A Token Economy: An Approach used for Behaviour Modifications among Disruptive Primary School Children

Received: 01-Jan-1970 / Accepted Date: 01-Jan-1970 / Published Date: 30-Jun-2018 DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000398

Abstract

Introduction: For decades, academic and non-academic researchers have been examining the issue of school-based violence, especially disruptive behaviour exhibited by students including those at the primary level. Despite the plethora of studies and intervention programmes implemented in school including Peace and Love in Schools (PALS), bullying, physical confrontations, and other types of disruptive behaviours are on the rise, and there appears to be no ending in sight.

Objective: This research seeks to examine and determine the impact that the token economy system as a behaviour modifier has on disruptive behaviour in classrooms among a group of primary level students in the parish of Manchester, Jamaica.

Methods: This study employed mixed methodologies (i.e. objectivism (survey research) and subjectivism (phenomenology) in an effort to comprehensively understand the phenomenon. The sample size is 40 students; 21 girls and 19 boys, and the classroom teacher. These students exhibited behaviours which disrupted the teaching and learning process. This has created a problem within our classrooms. In order to alleviate this problem an eight weeks’ intervention plan was carried out. During this intervention plan an observational checklist, a teacher’s questionnaire and a teacher’s journal were used to collect data. The results were presented to show a review of the use of the token economy in the school environment using figures, tables, and charts.

Findings: The results revealed that students’ behavioural levels after the intervention showed evidence that the use of tokens in minimizing disruptive behaviour was very effective. Fewer warnings were given and more time was spent instructing students to participate in meaningful class activities. This resulted because disruptive behaviour such as frequent requests for bathroom breaks decreased to 23%, disorderly conduct decreased to 40%, fighting levels decreased to 5%, talking in the class decreased to 40%, joking in the class decreased to 10%, quarreling in the class decreased to 13% and eating in the class stopped completely. The use of the tokens also had a positive impact on the students’ academic performance, and helped in creating a more positive relationship between students and teacher and student and student. This resulted because the levels of disruptive behaviours decreased which allowed for the transformation from a tense and hostile classroom; to a classroom where students have more chances to freely express themselves and receive feedback. It can be deduced from the results that the extensive implementation and evaluation of the use of the token economy was an effective way of decreasing disruptive behaviours among a group of primary school students in the classroom.

Conclusion: The use of token economy should be a strategy that is employed in the teaching-learning process as a medium of increasing academic performance and decreasing disruptive behaviours.

Keywords: Classroom management; Coaching; Disruptive behaviour; Leadership; Token economy

Introduction

Effective classroom management strategies can help teachers with an important issue that may hinder the learning and teaching process, which is students’ disruptive behaviour. According to Deering (2011), disruptive behaviour is defined as any behaviour that is disrespectful, annoying or distracting, wastes class time, or generates negative attitude towards the course or instructor. Rose and Gallup (Oliver, Wehby & Daniel, 2011), stated that disruption is seen as the most common request for assistance from teachers that is related to behaviour and classroom management. Disruptive behaviour directly puts teachers, children, and parents in embarrassing situations. In the teaching and learning environment teachers have to ensure that the learners have their fundamental rights to have a safe and respectful environment for learning. Therefore, it is imperative for educators to explore sources, put their heads down, and think of effective strategies that will reduce and help with the coping of such behaviour in order to protect their students’ future.

Kauffman (Oliver, Wehby & Daniel, 2011), argued that a child’s behaviour is shaped by the social context of the environment during the development process. Kauffman, Patterson, Reid and Dishion (Oliver, Wehby & Daniel, 2011), also argued that many behaviour problems begin or are made worse through behavioural processes such as modeling, reinforcement, extinction, and punishment. The challenge for educators therefore, is to make changes to the learning environment in order to decrease disruptive behaviour. If these changes are effective, it will result in an increase in academic performance as well as allow students and faculty to enjoy a respectful, inviting, healthy, and productive learning environment.

Hunger for such a learning environment has taken over the education sector in Jamaica and other countries to search for ways to reduce the occurrences of disruptive behaviour in the classrooms. These searches have found the use of token economy to be a highly effective strategy in decreasing disruptive behaviour. Being aware that disruptive behaviour poses a threat to the teaching and learning environment, our concern is steeped in the reality that something needs to be done to help in reducing disruptive behaviour within the classroom. This study is concerned about the negative effects it has on both teachers and students whether it be physical, mental or emotional. It is of grave concern as it poses a deep and severely abiding setback in the education system and if something is not done to reduce or eliminate such a problematic scourge, student academic outcomes will continue to suffer and deteriorate progressively and the academic level will experience a great decrease.

Background

One of the researchers in this study, while on a three-week practicum at a primary school located in Manchester, was assigned to a grade two class. The population of the class was approximately forty students and the school’s population was about seven hundred students. While teaching at the school, the researchers noticed how disruptive the students were which often resulted in poor and ineffective delivery of some lessons.

The students were disruptive for over 60% of the time assigned to each lesson on a daily basis. For most parts of the lessons, some students were talking, others were moving about the classroom and some were busy making toys with paper torn from their notebooks. Students were constantly on their feet sharpening their pencils and conversing with their peers about topics which were not related to the lesson being taught. The girls would talk about such things as lip gloss and the boys would debate about thinks like whose cartoon character looked the best.

Students who made toys, such as planes, threw them across the classroom hitting their classmates repeatedly. This usually resulted in the development of arguments and fights. During these arguments, students shouted indecent words at each other in raging temper and threw several punches and slaps to the body and limbs of each other. Other fights also developed because of bullying and random troublemaking. Students were bullied for their stationaries and food. Fights resulting from this were most disruptive. One such fight resulted in the bleeding of the nose of a male student. One specific student in the class, during lessons, would walk around the class quietly and make trouble by spitting on the other students. He would also destroy teaching aids made by the teacher for the effective delivery of the lesson. He did this in three ways: he would tear them into pieces, he would stomp on them, or he would bite them and swallow the pieces.

