Research Article Open Access

A Grounded Theory Exploring the Health Status Perceptions Shift of Women Living with Breast Cancer

Hébert Maude1*, Gallagher Frances2 and St-Cyr Tribble Denise21University of Quebec in Trois-Rivieres, 3351 Boul. des Forges. C.P. 500, Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, G9A 5H7, Canada

2Nursing School, University of Sherbrooke, 3001, 12e Avenue Nord, Sherbrooke, Quebec, J1H 5N4, Canada

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hebert Maude

University of Quebec in Trois-Rivieres, 3351 Boul. des Forges. C.P. 500

Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, G9A 5H7, Canada

Tel: 819-376-5011

E-mail: Maude.Hebert@uqtr.ca

Received date: May 28, 2016; Accepted date: June 16, 2016; Published date: June 30, 2016

Citation: Maude H, Frances G, Dennis SCT (2016) A Grounded Theory Exploring the Health Status Perceptions Shift of Women Living with Breast Cancer. Breast Can Curr Res 1:109. doi:10.4172/2572-4118.1000109

Copyright: © 2016 Maude H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Breast Cancer: Current Research

Abstract

Being diagnosed with breast cancer is a significant change in the health status of a person causing an internal process, a transition between health perceptions and disease reflects a social process. The methodology of grounded theory highlights the process. The purpose of this study is to propose a model of the transition from perceptions of women's health diagnosed with this cancer. 32 women at various times in the course of the disease have been encountered during semi-structured individual interviews. The results show that perceptions of health status are modulated throughout the course of the disease. Health becomes more valuable and cancer becomes surmountable. Women are redefining their health by not declaring patients with breast cancer and learning to live with a sword of Damocles over the head.

Keywords

Breast cancer; Transition; Perceptions of health and disease

Introduction

Each year, nearly 1.38 million women worldwide learn they have breast cancer diagnosed. This number makes breast cancer the most prevalent in women, and this, as in Western countries than in developing countries [1]. The most recent statistics estimate that 24,400 Canadian women were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, representing 64 women every day [2]. Over 88% of women with the disease have a life expectancy of five years or more that now ranks among the cancer chronic diseases [1]. Its impact on family, community and society are disastrous on women social roles since cancer has an impact on energy level, body image and sexuality [3-8], but especially because of the association of breast cancer with death and random statistics about healing [9,10]. Women must go through a transition between the perceptions they had of health and cancer before receiving the diagnosis and these perceptions after such a menacing diagnosis while fighting for their lives. Therefore, it is important to explore this perception shift to better understand how women see their illness to eventually offer them care that suits them.

Literature Review

Different approaches to the transition are proposed in the literature. The most popular in nursing is certainly the theory of transition Meleis [11,12]. This concept is often described as an "intermediate and internal process of change caused by events out of control between two relatively stable periods that last for a while" [13-15]. Some studies have focused on the transition between health and disease [6,16-20], however without comparing changing perceptions of health status before and after diagnosis.

We also noted that women's studies of breast cancer are performed at four main points during the course of chronic disease: 1) the waiting period before receiving the official diagnosis [21-23] 2) the period of shock following the diagnosis [3,24,25] and the interventions [26-28] 3) the chronicity and the adaptation [29,30], and finally 4) the recurrence and palliative care [31-33]. By cons, little attention is paid to the perceptions of health status [34-36]. Indeed, perceptions of women to health and disease remain poorly explored by nurses [37]. Also, the studies dealing with cancer perceptions examined the risk perceptions of suffering and the causes of this disease [38] do not offer a holistic view of perceptions health status.

The literature review allows us to better understand how women live between being healthy and being diagnosed with a serious illness such as breast cancer. Moreover, the evaluation of these perceptions is important because they determine the level of psychological distress, coping strategies and adherence to the proposed treatment [11,39,40]. Furthermore, we noticed that a common a priori to studies on illness perceptions was to consider women interviewed as sick as they carry the breast cancer label. This makes it possible to explain the fact that these studies have explored the perceptions of the diagnosis rather than its evolution between before and after breast cancer. Research exploring the process of transition between perceptions of health status is necessary to understand the step change between being healthy and being diagnosed of a serious and chronic disease since to date this subject remains little explored.

Methods

Grounded theory then appeared as the methodology of choice since it allows deeply understanding and elucidating social processes, while developing a theory based empirically, and, from the point of view of the actors. Women with breast cancer are actresses who interact with reality by giving it a meaning and it is possible to identify that meaning by accessing as possible to their symbolic universe [41]. Especially in oncology, it appears that breast cancer perceptions access to this symbolic universe strongly influenced by the person himself interacting with his family, friends, health care professionals, insurance companies, etc. [10,31,42]. Also, actions and their choice of treatment are based from the meaning they attach to them. For example, a woman who sees her illness as serious will be more inclined to accept chemotherapy treatments that a woman who does not perceive as being sick [10].

Sample

This study comprises three care settings where women with breast cancer were recruited: 1) A university, 2) A hospital that provides tertiary care in Quebec, Canada, and 3) Specialized hospital in the same region.

