A Surgically Based Two Step Dual-Prep Nasal Decolonization Method for Preventing Infection in Long-Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCA)

Received: 18-Jul-2024 / Manuscript No. JIDT-24-142198 / Editor assigned: 22-Jul-2024 / PreQC No. JIDT-24-142198 / Reviewed: 05-Aug-2024 / QC No. JIDT-24-142198 / Revised: 12-Aug-2024 / Manuscript No. JIDT-24-142198 / Published Date: 19-Aug-2024 DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000602

Abstract

In reducing hospital acquired infections and infection control for hospitalized patient’s nasal decolonization is considered as an adjunct method. This procedure involved a 90-day trial of a nasal decolonization methodology in a Long-Term Acute Care (LTAC) 40 bed inpatient hospital. Inpatients once in a day were offered a surgically proven commercially available over-the-counter two-step nasal decolonization method. throughout the study period an average 80% Patient compliance was in an average of 85% inpatient censes. A record of the number of sputum as well as blood cultures sent for microbiologic examination was observed for the positive cultures in these samples during the 3 months’ period. on patients who had physical findings and clinical symptoms of an infectious process the cultures were drawn respectively. A data of over identical chronological periods was compared between immediate pre-trial and the preceding six years.

Keywords: Nasal decolonization; Two-step; Dual prep; Healthcare Associated Infections (HAIs); Mechanical cleaning; Alcohol-based sanitization

Introduction

Nasal decolonization is now widely recognized as a vital component of infection control measures for hospitalized patients [1-3]. This study evaluated the results of a 90-day nasal decolonization trial in a forty- bed long-term acute care hospital setting. Patients were provided with a surgically validated two-step nasal decontamination procedure, administered twice daily. During this 90-day time period, the number of blood and sputum cultures sent for microbiologic assessment was noted, along with the number of positive cultures among those sent. Patients with physical or clinical signs of an infectious process had their cultures taken. The data from the nasal decolonization period was then compared to both immediate and past historical data from comparable time periods. This data was reviewed by lead authors and also outside independent contractor. The findings of this study strongly support nasal decolonization as an important factor in reducing suspected infectious processes among inpatients.

Materials and Methods

A nasal decolonization trial was conducted between 15 October, 2023 and 15 January, 2024 at a 40-bed long-term acute care hospital. All hospitalized inpatients were given the option to use a daily nasal decontamination technique during this time. The nasal decolonization method is a two-step, non-antibiotic, alcohol-based cleaning procedure that involves two different sanitizing agents in addition to mechanically washing the nasal vestibular skin. This nasal decolonization method strictly follows the two-step dual prep methodology recognized as the most effective method for surgical skin cleaning/prep at the time of surgery [4-7].

The mean inpatient census was 85% or 34 out of 40 bed occupancy during the trial period. consistently 80% of patients were found to use nasal decolonization method throughout the trial period. On prior demonstration of the two-step process by nursing staff, patients performed this technique on their own. As per the information available with the treating physician peripheral or central line samples of blood and oral or tracheostomy samples of sputum cultures were collected from the patients who had clinical evidence of an infectious process based upon their evaluation. Blood cultures were analysed regularly for fever of 38.3°C or more. Patient history and pulmonary physical exam was considered basing on the treating physician’s opinion Sputum cultures were sent for examination. Blood cultures were drawn by two techniques either from an indwelling central line if present or peripherally. throughout the period of the trial both blood and sputum, and also the number of positive cultures for bacterial growth were noted from the cultures sent. The results of the number of positive cultures obtained and the total number of cultures were considered and compared with historic data available during the period of the nasal decolonization trial. beginning from 2017 to 2023 a review of total cultures obtained and number of positive cultures for bacterial growth over the same chronologic period i.e., from 15 October, to 15 January, for the prior 6 years was considered. From the beginning 15 April, 2023, positive cultures for bacterial growth were reviewed for the 6-months period prior to initiation of the decolonization trial in 2023. prior to initiation of the nasal decolonization trial censes reports were also reviewed for all the historical time periods were evaluated. Using Z-score analytical statistics the p-value for the total number cultures obtained and the total number of positive cultures present were calculated.

Methodology

The p-value was calculated using Z-score statistics. The Z-score is a measure of how many standard deviations a data point is away from the mean. Z-scores depends on the standard normal distribution (or Gaussian) which has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

The formula used to calculate a Z score involved the observation (X), the hypothesized mean (μ), and hypothesized standard deviation (σ):

For positive cultures, the z-score of -1.9908 was calculated whereas X=10, μ=28, and σ=9.042. For total cultures, the z-score of -1.8677 was calculated whereas X=64, μ=94.375, and σ=16.263 (Supplementary Tables 1-4).

