Research Article Open Access

Absence of Anaplasmataceae DNA in Wild Birds and Bats from a Flooded Area in the Brazilian Northern Pantanal

Luana Gabriela Ferreira dos Santos1, Tatiana Ometto2, Jansen de Araújo2, Luciano Matsumya Thomazelli2, Leticia Pinto Borges1, Dirceu Guilherme Ramos3, Edison Luis Durigon2, Joao Batista Pinho4 and Daniel Moura de Aguiar1*1Laboratorio de Virologia e Rickettsioses, Hospital Veterinario, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brazil

2Laboratorio de Virologia Clinica e Molecular NB3+, Departamento de Microbiologia, Instituto de Ciencias Biomedicas II, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil

3Laboratorio de Parasitologia e Doencas Parasitarias, Hospital Veterinario, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brazil

4Laboratório de Ecologia de Aves, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brazil

- *Corresponding Author:

- Daniel Moura de Aguiar

Laboratorio de Virologia e Rickettsioses, Hospital Veterinario

Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso. Av. Fernando Correa

2367, Boa Esperanca, Cuiaba, Brazil

Tel: +55 65 36158627

E-mail: danmoura@ufmt.br

Received Date: August 06, 2013; Accepted Date: September 02, 2013; Published Date: September 09, 2013

Citation: dos Santos LGF, Ometto T, de Araújo J, Thomazelli LM, Borges LP (2013) Absence of Anaplasmataceae DNA in Wild Birds and Bats from a Flooded Area in the Brazilian Northern Pantanal. Air Water Borne Diseases 2:113. doi:10.4172/2167-7719.1000113

Copyright: © 2013 dos Santos LGF, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Air & Water Borne Diseases

Abstract

Birds and bats can be considered potential transmitters of some tick-borne diseases, since eventually they carry infected ticks in areas where transit. Pantanal ecosystem is the largest tropical wetland area of the world with more than 582 recorded avian species, contributing to the maintenance of different tick species. The aim of this study was to examine altogether 152 blood samples of several bird and bat species collected in a large flooded area of Pantanal for the presence of members from genera Ehrlichia, Anaplasma and Neorickettsia. None PCR product was obtained, what suggest that wild, domestic birds and bats from Pantanal region are unlikely to play a significant role in the maintenance of tick-borne agents and DNA survey from this species in birds may not be a reliable indicator of exposure.

Keywords

Tick-borne disease; Anaplasmataceae; Fowl; Poconé; Brazil

Introduction

Birds and bats can act as reservoirs of several pathogens including those transmitted by ticks and flies. Some infections can be transmitted by trematode-vectors, which use freshwater snails and aquatic insects as intermediate hosts and insectivorous birds and bats as definitive hosts. They also can be considered as potential transmitters of some tickborne diseases, mainly due to its migratory character, since eventually they carry the infected ticks in areas where transit. Agents that stand out are the bacteria from Anaplasmataceaes family that already have been widely associated with disease in humans and animals, with cycle involving invertebrate vectors. Pathogens such as Ehrlichia, Anaplasma and Neorickettsia are being increasingly recognized around the world in order to elucidate the importance of its infections and ability to cause illness in animals and/or human beings [1-4].

Anaplasmataceae agents comprise obligate intracellular bacteria that can cause disease in humans and animals, whose cycle in the environment involves complex interactions between invertebrate vectors and vertebrate hosts [5]. There is ecological evidence that passerine birds, at least in principle, could be competent reservoirs for A. phagocytophilum as many avian species host larval and nymphal I. scapularis ticks [6,7]. Exposure of passerines to A. phagocytophilum-infected nymphs has been demonstrated [8], including infected larvae found attached to an American robin (Turdus migratorius) and a veery (Catharus fuscescens) [9]. However, direct evidence demonstrating birds as competent reservoirs of members from the family Anaplasmataceae are still scarce.

For instance in Brazil, Machado et al. [1] was the only one that reported molecular detection of A. phagocytophilum in carnivorous and migratory birds. Additionally they also reported for the first time DNA of E. chaffeensis and an Ehrlichia species, phylogenetically related to E. canis in birds sampled in Mato Grosso and Sao Paulo state.

