Case Report Open Access

A New Mentorship Model: The Perceptions of Educational Futures for Native American Youth at a Rural Tribal School

Crystal Aschenbrener1*, Sherry Johnson2 and Marlene Schulz31Department Chair of Social Work, Alverno College, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States

2Director of Tribal Education with the Sisseton Wahpeton Tribe, United States

3Instructor at South Dakota State University, South Dakota, United States

- *Corresponding Author:

- Aschenbrener C

Department Chair of Social Work

Alverno College, Milwaukee

Wisconsin, United States

Tel: (414) 382-6000

E-mail: crystal.aschenbrener@alverno.edu

Received date: Jun 29, 2017; Accepted date: Jul 11, 2017; Published date: Jul 20, 2017

Citation: Aschenbrener C, Johnson S, Schulz M (2017) A New Mentorship Model: The Perceptions of Educational Futures for Native American Youth at a Rural Tribal School . J Child Adolesc Behav 5: 348. doi: 10.4172/2375-4494.1000348

Copyright: © 2017 Aschenbrener C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

A case study utilizing a mixed methods design concluded that a nontraditional-style mentorship intervention model for at-risk, Native American youth at a tribal school in South Dakota has positively impacted the youths’ perspectives of their educational futures. The mentorship intervention model was social work-rooted, theory-driven, and culturally-sensitive. The literature review discussed the lack of research for this oppressed group with mentorship programming and provided comprehension to advance mentorship program in rural reservation settings. Research knowledge of this at-risk group's social problems, historical trauma experience, and mentorship programs advanced the success of this intervention. By focusing on the strengths and needs of the tribal school, a partnership between a tribal school and two universities formed to establish a non-traditional mentorship program that positively impacted the youth and benefited the school’s strategic goals. Comparing the mixed method data of the Native American tribal rural school target youth group to a non-Native American, non-tribal, rural school youth group, findings justified the need for this intervention as well as supported the positive impact that the intervention has had on the Native American youths' educational perspectives.

Keywords

Mentorship; Tribal school; Native American

Introduction

The Today and Beyond Program: An Educationally-based Mentorship Intervention informally began in the spring of 2010 when undergraduate students from a mid-size, Midwestern university volunteered with an afterschool program at a tribal school on a reservation in South Dakota. Over the next three years the program advanced to become a theory-driven, culturally-sensitive, nontraditional mentorship program. This article will describe a research study intended to measure how this Today and Beyond Program, a mentorship program model, supported and enhanced one South Dakota tribal school’s seventh and eighth grade educational program. A goal of the tribal school is to support students’ value of high school, college, and careers while still maintaining their cultural identity [1]. However, the school struggled to find the time and resources to help students plan future educational and career goals. The non-traditional mentorship model, Today and Beyond Program, is now embedded in the tribal school’s existing programming that helps meet related strategic goals.

A case study of the Today and Beyond Program using a mixedmethods approach focused on Native American youths’ current educational norms, perceptions of educational attainment, and motivation to continue their education, as well as advancement of their cultural identity. Pre-intervention and post-intervention surveys were used to assess the outcomes of the intervention, which included a College Visit Day field trip, a Career Day field trip, and In-class Development Activities. Triangulation occurred as undergraduate students, serving as participant observers, shared observations from their field notes. To further assess the impact of the intervention, non- Native, Caucasian youth from a rural school near this targeted tribal school were surveyed. Findings from this study can be used to build a conceptual model to foster partnerships between universities and tribal school, or with other underserved minority groups.

Literature Review

Social Problems of Native American Youth

Over the years of implementing this program, the authors have discussed the many intersecting social problems that continuously diminish Native American youths’ opportunities for success in life. Well-cited social problems causing the youths to struggle to survive are not limited to severe high rates of poverty, teen pregnancy, drug and alcohol abuse, suicide, and dropping out of high school on this reservation. Additional social problems on reservation communities include child abuse and neglect; domestic violence; alcohol-related issues (drinking and driving), alcohol-related health problems (liver disease); mental health issues (depression); nutritional health issues (under and overweight); unemployment; and underemployment, as observed by the authors. This study focused on one social problem faced by Native American youths - dropping out of high school, which includes lack of college education.