Selection and description of participants: Using the MTE, we used a theoretical sampling which allowed participants to choose according to their relevance to the development of conceptual categories and their relationships rather than population representation purposes [41]. Specifically, theoretical sampling aims to select women that maximize opportunities to compare the events and deepen the categories on the topic [43]. The starting convenience sample is determined by the research question. Thereafter, it is continually revised in response to analyses and becomes a theoretical sampling. For example, women belonging to the departure of the convenience sample should present the following criteria: 1) be aged between 40 and 60 years, 2) have commenced or completed chemotherapy, radiotherapy or have had surgery for breast cancer, 3) have no personal history of cancer, 4) not be with aphasia or debilitating psychological disorders, 5) speak French and 6) desire to participate in the study. As and progresses interviews and analysis with concomitant constant comparison of the collected data and literature, we have diversified the range of women's and meet the inductive hypotheses that generated analysis.

Breast cancer mainly affects women between 50 and 69 years. According to the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation [44], even though it affects 52% of women in this age, the fact remains that the number of younger women with the disease is significant, 18% under 50 years. According to the same source, women under 50 years are not systematically covered by the breast cancer screening program, despite that women at risk of developing the being [45]. In this study, the investigator chose to target women between 40 and 60 years, representing a prevalence of just over 39% since this age group is included in several scientific research [46-48] and the breast cancer perceptions are influenced, among others, by age [49]. Therefore, these authors argue that younger women live cancer harder than those aged over 70 years. Thus, the investigator wanted to highlight these elements of the experience of the women interviewed to develop a theory incorporating a wider variety of experiences.

Thus, we interviewed women at different times of chronic illness trajectory is: newly diagnosed women with cancer; having lived up to three recurrences; who underwent lumpectomy or total removal of the breast in addition to chemotherapy and radiotherapy; having been diagnosed with stage 0 as well as women in palliative care. Always to vary the theoretical sample and get extreme cases, interviews were conducted with a healthy woman non-carrier of BRCA1 abnormalities (Breast Cancer gene) and with a woman who was carrying BRCA1 abnormalities. With a diverse sample, the data collected promote understanding and theorization of the phenomenon under study [43].

We met once women are at various stages of the trajectory of the disease rather than opting for a longitudinal study. It would have been unrealistic in terms of feasibility, to interview women from the diagnosis and follow up palliative care since the duration of the cancer trajectory from a few weeks to several years. By doing so, it was possible to explore the transition perceptions of health in various settings of the trajectory of the disease. Moreover, by the principle of diversification, we wanted to offer an overall picture of the transition from perceptions of women's health with breast cancer over the transition own vision at a specific time of the trajectory of the disease. Each interview, at a specific time of the illness trajectory, gives a portrait of the experience. Thus, taken together, these stories are planning a different overall picture of each of them individually [50].

Data collection

Following the approval of the research project by the ethics committees and scientist at the University of attachment and the two participating hospitals, 32 women were recruited. The women interviewed were encountered in a place of their choice (home, office the first author located at the university or coffee). First, at these meetings, the first author read the information and consent form with participating, then answering questions where appropriate. Secondly, women filled the demographic questionnaire and thirdly, the semistructured interview type unfolded. Each participant was encountered for a single interview, recorded in digital audio version of an approximate duration of 60 to 90 minutes. It was impossible to predict with accuracy the number of interviews to be conducted since it depended on the theoretical saturation, that is to say, until no new data emerges to refine the theory of the phenomenon.

Semi-structured interviews: According to Denzin et al. [51], a researcher may use qualitative maintenance to 1) explore in depth the perspective of actors, 2) know, interior, social issues and 3) illuminate social realities. Since these three reasons are reasons of this study, it is obvious to use the qualitative interview to access the experience of women with breast cancer.

It is important to emphasize that the principles underlying the art of allowing others to speak [51] were met during interviews. All of the women interviewed phoned the student to voluntarily participate in the study, which demonstrated their interest in participating in this research. When the first author insisted on freedom of participation while reading the information and consent form, all the women stressed that they were eager to share their experience to advance science and help future women with cancer breast. They were convinced of the usefulness of research. To gain the confidence of the interviewed, the first author made sure to mention, by reading the information and consent form, the use made of the data collected. No woman has indicated, during the interview she feared negative consequences arising from their participation in this research. Despite its consent to participate in the study, only one woman was unable to do because of his death from this disease.

To put the interviewee at ease, the participant chose the time and place of the interview. As for the student, she showed listening, empathy and interest in participating in using communication techniques such as silence, reflection, empathy, probing questions [52]. Her experience as a nurse clinician in oncology has contributed greatly to women's confidence and decreased language barriers assigned to the medical jargon. Encouraging the interviewee to take the lead of the story and commit was easy since the participant was invited to speak about her experience since she was diagnosed; making a lot of sense to her. It was clear to the first author that every woman had a true discourse since trade was natural and spontaneous.

Memos: Written sporadically, when an idea emerged from the minds of the team members, and all throughout the research process, they serve to document the evolution of the theory [41,43]. To facilitate the linking of categories or concepts and mapping, the writings of the authors on the theory rooted corroborate the importance of write memos [41,43]. Here is a sample memo written and coded following an interview: "I have observed that women seem to live as the cancer bereavement. They go through the same steps? Are certain categories should be combined? ".

Data analysis

In Grounded theory, three techniques facilitate data analysis: 1) coding, 2) the constant comparison of data and 3) schematizations. Data analysis was conducted in conjunction with the data collection and simultaneously with the constant comparison of data between them and with the literature, always to respect the principle of circularity of grounded theory [41,43]. This is illustrated by the many aller-retour between the data collected during the interviews, coding memos, analysis and scientific writing. Also, team discussions generated new ideas or assumptions that changed the interview guide in order to support the developing theory [43]. It is important to emphasize that emerging categories were used to develop a new analytical framework rather than be placed in an existing grid derived from a theoretical model or a literature. This is due to the fact that the questions were designed to discover new ideas rather than support a theory. Here are some examples of questions that have been modulated and were adjusted to suit each woman interviewed to better understand the phenomenon.

