Research Article Open Access

A Case Study of Health Education from Nagano Prefecture in Japan: The Relationship between Health Education and Medical Expenses

Nakade K, Fujimori S, Watanabe T, Murata Y, Terasawa S, Jarpat SM, Adiatmika IPG, Adiputra IN, Muliarta IM and Terasawa K*Graduate School of Medicine, Shinshu University, Japan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Koji Terasawa

Graduate School of Medicine, Shinshu University, 3-1-1 Asahi Matsumoto

Nagano, 390-8621 Japan

Tel: 81-26-238-4213

Email: kterasa@shinshu-u.ac.jp

Received date: May 26, 2017; Accepted date: June 19, 2017; Published date: June 26, 2017

Citation: Nakade K, Fujimori S, Watanabe T, Murata Y, Terasawa S, et al. (2017) A Case Study of Health Education from Nagano Prefecture in Japan: The Relationship between Health Education and Medical Expenses. J Community Med Health Educ 7:529. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000529

Copyright: © 2017 Nakade K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Health promotion is not only the responsibility of the health sector, but extends from healthy lifestyles to wellbeing. We developed an active health program acquired ISO9001 (the International Organization for Standardization) in 2014. This health education program desired to Asian countries in cooperation with Asian Universities with the aim of increasing the health longevity of their populations.

Methods: The authors implemented a 10-month health program from May 2010 to Feb 2011 in Minowa town, Nagano prefecture, Japan. Participants of a health education group (HEG) in Minowa town included 41 elderly (age: 63.4 ± 5.9) individuals; 6 residents of Nagano city (aged 59.4 ± 7.9) acted as a control group (CG).

Results: The HEG participants showed significant improvement in weight, BMI, anthropometric measurements, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, physical fitness factors including sit-ups, sit-and-reach flexibility, eyes-open single-leg stance, 10 m obstacle walk and 6 min walk, LDL, and brain function as reflected in response time and error rates for go/no-go tasks. In contrast, CG had no significant differences in any items before and after the health education program period. Systolic blood pressure, sit-and-reach flexibility and 10 m obstacle walk of HEG participants showed a significant improvement compared to those of the CG. Medical expenses of HEG participants were significantly reduced for the 1st year and 2nd year after the health education program compared to those of the non-participants.

Conclusion: The systolic blood pressure, sit-and-reach flexibility and 10 m obstacle walk of HEG participants showed a significant improvement compared to those of the CG. Medical expenses of HEG participants were significantly reduced during health education and 1st and 2nd years after the health education program compared to those of non-participants.

Keywords

Health education; Pedometer; Brain function; Physical fitness; Blood chemistry

Background

In 1978, the Declaration of Alma-Ata was adopted at the International Conference on Primary Health Care. The primary health care approach has since been accepted as the key to achieving the goal of "Health for All" [1]. In 1986 in Ottawa, Canada, it was declared that health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over and improve their health [2]. Therefore, health promotion is not only the responsibility of the health sector, but ex-tends from healthy lifestyles to wellbeing. Japan has the world’s highest longevity rate. Citizens of Nagano enjoy the longest lifespan in Japan. Health promotion improvements are considered one reason for Japan being the world’s top country for longevity. We developed an active health program, which assesses energy expenditure, anthropometry, blood pressure, physical fitness, blood chemistry, and brain function as well as providing educational seminars on exercise, nutrition, and recreational activities such as hiking and cooking. This health education program acquired ISO9001 (the International Organization for Standardization) in 2014 and has been implemented in Nagano, Japan for 20 years. The authors desired to extend this health education program to Asian countries in cooperation with Asian Universities with the aim of increasing the health longevity of their populations. We hope to develop and implement substantial health education with continued cooperation with other country University, and to help promote a prosperous, health long-lived society.