It is obvious that disruptive behaviour retards the effectiveness of the teaching process and also impedes the learning of the students and their classmates. This required immediate attention and appropriate use of strategies to eliminate or decrease such behaviour which worsened as time passed. Furthermore, attempts to control disruptive behaviour costs considerable teacher time at the expense of academic instruction.

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of early intervention on disruptive behaviour of students using a token economy. This study was to discover the different types of student disruptive behaviours as viewed by teachers of elementary schools in Jamaica and to find out the causes of disruptive behaviour in classrooms. Becoming aware of the causes of disruptive behaviour and making the necessary changes, will improve academic performance as students will make efforts to be honest and show respect for themselves, classmates, and teachers. At the end of this study we would like disruptive behaviour to be decreased and see improvement on task performance in relation to academic performance through the use of token economy systems. Hence, this study will examine the following research questions: 1) what were the dominant disruptive behaviours prior to the intervention? 2) How did the boys respond to the use of the token economy? 3) How did the girls respond to the use of the token economy? and 4) What were the dominant behaviours after the intervention?

Conceptual Framework

Children attend school to become educated members of the society, capable of making informed decisions and increasing future career possibilities. Some children have found it difficult to adjust to the classroom environment and as a result act out by becoming disruptive. Literature was reviewed from a global and local perspective which highlighted the history of the token economy as it relates to disruptive behaviour, causes of disruptive behaviour, and the advantage and disadvantages of using token economy to help in reducing such unwanted behaviour within the classrooms.

As early as the 7th century, token systems were used as rewards by monks and by educators as incentives for learning. As several centuries past, modern forms of the token economy have been increasingly used in the education society. Two of these modern forms of the token economy system came about in the 1800’s. They are called the Monitorial System and the Excelsior System. Kazdin (1977) stated that the Monitorial system involved teacher helper; they made it easier for teaching large groups and the Excelsior system consisted of giving out “excellents” and ‘perfects” designations to students for pro-social and pro-academic behaviours. With both of these systems, prizes and rewards acted to make the token system more powerful in affecting behaviour.

Throughout the last several decades, teachers and caretakers have used these systems in general education, special education, and community-based settings (Doll, McLaughlin & Barretto, 2013). Disruptive behaviour can have negative effects on not only the classroom environment but also on the school experience as a whole. As a result of this, it is only natural that the school will have to devise the ways and means of effectively managing disruptive behaviours so that those involved can learn and develop from the experience. Token economies have been one of the most effective ways to improve classroom behaviours (Higgens, Williams & McLaughlin, 2001).

Token economy systems are able to have a profound impact on schools, classrooms, and community-based setting. Token economies are often used for individual students but class wide programmes are also used at times (Filcheck, McNeil, Greco & Bernard, 2004). Tokens are most often a neutral stimulus in the form of points or tangible items which are awarded to economy participants for a targeted behaviour. Miller & Drennen (1970) noted that token economy gained its utility and power to modify behaviour when the neutral token becomes a secondary reinforcer.

Misbehaving learners and disciplinary problems are a disproportionate and intractable part of every teacher’s experience of teaching (Marais & Meier, 2010). Providing teachers with skills and strategies to manage disruptive behaviour effectively in the classroom is essential as the classroom can be a contributory factor to the occurrence of disruptive behaviour particularly to the frequency and severity of such behaviours. O’Leary & Drabman (1971) posited that a less confronting, easier, and more positive means of managing disruptive behaviour in the classroom is the token economy.

A well-organized classroom allows more positive interaction between the teacher and his or her students and limits the possibility of disruptive behaviour occurring in the teaching and learning process. However, when a learner presents with disruptive behaviour, the teacher has to view the behaviour within the context of the learner’s life and come to an understanding of the forces that shape the life of the learner. This understanding requires solid “background” knowledge of child development, the reasons why learners behave and misbehave, and which types of disruptive behaviour occurs most frequently in the classroom. A token economy can help overcome some of the difficulties associated with assisting classroom participation. Furthermore, (Nelson, 2010), opined that modifying the classroom environment serves as an intervention for children who exhibit disruptive behaviour and who may be at risk. Boniecki & Moore (2003) also reported that the use of the token economy with regards for correctly answering questions had multiple benefits. This has acted to create restriction of the range to which problems might develop.

A relationship-building approach helps the students develop positive, socially appropriate behaviours by focusing on what the student is doing right, (Hall, 2003). According to Mabebe and Prinsloo (as cited in Morais & Meier, 2010), disruptive behaviour is attributed to disciplinary problems in schools that affect the fundamental rights of learners to feel safe and be treated with respect in the learning environment.

Commonly arising disruptive behaviours such as talking out of turn and name calling are called surface behaviour because they are usually not a result of deep-seated personal problems. However, more serious disruptive behaviour such as conflict which results into physical violence is most challenging to deal with. Common reasons why students misbehave in the classroom are as a result of inexperience or ignorance, curiosity, need for belonging, need for recognition, need for power, control and anger release. Reasons outside of the classroom are factors related to the family and society, (Morais & Meier, 2010).

Chen & Ma (2007) noted that disruptive behaviour is closely related to less academic engagement, low grades, and a poor performance on standardized test. Filcheck & McNeil (2004) suggested that for teachers to manage children’s behaviour as well as teach academic readiness and social skills, a classroom behavioural management system should be simple to implement and use in order to allow the teacher to conduct his or her class without major disruption.