1. What are the steps you've crossed to come to see health and disease, as you see today?

2. In your experience, are there times when you are perceived as being ill? If not, under what circumstances would you have perceived yourself sick?

Also, to increase the participation of women and, by extension, the credibility of the results, we asked the opinion of the women interviewed on the analysis of results achieved once the interview is over [43].

One of the steps of the data analysis is done through coding, which consists of three levels, namely open coding, axial and selective, which we will detail below. In this study, we relied on the steps of Strauss and Corbin [43], since these authors offer a detailed guide for analysis and they are within the same paradigm as the authors.

Open coding

This first step of encoding used to name the important concepts that emerge from the analysis of the interviews. The code is used to put a word or a "label", as illustrated Paille [53] on the main idea that summarizes a sentence or paragraph. Essentially, the researchers questioned the data by questioning as follows: What are we talking here? In front of what phenomenon am I involved? [41,43]. Categories such as "reactions following the diagnosis", "health perceptions," "perceptions of the disease" and "transition" are examples of this first encoding step. Then these codes were grouped according to their properties (characteristics that define concepts) and size (variations properties that specify the extent of the concepts), thereby raising the conceptual level and form categories [41]. In addition, comparisons between the codes and categories were continually made to use the right word to identify the code and also group similar codes or create new ones. For example, one of the properties of the category 'perceptions before transition' is' perceptions of health "while the dimension associated with this category is the" sense of invincibility "that varied between 1) the not to think about the disease and 2) the magical thinking that cancer affects everyone else except themselves. Writing memos concurrent to the development of the open coding grid has been invaluable to the development of theoretical conceptualization.

Axial coding

This second stage of coding, axial coding, the relationship is in step classes and serves to make connections between different concepts named at the open coding and raising the level of analysis at a conceptual level that encompasses said phenomena [53]. The researchers then asked the corpus such as: Are these concepts are related? What and how are these concepts? What effect resulting?

It may also happen that some codes appear opposite one another. At first glance, this dichotomy in discourse may seem contradictory when in fact it pushes researchers to differentiate, nuance and clarify the phenomenon of interest. So do not ignore them.

The mapping of the transition from perceptions of the health of women with breast cancer proves an essential step since it makes the dynamic data in the explanation of the phenomenon under study, which may take multiple tangents [53]. Besides, Strauss and Corbin [43] recommend to do a sketch at the end of each interview to identify relationships between concepts.

Selective coding

This third stage of the coding used to delineate the results of the study that take shape and thus integrate them into different categories. The analysis in the Grounded Theory can lead the researchers in unexpected directions at the beginning of the research. Therefore one must ask: "What is the specific topic of research?" The researchers identified the theoretical core also called central category of the study can be compared to a movie title [43]. The identification of this major category to reduce the number of codes and categories to develop the theory and, by extension, refines, adjust and review the links between concepts [43]. It should be noted that these steps of analysis of the Grounded Theory does not occur unidirectional, but that return are quite normal and even desirable in this helical research process [54].

Results

Socio-demographic profile of the participants

An expanded description of the context in which the study took place enables data transferability. Thus, we will endeavour to describe the best possible participants and their environment. So we found that all pf the women were Caucasians, half of them were aged between 51 and 55 years and three-quarters had a university education, and lived with a partner. They all had had surgery, a lumpectomy, a removal of the breasts, and the vast majority of them had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy (Table 1).

| Participants’ Characteristics n=32 | |

| Age (years) | n |

| 40-45 | 5 |

| 46-50 | 4 |

| 51-55 | 14 |

| 56-60 | 9 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 3 |

| Spouse | 25 |

| Age at the time of the diagnosis (years) | |

| <30 | 1 |

| 30-39 | 3 |

| 40-49 | 14 |

| 50-59 | 13 |

| 60 | 1 |

| Healthy, not carrier of the gene | 1 |

| In palliative care | 2 |

| Recurrence | 5 |

| Carriers of the gene putting them at risk of developing breast cancer BRCA1 or BRCA2 | 3 |

| Contact with persons with cancer | 32 |

| Familyincome (Can $) | |

| <10,000 | 2 |

| 10,000-29,000 | 2 |

| 30,000-49,000 | 12 |

| 50,000-79,000 | 2 |

| >80,000 | 12 |

| Refused to say | 2 |

| Schooling (years) | |

| <6 | 0 |

| 10-Jun | 5 |

| 13-Nov | 2 |

| 14 | 14 |

| 15 or more | 11 |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 32 |

| Chemotherapy | 21 |

| Radiation | 25 |

| Curitherapy | 3 |

| Breast reconstruction | 4 |

| Alternative medecine | 1 |

Table 1: Participants’ characteristics.

