Case Report Open Access

Acute Obstructive Hydrocephalus during Chemotherapy in T-Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

Andrea Piccin1*, Massimo Tripodi2, Vincenzo Cassibba1, Irene Cavattoni1, Raimondo Di Bella1, Andreas Schwarz2 and Marco Casini1

1Haematology Department and Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit, San Maurizio Regional Hospital, Bolzano, Italy

2Neurosurgery Department, San Maurizio Regional Hospital, Bolzano, Italy

- Corresponding Author:

- Andrea Piccin

Haematology Department and Bone Marrow Transplant Unit

Bolzano/Bozen, South Tyrol, Italy

Tel: +39-347-2736692

Fax: +39-0471-908703

E-mail: apiccin@gmail.com

Received date: July 11, 2014; Accepted date: September 11, 2014; Published date: September 18, 2014

Citation: Piccin A, Tripodi M, Cassibba V, Cavattoni I, Bella RD, et al. (2014) Acute Obstructive Hydrocephalus during Chemotherapy in T-Lymphoblastic Lymphoma. J Clin Diagn Res 3:110. doi:10.4172/2376-0311.1000110

Copyright: 2014 Piccin A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at JBR Journal of Clinical Diagnosis and Research

www.omicsonline.org/open-access/pattern-and-distribution-of-lymph-node-metastases-in-papillary-thyroid-cancer-2161-0681.1000204.phpKeywords

Obstructive hydrocephalus; Lethargy; Lymphoblastic lymphoma

Case Descriptions

A 32 year old male was admitted to the Accident and Emergency (AE) department suffering from acute dyspnoea, left hand finger paraesthesia, diplopia, and right abdominal paralysis for the past five days. His past medical history shows no significant information about his health history. A chest and abdominal CT-scan showed a mediastinal mass (10x12 cm) with a left pleural effusion and compression of his left bronchus and splenomegaly (13 cm). A neck CT-scan documented bilaterally an enlarged laterocervicalis and supraclavear lymphoadenopathies. The Full Blood Count (FBC) revealed Hb 11.2 g/ dL, WBC 7.20x109/L, PLT 102.00x109/L. Biochemistry and coagulative tests showed no significant gestures. Due to the large size of the mediastinal mass with associated airways compression, the patient was immediately transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The patient would be in danger due to standard chemotherapy CHOP schedule (Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone). Although confirmation of T Lymphoblastic Lymphoma was lacking, biopsy of a supraclavicular lymph node confirmed an Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia/ T-Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (ALL/LBL-T-cell) diagnosis. Cytogenetic showed a normal 46 XY male karyotype and Bone marrow biopsy was negative. A lumbar puncture showed the central nervous system’s involvement in the presence of T- lymphoid blasts in the spinal fluid.

