required time to assimilate that the focus of care had changed. Often this new understanding does not occur due to quick referrals to palliative care as a result of the pressure within the curative system. Within this context the patients were often not included in the decision making process. The suggestion of transition to palliative care was associated with fear and misunderstanding as most patients associated it with imminent death. Overlaying this was the reality that the patients’ believed they had no real choice in their transition to palliative care. Added to this reality was the fact that few patients had relevant information about what palliative care was and many only received this information when they were transferred to the Hospice. Of importance is acute care nurses lack of knowledge concerning the breadth of services available in palliative care?

The literature suggests that struggle; lack of support, lack of understanding of palliative care and the physical and emotional limitations of the carer has been associated with families lack of ability to care for the AYA at home and therefore care continuing within the hospital system [22,23,25]. This is reflected in Fulvia’s story where despite Jadye wanting to stay at home, there was a sense of being out of control and feeling powerless to manage the symptoms. This emergency hospital admission was the first time Jadye and Fulvia openly spoke about dying.

On the other hand Sue was given the choice for Ben to receive palliative care in a local hospice when the attempt to manage the dying at home was not possible. Despite Ben’s initial reluctance, the hospice provided a healing place to support Ben and Sue through the dying journey.

The therapeutic value of hospice care is confirmed by Grinyer and Thomas [16]. They found that if the dying was handled with sensitivity and respect for the AYA’s individuality, and comfort was provided for the parents, the death was less traumatic. This was further reinforced by Ronaldson and Devery [45] who described the hospice environment as a place that empowers the AYA to make choices.

Stillion and Papadatou [21] suggest other barriers associated with the ability to choose a place to die includes an unwillingness to give up on a possible cure, an inability to cope with the dying experience and isolation and helplessness in communities where hospice care for children is non-existent. This lack of hospice care for children would no doubt extend to AYAs as was noted in Jenny’s experience of not wanting to leave Brenton in the Hospice which was full of old men and believing she had been rejected by the paediatric system.

The present study suggests that the limited choices that Jenny, Kerry, Deborah and Fulvia experienced may have been a result of not enough information, and lack of co-ordination of the transition from the curative to the palliative system of care. The literature review found that the transition to palliative care is not always evident. This was particularly relevant for children dying from cancer for which aggressive treatment is maintained until the end [15,17,46-48]. This is evident in the stories in this study in particular Deborah who had to fight for Mathew Anthony to die at home as the hospital insisted that further cancer treatment was required. The stories suggest there are no guidelines within the curative system concerning when to commence the dialogue of transition to palliative care with AYAs and family members. This resulted in perceived limited choices for four of the family members who described the hardship and struggle of trying to support an AYA at home, to the extent that Fulvia had to return to the curative hospital system where Jadye died. These six stories demonstrate the importance of the EOL discussion of place of death being initiated early so the carers and the AYAs can be supported during this transitional stage through to death.

Conclusion

EOL decisions are the hardest part of the cancer journey and require time and information [49]. Effective and compassionate communication with children and their families is associated with high quality end of life care and the establishment of realistic goals [10]. The literature suggests that a home death is the preferred place of death particularly for young people [16-19]. This preferred place of death is not always possible for numerous reasons which include the emphasis on cure in the medical system, inability to manage symptoms, lack of support and the ability of the carer to manage the dying trajectory. It is not known if the AYA or the family members in this study were engaged in any formal or comprehensive discussions as to transition to palliative care.

Anghelescu et al. [50], advocate for a more holistic approach to palliative care, as a way to clearly provide appropriate care and symptom management when dying. This supports the idea that palliative care be introduced early in order for patients and family members to plan their model of care [15,18,21,38,48] which is timely and integrated [51] and structured and coordinated [38]. Research has indicated that if palliative care is introduced early, the AYA is more likely to die supported at home [38] which is their preferred place of death [16-19].

This is further reinforced by the 2010 Australian National Palliative Care Strategy [52]. Goal number two is “to enhance community and professional awareness of the scope of, and benefits of timely and appropriate access to palliative care services” [52]. The six stories in this paper provide further support for the transition into palliative care being structured and co-ordinated so the choice of where to die is coordinated and resourced to provide adequate support for the carer to facilitate a good death for the AYA.

References

- Phillips M (2009) Overview: Adolescent oncology: orphaned in the system. Cancer Forum 33.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and Australasian Association of Cancer Registries (AACR) (2004) Canberra, Australia.

- CanTeen (2005) Submission from CanTeen Australia, in Inquiry into services and treatment options for persons with cancer, S.C.A.R. Committee, Editor Australian Government Printing Services: Canberra, Australia.

- Bleyer WA (2002) Cancer in older adolescents and young adults: epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, survival, and importance of clinical trials. Med Pediatr Oncol 38: 1-10.

- Thomas DM, Seymour JF, O'Brien T, Sawyer SM, Ashley DM (2006) Adolescent and young adult cancer: a revolution in evolution? Intern Med J 36: 302-307.

- Albritton K, Bleyer WA (2003) The management of cancer in the older adolescent. Eur J Cancer 39: 2584-2599.

- Burke ME, Albritton K, Marina N (2007) Challenges in the recruitment of adolescents and young adults to cancer clinical trials. Cancer 110: 2385-2393.

- McTiernan A (2003) Issues surrounding the participation of adolescents with cancer in clinical trials in the UK. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 12: 233-239.