Dropping-out of high school. Nationally, American Indians have the lowest high school degree attainment rates (51%) of any racial or ethnic group [2]. Native American youth in South Dakota graduation rate is more dismal at only 32 percent [2]. Tierney et al. [2] noted that national graduation rates of Native American youth have increased over the past 20 years, but graduation rates for Native youth are still lagging far behind those of non-Native students. Youth who do not complete high school often experience many long-term problems, such as the underemployment rate is higher for those without a diploma [3]. In South Dakota, the numbers are worse than the national statistics. The 20.7 percent unemployment rate for people who have not finished high school is much more significant than the 5.3 percent for those with a high school diploma or a General Education Development (GED) program completer [4].

Lack of college education. Because of the myriad of social barriers listed previously, Native American students have the lowest percentage of college enrollment and graduation rates for students aged 18 to 24 years [2]. The National Center for Education Statistics [5] found that 13.1 percent of Native Americans have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to the United States’ overall population at 28.8 percent. The lack of role models, including parents/guardians and family members, who have attended college can makes it difficult for youth to understand the process and importance of higher education [6].

History of the Social Problems: Assimilation Programs and Historical Trauma

The multifaceted social problems are often barriers associated with historical trauma caused by abusive assimilation programs, related to boarding schools, foster care system, and adoption programs - practiced just one or two generations prior. The Native children removed from their homes looked, acted, and processed information differently which negatively affected them and their future relationships with their culture, family, and reservation life [7].

With many Native children forcefully removed from their homes, Native people became fearful of social services and were distrustful of mainstream society [8]. O’Brien et al. [9] noted that these practices negatively impacted Native Americans and their education, work, homeownership, household income, and need for public assistance which stills persists today. Recognizing the impact of aforementioned problems, particularly in terms of education, is substantial. Unresolved historical trauma influences the social problems that Native American youth struggle with today.

Youth Mentorship Programs: An Intervention Opportunity

Mentors are someone to talk to, share stories with, and seek guidance from while being a resource to discuss future goals, including educational and career goals [10]. Most mentees are at-risk youth from single-parent families and/or of a minority racial or ethnic group [11].

Several mentoring models have been developed. One-on-one mentoring, such as the nationally-known Big Brothers/Big Sisters program, provides contact between a specific youth and adult. Schoolbased programs and community-based programs are similar to each other, but school-based programs provide more structure for activities and occur during school. Some programs have a specific focus on improving the academic performance of mentees. Each program provides mentors who serve as a resource and role model for the targeted youth.

Herrera, et al. [12] indicated school-based mentoring is gaining popularity and noted the strengths of the school-based mentoring are that they: 1) do not take much time of teachers and staff; 2) support children while they are at school; 3) are cost-effective; and 4) are adaptable to schools. DuBois et al. [11] found “the strongest empirical basis exists for utilizing mentoring as a preventive intervention with youth whose backgrounds include significant conditions of environment risk and disadvantage” (p. 190). Such programs contribute to academic success; however, “We did not see benefits in any of the out-of-school areas we examined, including drug and alcohol use, misconduct outside of school, relationships with parents and peers, and self-esteem” [12].

For rural communities, like South Dakota reservations, there are challenges with traditional mentorship programs. First, the sparse population contributes to a lack of volunteers who are able to serve in one-on-one mentor roles [12]. Second, often funding and resources to support mentorship programs in rural areas are scarce [13]. Finally, transportation can be a limitation [14]. Concluding that rural communities, such as reservations, are limited from such beneficial opportunities.

Then, due to the social problems and the level of oppression from historical trauma encountered by Native American youth [10,15], collaboration among programs is critical and mentorship programs should only be explored as one piece of the multi-component solution. Dondero [10] concluded that mentorship could help youth personally, educationally, and socially by inspiring hope and helping children process and experience opportunities that they may not have experienced previously. Nonetheless, research is lacking with nontraditional forms of mentorship programs as well as with Native American youth and with rural settings, including reservations.

Non-Traditional Mentorship Model

By processing the literature and considering the strengths and needs of the rural tribal school, a non-traditional mentorship intervention model was established. The mentorship model developed a collaborative partnership between the youth of a tribal school and the undergraduate students of two universities where the undergraduate students visited the tribal school over their spring semester and implemented the Today and Beyond Program. The details of the mentorship model will be further described via the case study research provided next.

A Case Study of a Mentorship Model – Using a Mixed Methods Approach

This case study assessed a non-traditional mentorship model, Today and Beyond Program, serving at-risk Native American youth from a tribal school on a reservation. This study described how undergraduate students from two partnering universities impacted Native American youths’ perceptions of their educational futures. The Strengths Perspective, the Social Learning Theory, and the Social Development Theory, with an understanding of mentorship programs within the context of the Native culture, was used to examine the youths’ perceptions.