Method

General method

The authors implemented a 10 month health program from May 2010 to Feb 2012 in Minowa town, Nagano prefecture, Japan. This was the latest version of this program developed in Japan, measuring energy expenditure using pedometers, anthropometry, blood pressure, physical fitness, blood chemistry and brain function. The participants in Minowa also participated in a series of recreational activities such as walking exercises, Tai Chi Chuan, hiking tours and cooking practice, as well as medical seminars on topics such as blood pressure, mouth care and nutritional balance. In addition, they performed 90 min strength and weight training once a week (Table 1). A total of 41 elderly participants (age: 63.4 ± 5.9 years (Mean ± SD); 14 men aged 66.2 ± 2.8 years and 27 women aged 61.9 ± 6.6 years) who participated in the health education group (HEG) in Minowa town completed the program. Six residents of Nagano city (age: 59.4 ± 7.9 years; 2 men aged 68.5 ± 3.5 years and 4 women aged 57.8 ± 8.1 years) served as a control group (CG). The CG subjects went about their daily lives as normal without participating in the health education program; we monitored them over a period of time similar to that of the Minowa program. The latest guidelines based on the Helsinki Declaration were adopted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Shinshu University (UMIN000009309). Written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

| Month | CTG program |

|---|---|

| 1 | Tai Chi Chuan and training once a week |

| 2 | The measurement before the health and training once a week |

| 3 | Closing ceremony |

| 4 | Opening Ceremony |

| 5 | The measurement before the health education, distribution of the pedometer and training once a week |

| 6 | Lecture of the important to health and training once a week |

| 7 | Practical recreation and training once a week |

| 8 | Hiking and training once a week |

| 9 | Lecture of nutrition and training once a week |

| 10 | Practical walking and training once a week |

| 11 | Lecture of blood pressure and training once a week |

| 12 | Lecture of dental health and training once a week |

Table 1: Program contents of the one-year health education in the CTG.

Pedometers

The number of steps walked and energy expenditure were measured from April 2010 to Feb 2011 in the Minowa program. The Weight Bearing Index (WBI) provided an approximate goal for the number of daily walking steps [3]. A recent pedometer model (Acos Inc., FS500) enabled pedometer data to be transferred and saved to a personal computer. Exercise steps are defined as steps taken during expenditure greater than 4 METS. Participants reported their results to a project leader when they gathered for monthly meetings.

Anthropometry and blood pressure

Anthropometric measurement adopted weight and body mass index (BMI) measurements. Weight measurement used body composition monitors with scales (Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd. JAPAN; HBF-359). Weight measurement was implemented at the time of fasting >10 h from the last meal. Maximum and minimum blood pressures were measured via auscultation (mercury sphygmomanometer, Kenzumedico 0601B001, Japan) after the study participants had been sitting for 15 min in a room with an ambient temperature of 25°C and relative humidity of approximately 50%.

Physical fitness

The physical test approved by the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [4] is composed of six physical assessments: Grip strength, sit-ups, sit-and-reach flexibility, eyes-open single-leg stance, 10-meter obstacle walk and a 6 min walk. Each participant's physical ability was assessed before and after the health education program.

Blood chemistry

The blood test used for the current study, which is recommended by the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [5] for the assessment of metabolic syndrome, measured four components: High density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), triglyceride, and fasting glucose. Participants underwent blood tests before and after the health education program.

Brain function

We adopted go/no-go tasks for the brain function test [6-8]. The go/no-go tasks consisted of three experimental stages: Formation, differentiation and reverse differentiation. First, in the formation stage, participants were instructed to squeeze a rubber ball in response to a red light. Second, during the differentiation stage, they squeezed a rubber ball in response to a red light, but not a yellow light, when a red or yellow light was randomly displayed. Third, during the reverse differentiation stage, participants squeezed a rubber ball in response to a yellow light but not a red light. In each of the differentiation and reverse differentiation stages participants completed 20 trials. Red and yellow lights were equally likely to be displayed 10 times each. In this paper, the term “forget” indicates an incorrect response when participants did not squeeze a rubber ball when it was to be squeezed. Conversely, the term “mistake” means an incorrect response when participants did squeeze the rubber ball when it was not supposed to be squeezed.

Medical expenses

Minowa town cooperated in checking the effect of this health education program for the two years following the program by comparing the medical expenses of participants with those of nonparticipants. We selected 29 subjects (age: 63.1 ± 3.4; 12 men aged 64.5 ± 1.7 years and 17 women aged 62.2 ± 4.0 years, age range: 50-69) who were enrolled in National Health Insurance out of the 41 participants of the HEG. The 2,768 comparison subjects, who were also enrolled in National Health Insurance, did not participate the health education program (NP; age: 62.7 ± 4.0 years; 1,380 men aged 62.9 ± 3.9 years and 1,388 women aged 62.5 ± 4.1 years, age range: 50-69). Next, because the initial medical expenses of HEG participants and NP subjects were different even before the health education program, we adjusted the initial expenses by removing NP subjects with high medical expenses and compared the medical expenses of the adjusted non-participants (ANP; total 2,725 aged 62.7 ± 4.0 years; 1,354 men aged 62.9 ± 3.9 years and 1,371 women aged 62.5 ± 4.1 years, age range: 50-69) with those of the 29 HEG participants.

