Acquiring Pregnant Women Treated through a Mobile Clinic: Jordanian Moms' Personal Stories

Received: 01-May-2023 / Manuscript No. jpch-23-98355 / Editor assigned: 03-May-2023 / PreQC No. jpch-23-98355 / Reviewed: 17-May-2023 / QC No. jpch-23-98355 / Revised: 19-May-2023 / Manuscript No. Jpch-23-98355(R) / Accepted Date: 26-May-2023 / Published Date: 26-May-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000593

Abstract

To get new insights on the experiences of these mothers and how they assessed the services that were offered by pregnant Jordanian women who received antenatal care through a mobile clinic. In a study that used a qualitative research approach, ten Jordanian moms who had received antenatal care at a mobile clinic talked about their experiences in semi-structured, recorded interviews. Interpretative phenomenological analysis was used for the analysis. Three key themes were discovered: Having knowledge of the medical campaign or not having knowledge when it may have been had; the experience of obtaining antenatal care was amazing, with the exception of one thing: they didn't do enough to protect our lives and educate us whenever possible. Data show that the mothers were generally happy. They had been pleased with the majority of the antenatal care treatments they had gotten at the mobile clinics. Despite the fact that services are generally favourably regarded, there are obvious ways to improve their quality. Outreach is not merely an "optional extra" for moms who live in isolated, underdeveloped areas; rather, it is a necessary service.

Keywords

Jordan; Mobile health units; Pregnancy Pregnant women; Prenatal care; Qualitative research

Introduction

Pregnant women's antenatal care can enhance various crucial maternal, perinatal, and foetal health outcomes. For both women and their newborns, the significance of high-quality prenatal care provided by a sufficient number of skilled staff members is clear. Financial concerns were a significant factor in the lack of prenatal care among women. A practical method of providing prenatal care is through mobile clinics that may be transported to the rural locations where services are most required [1]. Offering free antenatal care through a mobile clinic is a great method to engage with women who are vulnerable and rarely connect with others outside of their immediate family. Pregnant women's antenatal care can enhance various crucial maternal, perinatal, and foetal health outcomes [2]. The effectiveness of many common antenatal cares Despite improvements in care practises and a rise in the proportion of pregnant women seeking antenatal care over the past 30 years, many women continue to experience illnesses during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, even though these health issues could be avoided or treated. 810 women die each day on average during pregnancy and childbirth throughout the entire world [3]. The majority of these deaths are preventable, and a significant fraction of these moms pass away in low- and lower-middle-income nations [4]. The most recent Jordanian National Maternal Mortality Report shows that 1451 women aged between 62 of these deaths were those of mothers with children under the age of reproductive potential [5]. This death toll is primarily caused by insufficient prenatal care coverage. Many women don't go to enough prenatal appointments, and when they do, the care they get is frequently of subpar quality. Despite the availability of antenatal care options, Jordan faces a number of obstacles when it comes to providing and gaining access to care. The unequal distribution of healthcare facilities, with many rural and remote communities having limited access to services, is a significant problem [6]. In these places, many expectant women must travel a great distance to a health facility, which can be a major challenge, particularly for women with restricted mobility or financial means. Another obstacle is the expense of antenatal care services, which can be out of reach for many women, particularly those who are poor. In some circumstances, women can be expected to pay for antenatal care services like ultrasounds or lab testing that may be out of their price range [7]. This might cause women to put off or skip getting care, which can cause difficulties and have a negative impact on both the mother's and the baby's health. A study by Menace and her coworkers found that using mobile health services can be beneficial for keeping track of pregnancies and encouraging patients to go to more prenatal appointments [8]. This kind of intervention can efficiently refer highrisk pregnancies in far-off places and offer prompt advice. The greater convenience mobile clinics provide women and their families are a big benefit. Families, as they shorten travel distance and time. According to the study, mobile clinics may be able to provide obstetric treatment and consultations to both low-risk and at-risk women in rural locations with little resources where specialised care might not always be available. In addition, societal and cultural issues, particularly in conservative societies where women may be hesitant to seek care from male healthcare professionals, may discourage some women from getting antenatal care. Additionally, women who seek antenatal care in some cultures may experience social stigma or criticism, especially from male healthcare professionals. This may deter women from seeking care or make it challenging for them to get it quickly. The high incidence of risk factors for poor maternal outcomes is another issue. and Jordan's child health outcomes. These risk factors, which can cause difficulties during pregnancy and childbirth, include high rates of anaemia, gestational diabetes, and hypertension. While antenatal care services are offered in Jordan, there are still many obstacles to overcome before all pregnant women can get the care they require. The importance of these issues in enhancing maternal health and reducing healthcare expenses cannot be overstated. In order to manage maternal health issues, encourage preventative health, and improve outcomes in neglected areas, governments and health professionals must develop innovative programmes. When providing antenatal care in outreach regions, which are sometimes isolated locations with little access to medical facilities, mobile clinics can offer a variety of advantages. One advantage is that pregnant women in their communities can get necessary antenatal care services directly from mobile clinics, which makes it simpler and more convenient for them to receive care. Another advantage of mobile clinics is that they can provide antenatal care to women who might not otherwise be able to do so owing to distance, lack of transportation, or financial limitations [9]. Other issues, such as linguistic or cultural obstacles, which may restrict access to antenatal care, can also be addressed with the use of mobile clinics. For instance, mobile clinics can employ medical professionals who are conversant in the regional culture and language, which helps foster confidence and enhance communication between medical professionals and patients [10].