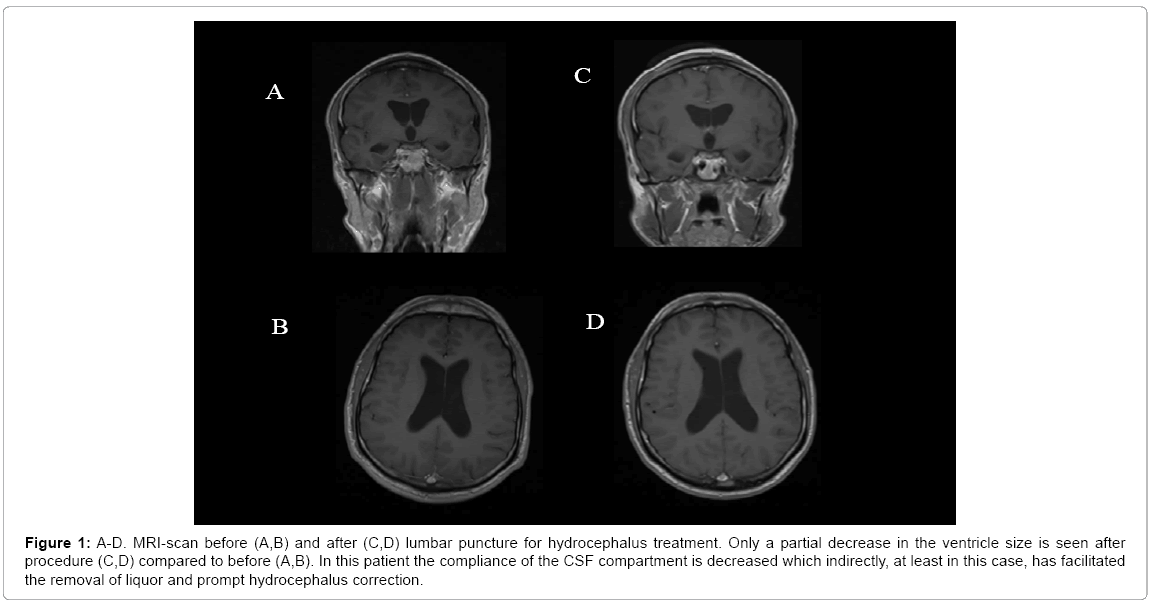

After six days of hospital admission, the patient’s condition had improved and was enrolled on Italian NILG ALL 10/07 chemotherapy protocol and was put on induction chemotherapy cycle C1 in four phases (vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 on day 1, 8,15,22; idarubicin 12 mg/ m2 on day 1-2; dexamethasone 5 mg/m2 BD on day 1-5 and 15-19; asparaginase Medac 3000 U/m2 on day 8,10,14, 17,19). Intrathechal Chemotherapy (IT) with methotrexate 12.5 mg and cytarabine 75 mg was also given twice a week (5 doses in total). After the second IT, spinal fluid (CSF- F) was found to be negative for blasts. The patient became lethargic after 27 days and no neurological deficits were observed. Biochemistry studies, rammonemia and blood gas analysis were normal. However, a reduced antithrombin of 66.6%,with an elevated PT of 1.31 and a slightly elevated PTT of 1.1 was noted. Brain CT scan reported normal; however a cerebral magnetic resonance angiography strongly indicated the presence of bilateral hydrocephalus (Figure 1). A dry tap lumbar puncture was urgently performed and 40 ml of CSF- F was removed, following which the patient immediately responded and became concious. A neurosurgical intervention was attempted with the positioning of an Ommaya reservoir. The CSF- F remained positive for blast cells and Spinal fluid microbiological testing including PCRtesting for Enterovirus, adenovirus, CMV, EBV, JCV, HHV6 , Herpes virus type-1, -2 and chickenpox virus were all negative, as was culture and staining for bacteria, fungi and mycobacterium tuberculosis and biochemical analysis.

Figure 1: A-D. MRI-scan before (A,B) and after (C,D) lumbar puncture for hydrocephalus treatment. Only a partial decrease in the ventricle size is seen after procedure (C,D) compared to before (A,B). In this patient the compliance of the CSF compartment is decreased which indirectly, at least in this case, has facilitated the removal of liquor and prompt hydrocephalus correction.

The patient was started on high dose methotrexate and cytarabin (methotrexate 3.5 g/m2 on day 1 plus cytarabine 2 g/m2 twice a day on days 2-3) as previously described Ferreri AJ et al. [1] and continued on consolidation T-ALL protocol. He recovered slowly and completed the entire chemotherapy course with good clinical benefit. The right abdominal paralysis and the upper right limb paralysis were resolved with physiotherapy.

Discussion

Cyclophosphamide and Doxorubin were reported to induce hydrocephalus [2]. In the case, the patient was administrated with the two drugs in the chemotherapy CHOP schedule and the concerns related to the two drugs should be addressed.

AOH is a life-threatening condition. Yet, if treated immediately by diversion (e.g. lumbar puncture) it can be cured. For this reason a prompt recognition is imperative. Intra-ventricular bleeding also may lead to AOH. After lumbar puncture, cerebrospinal fluid should be tested to make sure whether there is any intracranial hemorrhage.

Studies on large animals like primates, Milhorat TH and past studies shows that lethargy is the most reliable and common symptom of hydrocephalus [3]. This was also the case with the patient presented here. Other symptoms include headache and vomiting, however these are often non-specific symptoms and in children and it is interpreted as signs of gastro-enteritis, which could lead to misdiagnosis and delayed recognition of AOH.