Tiano, Fortson, McNeil & Humphery (2005) suggested that if teachers attend to appropriate behaviours and provide social rewards for those behaviours it could promote a more positive atmosphere in the classroom. With the use of the token economy appropriate child behaviour should increase as those behaviours are receiving reinforcement from teacher. Chance (2009) stated that any form of reinforcement whether positive or negative actually strengthens behaviour. For example, Filcheck & McNeil (2004) advised that giving a warning to a student who exhibits a mildly negative behaviour or exhibits a highly negative behaviour, such as hitting a peer can help with reducing disruption.

A study by Zlomke & Zlomke (2003) showed that a token economy can significantly improve behaviour but when paired with a self-monitoring aspect can even further increase appropriate behaviours in children. A token economy is more effective for targeting certain behaviours, such as completion of task or reduction of inappropriate behaviours, the effectiveness of a class-whole token economy versus an individual programme, and whether a self-monitoring aspect to a token economy can increase or decrease the effectiveness of the programme. Selfmonitoring involves the student marking their own behaviour, positive or negative, and consulting with a teacher to verify the responses (Zlomke & Zlomke, 2003). It also involves the student having his own card to record his appropriate behaviour during the periods. The student earned an extra point per period if his records matched the teacher’s record. After the token economy plus selfmonitoring condition was implemented, because the student earned an extra point, another token economy for the additional student improvement was implemented.

Kohn (2005) stated that reward systems, such as token economies, create controlling environments, decrease children’s self-esteem as children begin to believe that they only are behaving for external reward, and not because they like what they are doing. Filcheck & McNeil (2004) mentioned several disadvantages of individual token economies being used in a classroom. One disadvantage is that teachers may have difficulty keeping track of each system and without enough staff members it could interfere with instruction. Another disadvantage is that the students who do not have token economies may feel left out or their parents may object to their children not receiving that attention. Lastly, if only certain students have token economies this can make them more noticeable to other students and increase isolation.

Methodology

The methodology of this research is encapsulated in this section of the paper. This section of the paper deals with the methods, designs, and techniques that were used to answer the research questions. This action research involved the sample, data collection tools, a procedure and the ethical issues which were all used in an attempt to gain an understanding of the existence and nature of attitudes, interest, and opinions as it relates to the use of token economy to reduce disruptive behaviour in the classroom. An action research is a form of investigation designed for use by teachers to attempt to solve problems and improve professional practices in their own classrooms. Sagor (2000) says that action research “is a disciplined process of inquiry conducted by and for those taking the action. The primary reason for engaging in action research is to assist the ‘actor’ in improving and/or refining his or her action”. It involves systematic observations and data collection which can be then used by the practitioner-researchers in reflection, decision-making and the development of more effective classroom strategies (Parsons & Kimberlee, 2002).

Sample and Participants

The sample selected from the school population was one of two grade two classes. This class was selected to participate in the study as they showed the worst pattern of disruptive behaviour. The study was conducted in a second grade class with one teacher and the entire class of forty students. The ages of the students ranged from seven to ten years old. The sample size for this research consisted of nineteen boys and twenty-one girls. These participants were from a middle to low socioeconomic background neighbourhood in Manchester. Darling (2007) posits that knowledge of others cultures broadens perspective of diversity in the classroom. Also included in this study is the principal.

Data Collection Tools

The sample was a grade two class from a primary school in Manchester. The sample selected was a convenient sample because the access to the participants was readily available. To ascertain data for this action research, the researchers used three data collection tools: a teacher’s questionnaire, observational checklist, and teacher’s journal. The teacher journal was used to provide a reflective account based on observation and interpretation of events. The observational checklist was used to observe students in their normal environment and the questionnaires to gather various reasons for behaviour patterns in individuals and groups. The data gathered and entered and stored in Windows for Excel. Afterwards, the data were analysed, graphs and tables were presented with percent to provide values for mathematical computations.

Questionnaire

Questionnaires are instruments used for collecting data in survey research. They usually include a set of standardized questions that explore a specific topic and collect information about demographics, opinions, attitudes, or behaviors (Elliott, 1988). The researchers used the questionnaire because they wanted to find out how the students feel in the class environment, what type of relationship they have with their peers and the teacher. They also wanted to know from the classroom teacher if this strategy has ever been implemented with these students. This was administered at the beginning of the study where students were asked questions one on one and a typed questionnaire was given to the teacher. Each student was asked a total of five questions and the class teacher was asked about ten questions (See Appendix A for teacher questionnaire).

Observation Checklist

According to Elliott (1988) the best way to collect data is through observation. Observational checklist is also defined as a simple list of criteria that can be marked as present or absent, or can provide space for observer comments. These tools can provide consistency over time or between observers. This tool was chosen because it can be done directly or indirectly with the participants knowing or being unaware that they are being observed. This checklist had eight criteria (See Appendix B for observational checklist). This tool was used at the beginning of the study and at the end of the study on the last day in the seventh week.

Teacher’s Journal

A teacher’s journal is used to document all that is observed by students during the implementation (Singer & Maher, 2007). The researchers observed and noted whether there was an increase in the student’s targeted behaviour, a reduction in students talking out of turns, and if students were making an effort to build positive relationships among peers and teacher. The researchers also noted their body language and their responses. This was used at the beginning of the study, throughout the study, and at the end of the study.

Procedure

This action research was conducted in a grade two class over an eight-week period. In order to conduct this action research smoothly, a plan of action which shows weekly intentions had to be constructed.