Statistical analysis

A paired t-test was used to compare the results before and after participation in the health program. Comparison of pre and post health program in CG and HEG were analyzed via a two-way ANOVA replication. Medical expenses were compared using Welch's t-test. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0.1 Statistical Packages (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

Pedometer

Anthropometry and blood pressure: The CG had no significant difference in weight, BMI, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure before and after the health education program period. In contrast, HEG participants showed significant decreases in weight (before (B): 59.4 kg ± 1.8, after (A): 57.9 kg ± 1.8, t=4.0, p<0.000), BMI (B: 23.7 ± 3.5, A: 23.3 ± 3.3, t=2.4, p<0.019), systolic blood pressure (B: 139.8 ± 2.1, A: 125.2 ± 2.0, t=8.0, p<0.0001), and diastolic blood pressure (B: 87.3 ± 1.7, A: 78.7 ± 1.4, t=6.6, p<0.0001) before and after the health education program. Systolic blood pressure of the HEG participants was significantly different from that of the CG (F=4.4, p<0.039; Table 2).

| M/pre | M/post | P-value | C/pre | C/post | p-value | 2 way ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B+A | C+M | Intraction | |||||||||

| Body measurement | |||||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 59.4 ± 1.8 | 57.9 ± 1.8 | 0 | 53.3 ± 2.5 | 53.0 ± 2.8 | 0.467 | 0.573 | 0.122 | 0.868 | ||

| BMI | 23.7 ± 3.5 | 23.3 ± 3.3 | 0.019 | 21.3 ± 1.0 | 21.1 ± 1.1 | 0.332 | 0.585 | 0.022 | 0.922 | ||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 82.0 ± 1.6 | 81.8 ± 1.4 | 0.791 | 82.2 ± 3.4 | 82.7 ± 3.6 | 0.765 | 0.96 | 0.859 | 0.907 | ||

| Blood pressure | |||||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure | 139.8 ± 2.1 | 125.2 ± 2.0 | 0 | 126.7 ± 7.6 | 132.2 ± 13.2 | 0.432 | 0 | 0.511 | 0.036 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure | 87.3 ± 1.7 | 78.7 ± 1.4 | 0 | 75.8 ± 2.9 | 75.7 ± 5.8 | 0.958 | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.189 | ||

| Physical fitness test | |||||||||||

| Hand Grip Strength (kg) | 30.3 ± 1.5 | 31.4 ± 1.6 | 0.112 | 27.7 ± 2.5 | 27.5 ± 2.5 | 0.94 | 0.637 | 0.262 | 0.823 | ||

| Sit Up (times) | 10.7 ± 1.0 | 10.7 ± 1.0 | 0 | 9.5 ± 3.3 | 8.5 ± 4.1 | 0.624 | 0.027 | 0.066 | 0.223 | ||

| Sit and reach flexibility (cm) | 39.1 ± 1.2 | 45.8 ± 1.3 | 0 | 37.2 ± 5.7 | 33.3 ± 3.8 | 0.529 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.036 | ||

| Eyes open single leg stance (sec) | 84.8 ± 7.0 | 104.3 ± 5.1 | 0.003 | 92.5 ± 13.1 | 83.7 ± 20.3 | 0.675 | 0.086 | 0.538 | 0.277 | ||

| 10m Obstacle walk (sec) | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 0 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.479 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | ||

| 6miniutes walk (m) | 597.5 ± 6.4 | 658.5 ± 9.4 | 0 | 663.3 ± 22.6 | 663.3 ± 22.6 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.354 | 0.414 | ||

| Blood test | |||||||||||

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dl) | 100.0 ± 1.7 | 98.5 ± 2.8 | 0.473 | 101.2 ± 4.3 | 95.5 ± 7.4 | 0.295 | 0.512 | 0.85 | 0.651 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | 5.36 ± 0.1 | 5.44 ± 0.1 | 0.021 | 5.77 ± 0.1 | 5.90 ± 0.1 | 0.082 | 0.351 | 0.001 | 0.817 | ||