Majority AOH cases are occurring in association with hematological malignancies and in the cases infiltrations of choroid plexus, aqueducts are common [4,5]. In many cases involvement of central nervous system (CNS) may account for up to 7%; however CNS symptoms are reported in 4% of cases only [6]. The present clinical case concerns with lymphoblastic lymphoma alone. However, according to the WHO, lymphoblastic lymphoma simply reflects leukemic bone marrow infiltration < 25% and/or the presence of a mass lesion. In the context of AOH, the difference is probably irrelevant .

Usually majority cases turn worse due to the presence of hyperleukocytosis blasts that correlates with the risk of CNS infiltration and CNS haemorrhage [7]. However, a higher incidence of AOH is not reported in the case illustrated here and the WBC was not increased without any blasts present in the peripheral blood.

CNS side effects are another major concern with the use of asparaginase and associated [8]. However, to the best of our knowledge, AOH has never been reported before in association with asparaginase. Previous studies have also showed that Cyclophosphamide [2] in mices and Doxorubin in human [9] may induce hydrocephalus. Both the drugs were used even in the present case and therefore these possibilities should also be taken into account.

Although the authors unable to explain why AOH occurred in this case, they would like to suggest the possibility of marginated leukemic cells within the CNS occluding CSF passages. In this respect, De Reuck J and other studies have already shown in a post-mortem that leukemic cells may infiltrate the arachnoidal villi and dural sinuses [10]. Switching to a high dose of chemotherapy treatment with cytarabine and methotrexate may have cleared any obstructive blasts within the aqueducts causing AOH.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of developing AOH in all the lymphoblastic lymphoma cases due to a very high WBC and CSF involvement. The symptom of lethargy should alert clinicians to immediately rule out the presence of AOH. If diagnosed, CSF diversion should be performed as a matter of urgency. In the event of death, brain post-mortem studies should be considered to clarify AOH aetiology and CNS chemotherapy efficacy.

References

- Ferreri AJ, Reni M, Foppoli M, Martelli M, Pangalis GA, et al. (2009) High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet 374: 1512-1520.

- Prakash, Singh G, Singh SM (1990) Cyclophosphamide-induced agenesis of cerebral aqueduct resulting in hydrocephalus in mice. Med Pediat Oncol 18: 261-263.

- Milhorat TH, Mary K, Hammock (1971) Interpretation of Ventricular Size and Configuration in Hydrocephalus. Arch Neurol 22: 397-407.

- Parasole R, Petruzziello F, Menna G, Mangione A, Cianciulli E (2010) Central nervous system complications during treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a single pediatric institution. Leuk Lymphoma 51: 1063-1071.

- Rahman AT, Mannan MA, Sadeque S (2008) Acute and long-term neurological complications in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Res Counc Bull 34: 90-93.

- Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D (2011) Postgraduate Haematology. Wiley-Blackwell, 20: 433-462.

- Marwaha RK, Kulkarni KP, Bansal D, Trehan A (2010) Central nervous system involvement at presentation in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: management experience and lessons. Leuk Lymphoma 5: 261-268.

- Kieslich M, Porto L, Lanfermann H, Jacobi G, Schwabe D, et al. (2003) Cerebrovascular complications of L-asparaginase in the therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J PediatrHematolOncol 25: 484-487.

- Aricó M, Nespoli L, Porta F, Caselli D, Raiteri E, et al. (1990) Severe acute encephalopathy following inadvertent intrathecal doxorubicin administration. Med PediatrOncol 18: 261-263.

- Shemie S , Jay V, Rutka J, Armstrong D (1997)Acute obstructive hydrocephalus and sudden death in children. Ann Emerg Med 29: 524-528.

Relevant Topics

- Back Pain Diagnosis

- Cardiovascular Diagnosis

- Clinical Diagnosis

- Clinical Echocardiography

- COPD Diagnosis

- Diabetes Diagnosis

- Diagnosis Methods

- Diagnosis of cancer

- Diagnosis of CNS

- Diagnosis of Diabetes

- Diagnostic Products

- Diagnostics Market Analysis

- Heart diagnosis

- Immuno Diagnosis

- Infertility Diagnosis

- Medical Diagnostic Tools

- Preimplementation Genetic Diagnosis

- Prenatal Diagnostics

- Ultrasonography

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14473

- [From(publication date):

December-2014 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9881

- PDF downloads : 4592