Week One

In the first week upon arrival at the school, the researchers presented a letter to the principal from whom permission was sought to carry out this research for eight weeks. Following a brief meeting with the principal, outlining the nature and parameters of the study, the principals granted permission for the research to be conducted. The researchers then met with the classroom teacher, stated and clarified the purpose of the study as well as ascertained additional guidance in constructing permission letters which were given to the students to take home in order to get permission from their parents or guardians (See Appendix C for Parent Consent Letter). The permission letters were later collected and checked if they were duly signed by parents. The students were then invited to join the researchers in setting the ruled of conduct and stated target behaviour. Information was then gathered to compile criteria for the observational checklist.

Week Two

The researchers made formal contact with the class and had the students placed into groups. Each group was told what the research entailed. They were informed about the kind of intervention that will be made and how the data for the research will be collected. The participants were told that they will be encouraged for their participation and behaviour during the period of the research. The classroom teacher was given the teacher’s questionnaire for completion and the students were asked questions to help in the completion of the first checklist.

Week Three

The researchers began to ascertain the students’ specific behavioural problems and the situations in which they occurred to modify the observational checklist. Throughout this time the students were observed in their natural environment on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 12:00 to 2:30 pm. Behavioural problems and the effects they had on the learning process were documented.

Week Four

The researchers conducted regular class routines and stopped at appropriate intervals to point out students who showed appropriate classroom behaviours. Other students were taught how to behave in the classroom to create a positive classroom climate.

Week Five

The researchers explained the appropriate behaviours to the students so that a better understanding of what was expected of them to preserve the positive changes could be reinforced. Motivational charts were posted around the classroom with positive messages as reminders of positive behaviours. The observed changes were documented as they occurred.

Week Six

The researchers modified the classroom environment to remedy undesired behaviour by rearranging desks and class duties. Token economy was used as a reinforcement strategy to encourage students who exhibited positive behaviour and the targeted behaviour. Students were given small tokens whenever they displayed appropriate behaviour. Improvements were documented through observation. The changes were continuously observed and documented as they occurred.

Week Seven

During this week the researchers started to phase out the intervention. The final observational checklist was completed and documented to note the effectiveness of the strategy at this stage.

Week Eight

The researchers reviewed personal notes taken and made a comparison between the two checklists. An evaluation was done with both the teacher and the principal to provide appropriate feedback.

Definition of Terms

Disruptive Behaviour

Deering (2011) disruptive behaviour is defined as any behaviour that is disrespectful, annoying or distracting, wastes class time, or generates negative attitude towards the course or instructor.

Token Economy

Matalon (2008) defined token economy as a contingency: tokens are given as soon as possible following the emission of a target response. The tokens are later exchanged for a reinforcing object or event.

Classroom Management

Matalon (2008) described classroom management as all the teacher behaviours that lead to the creation of an orderly classroom environment and promotes learning.

Direct Observation

Is a way of gathering data by watching behaviour, events, or noting physical characteristics in their natural setting (Powell & Steele, 1996).

Behaviour Modification

This is the term used to describe different behaviour change techniques to increase or decrease the frequent display of a behaviour (Matalon, 1998).

Positive Reinforcement

Skinner (1938) defined positive reinforcement as a method of strengthening behaviour by providing a consequence an individual finds rewarding.

Ethical Consideration

The students who participated in the research, their parents or guardians, and the principal of the cooperating school were briefed about our intentions to conduct this study. They were all informed about our use of observation, questionnaires and journaling as methods of collecting data.

The participants were reassured that the data gathered will be treated with the highest level of confidentiality. With respect to the questionnaires that were used to gather the reasons for student behaviour, care was taken to ensure their names were protected from any kind of exposure. Students were made aware that their participation in the study was not mandatory and that there will be no punishment if they choose not to participate in the study.

Findings

This survey was achieved through an eight-week intervention plan among a class of 40 students at a primary school in Manchester. These students exhibited disruptive behaviour in the class which created barriers to other students’ achievement. Because of these barriers most of the time reserved for the teaching and learning process was taken up with non-instructional activities such as tokens, in an attempt to decrease disruptive behaviour. From the activities, data was collected and used to answer four sub-research questions. The methods used to collect the data were teacher journal, observational checklist, and teacher’s questionnaire shown in Table 1.

| Research Sub-question | Questionnaire | Observational Checklist | Teacher’s Journal |

|---|---|---|---|

| What were the dominant disruptive behaviour prior to the intervention? | |||

| How did the boys respond to the use of the Token Economy? | |||

| How did the girls respond to the use of the Token Economy? | |||

| What were the dominant disruptive behaviour after the intervention? |

Table 1 : Triangular Matrix of Data Collection

Question 1. What were the Dominant Disruptive Behaviours Prior to the Intervention?

The results for this question were attained using an observational checklist and a teacher’s journal during the first three weeks of the intervention plan.

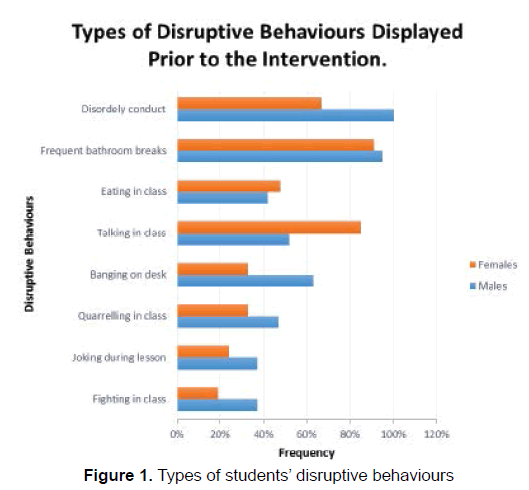

Figure 1 shows the different types of behaviours exhibited by the grade two students prior to the intervention. The students were observed to determine the criteria for the checklist then further observed to gather information which was used to complete the observational checklist.