Research Questions

Two research questions directed this research: Question #1 – In what ways does Native American youths’ perceptions about their educational futures change with the implementation of a nontraditional, educationally-based mentorship experience? Question #2 – In what ways does Native American youths’ perceptions about their educational future compare to non-Native or Caucasian youths?

Target Population

Study Group. Seventh and eighth grade students at the targeted tribal school were selected for this research program because the youth are in the final two grades at this particular school and, more importantly, they are in the two grades prior to high school (ninth through twelfth grades). On average, enrollment in seventh or eighth grades ranges from six to fourteen students. Every student in the seventh and eighth grades who were enrolled during the duration of the intervention for school year 2014-2015 and 2013-2014 was included in the study, totaling 28 youth (sixteen youth in 2014-2015; twelve youth in 2013-2014).

Comparison Group. A rural school located a few counties from the tribal school, where the students are non-Native or Caucasian, was selected for a comparison group. All except three students enrolled in the seventh and eighth grades completed the survey administrated in 2013; one student’s parent opted-out and two students were absent from school. Thirty-nine student surveys were used to evaluate how the youth who collectively not defined as at-risk or “general society” compared to the at-risk youths.

Design

This case study utilized a mixed-methods design and assessed Native American youths’ perceptions of their educational futures. The intervention was comprised of three undergraduate students from a state university in spring 2015 and then seven in spring 2014 visiting eight times over a 16-week semester. Additionally, another group of, fourteen in spring 2015 with thirteen in spring 2014, undergraduate students from a regional university who stayed at the tribal school for eleven-days at the end of the school year. The undergraduate students established a non-traditional mentorship relationship where they provided educational activities: College Visit Day field trip, a Career Day field trip, and In-class Activities and relationship development activities, such as a lock-in, service day, last day of school activities, and the end-of-the-year Pow-Wow. The Native youth had the opportunity to experience the intervention twice, once in seventh grade and then in eighth grade. Yet, most students did not participate in both years, due to not being enrolled at the tribal school both years. This study has focused on students who were in seventh and eighth grade during the 2014-2015 and 2013-2014 school years.

Research Instruments

Research instruments were developed by authors Aschenbrener and Johnson as there were no known research instruments used previously with this type of programming, for this population, and with this setting. The quasi-experimental elements of the study were included in a 32-question pre-intervention survey and a 57-question postintervention survey format with the intervention taking place inbetween the surveys. The survey instruments contained both openended and closed-ended questions that provided quantifiable responses but also enabled researchers to gain richer insights into the impacts of the mentoring model.

Data were also collected in a one-time administration to non- Native, Caucasian seventh and eighth graders from a rural school, for comparison of their expectations of their educational futures. The non-Native or Caucasian youths, from a rural school near the tribal school, completed a 24-question survey which contained questions asked to the Native American youths.

Further, triangulation of qualitative elements of the study occurred as the undergraduate students shared their observations of the Native American youths via their field notes. Two hundred fifty-one participation observation forms from the spring 2015 and 145 observation forms from spring 2014 were collected from the undergraduate students, known as informants.

Results and Discussion

This study presented a non-traditional model of an educationallybased, mentorship program for at-risk youth in a rural setting. This program is unique as it does not offer one-on-one assignments of mentors and mentees, such as with programs like Big Brothers/Big Sisters. This model focuses on a group format that allows pairing of mentors/mentees by self-selection, seeking individual mentorship, or facilitating group mentorship that allows mentees to benefit from multiple mentors of their choice. The program was also unique in that multiple visits occurred over a semester (state university) and then during an on-site eleven-day visit (regional university). This program is mutually-beneficial for both the youth and the undergraduate students. This allows the opportunity to foster a more natural mentormentee relationship that decreases trust issues which is often a barrier for at-risk Native American youth.

This non-traditional mentorship model was designed to empower the Native students to provide cultural education opportunities to the undergraduate students which positions them in the mentor role and further nurtures a healthy partnership. To help foster healthy relationships, the program is offered at the tribal school, a safe haven for the youth. Further, by having the undergraduate students reside at the school, the Native American youth feel a sense of pride and ownership of the arrangements as the undergraduate students are staying in THEIR school. Therefore, the mentorship program offers the Native American youths a unique, safe opportunity to share their strengths and concerns while learning about their educational futures.