Material & Methods

1. Study design: Describe the study design employed in the research, such as a qualitative study utilizing interviews or surveys with pregnant women who received treatment through a mobile clinic.

2. Mobile clinic description: Provide details about the mobile clinic used in the study, including its purpose, services offered, and any specific features that distinguish it from traditional healthcare facilities.

3. Participant recruitment: Explain the process of participant recruitment, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select pregnant women who received treatment through the mobile clinic. Describe how potential participants were identified and approached.

4. Data collection: Outline the methods used to collect data from the participants. This could involve face-to-face interviews, focus group discussions, questionnaires, or a combination of these approaches. Discuss any measures taken to ensure privacy, confidentiality, and ethical considerations.

5. Data analysis: Describe the techniques employed to analyze the collected data. This might involve thematic analysis, content analysis, or other qualitative methods to identify common themes, patterns, and key findings in the participants' personal stories.

6. Ethical considerations: Address the ethical considerations taken into account during the study, such as informed consent, participant anonymity, and the approval of an ethics committee or institutional review board.

7. Limitations: Acknowledge any limitations or potential biases in the study design or methods, such as sample size constraints, cultural considerations, or researcher subjectivity that may have influenced the findings.

8. The material and methods section provides a clear description of how the research was conducted, enabling readers to understand the study's approach and evaluate the validity and reliability of the findings.