The observational checklist revealed that 52% of the males were always talkative during the lesson, while 85% of the females displayed the same behaviour. 37% of males and 24% of the females were constantly making jokes during the lesson. There were frequent cases of quarrelling in the class among 47% of the males and 33% of the females were observed doing the same. Resulting from these quarrels at times were fights between malesmales, males-females, and females-females. 37% of the males often fought and 19% of the females did the same. Disorderly conduct was the most disruptive of all followed by the request of bathroom breaks. One hundred percent of the males and 67% of the females for the most part of the lesson behaved inappropriately. 95% of the males wanted to visit the bathroom to play, while the same was true for 91% of the females. Other playful but very disruptive activities the students took part in was banging on the desk during the lesson. This was evidence found amongst 63% of the males and 33% of the females. Forty-two percent of the males and 48% of the females were frequently caught eating in the class.

The teacher’s journal that was used to document all that was observed in a class of 40 students; 19 males and 21 females contains the disruptive behaviours they exhibited. The disruptive behaviours observed and noted were banging on the desk, interrupting instruction, excessive chattering, and roaming the classroom. This was common to both males and females. The females however, were noted as more disruptive as they interrupted instructions to makes complaints very often.

Question 2. How did the Boys Respond to the Use to the Token Economy?

The results for this question were assembled using a teacher’s questionnaire and a teacher’s journal from the fourth week of the intervention plan to the seventh week.

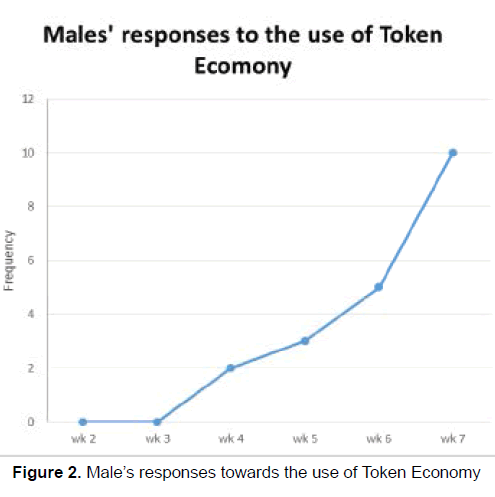

Figure 2 demonstrates the observed changes in the behaviour of males toward the use of the token economy. During the second and third week of the intervention no change was observed in the behaviour of the males. However, through the use of tokens such as stickers, their academic performance improved. Changes became evident in the fourth week of the intervention. Two of the males were the first male students that responded positively to the tokens. These males were more cooperative and showed little signs of regrets for the disruptive behaviour they exhibited.

Week 5 showed a slight decrease in the amount of males who were disruptive. An addition of one male student making it a total of three students showed positive response to the use of the tokens. These males were observed for weeks and were assumed to be close friends. All three males displayed similar results as observed in week 4 but they also showed that they were somewhat more attentive.

During week 6, five more males were identified and noted as positive responders to tokens. They interrupted instructions less, cooperated in class activities without distracting other pupils and participated less in the banging of the desks.

By week 7 achieving a token for the boys became a competition which resulted in an increase to ten males who became less disruptive. These males were more attentive, cooperative and distracted other pupils and instructions 0%-3% less during class period.

The teacher’s questionnaire revealed the effectiveness tokens have had on the students when used in previous situations. The response from the teacher’s questionnaire disclosed that the use of incentives tends to work with only a certain population of the class. In responding to the question, the teacher further explained that where mitigating disruptive behaviour is concerned, incentives normally work well with pupils who are intrinsically motivated as well as more advanced.

Question 3. How did the Girls the Use to Respond the Use of the Token Economy?

The results for this question were collected using the methods, teacher’s journal and teacher’s questionnaire during weeks 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

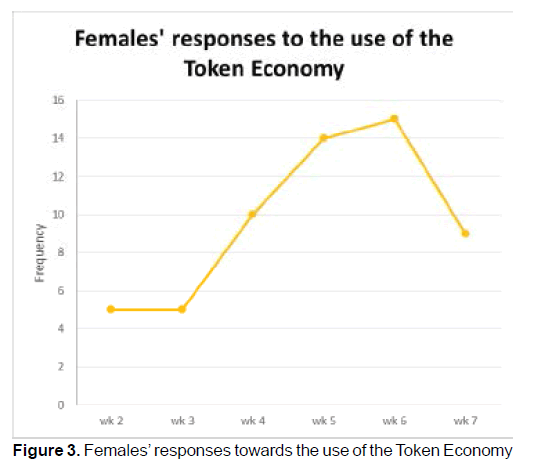

The results presented in Figure 3 were displayed by the female population of the class. After the initiation of the intervention of tokens a decrease of 1% or 5 females was observed in the second week through to the third week. These 5 female students were less talkative and a bit more attentive. As the week progressed, by week 4 there was an immense increase in the number of female students who responded positively to the tokens. Ten of females showed a reduction in the level of chattering, interrupted the class less to request permission for bathroom breaks and cooperated more willingly in group activities. By week 5, 66% or 14 females’ involvement in quarrels and other disorderly conducts decreased significantly as a result of changing in seating arrangements. In the course of week 6 a slight increase was observed in the improvement of the females’ behaviour. Their attitudes had changed. This was seen in 71% or 15 of the female students. However, in week 7 the females became unresponsive to the tokens. Fifteen females were observed as less disruptive; they responded positively to the strategy Token economy in week 6 but a setback was noted in the seventh week where only 43% or 9 females were now responding positively to the use of the token economy. Six of the formerly less disruptive female students now demonstrated behaviours which were interruptive. They re-engaged in quarrels, excessive chattering and started to interrupt instructions to make complaints once more.