Neorickettsia risticii (formerly Ehrlichia risticii) belongs to the Anaplasmataceae family and is the causative agent of Potomac Horse Fever (also known as Equine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis- EME), a severe febrile disease affecting horses, typically found in endemic countries during the warmest months. In the environment, N. risticii infects trematodes from the genus Acanthatrium and Lecithodendrium. The lifecycles of these trematodes are not very clear, both are known to involve several stages that range from free-living cercaria to forms that infect invertebrates such as the miracidia and sporocysts (that infect freshwater snails) and the metacercaria (that infect aquatic insects) [10].

In enzootic areas of USA, a common pleurocerid snail, Juga yrekaensis is suspected to be involved in the life cycle of N. risticii [11]. Additionally, DNA from N. risticii has been detected in virgulate cercariae in lymnaeid snails (Stagnicola spp.) in virgulate xiphidiocercariae isolated from pleurocerid snails Elimia livescens and Elimia virginica, indicating that other species of freshwater snails may also harbor infected trematodes [12,13]. Adult forms of these trematodes develop in the intestine of insectivorous vertebrates such as bats and birds, therefore it has been suggested that certain species of bats and birds (swallows) may act as wild reservoirs of N. risticii [14,15]. Recently, molecular detection of N. risticii in bats of the species Tadarida brasiliensis was reported in Argentina [16].

In Brazil, spontaneous outbreaks of equine monocytic Ehrlichiosis (EME) were described in south region [17-19]. In Rio Grande do Sul state, snails from the genus Heleobia, harboring Parapleurolophocercous cercarie, have been identified as carriers of N. risticii [18]. Three species are extremely abundant both in permanent streams and small rivers and on temporarily flooded areas of the Pantanal, namely Marisa planogyra, Pomacea linearis and Pomacea scalaris [20]. Apple snails Pomacea lineata are widespread in the tropical regions of Brazil as well as in the Pantanal wetland of Mato Grosso in the western part of the country. This species serve as food for many animals, mainly birds, fishes and caimans [21].

The Pantanal ecosystem is the largest tropical wetland area of the world, situated among two Brazilian states (Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul) and in portions of Bolivia and Paraguay. The Pantanal is characterized by an immense diversity, where more than 80 species of mammals [22] and 582 avian species, contributing to the maintenance of different tick species have already been recorded [23-25]. Furthermore the aquatic environment can favor the establishment of different species of trematodes, metacercarias and snails which jointly with birds and bats support the occurrence of N. risticii in the area. Nevertheless, the role of birds and bats in the epidemiology of tick- and water-borne diseases has been poorly studied, and the connection between birds, dispersal of infected ticks, rickettsial agents and zoonosis outbreaks need to be clarified. The aim of this study was to evaluate blood samples of several birds and bats species collected in the northern Brazilian Pantanal for the presence of members from genera Ehrlichia, Anaplasma and Neorickettsia.

