A Case of Bifid Mandibular Condyle

Received: 04-Oct-2017 / Accepted Date: 19-Oct-2017 / Published Date: 26-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2167-7964.1000278

Abstract

Bifid mandibular condyle is a rare anatomic anomaly that can result from congenital malformation, trauma, infection or tumor. We report a case of bifid mandibular condyle found after head injury. A bifid mandibular condyle was seen on the computed tomographic scan of a 41-year-old man after a car accident. The patient had asymmetry in the condylar angle and length of the condylar neck, and anomaly of occlusion resulting from many residual roots with deep caries. Mouth-opening and mandibular movements were normal, however, the presence of temporomandibular joint symptoms was unclear because of the patient’s unconsciousness at the time of the scan. The bifid mandibular condyle could have resulted from a bicycle accident when the patient was 7 years of age, based on information from the patient’s family.

Keywords: Bifid mandibular condyle; Temporomandibular joint; Anomaly; Traumatic

Introduction

Bifid mandibular condyle is rare anatomic anomaly that can result from congenital malformation, trauma, infection or tumor. Since Hrdli?ka first reported the condition in skull specimens in 1941, there have been 50 reports concerning bifid mandibular condyles [1-15]. The degree of condylar head separation is variable, with some cases having only a 1-2-mm indentation in the condylar head, while others have complete separation of the heads. There are fewer reported cases of complete condylar head separation.

Herein we report a case of bifid mandibular condyle with complete separation found on computed tomography scan taken after a head injury.

Case Report

A 41-year-old Japanese man presented to the Trauma and Acute Critical Care Center of Osaka University Hospital after being hit by a large truck traveling at 10-20 km/hr. The patient’s consciousness level according to the Glasgow Coma Scale was 10 (E4: Eye Opening was spontaneous, V1: Best Verbal Response was nil, M5: Best Motor Response was localising) at presentation. The patient was diagnosed with skull fracture, acute right subdural hematoma, acute left extradural hematoma, cerebral contusion, right femoral open fracture and left tibiofibular fracture. When a Computed Tomography (CT) scan revealed abnormality of the right condylar head, the patient was referred to our unit.

The patient had slight facial asymmetry with chin deviation to the right side, and anomaly of occlusion resulting from many residual roots with deep caries. Mouth-opening and mandibular movements were normal; the presence of temporomandibular joint symptoms was unclear because of the patient’s lack of consciousness caused by the accident.