One of the questions listed on the teacher’s questionnaire read, what is the outcome of using incentives and how does it impact students who exhibit disruptive behaviour. The reply was that the population of the class which exhibited disruptive behaviours continued to do so even if the strategy token economy is used. The response that was given is similar to what was observed in week 7 of the intervention.

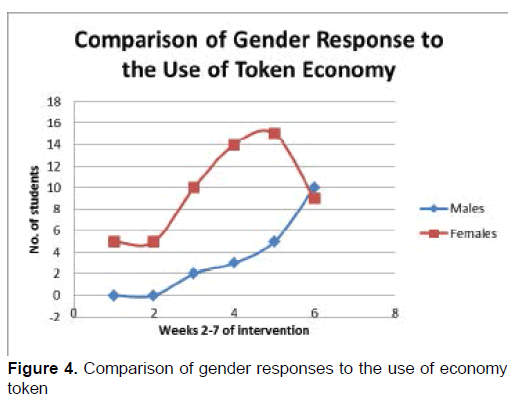

At the initial stage of the intervention plan the females responded quickly and positively to the use of the tokens shown in Figure 4. The decrease in their disruptive behaviour was consistent from the second week through to the sixth week. However, upon approaching the seventh week, the females showed signs that they reverting to being disruptive. This was evident as the numbers decreased from 15 to 9. At week six, 15 females were responding positively to the token economy. This fluctuated to 9 females by week seven.

The males on the other hand responded slowly to the use of the token economy. However, as time progressed they started to change their behaviour which was favourable to the researchers’s intension of the survey; to decrease disruptive behaviour using token economy. The behaviours were observed to be decreasing in the males from week four consistently throughout to week seven which continued until the intervention was phased out. From this observation it can be concluded that the males responded more positively to the use of tokens to decrease disruptive behaviour in the class.

The information gathered from the teacher’s questionnaire suggested reasons for the fluctuation in the females’ progress and the slowed reaction of the males toward the token economy system. It was opined that this could probably be the result of the class size; student teacher ratio, student being academically challenged, lack of parental involvement, nutrition, and exposure to inappropriate social upbringing.

Question 4. What were the Dominant Disruptive Behaviours after the Intervention?

The results for this question were collected using an observational checklist and a teacher’s journal.

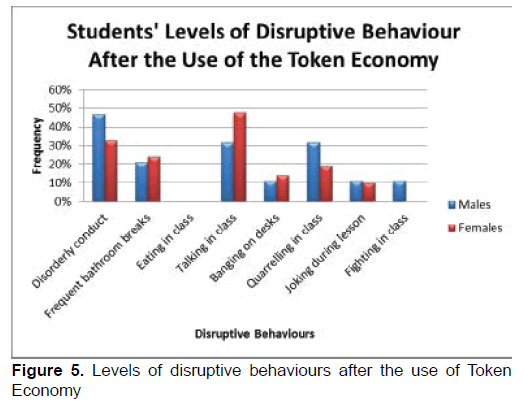

Figure 5 reveals the students’ behaviour after the intervention plan was implemented for a period of seven weeks. After the completion of the second checklist various changes were observed in the students’ behaviour. After the use of the tokens only 32% of the males and 48% of the females continued to talk during the lesson. The levels of joking during the lesson decreased. This was now done by 11% of the males and 10% of the females. Quarrelling in the class among the males decreased to 32% and the same was observed for 19% of the females. As a result of the reduction in the occurrence of arguments came a reduction in the number of fights. Zero percent of the females fought and only 11% of the males still fought in the class. Fewer students participated in the activity of banging on the desks. This number of students who participated in such activity decreased to 11% of the males and 14% of the females. Another impressive change was observed in the students’ conduct, where only 47% of the males and 33% of the females still proceeded to behave in a disorderly manner. The token Economy was observed to have the most impact on the disruptive behaviour of eating in the class, because after the intervention 0% of the males and 0% of the females participated in such activity. The frequent request to go to the bathroom decreased to 21% of the males and 24% of the females.

The changes that were noted reflected that which were observed and presented on the checklist. Some disruptive behaviours were somewhat still dominant after the intervention of the Token Economy. These behaviours included talking and joking during the lesson, quarrelling and fighting in class, banging on the desks, students conducting themselves in a disorderly manner, and asking to go to the bathroom.

Talking and joking in the class took place for the first one to two minutes while the teacher wrote the assessment. Quarrelling and fighting happened among the sample still however, which was observed on the corridors and on the play grounds. The banging on the desks decreased, but still happened from time to time. Whenever it happened, the students seemed to have done it out of excitement and often made apologies following such an act. Disorderly conduct such as shouting across the class and wondering around the class while instructions are being given decreased significantly. Students also asked to visit the bathrooms less because they no longer went out in pairs or groups.

Table 2 compares the data collected prior to and after the use of the Token Economy strategy. Prior to the intervention the students’ disruptive behaviour made it difficult for the teacher to give instructions. However, after the intervention a decrease in the students’ behaviour was observed.

| Disruptive Behaviours | No. of students | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Talking in class | 10 | 18 | 6 | 10 |

| Joking in class | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Quarrelling in class | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 |

| Banging on desks | 12 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| Disorderly conduct | 19 | 14 | 9 | 7 |

| Fighting in class | 9 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Eating in class | 8 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Frequent bathroom breaks | 18 | 19 | 4 | 5 |

Table 2: Comparison of the students’ behaviours prior to the intervention and after the intervention