Materials and Methods

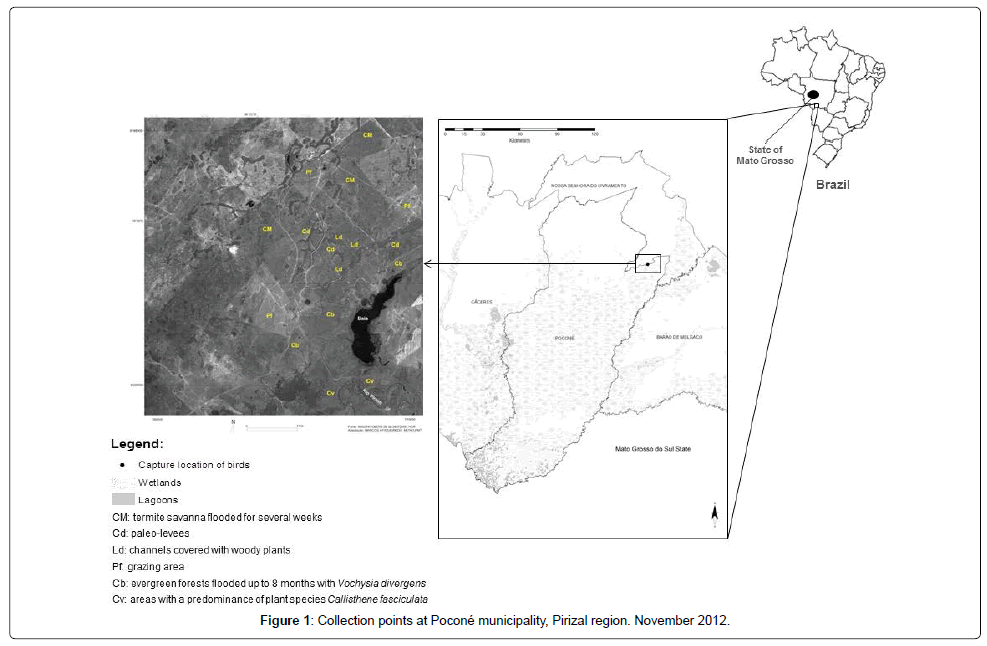

Samples of whole blood stored in cryopreserved bank were evaluated. Blood samples were collected in the Pocone municipality at the locality called Pirizal (16°15’12’’S 56°22’12’’W; Figure 1) during November 2012, totaling 152 samples from domestic and wild birds and bats. Regarding tick infestation, no information was obtained from the samples studied. Blood samples were subjected to DNA extraction protocol [26] using guanidine thiocyanate and DNA samples were tested individually for detection of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp. and N. risticii, according to the protocols described in Table 1.

| Pathogen | Primer* | Sequence(5’ - 3’) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ehrlichia spp. | dsb 330 (1s) dsb 720 (1sand2nd) dsb 380 (2nd) |

GATGATGTTTGAAGATATSAAACAAAT CTATTTTACTTCTTAAAGTTGATAWATC ATTTTTAGRGATTTTCCAATACTTGG |

[38] |

| Anaplasma spp | gE3a (1s) gE10R (1s) gE2 (2nd) gE9F (2nd) |

CACATGCAAGTCGAACGGATTATTC TTCCGTTAAGAAGGATCTAATCTCC GGCAGTATTAAAAGCAGCTCCAGG AACGGATTATTCTTTATAGCTTGCT |

[39] |

| Neorickettsia risticii | ER3(1s) ER2(1s) ER3a (2nd) ER2a (2nd) |

ATTTGAGAGTTTGATCCTGG GTTTTAAATGCAGTTCTTGG CTAGCGGTAGGCTTAAC CACACCTAACTTACGGG |

[40] |

* 1s = first reaction (PCR), 2nd = second reaction (nPCR)

Table 1: Primers and protocols used in the study of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp. and Neorickettsia risticii in birds and bats from the northern Brazilian pantanal.

All products obtained in the reactions were subjected to gel electrophoresis in horizontal 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 mL/ml - Invitrogen®) and 1X TBE running buffer pH 8.0 (44.58 M Tris-base, 0.44 M boric acid, 12.49 mM EDTA) to 110v/50mA with subsequent visualization under ultraviolet light (UV) in a darkroom. In order to prevent PCR contamination, DNA extraction, reaction set-up, PCR amplification and electrophoresis were performed in separate rooms. DNA of Sao Paulo strain of E. canis, A. platys from dog blood diagnosed with anaplasmosis and strain Illinois of N. risticii gently provide by Dr. S. Dumler was used as positive control in all reaction. Samples were collected under license granted by the Authorization System and Biodiversity Information - SISBIO number 33602-1.

Results and Discussion

One hundred and sixteen species of wild birds were captured and characterized [27-30]. Thirteen domestic fowl (Gallus gallus) were also evaluated, although there are no previous reports of Anaplasmatacea pathogens in this avian species. In addition, twenty-three blood samples from nectar-feeding bat Glossophaga soricina (Phyllostomidae) [31] were collected. All wild birds collected and their main features are shown in the Table 2.

| Family | Nomenclature | Common name | Feeding | Character* | N* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbidae | Columbina picui Patagioenas cayennensis | Rolinha-picui Pomba-galega | Granivorous and Frugivorous Granivorous and Frugivorous |

Residents Residents | 2 |

| Corvidae | Cyanocorax cyanomelas | Gralha-do-Pantanal | Omnivorous | Residents | 1 |

| Cuculidae | Coccyzus euleri | Papa-lagarta-de-euler | Insectivorous | INTRA | 1 |

| Dendrocolaptidae | Dendroplex picus | Arapaçu-de-bico-branco | Insectivorous | Residents | 4 |

| Emberizidae | Volatinia jacarina Sporophila caerulescens Sporophila angolensis |