Transition perceptions of women's health diagnosed with breast cancer

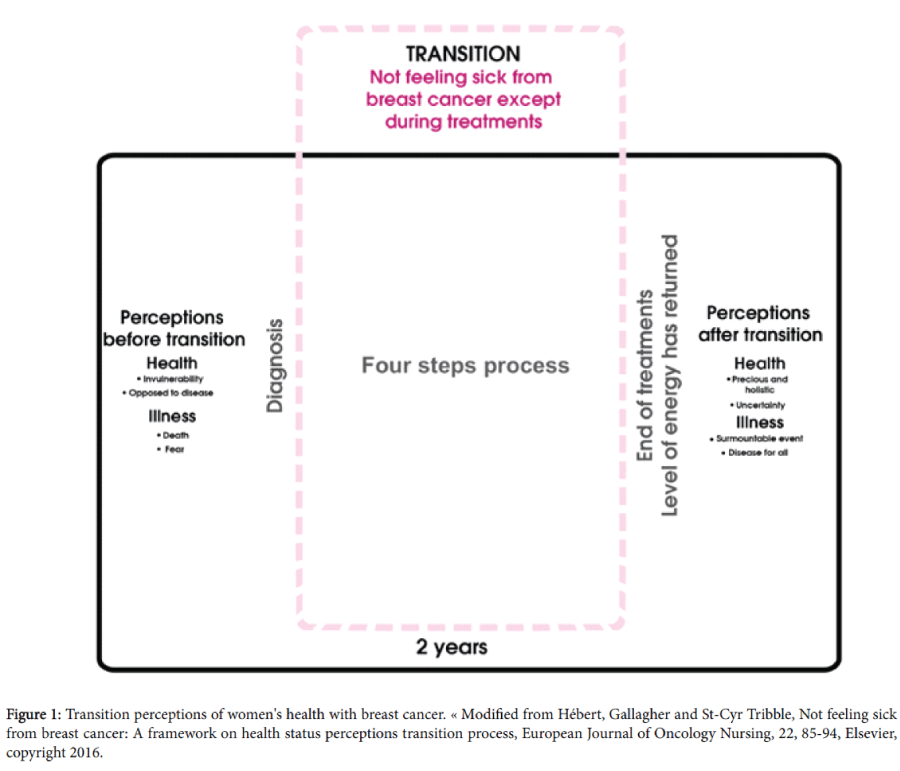

Three categories emerged from the analysis: 1) perceptions of health and cancer before the transition, 2) perceptions of health and cancer after the transition, and 3) the transition stages perceptions of health status crossed by women. In this article, the results of the first two categories will be presented while those on the steps of the transition perceptions of health are the subject of another publication [55]. The following Figure 1 incorporates the emerging categories of analysis and facilitates the understanding of the health status perceptions shift of women living with breast cancer.

Perceptions of health and breast cancer before diagnosis health perceptions: Data analysis identified two major categories of health perceptions before the transition: 1) Invulnerability and 2) Opposition to the disease.

"Invulnerable" is how women saw themselves before the diagnosis of breast cancer, as illustrated that participating in these terms: "It was not for me. It was to everyone around me and I would never have that. It will not reach me". Healthy women do not linger to cancer and believe themselves protected by their heredity: "I felt that there were many familial histories that caused cancer and I could not have it because 'there is not even in my family".

Women interviewed did not think of the disease as they felt no systemic symptoms in most cases as mentioned in this excerpt: "Breast cancer, it does not hurt. That's what is terrible because you are diagnosed with cancer and you do not feel it. I was healthy. I was never sick and I was diagnosed with something strong". Moreover, they were taken into the daily routine which takes place at lightning speed. Health is linked to the energy capital in addition to being acquired and to enable the tasks of daily life. Thus, a participant illustrates this: "I think health is something we often unknowingly. Something that we forget we have". In addition, the participants particularly stressed the dichotomous aspect of health and disease: "They are two opposites like sweet and salty. You do not know until you do not have tasted". In short, perceptions of health when participants are healthy appear unconscious rather naive.

Perceptions of breast cancer

Three major subcategories have emerged from the category 'perceptions of cancer ": 1) death, 2) fear and 3) doubt whether heredity.

"Before the diagnosis, I would say that the cancer was really meaningful to death". "It was as if there was no way out. It was the end". This is the image that came to mind when women heard the word "cancer" before developing it. The cancer was directly associated with death. The cancer perceptions caused a great fear of death and change of body image in healthy women when they heard the word "cancer" as mentioned in the following women: "I had already told me that the worst case it could happen to me was breast cancer". "Thinking about losing a breast, was terrible". Some women also experience fear toward treatments that are sometimes seen as "poison that enters your body to kill the monster. It takes poison to kill a poison".

We also note that women whose family members have been affected by breast cancer, feelings of psychological distress. For example, one participant explained his reaction: "A couple of months after the death of my mother, I panicked. I had brought information of the Quebec cancer centre. It was panic". The sense of invulnerability falls and women realize they could, too, develop cancer as evidenced by the following extract: "I knew I was playing with [the risk of breast cancer]".

Perceptions of health and breast cancer after diagnosis: We note that perceptions of health and cancer have changed as a result of the experience of living with such a serious illness. Indeed, health is precious, holistic and women live with a modified health condition in which they feel like living with a sword of Damocles over the head, but from which they have also developed strengths. After chemotherapy and radiotherapy completed, breast cancer is seen as a surmountable challenge that can strike anyone. Each of these categories will be expanded below.

Health perceptions

After receiving the breast cancer diagnosis and completed the prescribed treatment, the women interviewed are aware of the importance of health as mentioned by this participant: "Someone who has always been in good health does not know he is lucky. You must be sick once to see that this is not acquired and that it can happen to anyone". Health becomes more valuable after living with illness. Women with breast cancer now perceive health as a gift rather than property acquired or a tool to accomplish everyday tasks. Furthermore, they now perceive health holistically and not as a health-disease dichotomy. In this regard, the speech of a participant speaks: "Health is everything; physical, emotional, psychological, everything".