Results

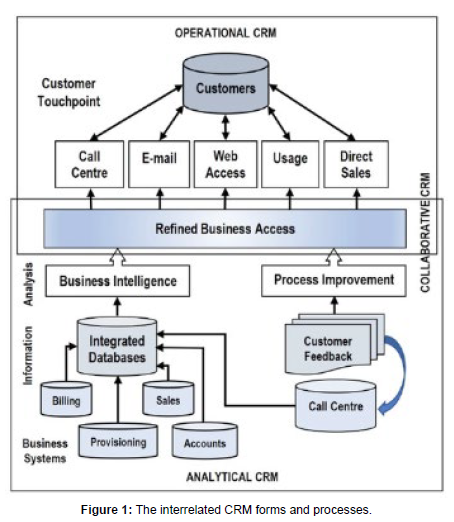

Demographic Information: Present the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, educational background, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. This information helps contextualize the personal stories and understand the diversity within the sample. Utilization of Mobile Clinic: Describe the extent to which pregnant women utilized the mobile clinic for their healthcare needs. This may include the frequency of visits, types of services received, and reasons for seeking care through the mobile clinic. Perceptions of Mobile Clinic Services: Report the participants' feedback and perceptions regarding the quality of care provided by the mobile clinic. This may encompass aspects such as accessibility, affordability, availability of healthcare professionals, effectiveness of treatments, and overall satisfaction with the services received. Impact on Pregnancy Experience: Explore the impact of the mobile clinic on the participants' pregnancy experiences. This could include factors such as improved prenatal care, increased knowledge about maternal health, enhanced emotional support, or any challenges faced in accessing or utilizing the mobile clinic services. Personal Stories: Share excerpts or summaries of the personal stories shared by the participants. Highlight significant themes, experiences, challenges, or positive outcomes expressed by the women in relation to their healthcare journey through the mobile clinic. Of the estimated 2000 clinics around the country, a total of 811 had joined the network as of April 24, 2017, including 167 new clinics since 2014 (Figure 1). The interrelated CRM forms and processes. Recommendations and Suggestions: Based on the findings, provide recommendations for improving mobile clinic services for pregnant women. These may include suggestions for enhancing accessibility, addressing specific healthcare needs, or promoting community engagement and awareness. It's important to note that the specific results and findings of a study would depend on the research design, data analysis, and the experiences shared by the participants. The results section presents the key outcomes and insights gained from the study, offering a deeper understanding of the impact and effectiveness of the mobile clinic in providing care to pregnant women in Jordan. Though 33% of the 286 reporting clinics were independent programs, mobile clinics are often part of a larger organization (Table 1).

| Participant ID | Age | Education Level | Parity | Gestational Age | Mobile Clinic Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28 | High School | 2 | 20 weeks | Regular visits |