Tiziu (Esporofilo) Coleirinho Curió |

Granivorous Granivorous Granivorous |

INTRA INTRA INTRA |

3 |

| Furnariidae | Furnarius rufus Certhiaxis cinnamomeus Cranioleuca vulpine Synallaxis albilora |

João-de-barro Curutié Arredio-do-rio João-do-pantanal |

Insectivorous Insectivorous Insectivorous Omnivorous |

Residents √?¬† Residents Residents √?¬† Residents |

14 |

| Galbulidae | Galbula ruficauda | Ariramba-de-cauda-ruiva | Insectivorous | Residents | 1 |

| Icteridae | Cacicus cela Agelaioides badius |

Xexéu (guaxo amarelo) Asa-de-telha |

Omnivorous Frugivorous |

Residents Residents |

4 |

| Parulidae | Basileuterus flaveolus | Canário-do-mato | Insectivorous | Residents | 2 |

| Phasianidae | Gallus gallus | Galinha | Omnivorous | Residents | 13 |

| Picidae | Veniliornis passerinus Picumnus albosquamatus |

Picapauzinho-anão Pica-pau-anão-escamado |

Insectivorous Insectivorous |

Residents Residents |

5 |

| Pipridae | Antilophia galeata Neopelma pallescens |

Soldadinho Fruxu-do-cerradão |

Frugivorous Insectivorous |

Residents Residents |

8 |

| Polioptilidae | Polioptila dumicola | Balança-rabo-de-máscara | Insectivorous | Residents | 2 |

| Rhynchocyclidae | Todirostrum cinereum Herpsilochmus longirostris Poecilotriccus latirostris Hemitriccus margaritaceiventer |

Ferreirinho-relógio Chorozinho-de-bico-comprido Ferreirinho-de-cara-parda Olho-de-ouro |

Insectivorous Insectivorous Insectivorous Insectivorous |

Residents Residents Residents Residents |

12 |

| Thamnophilidae | Cercomacra melanaria Thamnophilus pelzelni |

Chororó-do-pantanal Choca-do-planalto |

Insectivorous Insectivorous |

Residents Residents |

7 |

| Thraupidae | Ramphocelus carbo Saltator similis Paroaria capitata Tachyphonus rufus Lanio penicillatus |

Pipira-vermelha Trinca-ferro Galo-da-campina-pantaneiro Pipira-preta Pipira-da-taoca |

Omnivorous Omnivorous Omnivorous Omnivorous Omnivorous |

Residents Residents Residents Residents Residents |

21 |

| Tityridae | Tityra inquisitor | Anhambé-de-boina | Omnivorous | Residents | 1 |

| Turdidae | Turdus rufiventris | Sabiá-laranjeira | Omnivorous | Residents | 1 |

| Tyrannidae | Myiarchus tyrannulus Elaenia chilensis Cnemotriccus fuscatus Myiarchus ferox Myiarchus swainsonii Myiopagis viridicata |

Maria-cavaleira-de-rabo-enferrujado Guaracava-de-crista-branca Guaracavuçu Maria-cavaleira Irré Guaracava-de-crista-alaranjada |

Omnivorous

Omnivorous Insectivorous Omnivorous Omnivorous Omnivorous |

INTRA

INTRA INTRA INTRA INTRA INTRA |

27 |

| Phyllostomidae | Glossophaga soricina | Morcego-beija-flor | Nectar-feeding | - | 23 |

* INTRA: Intracontinental migrant southern and northern South America.

*N: collected number

Table 2: Birds and bats collected in Pantanal region and main features.

Wild birds may play a role as carriers of Anaplasmataceae agents in Brazil as previously described by Machado et al. [1], therefore the choice of collection points were intended to catch birds in different subtypes of the Pantanal and to cover the major habitat types in each region (data not shown), according to the applied model RAPELD PPBIO [32]. Despite the wide range of collections, in our study no PCR product was obtained from either Anaplasma spp., Ehrlichia spp. or N. risticii.