Results

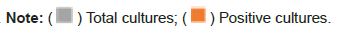

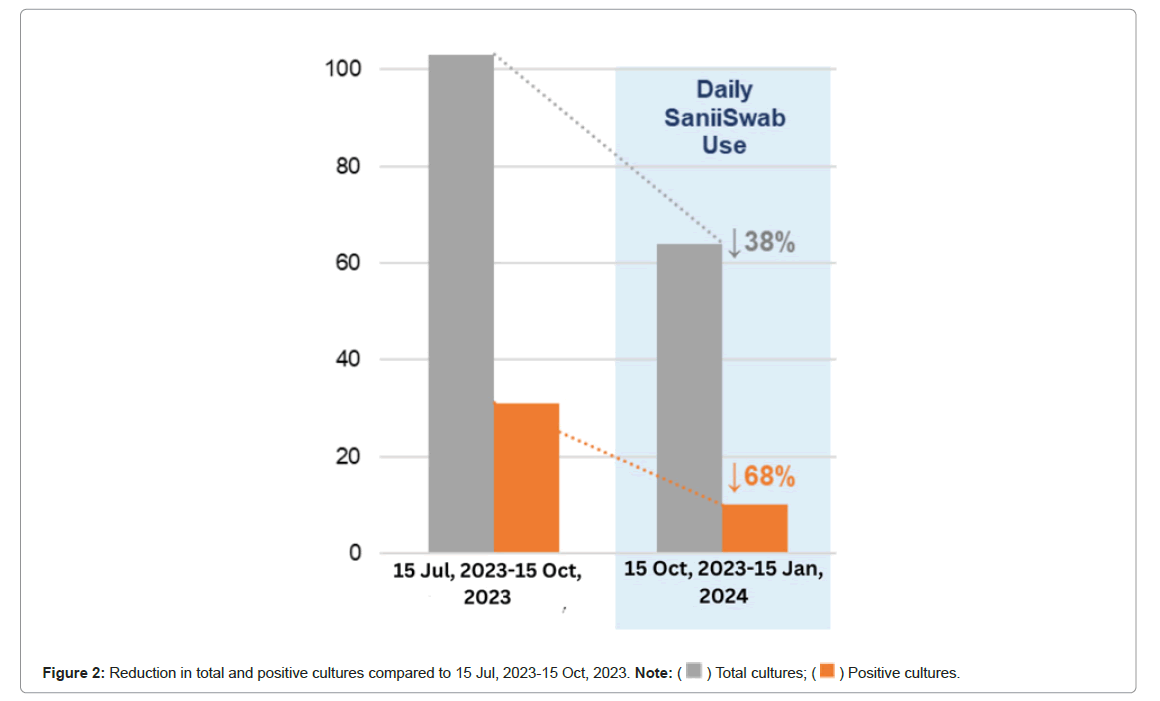

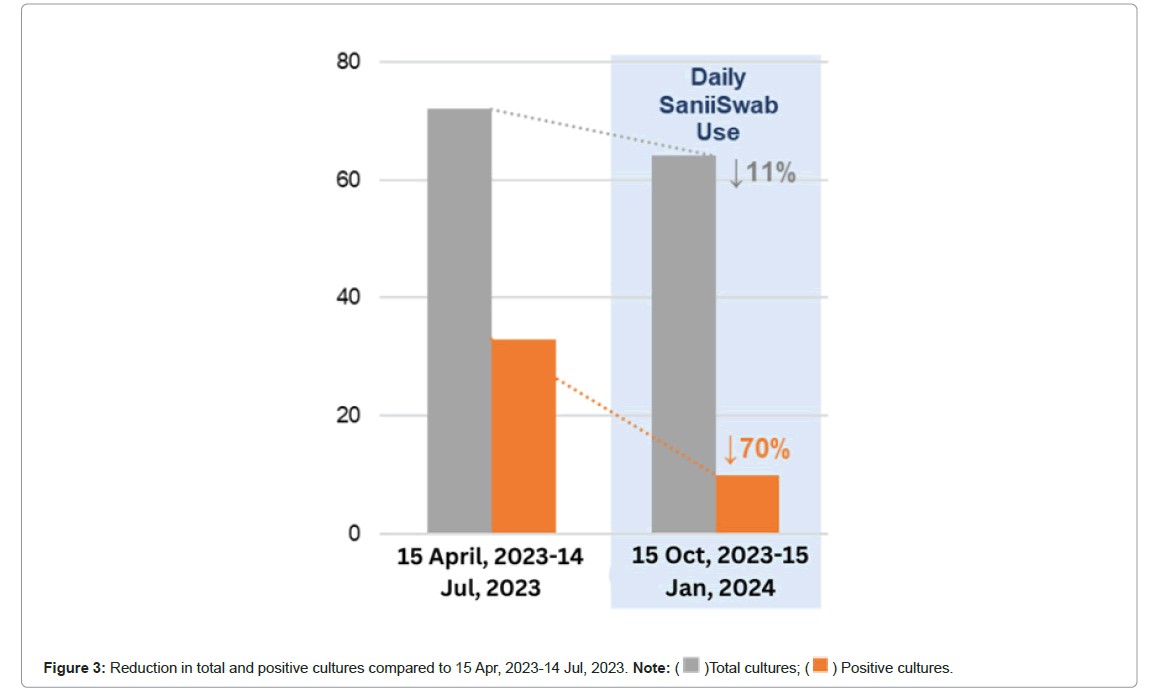

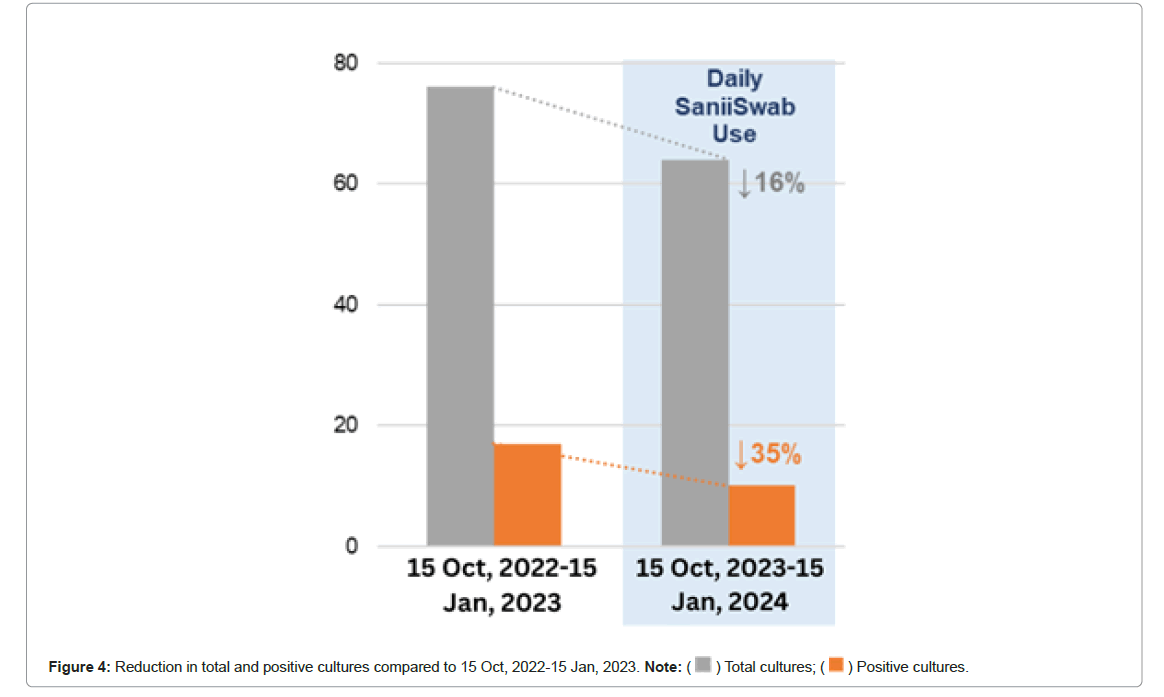

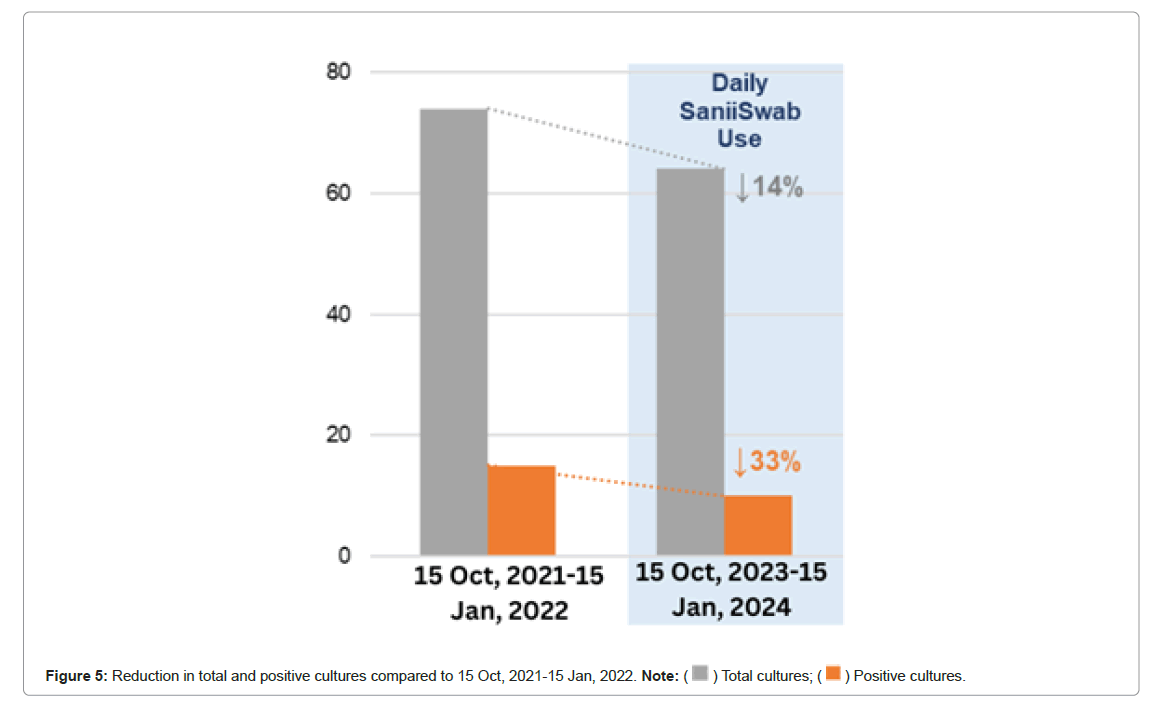

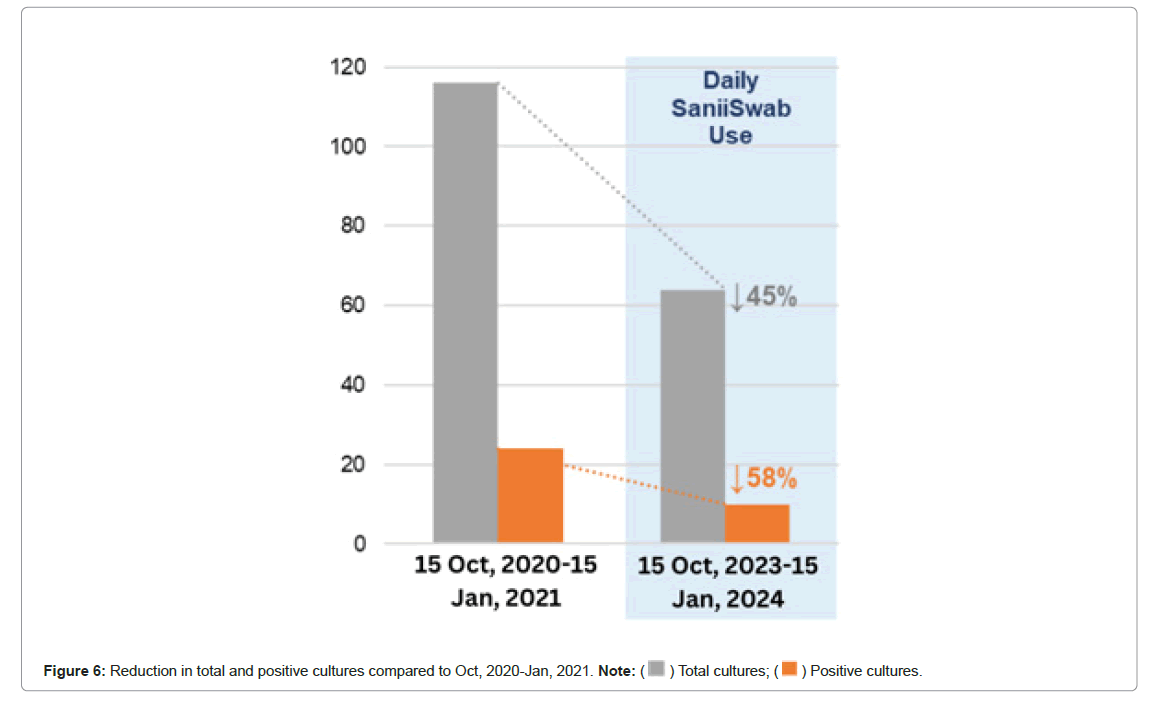

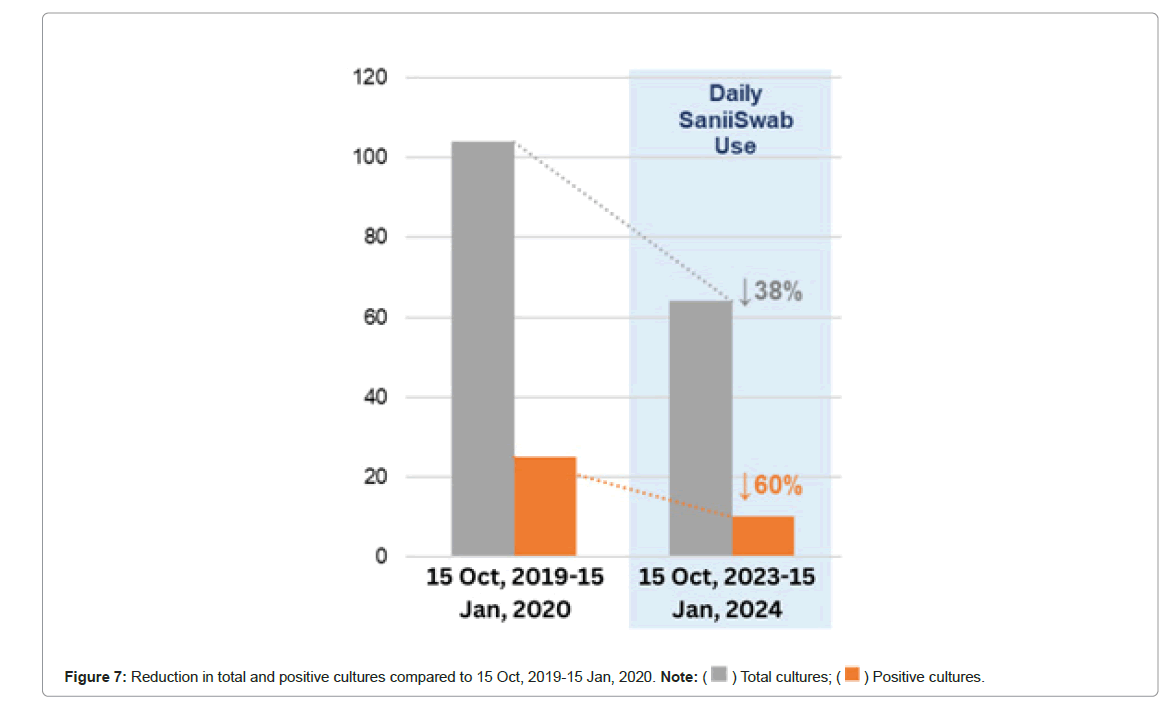

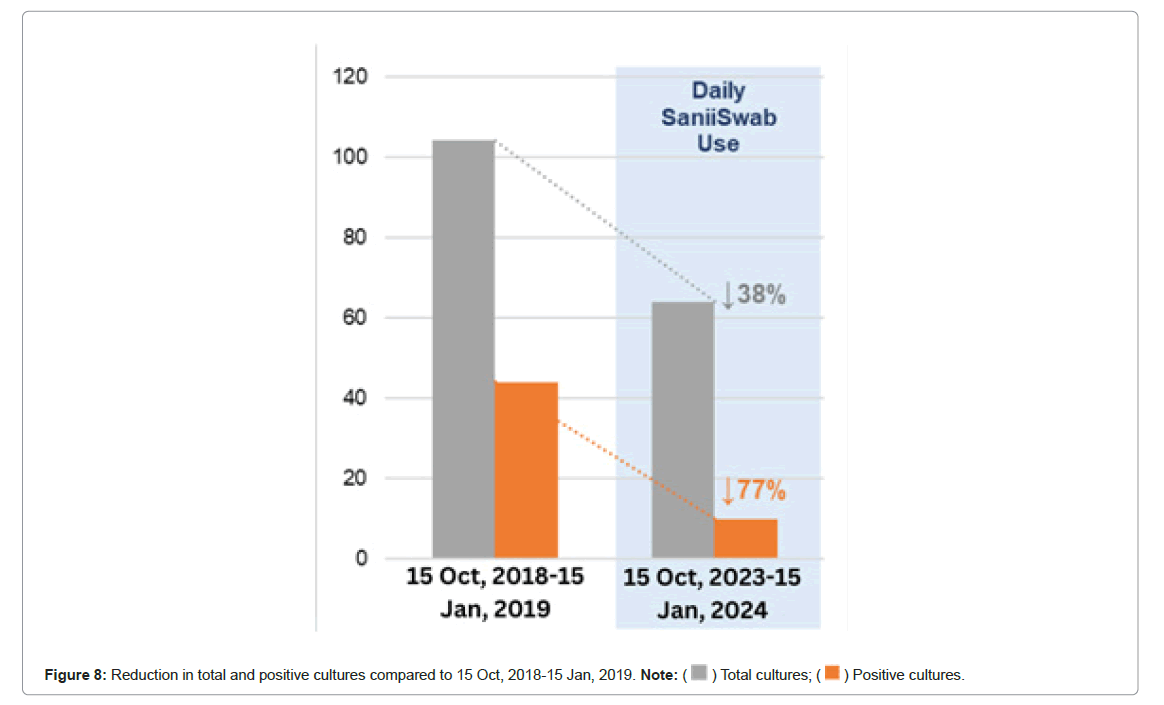

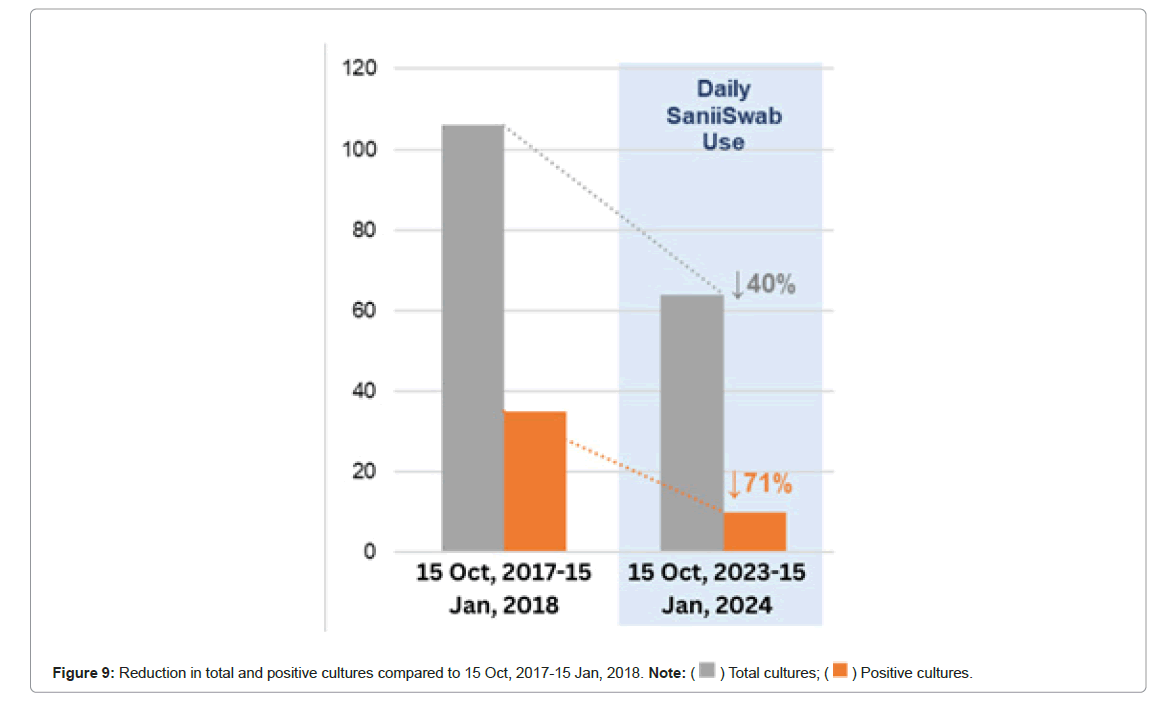

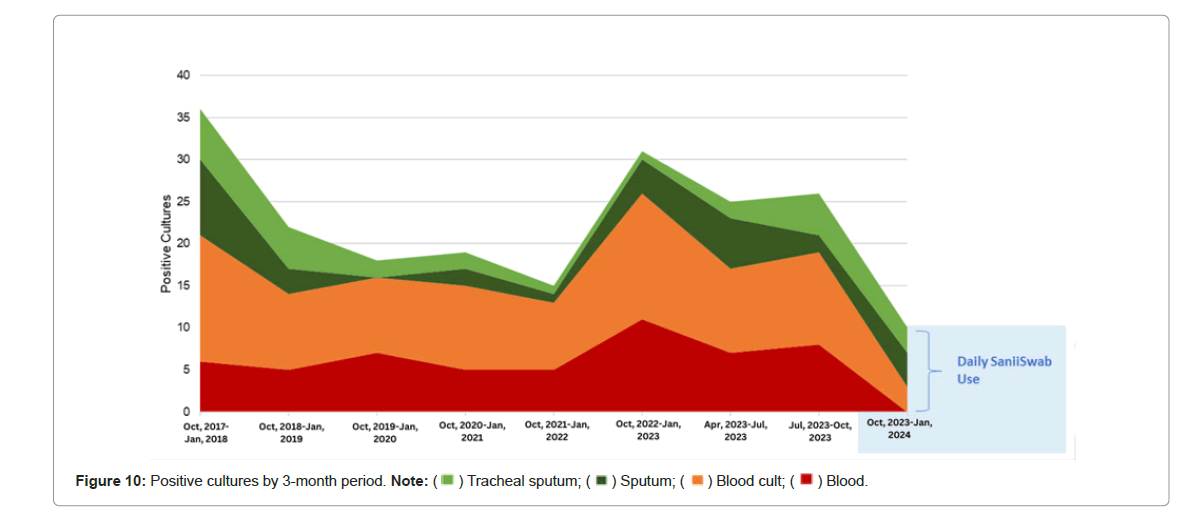

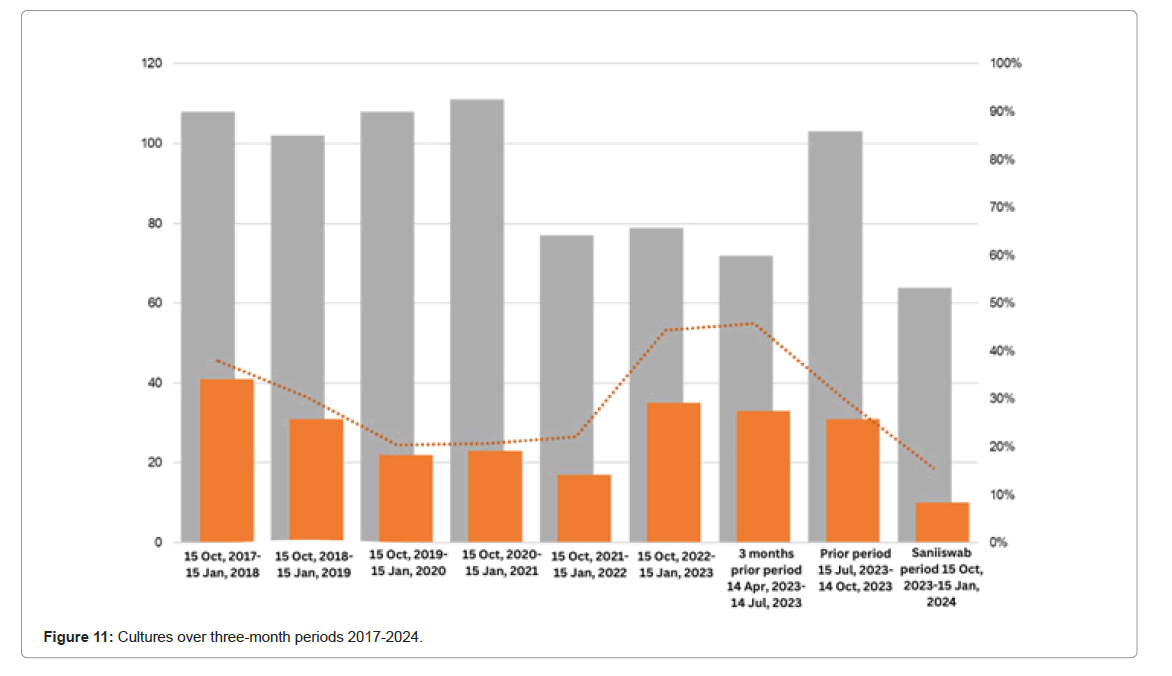

Figures 1 to 11 and Table 1 for each of the historical time periods as well as the nasal decolonization trial time period numerical and graphic results of total cultures sent and positive bacterial cultures are illustrated. An average number of total cultures sent at 97 with an average of 28% of those cultures being positive for bacterial growth, was evident from the 6-year average of the same chronologic period (Figure 1). A total of 64 cultures sent with 16% of those being positive for bacterial growth was found in the same chronologic time period, 15 October, 2023, upto 15 January, 2024 during the nasal decolonization trial. There is 63% in positive cultures and an average reduction of 34% in total cultures obtained in the nasal decolonization trial. Figures 