By hosting this program at the tribal school and by preparing the undergraduate students for related cultural competency skills in advance, the program has cultural sensitivity embedded into it. By having the undergraduate students eat meals, join classes (i.e.: gym, cultural class, homeroom), and ride the school buses with the Native students, there are many informal times to establish relationships, which empowers both informal interactions as well as purposeful conversations about educational futures.

Value Interaction with Undergraduate Students

The findings strongly suggest the at-risk youth interacted more and valued their interactions more with the regional university who stayed at their school for eleven days versus the state university who visited them eight times over the semester. While, the youth had a moderate to high value of their interaction with the undergraduate students together (Table 1). Native students were asked to rate the value of their interaction on a five-point Likert scale rating (with five being the highest) during both the spring 2015 and spring 2014 of the Today and Beyond mentoring intervention. With the regional university and state university together, Cohen’s d found a large magnitude of effect for the spring 2015 intervention (Cohen’s d =0.92) and a medium magnitude of effect for 2014 intervention (Cohen’s d = 0.57).

| Year | State University N | State University Mean | State University Standard Deviation | Regional University N | Regional University Mean | Regional University Standard deviation | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 13 | 3.54 | 0.78 | 16 | 4.25 | 0.77 | 0.57 |

| 2014 | 7 | 3.71 | 1.11 | 12 | 4.25 | 0.75 | 0.92 |

Table 1: Value of Interactions with the Undergraduate Students for Two Universities; Spring 2015 and Spring 2014: Post-Mean; Post-Standard Deviation, and Cohen’s d.

Yet, the Native youths placed higher value (increase from 0.54 in 2014 to 0.71 points in 2015) on the mentors who resided at the school for eleven consecutive days, the regional university. State university students only came to the tribal school approximately every other Tuesday and were only available during the afterschool program while the regional university students stayed at the tribal school as well as interacted with the youth during informal times, such as meals, classes, and bus rides and during structure educationally-based activities which all could be used to foster positive relationships.

Healthy relationships are often difficult to build between untrusting youth and insecure undergraduate students. By the undergraduate students staying at the tribal school had value and offered a unique dynamic to the mentor-mentee relationships. Further, the data indicated that the tribal youth had to first value their relationship with undergraduate students before educational value was evident. This reinforces the fundamental social work concept that it is necessary to first establish a working relationship with the client before meaningful change can occur.

Educational Discussion

The data found that the Native youth and the undergraduate students had educational-related discussions which can be positively associated with influencing the youths’ perceptions of their educational futures, answering Research Question #1. The related survey question asked the youth to circle all that pertain to them, with such educational topics as: “my current school status,” “my plans to attend high school,” “my plans to attend college,” “ways to be successful at high school,” and “ways to be successful at college.” Even though not all the Native youth interacted with the state university’s undergraduate students mentors, they all interacted with the regional university. In 2015, twelve students (80%) identified that they interacted with the undergraduate students during one of the eight mentor visits during the school semester. Of the twelve, all (100%) indicated that they discussed at least one of the five assessed educational-related items with the undergraduate students mentors during these visits while six (50%) indicated that they discussed two items and three (25%) circled all five items. In 2015, fifteen Native American students (100%), who interacted with the student mentors from the regional university during their eleven-day stay, circled that they had discussed at least one of the educationallyrelated items with the student mentors while twelve (80%) indicated that they discussed two items and five (33.3%) circled all fiver items.

In 2014, seven students (53.9%) identified that they interacted with the undergraduate students during one of the eight mentor visits during the semester. Of the seven, all (100%) indicated that they discussed at least one of the five assessed educational-related items with the mentors during their visits while six (46.2%) indicated that they discussed two items and two (15.4%) circled all five items. In 2014, twelve of the thirteen Native American youth (92.3%), who interacted with the student mentors from the regional university during their eleven-day stay, circled that they had discussed at least one of the educational-related items with the mentors while eleven (84.6%) indicated that they discussed two items and six (46.5%) circled all five items. The data indicated that educational topics were discussed in both mentoring scenarios. However, there was greater interaction between Native youth and undergraduate mentors when mentors were embedded into the school for multiple days at one time. Concluding that these mentor-mentee interactions could be associated with positively influencing the youths’ perception of their educational future, Research Question #1.