Although they do not see themselves as patients with breast cancer, women who participated in the study all agree to say that their perception of their health status is changed. Therefore, they feel that "when you have cancer, there is a sword of Damocles over the head hanging down and can reappear at any time". The women then develop a "annual life expectancy" with short-term projects rather than longterm as evidenced by the following statement: "I had to do everything in the same year. Do not give me long-term projects, I do not believe". In addition, they encourage each annual check-up, "You're lucky, you have one more year".

This new health changed in which women feel makes changes to body level. They say they feel healthy but diminished. "Decreased compared to the fact that all the consequences that may be there. With my arm, I was not much. I considered myself tired and psychologically disturbed. the transcript shows that the sense of feeling diminished comes from both physical limitations and psychological. The vast majority of women interviewed say that cancer "destroyed body image. The appearance was important for me and it's really something that still bothers me having the signs of cancer. Of course, these side effects ricochet on sexuality since "it is also playing level sensitivity. Put me naked on front of a man, I mind. I would tell him how much I think that my body is like Hiroshima bomb before I'm undressed, I'm sure".

Surprisingly, the women interviewed even affirm that they have developed "inner forces" following the transition perceptions of health status. I never thought I'd have the strength to get through this. I found it because I lived it". These forces will even push them to do things they would never have thought possible and give back to others as evidenced by these two women: "I need to get involved and I give to people. So I contacted the Canadian Cancer Society".

Perceptions of cancer

"I think I was more afraid of dying before I had breast cancer than when I got it". The perception that women had cancer before developing it gradually changed into a surmountable challenge as claimed by these women. "This is something that is surmountable". "I was petrified and it's not that bad. As the treatments, I saw that it was not that bad". By extension, the perception of invulnerability was transformed into a vision of "health for all" as verbalise this woman: "Before breast cancer it was for others, during treatments it was for me and now, after treatment, is for everyone". This quote demonstrates the changing perceptions of cancer when the woman spoke she believed escape to cancer when she was healthy, then she felt affected by breast cancer while she lived and finally how she lost the feeling of invulnerability after have this disease.

Health status perceptions shift: from invulnerability to living with a sword of damocles over the head

In this study, we found that before the diagnosis, the participants took their health for granted and felt invulnerable. “It only happens to other people” illustrates the feeling of invulnerability of healthy women. Also, before they got breast cancer, death was the first thing that had come to mind when the women thought of breast cancer. Being diagnosed with breast cancer triggered various internal changes in the women that we call ‘transition’. This transition begins when the official diagnosis of breast cancer is confirmed.

The end of the chemotherapy and radiation initiate the completion of the transition that is completed when the energy level is back. As the process draws to a close, the participants regain their health. However, this condition, which we call a ‘modified health status’, it is different because they have to live with the side effects of the treatments and, even more disturbing, with the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads at the idea that cancer could come back. Some of the women’s comments illustrate the feeling of living with this uncertainty: “It’s a shock when the treatments end! It cannot be. You just want to cry and say: ‘Don’t abandon me.’ You are never free from cancer”; “I will always have the sword of Damocles hanging over my head because I know that it could recur”. On the other hand, henceforth the women see cancer as a surmountable ordeal.

Discussions

The discussion of the results is set out in terms of perceptions of health status before and after the transition.

Perceptions of health and breast cancer before diagnosis

This research is innovative because it overcomes the lack of knowledge on the perceptions of health and disease in healthy people. Indeed, the studies reviewed in healthy people treat their perceptions of risk of developing a disease and respective causes [56]. Few studies exist on perceptions of the health of healthy people apart classics in sociology and anthropology as Herzlich [57] and Massé [58]. Our results corroborate previous findings reaffirming that, nearly four decades later, healthy people see themselves invulnerable and even define health as the absence of disease. However, we bring precision to the fact that in healthy people, but at risk of developing breast cancer because of their heredity, perceive health differently from those who have never rubbed the disease. They see themselves healthy, but they feel a sense of uncertainty about the occurrence of such a diagnosis that is manifested, among others, by regular monitoring to the doctor and assiduous mammograms. These results are in the same direction as those of studies conducted with women whose family members are suffering from cancer showing a positive association between family history of cancer and psychological distress [59-62]. This psychological distress increase further when a member of the immediate family is diagnosed with breast cancer [61]. However, it can vary depending on the experience of people [60]. Thus, a mother in remission from breast cancer will encourage and reassure her daughter at risk; phenomenon we have also found among our participants.

Perceptions of health and breast cancer after diagnosis

We noticed that perceptions of health are modulated throughout the disease trajectory to be seen as a precious gift and a brand holistically as breast cancer, meanwhile, is now perceived as an insurmountable ordeal even allowed women to find strength. Our results corroborate those of Al-Azri and Anagnostopoulos et al. [3,63] who point out that women with breast cancer are more optimistic about the chances of recovery that those in health. Anagnostopoulos and Spanea [63] state that healthy women are more pessimistic about the prognosis and overestimate the negative effects of cancer compared to those who are affected. We also believe, as Brix et al., Horgan, Holcombe et al., [64-67] that this change in perceptions and force development is attributed to the phenomenon of post-traumatic growth, observable in people who have experienced critical events, resulting in a change in priorities life, empathy for others who have a similar experience and increased self-confidence. All these changes were observed in participants in our study. We also add that these women constantly live with a sword of Damocles over the head of which is explained with the theory of uncertainty [68]. By cons, in this medium range theory, the authors argue that the uncertainty in chronic diseases is constant [69]. Instead, we observed that the level of uncertainty of women is the highest transition periods or when the trigger transition: the diagnosis of the disease and at the end of the transition: the end of treatment chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Strengths and limitations

This study is a preliminary exploration of the transition in health perceptions of women with breast cancer. By using a grounded theory design with its flexibility and openness to social processes, we were able to better define the steps and produce a preliminary model of this complex transition. The greatest strength of this study was the interviews with women at different points in the breast cancer trajectory. Compared to other studies done with homogenous samples targeting women at a specific time in their trajectory, this study was based on a theoretical sample. This strategy made it possible to explore a wide variety of experiences throughout the trajectory of the chronic disease and identify the steps in the health perceptions transition although it was not a longitudinal study.