| HDL (mg/dl) | 63.3 ± 2.6 | 64.0 ± 2.7 | 0.59 | 65.8 ± 7.4 | 67.2 ± 7.9 | 0.715 | 0.822 | 0.6 | 0.955 | ||

| LDL (mg/dl) | 126.9 ± 4.4 | 119.2 ± 3.8 | 0.022 | 132.3 ± 13.9 | 126.2 ± 14.1 | 0.153 | 0.183 | 0.464 | 0.925 | ||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 103.3 ± 7.4 | 90.1 ± 6.6 | 0.101 | 121.3 ± 23.1 | 105.3 ± 18.7 | 0.331 | 0.152 | 0.24 | 0.922 | ||

| Brain function test(go/no-go task) Response | |||||||||||

| Formation (msec) | 261.1 ± 9.7 | 233.6 ± 6.6 | 0.003 | 260.3 ± 25.2 | 230.7 ± 11.1 | 0.262 | 0.013 | 0.913 | 0.948 | ||

| Differentiation (msec) | 381.3 ± 7.9 | 367.8 ± 10.1 | 0.076 | 411.8 ± 28.0 | 376.5 ± 21.7 | 0.418 | 0.179 | 0.275 | 0.538 | ||

| Revers Differentiation (msec) | 419.5 ± 9.3 | 401.4 ± 10.7 | 0.035 | 424.2 ± 28.0 | 431.0 ± 34.9 | 0.882 | 0.292 | 0.412 | 0.55 | ||

| Average (msec) | 374.7 ± 7.2 | 356.9 ± 8.6 | 0.005 | 388.8 ± 28.8 | 371.6 ± 21.2 | 0.633 | 0.081 | 0.399 | 0.941 | ||

| Times | |||||||||||

| Total number of Forgets (Times) | 0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.168 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.385 | 0.629 | ||

| Total number of Mistakes (Times) | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.021 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.317 | 0.204 | 0.749 | 0.125 | ||

| Total number of Errors (Times) | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 0.062 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.317 | 0.365 | 0.945 | 0.169 | ||

Table 2: Comparison of pre and post health program in control and Minowa.

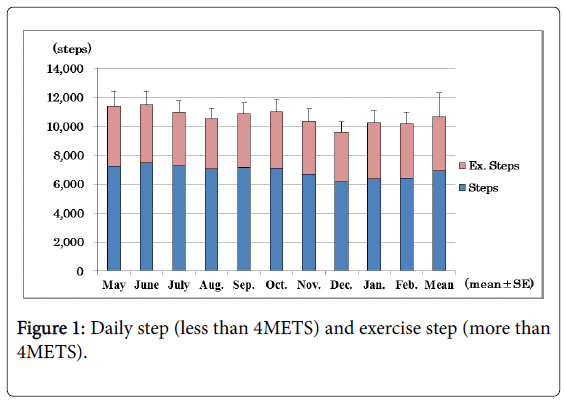

Figure 1 shows the average number of walked and exercise steps for each month (May: walking steps, 11,374.4 ± 1,021.8 (mean ± SE), exercise steps, 4,165.2 ± 485.0; June: 11,498.9 ± 897.9, 4,006.0 ± 437.0; July: 10,948.1 ± 798.0, 3,673.9 ± 399.1; August: 10,510.1 ± 713.6, 3,448.5 ± 357.4; September: 10,858.5 ± 738.3, 3,701.4 ± 363.1; October: 10,994.9 ± 856.4, 3,868.3 ± 402.2; November: 10,358.7 ± 831.5, 3,658.7 ± 394.7; December: 9,585.0 ± 737.8, 3,413.1 ± 357.0; January: 10,228.2 ± 851.6, 3,852.4 ± 420.4; February: 10,164.0 ± 787.5, 3,727.0 ± 386.6; Total: 10,652.1 ± 1,655.0, 3,705.5 ± 363.0). The average steps walked and exercise steps gradually increased in June and October. However, both walking and exercise steps decreased in August and December.

Physical fitness

The CG had no significant differences in any items before and after the health education program period. In contrast, HEG participants showed significant improvement in sit-ups (B: 10.7 ± 1, A: 14.5 ± 1.1, t=-8.4, p<0.0001), sit-and-reach flexibility (B: 39.1 ± 1.2, A: 45.8 ± 1.3, t=-8.6, p<0.0001), eyes-open single-leg stance (B: 84.8 ± 7.0, A: 104.3 ± 5.1, t=-3.1, p<0.003), 10-meter obstacle walk (B: 7.4 ± 0.1, A: 5.9 ± 1.0, t=22.1, p<0.0001) and 6 min walk (B: 597.5 ± 6.4, A: 658.5 ± 9.4, t=-13.6, p<0.0001) before and after the health education program. The sit-and-reach flexibility (F=4.5, p<0.036) and 10-meter obstacle walk (F=8.7, p<0.001) results of HEG participants showed significant improvement compared to those of the CG (Table 2).