Processing qualitative themes helped answered the Research Question #1 regarding Native youths’ perceptions about their educational futures. Many of the Native youths indicated that they enjoyed interacting with the university students. Native youths indicated that undergraduate students are “very fun to talk to;” “They were fun, happy, and respectful;” and “They’re fun and taught me a lot.” Another theme, valuing the interaction, emerged with comments such as “They [undergraduate students] really helped me and made me think more about my future;” “I liked the students and I want more than 10 days with them;” “They understand where we come from and how we live in our own ways;” and “I think that they share their high school stories. I’m just glad that they are teaching us how to say no to negative things. I would say it’s better to make healthy choices.”

The Native student responses provided evidence of Saleebey’s Strength Perspective and how this theoretical framework can be a beneficial approach with at-risk youth. Even though the social problems of poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, teen pregnancy, and high school drop-outs are concerns that are widespread on the reservation, the Strength Perspective was founded on the principle that change occurs when focusing on the individuals’ abilities and resources, not their problems. This perspective was included as part of the Today and Beyond mentoring model as it is intended to foster hope, selfdetermination, and dreams of the students, which are fundamental to the Strengths Perspective [16].

College Visit Day Motivated Youth to Continue with their Education

As the lack of parents/guardians and family members who have participated in higher education can make it difficult for youth to fully appreciate the importance of attaining a high school degree and understand the processes associated with higher education [6], the College Visit Day field trip was developed. This event exposed Native youth to the possibility of education beyond high school. By learning about college, the youth may be more motivated to continue and graduate high school. The event also provided additional opportunities for mentoring by the undergraduate students. Data were collected to assess the Native youths’ motivation to complete high school and to attend college as to determine the influence of the College Visit Day component on the Native youths’ interest in pursuing their educational futures through high school and into college. Results revealed that the College Visit Day with the Today and Beyond Program can be associated with influencing the Native American youths’ perceptions of their educational futures, which further answers Research Question #1. In 2015, sixteen of sixteen (100%) and in 2014 seven of twelve (58.3%) indicated that the College Visit Day motivated them to finish high school and/or attend college.

Qualitatively, the Native youth had the opportunity to elaborate on their perspectives of how the College Visit Day motivated them during both the 2015 and 2014, which also further answered Research Question #1. In 2015, the themes emerging from tribal youths’ responses were positive attitudes about college, event reflection, and a positive high school experience. Both negative and positive reflections were provided. Negative responses indicated the event included the “same things as last year.”

In spring 2014, the tribal youth identified college mentors’ ability to share college life stories as one theme which is evidence by the youths’ comments: “because [undergraduate students] said it’s a lot of fun” and “because they’re [undergraduate students] in college and they showed us what it’s like.” The second theme was the youths’ personal motivation as evidence by the following responses: “because I really want to go to college,” “because it would be nice to go [to college],” and “help me to a good college.” Some tribal youth indicated that the College Visit Day was not motivational in comments such as: “you didn’t get one-on-one time to visit and ask questions [about college],” “I always wanted to attend high school anyways,” and “boring.” Positive feedback indicated that the College Visit Day was an “interactive day” and “fun.” Quantitative data, supplemented by qualitative feedback from the Native youths, suggested that the College Visit Day was seen as motivational and could be associated with positively influencing the youths’ perceptions of their educational futures.