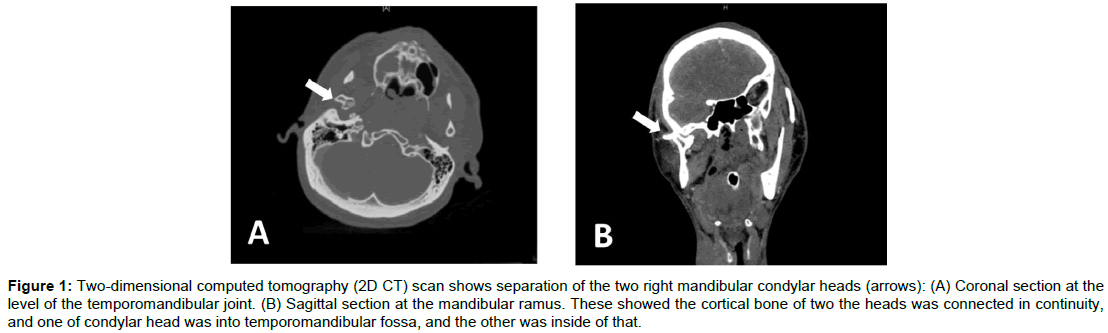

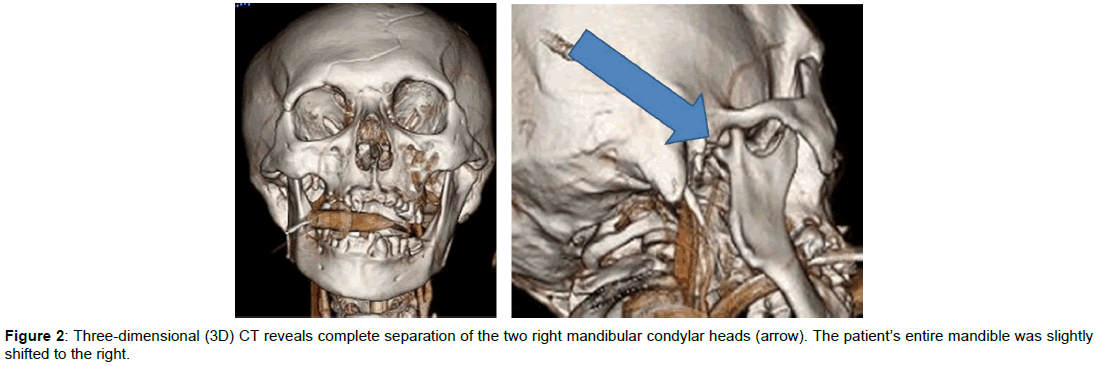

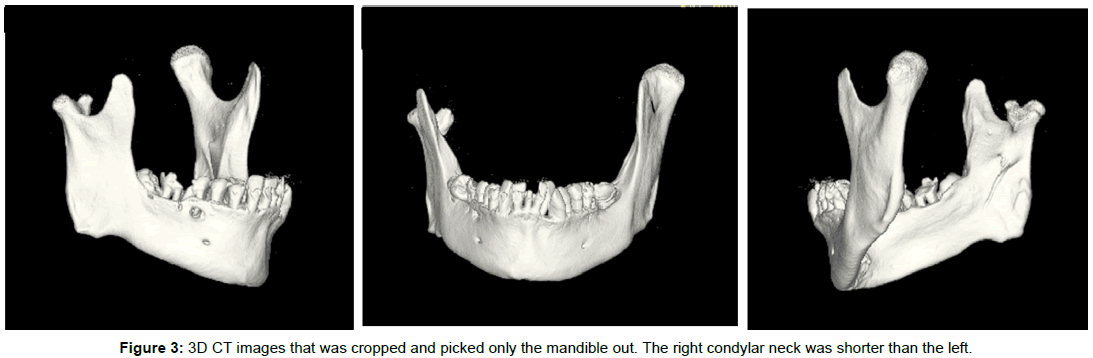

On CT scan, complete separation of the right mandibular condyle into two heads was observed. Two-dimensional (2D) images showed the cortical bone of two the heads was connected in continuity, and one of condylar head was into temporomandibular fossa, and the other was inside of that (Figure 1A and B). The patient’s entire mandible was slightly shifted to the right and the right condylar neck was shorter than the left (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Two-dimensional computed tomography (2D CT) scan shows separation of the two right mandibular condylar heads (arrows): (A) Coronal section at the level of the temporomandibular joint. (B) Sagittal section at the mandibular ramus. These showed the cortical bone of two the heads was connected in continuity, and one of condylar head was into temporomandibular fossa, and the other was inside of that.

According to the medical history provided by the patient’s family, he had been in a bicycle accident at the age of seven, and had fractured his mandibular condyle; although whether the fracture had been on the left or right was unclear. Treatment had been judged unnecessary and the patient had not experienced pain or dysfunction of mouthopening or chewing. The patient developed schizophrenia at about 25 years of age, when he was a university student. He had a history of hospitalization for treatment of schizophrenia, but was being treated as an outpatient with follow-ups at a psychiatry hospital every 2-3 weeks at the time of the accident.

The bifid mandibular condyle likely resulted from the patient’s bicycle accident in childhood.

As treatment, the residual roots, which were likely to become a source of infection, were extracted, and other caries treated. Open reduction and internal fixation of the leg fractures was performed under general anesthesia at the Trauma and Acute Critical Care Center on the eighth day after injury. However, the patient’s consciousness did not improve and he was transferred to another hospital for care for 44 days after the accident.

Discussion

Bifid mandibular condyle is thought to result from congenital malformation, trauma, infection or tumor. In this case, bifid mandibular condyle was likely caused by trauma, because the patient had experienced fracture of the condylar head as a child.

Condylar fractures can be horizontal or sagittal. Many horizontally fractured condyles have spontaneous repositioning and remodeling of the fractured fragments, or complete resorption of the fractured condyle and regeneration of a new condyle, so few horizontally fractured condyles develop bifid deformity [3,16-21]. In many cases of horizontally fractured condyles, some healing occurs from the bone fracture to the joint, because these fractures are treated with intermaxillary fixation to correct occlusal disharmony. Wu et al. reported that two of three bifid condyles cause by trauma were sagittally fractured condyles; there are other reports of bifid condyle after sagittal facture [3,15,21].