At the initial stage of the intervention 10 males were observed as too talkative. This decreased to 6 males after the intervention. Eighteen females displayed similar behaviour which decreased to 10 females by week seven of the intervention. Seven males were always joking during the lesson before the intervention. This was lowered to 2 males after the use of tokens. There were 5 females who took part in the same disruptive activity of joking in the class but like the males after the use of tokens it decreased to 2 females. Quarrelling in the class among males decreased from 9 to 6 and among females it decreased from 7 to 4. The interruptive behaviour of banging on the desks also decreased for both males and females. Before the intervention 12 males and 7 females participated in such activity but after the intervention, this decreased to 2 males and 3 females. Changes were also observed in the way the students conducted themselves in the classroom. Nineteen males and 14 females conducted themselves in a disorderly manner before the intervention. However, after the intervention the number of students who displayed this behaviour decreased to 9 males and 7 females. The use of the Token Economy had the most impact on the disruptive behaviours of fighting and eating in the class. Fighting was dominant among 9 males and 4 females. This later decreased considerably to 2 males and 0 females. Eight males and 10 females were always eating in class prior to the intervention of the Token Economy strategy. This behaviour was no longer demonstrated by any of the students after the intervention plan. Eighteen males and 19 females always requested permission to go to the bathroom but with the intervention plan after several weeks this disruptive behaviour decreased to 4 males and 5 females.

Limitations

While conducting this research a few issues revealed themselves which might have affected the result and findings of the true effect the token economy system might have had on curtailing disruptive behaviours in the classroom. These issues included: firstly, attempting to review as much literature to compile the research which might have resulted in overlooking important information. Secondly, students were observed for the most part in one specific class which made the findings impossible to generalize the population from which the sample was taken. Thirdly, changes observed in the students behavioural patterns might not have resulted because of the use of the tokens. Lastly, the research was conducted in a short time.

Discussion, Recommendation and Conclusion

It is apparent that disruptive behaviour in the classroom is one of the major challenges that teachers face. This was observed in a primary school located in Manchester in a grade two class of 40 students; 19 boys and 21 girls. These students displayed various types of disruptive behaviours which negatively impacted the teaching and learning process. Having observed the negative impact disruptive behaviour has on the educational system and the society on a whole, the research aimed to determine how effective the use of token economy is in decreasing disruptive behaviour in the classroom. The research made use of three data collection tools to gather data over a period of eight weeks. The data collection tools used were an observational checklist, a teacher’s journal, and a teacher’s questionnaire.

The results of the study awakened a number of interesting findings. These interesting findings were used to answer the subresearch questions:

1) What were the Dominant Disruptive Behaviours Prior to the Intervention?

Before initiating the intervention plan, unstructured observation revealed that students had poor or disruptive behaviour problems before venturing in the school environment but did not receive the benefits of early intervention. These students frequently exhibited inappropriate behaviours such as eating in the class, talking out of turn, banging on the desks, quarrelling in the class, fighting in the class, and joking during the lesson. The males were observed as frequent partakers in disruptive activities such as fighting and banging on the desk during lessons. Observation also revealed that the females displayed behavioural problems such as talking and eating in the class more frequently than the males. This seriously hindered their ability to be successful in their achievements.

Additional note taking and documenting showed that these disruptive behaviours were influenced by the students’ communities and homes. These students modeled the behavioural patterns and attitudes which they observed from members within their communities and socialized in a similar way they were communicated to in their homes by their parents. This supports the common saying, “the apple does not fall far from the tree”. Therefore, it can be said that the child’s surroundings play a valid role in shaping the child.

2) How did the Boys Respond to the Use of the Token Economy?

The results of this study showed that the introduction of the token economy decreased the disruptive behaviours of the students. Prior to the intervention the boys frequently exhibited inappropriate behaviours such as fighting, banging on the desk, and other disorderly conducts. The occurrences of these inappropriate behaviours were significantly reduced with the use of the token economy. This reduction was observed from the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh week of the intervention where two then three then five and the ten males started to respond positively towards the use of the token economy respectively. Not only was there improvement in the male’s behaviour but there was a significant arousal of their interest in wanting to participate in class activities. This made the teaching and learning process less hassling.

The teacher questionnaire asked how effective the use of the token economy system was as it relates to reducing the occurrences of disruptive behaviours in the classroom. The teacher’s response was that tokens tend to work with a certain population. Observation and findings proved that the tokens had a positive impact on the males who appeared to be from a more stable home and those who were intrinsically motivated.

3) How did the Girls Respond to the Use of the Token Economy?

The results of the study also showed that the females responded quickly and positively to the tokens. The females displayed different behaviours in response to the use of the token economy system. During weeks two and three a small fraction of the sample size was observed and noted to be more cooperative and attentive in class. In weeks four, five and six more females started to respond positively toward the use of tokens with week six recorded as the most successful. A total of fourteen females were observed to be cooperative, attentive, interested, and motivated in the class activities. However, there was a fluctuation in the process made. This was observed in week seven where six of the females started to behave disruptively once more. Besides the minor setback, fewer time was spent curtailing the students behaviour and more time was spent on engaging the students in more meaningful activities. This created an atmosphere which allowed for positive interaction and as a result limited the recurrence of disruptive behaviour during instruction.

The questionnaire revealed the outcome of using incentives and how it impacted students with behavioral problems. The teacher stated that students who exhibit disruptive behaviour may continue to do so even if the token economy strategy was used. Having experienced that the use of the token economy has impacted the students’ behaviour positively, we believe that with additional consistent positive strategies and the involvement of students in the discipline process, the positive responses towards methods used to curb behavioural problems can increase tremendously.

4) What were the Dominant Disruptive Behaviours after the Intervention?

The finding as is related to the students’ behaviour levels after the intervention showed evidence that the use of tokens in minimizing disruptive behaviour was very effective. Fewer warnings were given and more time was spent instructing students to participate in meaningful class activities. This resulted because disruptive behaviour such as frequent requests for bathroom breaks decreased to 23%, disorderly conduct decreased to 40%, fighting levels decreased to 5%, talking in the class decreased to 40%, joking in the class decreased to 10%, quarreling in the class decreased to 13% and eating in the class stopped completely.