Machado et al. [1] reported the presence of DNA of A. phagocytophilum, E. chaffeensis and an Ehrlichia species closely related to E. canis in carnivorous avian blood samples, but ectoparasites were not found parasitizing birds. Furthermore, the positive birds had carnivorous habits while no other one avian family were detected with Anaplasmataceae DNA. These finding infer that the absence of detection of pathogens in our study may be related to the fact that the birds were not able to develop bacteremia or did not have carnivorous habits, probably because feeding habits of birds may imply in differences in the occurrence of infection, once the eating habits can influence the willingness of birds to certain pathogens and these habits can vary widely between birds depending on the region studied [33]. Johnston et al. [4] in an experimental study showed that the American robin (Turdus migratorius (L.)) are able to infect I. scapularis larval feeding ticks without developing bacteremia, specific antibodies or significant illness because of exposure.

Due to the fact of the samples were derived from cryopreserved blood banks, information on tick infestation could not be obtained. Studies regarding Anaplasmataceae agents infection in ticks collected from wild birds has been performed for a better understanding of the dynamics between birds and ticks and there is a concordance between the authors that the involvement of birds in the ecology and epidemiology of tick-borne diseases still unclear [34-37].

Bjoersdorff et al. [2] found a large number of migratory birds infested with Ehrlichia positive I. ricinus ticks and Ehrlichia 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences found in these ticks were identical to the HGE Ehrlichia found in humans in Sweden and Slovenia, what suggest that birds may play an important role in the dispersal of I. ricinus infected and may contribute to the distribution of granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Besides, none I. ricinus larvae infected were observed by Bjoersdorff et al. [2] which may suggest that migratory birds are incompetent reservoirs of Ehrlichia spp [38] and act just as long-distance carriers of infected ticks. Transovarial transmission of Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species [39] has not been demonstrated, so reservoir hosts are necessary to maintain the life cycle in the environment [5].

In the environment, N. risticii infects trematodes and adult forms may develop in the intestine of insectivorous vertebrates. Cicuttin et al. [16] related the first detection of N. risticii in internal organs of insectivorous bats (Brazilian free-tailed bat Tadarida brasiliensis) from Argentina and associated this species as reservoirs of these pathogens. G. soricina bats captured in the Pantanal region are known for nectar-feeding habits, thus this feature impairs contact with infected trematodes and this species may not act as wild reservoirs of N. risticii.

In view of the potential presence of N. risticii [40] especially in the Pantanal area, further studies involving bats species in this region should elucidate the potential involvement in the transmission of this agent in Brazil. Nevertheless a more detailed study should be analyzed as the presence of species of trematodes and snail in the Pantanal, since snails of the genera reported in the Pantanal have been found in properties with the occurrence of EME in other regions of Brazil [18,19].

Our results suggest that wild and domestic birds and bats from Pantanal region are unlikely to play a significant role in the maintenance of Anaplasmataceae agents and DNA survey from this species may not be a reliable indicator of exposure. More studies investigating the ecological factors and ticks burden in avian or bats hosts are needed to improve the understanding on the dynamics of Anaplasmataceae diseases in the relative area. Future efforts should include ticks identification in birds and bats from the Pantanal and experimental evaluations to understand the mechanisms that drives bird exposure risk and susceptibility to ticks and tick-borne diseases.

Acknowledgement

We thank to Rafael W. Wolf for technical support. This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnologico (CNPq research grant and scholarship to DMA), Ministerio da Educacao (MEC scholarships to LGFS), Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES graduating scholarships to LPB and DGR), Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP graduating scholarships to TO and JA).

References

- Machado RZ, André MR, Werther K de Sousa E, Gavioli FA, et al. (2012) Migratory and carnivorous birds in Brazil: reservoirs for Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 12: 705-708.

- Bjöersdorff A, Bergström S, Massung RF, Haemig PD, Olsen B (2001) Ehrlichia-infected ticks on migrating birds. Emerg Infect Dis 7: 877-879.

- Pusterla N, Hagerty D, Mapes S, Vangeem J, Groves LT, et al. (2013) Detection of Neorickettsia risticii from various freshwater snail species collected from a district irrigation canal in Nevada County, California. Vet J 197: 489-491.

- Johnston E, Tsao JI, Muñoz JD, Owen J (2013) Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in American robins and gray catbirds: an assessment of reservoir competence and disease in captive wildlife. J Med Entomol 50: 163-170.