Blood chemistry

The CG showed no significant difference in HDL, LDL, triglyceride and fasting glucose before and after the health education program period. HEG participants showed no significant improvement in HDL, triglyceride or fasting glucose; however LDL (B: 126.9 ± 4.4, A: 119.2 ± 3.8, t=2.4, p<0.022) was significantly improved after the health education program (Table 2).

Brain function

The CG had no significant differences in any items for go/no-go tasks before and after the health education program period. In contrast, HEG participants showed significant differences in response times for the formation task (B: 261.1 ± 9.7, A: 233.6 ± 6.6, t=3.2, p<0.003), response times for the reverse differentiation task (B: 419.4 ± 9.3, A: 401.4 ± 10.7, t=2.2, p<0.035), total response times (B: 373.7 ± 7.2, A: 356.9 ± 8.6, t=3.0, p<0.046), number of mistakes for the differentiation task (B: 1.8 ± 0.2, A: 1.2 ± 0.2, t=2.9, p<0.007), and the total number of “forgets” and mistakes (B: 2.4 ± 0.3, A: 1.8 ± 0.2, t=2.0, p<0.049) before and after the health education program (Table 2).

Medical expenses

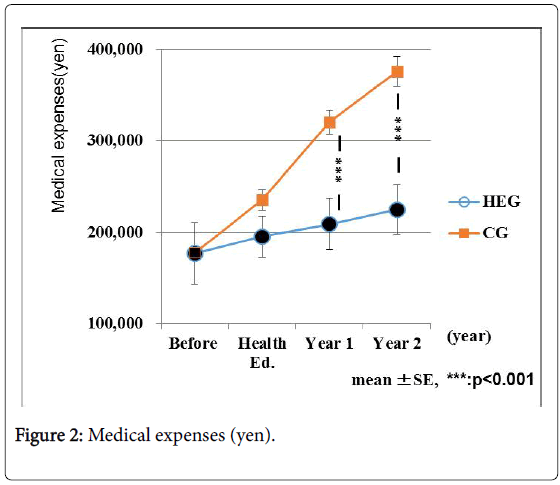

Without adjustment of the initial values of medical expenses, the comparison would have resulted in no significant difference between the NP and HEG participants before the program (NP: 234,069 ± 14,950 yen, HEG: 176,807 ± 33,453 yen, Dif: 57,262 yen). However, significantly higher medical expenses were observed for the NP compared to HEG participants during the health education program (NP: 268,026 ± 15,252 yen, HEG: 195,446 ± 22,744 yen, Dif.: 72,579 yen, t=-2.2, p<0.05), 1st year after (NP: 302,479 ± 14,882 yen, HEG: 209,255 ± 28,348 yen, Dif.: 93,224 yen, t=-2.9, p<0.01) and 2nd years after (NP: 405,802 ± 16,391 yen, HEG: 224,867 ± 26,954 yen, Dif.: 180,936 yen, t=-5.0, p<0.0001) the pro-gram. Therefore, we excluded the non-participants who had exceptionally high medical expenses in order to make a comparison using similar initial medical expenses. There was no significant difference between ANP and HEG participants before (ANP: 177,883 ± 7,084 yen, HEG: 176,807 ± 33,453 yen, Dif.: 1,076 yen) and during the health education pro-gram (ANP: 235,584 ± 10,979 yen, HEG: 195,446 ± 22,744 yen, Dif.: 40,138 yen). However significant differences were observed between the CG and HEG 1st year (ANP: 320,401 ± 13,078 yen, HEG: 209,255 ± 28,348 yen, Dif.: 111,146 yen; t=-3.6, p<0.001) and 2nd years (DNP: 376,387 ± 16,391 yen, HEG: 224,867 ± 26,954 yen, Dif: 151,520 yen; t=-4.8, p<0.0001) after the health education program (Figure 2).