Helpful Factors to Goal Achievement

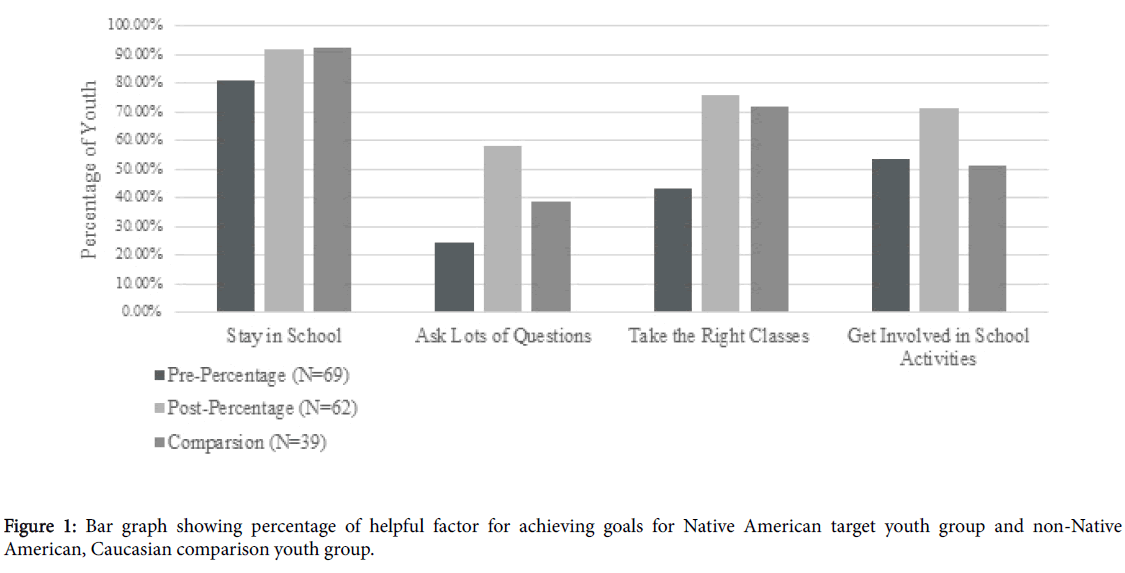

Research Question #2 examined how Native youths’ perceptions about their educational futures compared to their non-Native, Caucasian counterparts, which was addressed through the use of the surveys. Both the Native tribal school youth target group and the non- Native, Caucasian rural school comparison group were asked to identify factors helping them to achieve their educational goals via indicating a “yes” or “no” to a variety of items, such as educationallybased items: “stay in school,” “ask lots of questions,” “take the right classes that match my goals,” “and “get involved in school activities (sports, school newspaper, and others).” Additionally, the Native youth completed the same survey questions at both the pre-intervention and post-intervention stages of the Today and Beyond Program to help identify the impact of this non-traditional mentoring program while the non-Native, Caucasian group just completed their survey once with no intervention (Figure 1).

The first item, “stay in school” showed a clear understanding that “staying in school” was a good factor for a majority of the youth. Initially, over 80% of the Native students indicated “staying in school” was a positive factor before they were involved in the Today and Beyond mentorship program. After the intervention, the Native youths’ responses rose to a comparable level of the non-Native group’s after the mentoring program.

The “ask lots of questions” item showed a large change in perceptions by the Native youth. Twenty-five percent of Native youth saw this as an important factor before the Today and Beyond intervention compared to 58 percent of the Native youth identifying “asking lots of questions” as important after the intervention. Native youths’ perceptions of the importance of “asking questions” surpassed the non-Native group’s perceptions of importance (39%). Culturally valued behaviors of Native Americans are sometimes interpreted as passive in dominant society and with low-efficacy associated with historical trauma and thus any increase in such a factor could be viewed as meaningful. This data help demonstrate the impact of undergraduate student mentors’ emphasis on the value of “asking questions” to the Native youth mentees, which is repeatedly documented in the participant observations, another research instrument used with this study.

Third, “take the right classes that match my goals” was another item that demonstrated growth for the at-risk youth as well as showed a positive associated of benefiting the youths’ perceptions of their educational futures. Fourth, “get involved in school activities (sports, school newspaper, and others)” was another item. Basketball is highlyvalued as a positive activity at this tribal school. While completing this intervention, basketball was continuously discussed and played. Basketball is much more than a sport, it is an opportunity to work as a team or family, have a structured, safe, positive environment free from social problems/issues, and a place to be a kid, in a world where the kids often have adult responsibilities. While playing basketball, mentor-mentee interactions continued to stress the importance of education.

Difference in the pre-intervention and post-intervention surveys responses in the Native youths’ perceptions may be explained by applying Vygotsky’s Social Development Theory. The undergraduate student mentors served as the role models, or “More Knowledgeable Others” (MKOs). Youth mentees had the opportunity to learn about possibilities for their educational futures from interactions with MKOs via participating in the events and activities. The Today and Beyond non-traditional mentoring program demonstrates the appropriate application of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) as the data illustrated that the Today and Beyond intervention achieved its focus of being developmentally-appropriate and student-centered [17].

Projecting Ahead: When Youth are Adults

The authors’ survey instrument addressed Research Question #2 by looking at seventh and eighth grade Native youths’ perceptions in comparison to the non-Native, Caucasian youths’ perception of their future educational goals and cultural identity. The data (Table 2) indicated that there was a small to medium magnitude of effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.34) with Native youth “wanting to get additional education and/or attend college.” Further, the post-mean of the Native youth (4.30 of a 5-point scale) was higher than the non-Native, Caucasian group (4.18 of a 5-point scale). The question about “additional education” could be interpreted differently by each group. For example, both groups are rurally located in a similar area in South Dakota, yet the non-Native, Caucasian group is known as a farming community and often the profession of farmer does not require “additional education.” However, this farming community is located within 60 miles of an university known for their agriculture programs. This may have influenced this youths’ attitudes toward college attendance. It should be noted that the pre-intervention survey scores for the Native youth was high on the interest in continuing their education (3.87 out of 5) considering only 32 percent are expected to graduate [2] and the high level of other social problems and overall oppression within their tribal community. This may be an indication of the success of previous exposure to the Today and Beyond Program. All the other hand, the high mean score may also suggest that the youth are getting some level of awareness of education beyond high school, yet struggle to turn this awareness into a reality as they progress with their education into high school.