- Dumler JS, Barbet AF, Bekker CP, Dasch GA, Palmer GH, et al. (2001) Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales: unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma, Cowdria with Ehrlichia and Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia, descriptions of six new species combinations and designation of Ehrlichia equi and 'HGE agent' as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51: 2145-2165.

- Stafford KC 3rd, Bladen VC, Magnarelli LA (1995) Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) infesting wild birds (Aves) and white-footed mice in Lyme, CT. J Med Entomol 32: 453-466.

- Hamer SA, Tsao JI, Walker ED, Hickling GJ (2010) Invasion of the lyme disease vector Ixodes scapularis: implications for Borrelia burgdorferi endemicity. Ecohealth 7: 47-63.

- Hildebrandt A, Franke J, Meier F, Sachse S, Dorn W, et al. (2010) The potential role of migratory birds in transmission cycles of Babesia spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Rickettsia spp. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 1: 105-107.

- Daniels TJ, Battaly GR, Liveris D, Falco RC, Schwartz I (2002) Avian reservoirs of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis? Emerg Infect Dis 8: 1524-1525.

- Wilson J, Pusterla N, Bengfort J, Arney L (2006) Incrimination of mayflies as a vector of Potomac Horse Fever in an outbreak in Minnesota. Medicine II AAEP Proceedings 52: 324-328.

- Barlough JE, Reubel GH, Madigan JE, Vredevoe LK, Miller PE, et al. (1998) Detection of Ehrlichia risticii, the agent of Potomac horse fever, in freshwater stream snails (Pleuroceridae: Juga spp.) from northern California. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 2888-2893.

- Reubel GH, Barlough JE, Madigan JE (1998) Production and characterization of Ehrlichia risticii, the agent of Potomac horse fever, from snails (Pleuroceridae: Juga spp.) in aquarium culture and genetic comparison to equine strains. J Clin Microbiol 36: 1501-1511.

- Kanter M, Mott J, Ohashi N, Fried B, Reed S, et al. (2000) Analysis of 16S rRNA and 51-kilodalton antigen gene and transmission in mice of Ehrlichia risticii in virgulate trematodes from Elimia livescens snails in Ohio. J Clin Microbiol 38: 3349-3358.

- Pusterla N, Johnson EM, Chae JS, Madigan JE (2003) Digenetic trematodes, Acanthatrium sp. and Lecithodendrium sp., as vectors of Neorickettsia risticii, the agent of Potomac horse fever. J Helminthol 77: 335-339.

- Gibson KE, Rikihisa Y, Zhang C, Martin C (2005) Neorickettsia risticii is vertically transmitted in the trematode Acanthatrium oregonense and horizontally transmitted to bats. Environ Microbiol 7: 203-212.

- Cicuttin G, Boeri E, Beltrán F, Gury D, Federico E (2013) Molecular detection of Neorickettsia risticii in Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Pesq Vet Bras 33: 648-650.

- Dutra F, Schuch LF, Delucchi E, Curcio BR, Coimbra H, et al. (2001) Equine monocytic Ehrlichiosis (Potomac horse fever) in horses in Uruguay and southern Brazil. J Vet Diagn Invest 13: 433-437.

- Coimbra H, Schuch L, Veitenheimer-Mendes L, Meireles M (2005) Neorickettsia (Ehrlichia) risticii no sul do brasil: Heleobia spp. (Mollusca: Hydrobilidae) e Parapleurolophocecous cercariae (trematoda: digenea) como possíveis vetores. Arq Inst Biol São Paulo 72: 325-329.

- Coimbra H, Fernandes C, Soares M, Meireles M, Radamés. R, et al. (2006) Equine monocytic Ehrlichiosis in Rio Grande do Sul: clinical, pathological and epidemiological aspects. Pesq Vet Bras 26: 97-101.

- Heckman CW (1998) The Pantanal of Poconé: Biota and Ecology of the Northern Section of the World’s Largest Pristine Wetland. Monographiae Biologicae 77, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- Fellerhoff C (2002) Feeding and growth of apple snail Pomacea lineata in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil--a stable isotope approach. Isotopes Environ Health Stud 38: 227-243.