4 to 9 elucidates the average reduction during the nasal decolonization trial of 63% in positive cultures and an average reduction of 34%. Prior to initiation of the nasal decolonization an immediate 3 months’ nasal decolonization trial was taken the number of cultures obtained during the nasal decolonization period was 68% less than that of the preceding 3 months and 38% less for positive bacterial cultures from the preceding 3 months. A reduction of 11% of total cultures was seen compared to the 3 month time period 15 April, 2023 to 15 July, 2023 and 15 October, 2023 to 15 January, 2024 a reduction of 70% positive cultures was seen. There is a remarkable relationship between the daily use of the nasal decolonization method and a decrease in positive cultures (p=.04) and a close significant relationship in the decrease of the total cultures (p=.06), the data is in Figures 10 and 11 and Table 1. The significance threshold was set at .05 (Table 1) (Figures 1-11).

| Period | Positive (count) | Total (count) | Positive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 Oct, 2017-15 Jan, 2018 | 41 | 108 | 38% |

| 15 Oct, 2018-15 Jan, 2019 | 31 | 102 | 30% |

| 15 Oct, 2019-15 Jan, 2020 | 22 | 108 | 20% |

| 15Oct, 2020-15 Jan, 2021 | 23 | 111 | 21% |

| 15 Oct, 2021-15 Jan, 2022 | 17 | 77 | 22% |

| 15 Oct, 2022-15 Jan, 2013 | 35 | 79 | 44% |

| 15 Apr, 2023-14 July, 2023 | 33 | 72 | 46% |

| 15 Jul, 2023-14 Oct, 2023 | 31 | 103 | 30% |

| 15 Oct, 2023-15 Jan, 2024 Daily decolonization use instructed | 10 | 64 | 16% |

| Average | 27 | 92 | 30% |

Table 1: Cultures over three-month periods 2017-2024.

Discussion

A HAI is defined as an infection acquired by the patient after admitting into hospital and free of any infection prior to admission. HAI’S are associated with potential high morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that 1 in 31 hospital patients develop a HAI, affecting 20 lakhs patients per an annum and accounting for over 1 lakh deaths in the U.S.A alone. The annual financial burden for treating HAI’s is estimated at over $40000 million yearly [8].

Some hospitals may feel that the cost of treating HAIs is often not covered by the patient’s insurance because the Centre for Medicare Services (CMS) penalizes hospitals with the highest rates of HAIs. Over the past 20 years, hospitals have shifted from assuming that the majority of HAIs are an unavoidable “cost of business” to believing that most HAIs are preventable, in part due to the financial incentive to reduce HAIs. Hospital programs now prioritize infection prevention over infection control. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) closely observes HAI data through state and national progress reports from individual hospitals [9,10].

HAIs are now classified into different categories, such as catheter- related infections primarily affecting the genitourinary tract, respiratory/pulmonary infections, access line infections (including those involving peripheral and central lines), and post-operative Surgical Site Infections (SSIs). It is commonly known that in cases of postoperative surgical site infections, the patient’s own endogenous sources are the primary sources of the infectious agent or bacteria. Gram-positive (+) cocci including Staphylococcus aureus are the most common organisms initially implicated in postoperative surgical site infections [8]. Like other bacteria, gram Gram-positive (+) cocci grow best in warm, moist environments with lots of water and minimal exposure to light. Additionally, like all living organisms, bacteria require nutrition for sustainability and propagation. The hair-bearing skin areas of the groin, axillae, and nasal vestibules are the best places in the human body to meet all of these needs. Warm, moist, and dark environments are three major areas protected from the outside environment, abundant in apocrine and eccrine glands that can supply bacteria with necessary nutrients, including lipids and proteins from the shedding epithelial cells of the skin. The primary goal of preoperative body washes is thorough cleaning of the axilla and groin, along with using the correct preoperative surgical preparation procedure. Cross- contamination from these body areas to other sites likely plays a significant role in the initiation of HAIs. In 1846 Ignaz Semmelweis, connected the importance of hand hygiene with infection prevention. Handwashing has recently received the most attention in assessments of HAI prevention techniques since it is essential to prevent the spread of infectious diseases in and around the hospitals [8].

It is essential to understand that infectious organisms do not, by themselves, cause infections. They only become infectious agents when they are physically transferred from the hand to an open source within the body, such as a newly formed cut or external injury a skin piercing, a catheter conduit, or an entrance to the pulmonary respiratory system. The nose is the other main hair-bearing region of the body that carries bacteria and viruses that cause infection. Today, we are finally going to recognise that nasal cleanliness is just as important, perhaps even more so, than hand hygiene in preserving good health and prevent respiratory and other HAIs. over ninety percent of the air we breathe in enters through our noses.

This air first enters the anterior nose, also known as the nasal vestibule, which is lined with skin that contains the apocrine and eccrine glands, as well as hair follicles. These fibres and viscous residues in the nasal vestibules comprise our body’s natural air filter, gathering allergens, germs, and viral infections that we inhale. Research has demonstrated that, in a clean state, nasal vestibules are highly effective in capturing particles measuring 0.5 μm or larger [11-13]. This covers all bacteria and allergen dander. Even though a single virus has a diameter of less than 0.5 μm, the majority of viruses are disseminated through aerosols that contain particles with a minimum diameter of 0.5 μm [14]. It is well known that bacteria and other microbes are significantly more heavily occupied in the anterior nose [15-18].