Our nursing training and the first author’s clinical work experience in oncology may have influenced how the questions were formulated and helped to understand aspects related to the cancer management experience. Therefore, strength of this study is having paid special attention to elements related to our clinical and methodological experience, which may have affected our questions during data collection and interpretation. This setting aside of our preconceptions induced us to modify the interview guide, which in turn led to the discovery that the participants viewed breast cancer differently from health professionals.

Various methodological decisions increased the credibility of this study. First, the researchers used a rigorous and iterative research process that involved constantly comparing the literature review, the content of the interviews and the analysis. Other strategies also enhanced the credibility of the study, including co-analysis by the research team, the search for differing explanations with extreme cases including those of a healthy woman, and the in-depth description of the categories to illustrate the results [51]. Using these strategies, we were able to verify possible alternative models of the transition to be sure that the categories did indeed confirm the representation we derived from the participants’ vision. Finally, we had the participants themselves verify our understanding of the emerging data and the model of the results of our interpretation. This strategy enabled us to directly authenticate our understanding of the women’s experience with the women themselves, thus confirming the transferability of the results [70].

The interview transcripts, the field notes supplementing the data recorded during the interviews and the memos are all evidence that enables the research process to be reproduced and ensures the credibility of the results. The triangulation of the researchers and the fact that the results reflect the perspective of women at different times in the illness trajectory led to an in-depth description of the transition. These methods also contributed to the reliability of the transition presented. We made every effort to provide a detailed description of the research context and the participants’ characteristics to maximize the transferability of the results.

Despite these rigorous procedures, our study has some limitations. Although we reached a first level of empirical saturation in the selective coding with respect to the development of this model of the transition, it is possible that we did not reach the theoretical saturation to perfectly differentiate the concept of transition as a process from the concept of transition as a result. If we had continued our analysis, we may have found elements in the transition that would have completed our model since some categories are more developed than other. In addition, although the results presented are based on an exploration of the transition at multiple times in the trajectory, the sample contained very few women in palliative care and healthy women who carry the gene putting them at risk of developing breast cancer. Furthermore, in a desire to please the interviewer, some of the participants may have altered their answers.

Although grounded theory can be used to develop a middle range theory from data in a natural setting [43] used to clarify concepts and empirical indicators to guide practice, the interpretation of the data by the researchers still depends on their creativity and conceptual expertise. They recognize that, even if it is founded on a rigorous data collection and analysis approach, the health perceptions transition model is a human construct. As mentioned by Paillé [53], any theory is relative to the social and political context of its creation.

Knowledge transfer

Clinical fallout of this study is necessarily a better understanding of the transition from perceptions of health status during breast cancer trajectory. In addition, clinical nurse can support their clients in the development of adaptation strategies and thereby adapting care, provide information, support research relevant resources and also standardize perceptions stages of the transition and offer support to relatives. This modelling allows for health professionals working with women with breast cancer to deepen their systemic evaluation on perceptions of health and cancer, so to better interact with them, but most understand that the transition from perceptions the condition is a process that takes place throughout the course of chronic disease in order to redefine a sense of self and a new perception of health. They should also consider that these women are now living with the feeling stronger or weaker to have a sword of Damocles over the head.

Conclusions

This study aimed to explore the health status perceptions shift of women living with breast cancer according to the methodological orientation of the Grounded Theory. We propose a model to better understand how women struggle to make sense of their illness and find a life as normal as possible while managing the uncertainty that cancer reappears. The element used to define this modified health status is to feel diminished in their physical capacity but, above all, to live with a sword of Damocles over the head. The results of this analysis that perceptions of health and cancer are transformed during the disease's path in order to facilitate the passage of this experiment in which women are discovering forces such as managing their time, their symptoms, their health, their relationships and uncertainty and hope.

Grounded theory is defined as qualitative methodology involving the construction of theory through the analysis of empiric data.

References

- World Health Organization (2013) Breast Cancer. Page consultée à

- Canadian Cancer Society (2014) Cancer du sein. Page consultée à

- Al-Azri M, Al-Awisi H, Al-Moundhri M (2009) Coping with a diagnosis of breast cancer-literature review and implications for developing countries.Breast J 15: 615-622.

- Arathuzik MD (2009) Living with suffering: the process of coping with metastatic breast cancer pain. Oncology Nursing Forum 36: 34-34.

- Bakewell RT, Volker DL (2005) Sexual dysfunction related to the treatment of young women with breast cancer.Clin J OncolNurs 9: 697-702.

- Boehmke MM, Dickerson SS (2006) The diagnosis of breast cancer: transition from health to illness.OncolNurs Forum 33: 1121-1127.