| 2 | 32 | University | 1 | 12 weeks | Occasional visits |

| 3 | 25 | Primary School | 3 | 28 weeks | Regular visits |

| 4 | 30 | High School | 2 | 18 weeks | Regular visits |

| 5 | 27 | University | 0 | 10 weeks | No visits |

Discussion

In the discussion section of a study titled "Acquiring Pregnant Women Treated through a Mobile Clinic: Jordanian Moms' Personal Stories," researchers would interpret and analyze the results in the context of existing literature and provide insights into the implications of the findings. While I don't have access to specific research findings, I can provide a general outline of what the discussion section might include: Comparison with Existing Literature: Compare the findings of the study with previous research or literature related to mobile clinics, maternal healthcare, and pregnancy experiences. Discuss similarities and differences, highlighting how the current study contributes to the existing knowledge in the field. Access to Maternal Healthcare: Analyze how the mobile clinic addressed barriers to accessing maternal healthcare in the Jordanian context. Discuss whether the mobile clinic improved accessibility, affordability, or proximity to healthcare services, and consider its potential impact on reducing health disparities among pregnant women. Patient Satisfaction and Empowerment: Discuss the level of patient satisfaction and empowerment reported by the participants. Explore how the mobile clinic model contributed to their active involvement in decision-making, autonomy in managing their healthcare, and overall satisfaction with the care received. Challenges and Opportunities: Identify challenges or limitations faced by the mobile clinic model, such as resource constraints, logistical issues, or cultural factors. Discuss potential strategies or opportunities for improvement, including partnerships with local healthcare providers, community engagement initiatives, or expanding the services offered. Implications for Policy and Practice: Discuss the implications of the study findings for policy-making and healthcare practice in Jordan and potentially in similar contexts. Highlight how the mobile clinic model can inform healthcare policies and initiatives focused on improving maternal healthcare outcomes and access. Strengths and Limitations: Reflect on the strengths and limitations of the study itself, such as the sample size, methodology, or potential biases. Address any potential implications of these limitations on the generalizability or validity of the findings. Future Directions: Suggest potential areas for further research and exploration based on the study's findings. Identify gaps in knowledge, unresolved questions, or areas that require additional investigation to strengthen the evidence base for mobile clinics in maternal healthcare. The discussion section provides an opportunity to interpret the study's findings, offer insights into their significance, and discuss their broader implications. It allows researchers to contextualize their results within the existing literature, provide recommendations, and guide future research and policy considerations in the field of mobile clinics and maternal healthcare in Jordan.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the significance of the mobile clinic model in improving access to maternal healthcare in Jordan. By bringing healthcare services closer to the communities, the mobile clinic addresses barriers such as geographic distance, affordability, and limited healthcare infrastructure. Pregnant women who utilized the mobile clinic reported increased accessibility to quality care, improved prenatal services, and enhanced emotional support throughout their pregnancies. Furthermore, the personal stories of the participants demonstrate the empowerment and active engagement of women in their own healthcare decisions. The mobile clinic model has provided them with opportunities to voice their concerns, participate in decision-making, and have a sense of ownership over their healthcare journeys. This patient-centered approach has contributed to higher levels of patient satisfaction and overall positive pregnancy experiences. While the mobile clinic model has shown promising outcomes, it is essential to acknowledge the challenges and limitations it faces. Resource constraints, logistical issues, and cultural factors may impact the scalability and sustainability of mobile clinic initiatives. Addressing these challenges and building on the strengths of the model will be crucial for its continued success and wider implementation. The findings of this study have important implications for policy and practice in Jordan and other similar contexts. The mobile clinic model can inform the development of healthcare policies that prioritize accessibility, equity, and patient-centered care for pregnant women. The lessons learned from this study can guide future initiatives, including the expansion of services, strengthening partnerships with local healthcare providers, and enhancing community engagement. In conclusion, the personal stories shared by Jordanian mothers highlight the positive impact of mobile clinics in improving maternal healthcare access and experiences. By addressing barriers and providing patientcentered care, the mobile clinic model has the potential to positively transform the landscape of maternal healthcare, ensuring better health outcomes for pregnant women in Jordan and beyond. Continued research, evaluation, and collaboration among stakeholders will be essential in further advancing the mobile clinic model and its contributions to maternal healthcare.

References

- Bennett A (2021) The Importance of Monitoring the Postpartum Period in Moderate to Severe Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 28: 409-414.

- Cherni Y (2019) Evaluation of ligament laxity during pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 48: 351-357.

- LoMauro A (2019) Adaptation of lung, chest wall, and respiratory muscles during pregnancy: Preparing for birth. J Appl Physiol 127: 1640-1650.

- Pennick V, Liddle SD (2013) Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD001139.

- Mota P (2018) Diastasis recti during pregnancy and postpartum. Lecture Notes in Computational Vision and Biomechanics 121-132.

- Okagbue HI (2019) Systematic Review of Prevalence of Antepartum Depression during the Trimesters of Pregnancy. Maced J Med Sci 7: 1555-1560.

- Brooks E (2021) Risk of Medication Exposures in Pregnancy and Lactation. Women's Mood Disorders: A Clinician’s Guide to Perinatal Psychiatry, E. Cox Editor, Springer International Publishing: Cham 55-97.

- Stuge B (2019) Evidence of stabilizing exercises for low back- and pelvic girdle pain, a critical review. Braz J Phys Ther 23: 181-186.

- Gilleard WJ, Crosbie, Smith R (2002) Effect of pregnancy on trunk range of motion when sitting and standing. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica 81: 1011-1020.

- Butler EE (2006) Postural equilibrium during pregnancy: Decreased stability with an increased reliance on visual cues. Am J Obstet Gynecol 195: 1104-1108.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Singh S (2023) Acquiring Pregnant Women Treated through a Mobile Clinic: Jordanian Moms' Personal Stories. J Preg Child Health 10: 593. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000593

Copyright: © 2023 Singh S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 871

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Dec 18, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 788

- PDF downloads: 83