Based on these findings it can be concluded that the use of tokens in decreasing students’ levels of disruptive behaviours has proven to be effective and can be used as a method to improve students’ behaviours as well as to motivate students. The use of the tokens also had a positive impact on the students’ academic performance, and helped in creating a more positive relationship between students and teacher and student and student. This resulted because the levels of disruptive behaviours decreased which allowed for the transformation from a tense and hostile classroom; to a classroom where students have more chances to freely express themselves and receive feedback.

Conclusion

It can be undoubtedly concluded that disruptive behaviour is undeniably a hindrance to the teaching and learning process which can be decreased by using the token economy. The students observed for the purpose of the research had behavioural problems. They displayed behaviours which were not suitable for the classroom. Researches carried out previously provide proof that the use of tokens to decrease disruptive behaviour in the classroom can be very effective. Such research provided us with the necessary guidance to implement the token economy system. From these eight weeks of intervention plan we have gained new understandings as it relates to why students behave disruptively in the class.

Recommendation

As a result of the findings of the study, the following recommendations are made:

1. A longer period of time should be given to collect quality data for future researches of this nature.

2. Change the classroom environment to a more engaging learning process to decrease disruptive behaviour.

3. Implement behavioural modification strategies at the earliest stages in the classroom for preferred and more effective outcomes.

References

- Boniecki, K., & Moore, S. (2003). Breaking the silence using a token economy to reinforce classroom participation. Teach Psychol, 30: 224-227. Chance, P. (2006). First course in applied behaviour analysis.Long Grove, IL: Waveland Publishing. Chen, C.W., & Ma, H.H. (2007). Effects of treatment on disruptive behaviour: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research using the PEM approach. Behav Anal Today, 8(4): 380-389. Darling, N. (2007). Ecological system theory: The person in the center of the circles. Res Hum Dev, 4(3-4): 231-240. Deering, C. (2011). Managing disruptive behaviour in the classroom. College Q, 14(3): 1-6. Doll, C., McLaughlin, T.F., & Barretto, A. (2013). The token economy in recent review and evaluation. Int J Basic Appl Sci, 2(1): 131-149. Elliott, J. (1988). Educational research and outsider-insider relations. Qual Stud Educ, 1(2): 155-166. Filcheck, H.A. (2003). Evaluation of a whole-class token economy to manage disruptive behaviour in preschool classroom. Department of Psychology, 1-10. Filcheck, H.A., & McNeil, C.A. (2004). The use of token economies in preschool classroom: Practical and philosophical concerns. J Early Intensive Behav Interv, 1(01): 94-103. Filcheck, H.A., McNeil, C.A., Greco, L. A. & Barnard, R.S. (2004). Using a whole-class token economy and coaching of teaching skills in a preschool classroom to manage disruptive behaviour. Psychol Sch, 4(3): 351-361. Hall, P. (2003). Building relationships with challenging children. Educ Leadership, 61(1): 60-63. Higgens, J.W, Williams, R.L. & McLaughlin, T.H. (2001). The effects of a token economy employing instructional consequences for third grade students with learning disabilities. Educ Treat Child, 24: 99. Kazdin, A.E. (1977). The token economy: A review and evaluation.New York,NY: Plenum Press. Kohn, A. (2005). Association for suspension and curriculum development. Lerner, J. (1997). Learning disabilities: Theories diagnosis and teaching strategies (7th ed.). Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin. Matalon, B. (2008). Classroom and behaviour management.Kingston, Jamaica: university of the West Indies. Matalon, B. (1998). Classroom and behaviour management. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies. Marais, P., & Meier, C. (2010). Disruptive behaviour in the foundation phase of schooling. S Afr J Educ, 30: 41-57. Merrett, F., & Wheldall, K. (1993). How do teachers learn to manage classroom behaviour? A study of teachers’ opinions about their initial training with special reference to classroom behaviour management. Educ Stud, 19: 91-106. Miller, P.M., & Drennen, W.T. (1970). Establishment of social reinforcement as an effective modifier of verbal behaviour in chronic psychiatric patients. J AbnormPsychol, 76: 392-395. Nelson, K.G. (2010). Exploration of classroom participation in the presence of a token economy. J Instruct Pschol, 37(1): 49-55. O’Leary, K.D., & Drabman, R. (1971). Token reinforcement programs in the classroom: A review. Psychol Bull, 75: 379-398. Oliver, R., Wehby, J., & Daniel, J. (2011). Teacher classroom management practice: Effects on disruptive behaviour or aggressive student behaviour. Campbell Syst Rev, 4-19. Parsons, R.D., & Kimberlee S.B. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researchers. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2002. Powell, E.T., & Stelle, S. (1996). Collecting evaluating data: Direct observation. Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with Action Research. VA: USA, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Singer, J., & Maher, M.A. (2007). Preservice teachers and technology integration: Rethink traditional roles. J Sci Teach Educ, 10(1-2): 143-154. Skinner, B.F. (1938). The behaviour of organism: An Experimental Analysis.NY: Appleton-Century. Skinner, B.F. (1966). What is experimental analysis of behaviour? J Exp Anal Behav, 9: 213-218. Tiano, J.D., Fortson, B.L., McNeil, C.B., & Humphrey, L.A. (2005). Managing classroom behaviour of head start children using response cost and token economy prcedures. JEIBI, 2(1): 28-38. Zlomke, K., & Zlomke, L. (2003). Token economy plus self-monitoring to reduce disruptive behaviours. Behav Anal Today, 4(2): 177-181.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 19375

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Dec 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 17867

- PDF downloads: 1508