- Cebeci F, YanginHB, TekeliA (2010) Determination of changes in the sexual lives of young women receiving breast cancer treatment: a qualitative study. Sexuality & Disability 28: 255-264

- Denieffe S, Gooney M (2011) A meta-synthesis of women's symptoms experience and breast cancer.Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 20: 424-435.

- Banning M, Tanzeem T (2013) Managing the illness experience of women with advanced breast cancer: hopes and fears of cancer-related insecurity.Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 22: 253-260.

- Saillant F (1988) Cancer et culture: produire le sens de la maladie. Montréal: Les Éditions Saint-Martin.

- Meleis AI (2010). Transitions theory. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Meleis AI, Sawyer LM, Im EO, HilfingerMessias DK, Schumacher K (2000) Experiencing transitions: an emerging middle-range theory.ANS AdvNursSci 23: 12-28.

- Chick N,Meleis AI (1986) Transitions: a nursing concern. Dans P. L. Chinn (Éd.), Nursing research methodology. New York: Aspen.

- Kralik D, Visentin K, van Loon A (2006) Transition: a literature review.J AdvNurs 55: 320-329.

- Meleis AI, Trangenstein PA (1994) Facilitating transitions: redefinition of the nursing mission.Nurs Outlook 42: 255-259.

- Bridges W (2004) Transitions: making sense of life's changes. Cambridge: Da Capo Press.

- Bridges W (2009) Managing transitions: making the most of change (3e Éd.) London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Fex A, Flensner G, Ek AC, Söderhamn O (2011) Health-illness transition among persons using advanced medical technology at home. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 25: 253-261.

- KralikD, van Loon AM (2009) Editorial: transition and chronic illness experience. Journal of Nursing & Healthcare of Chronic Illnesses 1:113-115.

- McEwen MM, Baird M, Pasvogel A,Gallegos G (2007) Health-illness transition experiences among Mexican immigrant women with diabetes. FamilyCommunity Health 30: 201-212.

- Doré C, Gallagher F, Saintonge L,Hébert M (2013) Breast cancer screening program: experiences of canadian women and their unmet needs. Health Care for Women International 34: 34-49.

- Drageset S, Lindstrøm TC, Underlid K (2010) Coping with breast cancer: between diagnosis and surgery.J AdvNurs 66: 149-158.

- Montgomery M (2010) Uncertainty during breast diagnostic evaluation: state of the science.OncolNurs Forum 37: 77-83.

- Beckjord EB, Glinder J, Langrock A,Compas BE (2009) Measuring multiple dimensions of perceived control in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Psychology Health, 24: 423-438.

- Bennett KK, Compas BE, Beckjord E, Glinder JG (2005) Self-blame and distress among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer.J Behav Med 28: 313-323.

- Coreil J, Wilke J, Pintado I (2004) Cultural models of illness and recovery in breast cancer support groups.Qual Health Res 14: 905-923.

- Loiselle C, Edgar L, Batist G, Lu J, Lauzier S (2010) The impact of a multimedia informational intervention on psychosocial adjustment among individuals with newly diagnosed breast or prostate cancer: a feasibility study. Patient Education &Counseling 80: 48-55

- Rosenzweig M, Donovan H, Slavish K (2010) The sensory and coping intervention for women newly diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer.J Cancer Educ 25: 377-384.

- Allen JD, Savadatti S, Levy AG (2009) The transition from breast cancer 'patient' to 'survivor'.Psychooncology 18: 71-78.

- Danhauer SC, Crawford SL, FarmerDF,Avis NE (2009) A longitudinal investigation of coping strategies and quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 371-379.

- Dalgaard KM, Thorsell G,Delmar C (2010) Identifying transitions in terminal illness trajectories: a critical factor in hospital-based palliative care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 16: 87-92.

- Grunfeld EA, Maher EJ, Browne S, Ward P, Young T, Vivat B, et al. (2006) Advanced breast cancer patients' perceptions of decision making for palliative chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology 24: 1090-1098

- Sand L, Olsson M, Strang P (2009) Coping strategies in the presence of one's own impending death from cancer.J Pain Symptom Manage 37: 13-22.

- BouchardL,Desmeules M (2011) Minorités de langue officielle du Canada. Égalesdevant la santé? Québec: Presses de l'Université du Québec.

- Hébert M, Côté M (2011) Étude descriptive rétrospective des perceptions de la maladie de femmes nouvellementatteintes d'un cancer du sein à la suite de leurstraitements en cliniqueambulatoired'oncologieL'infirmièrecliniciennepp:8: 1-8

- Massé R (2003)Éthique et santé publique. Enjeux, valeurs et normativité. Québec: Presses de l'Université Laval

- Park K, Chang SJ, Kim HC, Park EC, Lee ES, et al. (2009) Big gap between risk perception for breast cancer and risk factors: nationwide survey in Korea.Patient EducCouns 76: 113-119.

- Pilarski R (2009)Risk perception among women at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 18: 303-312.

- McCorry NK, Dempster M, Quinn J, Hogg A, Newell J, Moore M, Kirk SJ (2013) Illness perception clusters at diagnosis predict psychological distress among women with breast cancer at 6 months post diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology 22: 692-698.

- Petrie KJ, Weinman J (2012) Patients perceptions of their illness: The dynamo of volition in health care. Current directions in psychological science 21: 60-65.