- Alho C, Júnior T, Campos Z, Gonçalves H (1987) Mamíferos da Fazenda Nhumirim, sub-região de Nhecolândia, Pantanal do Mato Grosso do Sul. I. Levantamento preliminar de espécies. Rev. Bras. Zool 4: 151–164

- Nunes A (2011) Quantas espécies de aves ocorrem no Pantanal brasileiro? Atualidades Ornitológicas On-line N° 160.

- Ito F, Vasconcellos S, Bernardi F, Nascimento A, Labruna M, et al. (1998) Evidência sorológica de brucelose e leptospirose e parasitismo por ixodídeos em animais silvestres do pantanal Sul-matogrossense. Ars Vet 14: 302-310.

- Bechara GH, Szabó MP, Duarte JM, Matushima ER, Pereira MC, et al. (2000) Ticks associated with wild animals in the Nhecolândia Pantanal, Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci 916: 289-297.

- Sangioni LA, Horta MC, Vianna MC, Gennari SM, Soares RM, et al. (2005) Rickettsial infection in animals and Brazilian spotted fever endemicity. Emerg Infect Dis 11: 265-270.

- Gwynne JA (2010) Aves do brasil: Pantanal & Cerrado [translate Martha Argel] Comstock Publishing Associates -São Paulo: Editora Horizonte, São Paulo, Brazil.

- Sigrist T, Eduardo P. Brettas (2009) Guia de Campo Avis Brasilis - Avifauna Brasileira: Pranchas e Mapas: The Avis Brasilis Field Guide to the Birds os Brazil, Bruna Lugli Straccini(translator), Avis Brasilis, Brazil.

- Sigrist T (2009) Guia de Campo Avis Brasilis - Avifauna Brasileira: Descrição das Espécies: The Avis Brasilis Field Guide to the Birds os Brazil: Species Account / Tomas Sigrist, translated by Bruna Lugli Straccini; illustred by por Tomas Sigrist e Eduardo P. Brettas. São Paulo: Avis Brasilis, Brazil.

- Nunes A, Tomas W (2004) Aves migratórias ocorrentes no Pantanal: Caracterização e conservação. Corumbá: Embrapa Pantanal, Documentos / Embrapa Pantanal, ISSN 1517-1973; 62

- Wilson DE, Reeder DM (2005) Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. (3. Ed) John Hopkins University Press 1: 312-529, Baltimore,US.

- Magnusson W, Llima A, Luizão R, Costa F, Castilho C, et al. (2005) Uma modificação do método de gentry para inventários de biodiversidade em sítios para pesquisa ecológica de longa duração. Biota neotropica 5

- Pitarelli A, Pereira M (2002) Dieta de aves na região leste do Mato Grosso do Sul. Ararajuba 10:131-139.

- Alekseev AN, Dubinina HV, Semenov AV, Bolshakov CV (2001) Evidence of ehrlichiosis agents found in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from migratory birds. J Med Entomol 38: 471-474.

- Santos-Silva MM, Sousa R, Santos AS, Melo P, Encarnação V, et al. (2006) Ticks parasitizing wild birds in Portugal: detection of Rickettsia aeschlimannii, R. helvetica and R. massiliae. Exp Appl Acarol 39: 331-338.

- Spitalská E, Literák I, Sparagano OA, Golovchenko M, Kocianová E (2006) Ticks (Ixodidae) from passerine birds in the Carpathian region. Wien Klin Wochenschr 118: 759-764.

- Heylen D, Adriaensen F, Van Dongen S, Sprong H, Matthysen E (2013) Ecological factors that determine Ixodes ricinus tick burdens in the great tit (Parus major), an avian reservoir of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. Int J Parasitol 43: 603-611.

- Santos LG, Melo AL, Moraes-Filho J, Witter R, Labruna MB, et al. (2013) Molecular detection of Ehrlichia canis in dogs from the Pantanal of Mato Grosso State, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 26:0

- Massung R, Slater K, Owens J, Nicholson W, Mather T, et al. (1998) Nested PCR assay for detection of granulocytic ehrlichiae. J Clin Microbiol 4: 1090-1095.

- Chae J, Kim E, Kim M, Kim M, Cho Y, et al. (2003) Prevalence and sequence analyses of Neorickettsia risticii. Ann N Y Acad Sci 990: 248-56.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15196

- [From(publication date):

October-2013 - Jul 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10545

- PDF downloads : 4651