| Question | Target Pre-Mean | Target Pre-Standard Deviation | Target Post-Mean | Target Post-Standard Deviation | Target Cohen’s d | Comparison Mean | Comparison Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I want to get additional education/attend college | 3.87 | 1.43 | 4.3 | 1.06 | 0.34 | 4.18 | 1.12 |

| I want to work on a career | 3.59 | 1.28 | 4.2 | 0.94 | 0.54 | 3.95 | 0.92 |

| I want to keep up my Native American culture | 3.8 | 1.35 | 4.38 | 0.99 | 0.49 | N/A | N/A |

Table 2: When Adults, Comparing the Native American Youth Target Group and the Non-Native American, Caucasian Comparison Youth Group: Means, Standard Deviations, and Cohen’s d.

Second, the data had a medium magnitude of effect (Cohen’s d = 0.54) with the item “I want to work on a career.” Further, the postmean of the Native youth (4.20 on a 5 point scale) was higher than the non-Native, Caucasian group (3.95 on a 5 point scale). Further research could explore how the youth determined their answers to this and other series of questions. The youth consistently demonstrated variation in their responses to such series of questions; it was never a concern that the youth simply put all “5” or all “1” on a 5-point scale when asked.

Third, the data had a medium magnitude of effect (Cohen’s d = 0.49) with the item “I want to keep up my Native American culture.” This question was only asked to the Native youth as the non-Native, Caucasian group could not relate to this question. This intervention, including the undergraduate student mentors, do not teach any part of the Native American culture to the Native youth group yet the Native youths’ cultural identity increased. A possible reason for this impact, this is a mutually beneficial partnership where the undergraduate students learn about the Native American culture from the youth while the youth learn about their educational futures from the undergraduate students. Participant observation forms, a research instrument used with this study, provided numerous examples of positive interactions between the undergraduate student mentors and the youth mentees in regards to conversations about the Native American culture, such as an elementary discussion on how to dress for a sweat lodge ceremony or in-depth conversation on what being “Dakota” means to the youth. The post-intervention surveys’ written comments noted how the youth want to be like the undergraduate students and continue on with their education just like the undergraduate students’ final comprehensive papers are filled with positive reflection on their cultural awareness that they gained from the youth.

Bandara’s Social Learning Theory was used to support this intervention (treatment) on how the Native American youths learned from interactions with undergraduate student mentors, the role models, as practiced by Bandura [18]. Further, Social Learning Theory’s concept of self-efficacy was embedded in this intervention. The undergraduate students and the educational events and activities reinforced the value of continuing education for the youths, which was intended to empower self-awareness and motivation for the youths. Accordingly, building the youths’ confidence could increase their selfefficacy which could motivate the youth to learn and process how to achieve their goals. By increasing the youths’ self-efficacy through interactions with undergraduate students who role model positive behaviors and teach related knowledge and awareness could possibly motivate the youth to navigate the challenging social problems in their lives as they focus on their achievement goals [19].

Implication

The study results concluded that the Today and Beyond Program has impacted the youths’ perceptions, particularly of their educational futures. The study’s findings can help social workers identify the value of mentorship programs and how they can be adapted to at-risk groups, such as Native American youth and to rural setting, such as reservations. This program noted that many supports are needed to fully address the intersecting, overwhelming social problems that the at-risk Native American youth struggle with daily. Thus, the skills of networking and building collaborative partnerships were practiced, common social work skills.

Social work best practices of cultural competency was incorporated and applied throughout the Today and Beyond Program. For the undergraduate students to best serve as mentors, they first needed to understand the hardships associated with historical trauma as well as the supportive strengths of the Native American culture, tradition, and spirituality. Further, with poverty, often youth live moment to moment and struggle to dream about their futures and thus, the undergraduate students needed to prepare accordingly.

Programs like this intervention model can help the Native American youth grow educationally while serving as a key function to foster social change for Native American youth, their families, and their communities. This partnership between a tribal school and two universities has provided motivation for the youth who need to further foster personal growth and change the social norms of their environment that negatively affect educational achievement while helping them establish a new way of life for themselves and future generations [20-22].