Discussion

Pedometers

In this study, wearing pedometers may have encouraged participants to increase their walking distance and time. From the perspective of health education, it is important to encourage participants to increase the quality and quantity of exercise [9-11]. For example, research suggests that cardiac rehabilitation patients need to take at least 6,500 steps per day to obtain health benefits [12]. In addition, educational intervention is necessary to improve the quality of future programs. The average walking steps and exercise steps of HEG participants increased in June and October, whereas those averages decreased in August and December. The de-creased number of steps is probably due to difficulties with walking in hot and cold weather: In Nagano, the average summer temperature is approximately 31°C and winter is snowy with an average temperature of approximately -1.6°C. Nevertheless, the average number of steps walked by HEG participants was 10,652.1 ± 1,655.0 or more in all months except December. It is challenging to walk 10,000 steps or more per day; perhaps the encouragement of the trainer worked well.

Anthropometry and blood pressure

In addition to exercise, therapeutic lifestyle changes are recommended. It has been shown that dynamic endurance exercise decreases body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and blood pressure [13,14]. HEG participants were asked to perform 90 min strength and weight training once a week and to exercise by walking more than 10,000 steps each day. As a result, weight, BMI, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure after the health education program had significantly decreased compared to before the program.

Physical fitness

The practice of physical measurement differs from country to country. The physical fitness test employed with this study comprises six physical measurements and is designed for healthy elderly people from 65 to 79 years old [4]. In the CG, there were no significant differences in grip strength, sit-ups, sit-and-reach flexibility, eyes-open single-leg stance, 10-meter obstacle walk or 6 min walk before and after the health education program period. In contrast, while there was no significant difference in grip strength, HEG participants showed significant improvement in sit-ups, sit-and-reach flexibility, eyes-open single-leg stance, 10-meter obstacle walk and 6 min walk after the health education program compared to before the program. These results also may be effects by the strength and weight training and walk 10,000 steps or more per day.

Blood chemistry

It is a well-known fact that metabolic syndrome produces a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors including abdominal obesity, impaired glucose control, hypertension and dyslipidemia [15]. It has been reported that blood composition, as a standard measure for metabolic syndrome, is improved with exercise [16]. Although HDL, Triglyceride and fasting glucose values improved in the HEG, the improvements were not significant. However, LDL values improved significantly with strength and weight training and walking exercise.

Brain function

Performance of go/no-go tasks, which are frequently used to investigate response inhibition, requires a variety of cognitive components beside response inhibition. Response inhibition is an essential executive function implemented by the prefrontal cortex [6,17,18]. A previous study [19-22] using go/no-go tasks reported that reaction time was faster and error rates were reduced when participants continued to exercise for 10 months, taking an average of 7,000 steps per day. The two year continuation of this walking exercise seemed to further result in faster reaction times and decreased error rates. In the current study, The CG had no significant differences in any items for go/no-go tasks before and after the health education program period. In contrast, HEG participants showed significant improvement in response times for formation tasks, response times for reverse differentiation tasks, total response times, mistake rates for differentiation tasks and total “forget” and mistake rates before and after the health education program. These results show that the brain function was improved by 90 min strength and weight training once a week and challenging to walk 10,000 steps or more per day.

Medical expenses

Without adjustment of the initial values of medical expenses, significantly higher medical expenses were observed for the NP compared to HEG participants during (Dif.: 72,579 yen), 1 year after (Dif.: 93,224 yen) and 2 years after (Dif.: 180,936 yen) the program. When we adjusted the initial value for medical expenses of the participants and non-participants of the health education program, significant differences were observed between the DNP and HEG 1 year (Dif.: 111,146 yen) and 2 years (Dif.: 151,520 yen) after the health education pro-gram. The participants of the health education program had significantly lower medical expenses than did nonparticipants. Non-adjusted initial values for NP medical expenses were higher than the adjusted (ANP) initial values; nevertheless no significant differences were observed between the 1st and 2nd years for either (NP and ANP) group. Taken together, these results suggest the importance of health education. However there are few subjects, we must have increase subjects in the future study.

Conclusion

Participants of a health education group (HEG) in Minowa town included 41 elderly (age: 63.4 ± 5.9) individuals; 6 residents of Nagano city (age: 59.4 ± 7.9) acted as a control group (CG). The average number of steps walked daily by participants in the HEG was 10,652.1 ± 1,655.0. HEG participants showed significant improvement in anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, physical fitness, blood chemistry, and brain function. In contrast, CG participants had no significant differences in any items before and after the health education program period. The systolic blood pressure, sit-and-reach flexibility and 10-meter obstacle walk of HEG participants showed a significant improvement com-pared to those of the CG. Medical expenses of HEG participants were significantly reduced during health education and 1st and 2nd years after the health education program compared to those of non-participants.