- O'Brien T (2006) The need for change: Why we need a new model of care for adolescents & young adults with cancer: a document for discussion in Improving the Management of Cancer Services, Melbourne.

- Hurwitz CA, Duncan J, Wolfe J (2004) Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life: "there are people who make it, and I'm hoping I'm one of them". JAMA 292: 2141-2149.

- Freyer DR (2004) Care of the dying adolescent: special considerations. Pediatrics 113: 381-388.

- George R, Craig F (2009) Palliative care for young people with cancer. Cancer Forum 33.

- George R, Hutton S (2003) Palliative care in adolescents. Eur J Cancer 39: 2662-2668.

- Beale EA, Baile WF, Aaron J (2005) Silence is not golden: communicating with children dying from cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 3629-3631.

- Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, Levin SB, Ellenbogen JM, et al. (2000) Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 342: 326-333.

- Grinyer A, Thomas C (2004) The importance of place of death in young adults with terminal cancer. Mortality 9: 114-131.

- Bell CJ, Skiles J, Pradhan K, Champion VL (2010) End-of-life experiences in adolescents dying with cancer. Support Care Cancer 18: 827-835.

- Hinds PS, Pritchard M, Harper J (2004) End-of-life research as a priority for pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21: 175-179.

- Foreman LM, Hunt RW, Luke CG, Roder DM (2006) Factors predictive of preferred place of death in the general population of South Australia. Palliat Med 20: 447-453.

- Monterosso L, Kristjanson LJ (2008) Supportive and palliative care needs of families of children who die from cancer: an Australian study. Palliat Med 22: 59-69.

- Stillion J, Papadatou D (2002) Suffer the children: An examination of psychosocial issues in children and adolescents with terminal illness. American Behavioural Scientist 46: 299-315.

- Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AE, Bannister SL (2010) Palliative care of children with brain tumors: a parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 164: 225-230.

- Hudson P (2004) Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. Int J Palliat Nurs 10: 58-65.

- Hannan J, Gibson F (2005) Advanced cancer in children: how parents decide on final place of care for their dying child. Int J Palliat Nurs 11: 284-291.

- Perreault A, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Fiset V (2004) The experience of family members caring for a dying loved one. Int J Palliat Nurs 10: 133-143.

- Bruner J (1987) Life as narrative. Social Research 54: 11-32.

- Emden C (1998) Theoretical perspectives on narrative inquiry. Collegian 5: 30-35.

- Polkinghorne D (1988) Narrative knowing and human sciences. State University of New York Press, Albany, USA.

- Frank A (1997) The wounded storyteller. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Riessman C (1993) Narrative analysis. Qualitative Research Methods Series, Sage Publications, London.

- Mishler E (1986) Research Interviewing :Context and Narrative. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, USA.

- Emden C (1998) Conducting a narrative analysis. Collegian 5: 34-39.

- Polkinghorne D (1995) Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8: 5-23.

- Lieblich A, Tulval-Mashiach R, Zilber T (1998) Narrative research : Reading analysis and interpretation. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Sage Publications London, UK.

- Taylor B (2006) Qualitative data analysis, in Research in nursing and health care: Evidence for practice. Thomson, South Melbourne, Australia.

- Clayton J, Karen M Hancock, Phyllis N Butow, Martin HN Tattersall, David C Currow (2007) Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end -of life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust186: 77-108.

- Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Ragan S (2011) The shift to early palliative care: a typology of illness journeys and the role of nursing. Clin J Oncol Nurs 15: 304-310.

- Palmer S, Thomas C (2008) A practice framework for working with 15-25 year old cancer patients treated within the adult health sector. onTrac@PeterMac Victorian Adolescent & Young Adult Cancer Service: Melbourne, Australia.

- Williams A (1998) Therapeutic landscapes in holistic medicine. Soc Sci Med 46: 1193-1203.

- Brown P, Davies B, Martens N (1990) Families in supportive care--Part II: Palliative care at home: a viable care setting. J Palliat Care 6: 21-27.

- Morris S, Thomas C (2007) Placing the dying body: Emotional and situational embodied factors in preferences for place of final care and death of cancer, in Emotional Geographies. Ashgate Publishing Group Abingdon.

- Williams PG, Holmbeck GN, Greenley RN (2002) Adolescent health psychology. J Consult Clin Psychol 70: 828-842.

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ (2006) Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ 332: 515-521.

- Barbara Gomes (2006) Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ332: 515.

- Ronaldson S, Devery K (2001) The experience of transition to palliative care services: perspectives of patients and nurses. Int J Palliat Nurs 7: 171-177.

- Klopfenstein KJ (1999) Adolescents, cancer, and hospice. Adolesc Med 10: 437-443, xi.

- Drake R, Frost J, Collins JJ (2003) The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage 26: 594-603.

- McGrath P (2001) Dying in the curative system: the haematology/oncology dilemma. Part 1. Aust J Holist Nurs 8: 22-30.

- Penson RT, Rauch PK, McAfee SL, Cashavelly BJ, Clair-Hayes K, et al. (2002) Between parent and child: negotiating cancer treatment in adolescents. Oncologist 7: 154-162.

- Anghelescu D, Oakes L , Hinds P (2004) Palliaitive Care in Pediatrics. Anaesthesiology Clinics of North America 24: 145-161.

- CanTeen and Cancer Australia (2009) National Service Delivery Framework for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer.

- Department of Health and Ageing (2010) National Palliative Care Strategy, Commonwealth of Australia Canberra.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 8150

- [From(publication date):

December-2012 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3515

- PDF downloads : 4635