Conclusion

Today’s mentorship programs are expected to provide more services, more benefits, and more outcomes than previously practiced programs, which this mentorship model did. This study demonstrated that this intervention directly focused on the social problem of dropping out of high school by focusing on impacting the youths’ perceptions of their educational futures. The study contributed to the knowledge base of social work practice as well as Native American youth, rural areas, and non-traditional-style mentorship models, all underrepresented populations in research.

Via the mixed methods approach, the at-risk Native youth indicated that they valued their interactions with the undergraduate students as well as the data provided evidence of educationally-based discussions and experiences occurring. The College Visit Day (one of the main components of the intervention) motivated the Native youth to continue with their education. Such findings can be associated with positively impacting the youths’ perceptions of their educational futures and answering Research Question #1.

With Research Question #2, the data concluded the Native youth did identify helpful factors to achieving their educational goals and when compared to the non-Native, Caucasian youth, it showed association of making a positive impact on the Native youth. Then, when comparing the educational goals data of the Native youth to the non-Native, Caucasian youth, the intervention could be associated as making a positive impact as well.

References

- Enemy Swim Day School (2016) About ESDS.

- Tierney WG, Sallee MW, Venegas KM (2007) Access and financial aid: How American-Indian students pay for college. J College Admission, Fall 197: 15-34.

- Edwards KA (2009) Minorities, less-educated workers see staggering rates of underemployment. Economic Policy Institute.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2009) Appendix 1: Unemployment rates by level of education-by state.

- National Center for Education Statistics (2008) Table 7.1. Percentage distribution of adults ages 25 and over, by highest level of educational attainment and race/ethnicity: 2007. Status and trends in the education of American Indians and Alaska Natives: 2008.

- Tyler JH, Lofstrom M (2009) Finishing high school: Alternative pathways and dropout recovery. Future Child 19: 77-103.

- Adams DW (1995) Education for extinction: American Indians and the boarding school experience, 1875-1928. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS.

- Mooradian JK, Cross SL, Stutzky GR (2006) Across generations: Culture, history, and policy in the social ecology of American Indian grandparents parenting their grandchildren. J Fam Social Work 10: 81-101.

- O’Brien K, Pecora PJ, Echohawk LA, Evans-Campbell T, Palmanteer-Holder N, (2010) Educational and employment achievements of American Indian/Alaska Native alumni of foster care. Fam Soc: J Contemp Social Services 91: 149-157.

- Dondero GM (1997) Mentors: Beacons of hope. Adolescence 32: 881-886.

- DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, Cooper H (2002) Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol 30: 157-197.

- Herrera C, Baldwin Grossman J, Kauh TJ, Feldman AF, McMaken J (2007) Making a difference in schools, the Big Brothers Big Sisters school-based mentoring impact study. A Publication of Public/Private Ventures, 1-8.

- Brescia W (1991) Funding and resources for American Indian and Alaska Native education. Indian Nations at Risk: Solutions for the 1990s. Department of Education, Washington, DC.

- Whitefoot PK (2010) Testimony before the House Subcommittee on Interior Appropriations March 23, 2010.

- Rhodes JE, Bogat GA, Roffman J, Edelman P, Galasso L (2002) Youth mentoring in perspective: Introduction to the special issue. Am J Community Psychol 30: 149-155.

- University of Kansas (2013) What is the strengths perspective?

- Levykh MG (2008) The affective establishment and maintenance of Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. Educational Theory 58: 83-101.

- Bandura A (1969) Principles of behavior modification. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc, New York, NY.

- Cross SL, Day AG, Byers LG (2010) American Indian grand families: A qualitative study conducted with grandmothers and grandfathers who provide sole care for their grandchildren. J Cross-Cultural Gerontology 25: 371-383.

- Earle KA, Cross A (2001) Child abuse and neglect among American Indian/Alaska Native children: An analysis of existing data. Casey Family Programs, Seattle, WA.

- Harris E, Malone H, Sunnanon T (2011) Out-of-school time programs in rural areas. Harvard Family Research Project, Research Updates, 6, 1-5.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2012) American Indian and Alaska Native heritage month. CB12-FF.22, October 25, 2012. U.S. Census Bureau News, Profile America Facts for Features.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3322

- [From(publication date):

August-2017 - Apr 06, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 2516

- PDF downloads : 806