Funding

This research is supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Scientist of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Houga: 26560380, Kiban A: 25257101).

References

- International conference on primary health care (1978) Declaration of Alma-Ata. WHO Chron 32: 428-430.

- WHO (1986) Ottawa charter for health promotion. World health organization, Geneva.

- Kikawa A, Yamamoto T (1991) The functional muscular strength measurement: Rating system of weight bearing index. The Japanese Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine 10: 463-468.

- Ministry of Education (1999) Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2000) The comprehensive reform of social security and tax.

- Masaki T, Moriyama G (1971) Study on types of human higher nervous activity. Tokyo University of Science press 4: 69-81

- Terasawa K, Tabuchi H, Yanagisawa H, Yanagisawa A, Shinohara K, et al. (2014) Comparative survey of go/no-go results to identify the inhibitory control ability change of Japanese children. Biopsychosoc Med 8: 14.

- Terasawa K, Misaki S, Murata Y, Watanabe T, Terasawa S, et al. (2014) Relevance between Alzheimer’s disease patients and normal subjects using go/no-go tasks and Alzheimer assessment scores. J Child Adolesc Behav 2: 162.

- Adams MA, Sallis JF, Norman GJ, Hovell MF, Hekler EB, et al. (2013) An adaptive physical activity intervention for overweight adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 8: e8290.

- Bickmore TW, Silliman RA, Nelson K, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. (2014) A randomized controlled trial of an automated exercise coach for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 61: 1676-1683.

- Thomson JL, Landry AS, Zoellner JM, Connell C, Madson MB, et al. (2014) Participant adherence indicators predict changes in blood pressure, anthropometric measures, and self-reported physical activity in a lifestyle intervention. Health Educ Behav 1-8.

- Blanchard CM, Giacomantonio N, Lyons R, Cyr C, Rhodes RE, et al. (2014) Examining the steps-per-day trajectories of cardiac rehabilitation patients: A latent class growth analysis perspective. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 34: 106-113.

- Izquierdo R, Lagua CT, Meyer S, Ploutz-Snyder RJ, Palmas W, et al. (2010) Telemedicine intervention effects on waist circumference and body mass index in the IDEA Tel project. Diabetes Technol Ther 12: 213-220.

- Ryan AS, Ge S, Blumenthal JB, Serra MC, Prior SJ, et al. (2014) Aerobic exercise and weight loss reduce vascular markers of inflammation and improve insulin sensitivity in obese women. J Am Geriatr Soc 62: 607-614.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, et al. (2005) Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American heart association/National heart, lung, and blood institute scientific statement. Circulation 112: 2735-2752.

- Alvarez LC, Ramírez-Campillo R, Flores OM, Hen-ríquez-Olguín C, Campos JC, et al. (2013) Metabolic response to high intensity exercise training in sedentary hyperglycemic and hypercholester-olemic women. Rev Med Chil 141: 1293-1299.

- Chikazoe J (2010) localizing performance of Go/Nogo tasks to prefrontal cortical subregions. Curr Opin Psychiatry 23: 267-272.

- Diamond A (2013) Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol 64: 135-168.

- Nakade K, Abe K, Fujiwara T, Terasawa K, Okuhara M, et al. (2009) The influence of two different health education program on GO/NO-GO tasks, physical fitness tests and blood tests. Japan Society of Physical Anthropology 14: 143-150.

- Watanabe T, Terasawa K, Nakade K, Murata Y, Terasawa S, et al. (2015) Influence of two different health promotion programs on walking steps, anthropometry, blood pressure, physical fitness, blood chemistry and brain function: I J Med and Heal Sci 5: 170-181.

- Murata Y, Nemoto K, Kobayashi I, Miyata Y, Terasawa S, et al. (2015) Effect of a two year health program on brain function, physical fitness and blood chemistry. J Community Med Health Educ 5: 349.

- Suchinda JM, Wanna S, Supalax C, Sirintorn C, Supunnee T, et al. (2015) Comparing the effectiveness of health program in thailand and japan. J Nurs Care 4: 298.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5149

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Jul 09, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 4191

- PDF downloads : 958