The aim is to suppress these bacteria early in their period of incubation before they become contagious, similar to with regularly hand washing. What is a nasal cleansing method that is safe, easy to use, and doesn’t require continuous medical supervision? The nasal decolonization methodology used in this experiment was developed based on the surgically demonstrated efficacy of a two-step, dual prep strategy for sanitising human skin before surgery.

Conclusion

Blood and/or sputum cultures were sent for patients suspected of having an infection based on a fever protocol and the treating physician’s assessment in the 40-bed long-term acute care facility where this research was conducted. Blood cultures were frequently sent based on respiratory/pulmonary physical symptoms, and blood cultures were regularly sent for patients with fevers of 101.2°F or above. The total number of cultures sent throughout the decolonization trial period was 34% fewer than the previous 6-year average, with a 20% patient noncompliance rate. Compared to the previous 6-year average, there were 63% fewer positive cultures among the total cultures sent during the decolonization trial period. Total cultures sent throughout the nasal decolonization trial period were 38% lower than those received during the three months that before the study’s start, and total positive cultures were 68% lower.

These results are not unexpected. Everyone knows how important it is to wash their hands frequently and prevent HAIs. We now have a firm understanding of the significance of decontamination and nose hygiene in preventing HAIs. The results of this study closely resemble those of a larger study by Gussin, which discovered comparable rates of infection decrease in nursing homes and long-term acute care hospitals after implementing nasal decolonization and body cleaning approaches. Nasal hygiene was practiced once day during this trial. How often do medical staff members in a hospital setting wash their hands each day, we wonder? How frequently should patients utilize the nasal hygiene/decolonization procedure is the question that needs to be answered. More research will be required to answer these queries and determine how time-effective the hygiene practices are. However, it is evident that proper nasal hygiene and disinfection, even once a day, can have a significant influence on reducing HAIs.

Evaluation of the significant financial issues is also necessary. In the United States, the average cost of treating a HAI is thought to exceed $40,000. Nevertheless, another concern is the expense of treating a HAI incorrectly if it leads to patient death.

References

- Gussin GM, McKinnell JA, Singh RD, Miller LG, Kleinman K, et al. (2024) Reducing hospitalizations and multi-drug resistant organisms via regional decolonization in hospitals and nursing homes. JAMA 331: 1544-1557.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Septimus EJ, Schweizer ML (2016) Decolonization in prevention of health care-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 29:201-22.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Septimus EJ (2019) Nasal decolonization: What antimicrobials are most effective prior to surgery? Am J Infect Control 47:A53-A57.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blonna D, Allizond V, Bellato E, Banche G, Cuffini AM, et al. (2018) Single versus double skin preparation for infection prevention in proximal humeral fracture surgery. BioMed Res Int 2018: 8509527.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, et al. (2010) Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med 362:18-26.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kallmeyer RR (2020) Fact: Progressive skin prep regimen reduces skin contamination infections. Am J Infect Control 48:515-558.

- Chen HC, Chen MC, Chen YL, Tsai TH, Pan KL, et al. (2016) Bundled preparation of skin antisepsis decreases the risk of cardiac implantable electronic device-related infection. Europace 18:858-867.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control (2021) Current HAI progress report.

- Stone PW, Glied SA, McNair PD, Matthes N, Cohen B, et al. (2010) CMS changes in reimbursement for HAI’s. Med Care 48:433-439.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen CC, Liu J, Cohen B, Larson EL, Glied S (2018) Financial incentives to reduce hospital-acquired infections under alternative payment arrangements. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 39:509-515.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oneal RM, Beil RJ, Schlesinger J (1999) Surgical anatomy of the nose. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 32:145-181.

- Patel RG (2017) Nasal anatomy and function. Facial Plast Surg 33:3-8.

- Jones N (2001) The nose and paranasal sinuses physiology and anatomy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 51:5-19.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [

- Hatch TF, Gross P (1964) Pulmonary deposition and retention of inhaled aerosols. (1st edn). Cambridge: Academic Press 1964 NY, United Sates of America.

[Crossref]

- Heikkinen T, Marttila J, Salmi AA, Ruuskanen O (2002) Nasal swab versus nasopharyngeal aspirate for isolation of respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbio 40:4337-4339.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhatta DR, Hamal D, Shrestha R, Parajuli R, Baral N, et al. (2018) Nasal and pharyngeal colonization by bacterial pathogens: A comparison study between preclinical and clinical sciences medical students. Canadian J Infec Dis 2018:7258672.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lessler J, Reich NG, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM, Nelson KE, et al. (2009) Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: A systemic review. Lancet 9:291-300.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benenson S, Cohen MJ, Schwartz C, Revva M, Moses AE, et al. (2020) Is it financially beneficial for hospitals to prevent nosocomial infections? BMC Health Serv Res 20:653.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: : Walker L, Newell L, Tong J, Polley JW (2024) A Surgically Based Two Step Dual-Prep Nasal Decolonization Method for Preventing Infection in LongTerm Acute Care Hospital (LTCA) J Infect Dis Ther 12:602. DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000602

Copyright: © 2024 Walker L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1474

- [From(publication date): 0-2024 - Nov 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1166

- PDF downloads: 308