Our patient likely had a horizontally fractured condyle because there was asymmetry of the mandible on the side with the bifid condyle. Healing as a bifid condyle is rare after horizontal condylar fracture. In this case occlusal correction was likely unsuccessful because the patient was going through a growth spurt at the time of his injury, resulting in a bifid condyle. Cancellous bone union was observed on CT scan, so the condition likely resulted from trauma at a young age.

Because most bifid condyles are asymptomatic, treatment is not pursued except in cases with ankylosis after bone fracture [7,13,14,19,21]. Bifid condyles are often found incidentally on CT scan; there are no reports of treatment of bifid condyles without ankylosis. In this case, because there was no limitation of mouth opening and the patient’s symptoms could not be checked, we did not treat the bifid condyle. However, if the patient’s consciousness had recovered and he had reported symptoms, treatment for the jaw deformity might have been necessary because of mandibular asymmetry. In the past the mandibular condyle was observed only with two-dimensional X-rays, bifid condyles were often overlooked because of difficulty interpreting radiographs. The recent increase in the use of CT will result in more incidental findings of bifid condyle, as in our case.

References

- Hrdli?ka A (1941) Lower jaw: double condyles. Am J Phys Anthrop 28: 75-89.

- Anderson MF, Alling CC (1965) Subcondylar factures in young dogs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 19: 263-268.

- Antoniades K, Karakasis D, Elphtheriades J (1993) Bifid mandibular condyle resulting from a sagittal fracture of the condylar head. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 31: 124-126.

- Antoniades K, Hadjipetrou L, Antoniades V, Paraskecopoulos K (2004) Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 97: 535-538.

- Boyne PJ (1967) Osseous repair and mandibular growth after subcondylar fractures. J Oral Surg 25: 300-309.

- Cho BH, Jung YH (2013) Nontraumatic bifid mandibular condyles in asymptomatic and symptomatic temporomandibular joint subjects. Imaging Sci Dent 43: 25-30.

- Daniels JSM, Ali I (2005) Post-traumatic bifid condyle associated with temporomandibular joint ankylosis: Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 99: 682-688.

- Loh FC, Yeo JF (1990) Bifid mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 69: 24-27.

- Menezes AV, de Moraes Ramos FM, de Vasconcelos-Filho JO, Kurita LM, de Almeida SM, et al. (2008) The prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle detected in a Brazilian population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 37: 220-223.

- Miloglu O, Yalcin E, Buyukkurt MC, Yilmaz AB, Harorli A (2010) The frequency of bifid mandibular condyle in a Turkish patient population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 39: 42-46.

- Nah KS (2012) Condylar bony changes in patients with temporomandibular disorders: a CBCT study. Imaging Sci Dent 42: 249-253.

- Quayle AA, Adams JE (1986) Supplemental mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 24: 349-356.

- Rehman TA, Gibikote S, Ilango N, Thaj J, Sarawagi R, et al. (2009) Bifid mandibular condyle with associated temporomandibular joint ankylosis: a computed tomography study of the patterns and morphological variations. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 38: 239-244.

- ?ahaman H, Et?z OA, ?ekerci AE, Et?z M, ?i?man Y (2011) Tetrafid mandibular condyle: a unique case report and review of the literature. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 40: 524-530.

- To EW (1989) Mandibular ankyloses associated with a bifid condyle. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 17: 326-328.

- Leake D, Doykos J, Habal MB, Murray JE (1971) Long-term follow-up of fractures of the mandibular condyle in children. Plastic Reconstr Surg 47: 127-132.

- Sahm G, Witt E (1989) Long-term results after childhood condylar fractures. A computer-tomographic study. Eur J Orthod 11: 154-160.

- Kahl B, Fischbach R, Gerlach KL (1995) Temporomandibular joint morphology in children after treatment of condylar fractures with functional appliance therapy: a follow-up study using computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 24: 37-45.

- To EW (1989) Supero-lateral dislocation of sagittally split bifid mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 27: 107-113.

- Walker RV (1960) Traumatic mandibular condylar fracture dislocations, effect on growth in the macaca rhesus monkey. Am J Surg 100: 850-863.

- Wu XG, Hong M, Sun KH (1994) Severe osteoarthrosis after fracture of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52: 138-142.

Citation: Isomura ET, Kobashi H, Tanaka S, Enomoto A, Kogo M (2017) A Case of Bifid Mandibular Condyle. OMICS J Radiol 6: 278. DOI: 10.4172/2167-7964.1000278

Copyright: © 2017 Isomura ET, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7358

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Mar 29, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 6455

- PDF downloads: 903