- Corbin JM, Strauss AL (2008) Basics of qualitative research (Version 3e). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Crooks V A, Chouinard V,Wilton RD (2008) Understanding, embracing, rejecting: Women's negotiations of disability constructions and categorizations after becoming chronically ill. Social Science & Medicine 67: 1837-1846

- Strauss AL,Corbin JM (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research (2 éd.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Canadian Breast Cancer Fondation (2013) About Breast Cancer. Page consultée à

- MSSS(2014) Programme québécois de dépistage du cancer du sein : Gouvernement du Québec Repéré à http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/sujets/santepub/pqdcs/index.php?A_propos_du_programme.

- Dimitrova N, Tonev S, Coza D, Demetriu A, Gavric Z, Primic-Zakelj M, Coebergh JW (2014) Breast cancer in South-Eastern European countries: rising incidence and decreasing mortality at young and middle age. European Journal of Cancer 50: S81-S81.

- http://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/sujets/santepub/pqdcs/index.php?A_propos_du_programme

- Hou NQ, Huo DZ (2013) Breast cancer incidence rate in american women started to increase: Trend analysis from 2000 to 2009. Cancer Research 73: 1

- Santos Sda S, Melo LR, Koifman RJ, Koifman S (2013) Breast cancer incidence and mortality in women under 50 years of age in Brazil.Cad SaudePublica 29: 2230-2240.

- Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ (2013) Screening for breast cancer with mammography.Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001877.

- Pires AP (1997)Échantillonnage et recherche qualitative: essaithéorique et méthodologique. Dans J. Poupart, J.P. Deslauriers, L.H. Groulx, A. Laperrière, R. MayerA. P. Pires (Éds.), La recherche qualitative : Enjeuxépistémologiques et méthodologiques, 113-169. Boucherville: G. Morin.

- Denzin NK,Lincoln YS (2011) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research: SAGE Publications

- Henly SJ, Wyman JF, Findorff MJ (2011) Health and illness over time: the trajectory perspective in nursing science.Nurs Res 60: S5-14.

- Paillé P (1994)L'analyse par théorisationancrée Cahiers de recherchesociologique 23: 147-181.

- Plouffe MJ, Guillemette F (2013) La méthodologie de la théorisationenracinée. Dans J. Luckerhoff& F. Guillemette (Éds.), Méthodologie de la théorisationenracinée: fondements, procédures et usages (pp. 87-114). Québec: Presses de l'Université du Québec.

- FigueirasMJ, Alves NC (2007)Lay perceptions of serious illnesses: An adapted version of the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) for healthy people. Psychology & Health, 22: 143-158.

- Herzlich C (1969) Santé et maladie, analyse d'unereprésentationsociale. Paris: Éditions de l'EHESS.

- Massé R (1995) Culture et santé publique. Montréal: Gaëtan Morin Éditeur.

- Hébert M, Gallagher F, St-Cyr Tribble D (2016) Not feeling sick from breast cancer: A framework on health status perceptions transition process.Eur J OncolNurs 22: 85-94.

- Katapodi MC, Lee KA, FacioneNC,Dodd MJ (2004)Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: a meta-analytic review. Preventive Medicine 38: 388-402.

- Mellon S, Gold R, Janisse J, Cichon M, Tainsky MA, et al. (2008) Risk perception and cancer worries in families at increased risk of familial breast/ovarian cancer.Psychooncology 17: 756-766.

- Metcalfe KA, Quan ML, Eisen A, Cil T, Sun P, et al. (2013) The impact of having a sister diagnosed with breast cancer on cancer-related distress and breast cancer risk perception.Cancer 119: 1722-1728.

- Underhill ML, Lally RM, Kiviniemi MT, MurekeyisoniC,Dickerson SS (2012) Living my family's story: Identifying the lived experience in healthy women at risk for hereditary breast cancer. Cancer Nursing 35: 493-504.

- Anagnostopoulos F, Spanea E (2005) Assessing illness representations of breast cancer: a comparison of patients with healthy and benign controls.J Psychosom Res 58: 327-334.

- Brix SA, Bidstrup PE, Christensen J, Rottmann N, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Dalton SO (2013) Post-traumatic growth among elderly women with breast cancer compared to breast cancer-free women. ActaOncologica 52: 345-354

- Horgan O, Holcombe C, Salmon P (2011) Experiencing positive change after a diagnosis of breast cancer: a grounded theory analysis.Psychooncology 20: 1116-1125.

- Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV (2009) Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors.Psychol Health 24: 583-595.

- Sumalla EC, Ochoa C, Blanco I (2009) Posttraumatic growth in cancer: reality or illusion?ClinPsychol Rev 29: 24-33.

- Mishel MH (1988) Uncertainty in illness.Image J NursSch 20: 225-232.

- StraussAL, Corbin JM (2004) Les fondements de la recherche qualitative: Techniques et procédures de développement de la théoriesenracinée. Fribourg: Academic press Fribourg.

Relevant Topics

- Advances in Breast Cancer Treatment

- Alternative Treatments for Breast Cancer

- Breast Cancer Biology

- Breast Cancer Cure

- Breast Cancer Grading

- Breast Cancer Prevention

- Breast Cancer Radiotherapy

- Breast Cancer Research

- Breast Cancer Therapeutic & Market Analysis

- Breast Screening

- Cancer stem cells

- Fibrocystic Breast

- Hereditary Breast Cancer

- Inflammatory Breast Cancer

- Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

- Making Strides in Breast Cancer

- Mastectomy

- Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Molecular profiling

- Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer

- Smoking in Breast Cancer

- Terminal Breast Cancer

- Tumor biomarkers

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13112

- [From(publication date):

September-2016 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12190

- PDF downloads : 922