Research Article Open Access

A Brief Meaning-focused Intervention for Advanced Cancer Patients in Acute Oncology Setting

Lai TK Theresa1*, Mok Esther2, Wong TP Mike3, Cheung W Y1, Lo CK1 and Yau CC11Department of Oncology, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

2Department of Nursing, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China

3Clinical Psychology, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Lai TK Theresa

Department of Oncology (Palliative care)

Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Tel: 852-29902486

E-mail: laitk@ha.org.hk

Received date: May 11, 2012; Accepted date: September 10, 2012; Published date: September 12, 2012

Citation: Lai TKT, Mok E, Wong TPM, Cheung WY, Lo CK, et al. (2012) A Brief Meaning-focused Intervention for Advanced Cancer Patients in Acute Oncology Setting. J Palliative Care Med S1:008. doi: 10.4172/2165-7386.S1-008

Copyright: © 2012 Lai TKT, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Background: A large number of advanced cancer patients are in great despair, there is no longer seen meaning or value in their life and want to hasten their death. The purpose of the study was to explore the impact of a brief, individualized meaning-focused intervention for advanced cancer patients.

Methods: This study employed a single blinded randomized controlled trial design, and measures taken at baseline, immediately after intervention, and two week after intervention. Quality-of-life concerns in the end of life questionnaire (QOLC-E) will be used as the measurement. There are 2 sessions for the intervention. The first session involves a semi-structured interview that facilitates the search for meaning. The second session is to review, verify, and clarify the findings from the first session with the patients. Qualitative data on perception of the intervention was obtained for the treatment group after completion of the intervention.

Results: The score of existential distress domain, quality of life and overall scale of QOLC-E of meaning-focused intervention group were significantly higher than the control group (p ≤ 0.05). The results showed significantly improved quality of life in existential distress domain of meaning-focused intervention group. In addition the negative emotion domain, support domain, value in life domain, existential distress domain, and quality of life and over scale of QOLC-E of intervention group improved significantly after intervention (p ≤ 0.01). Apart from the improvement in the intervention group, support domains of both groups in the third measurement were improved after the study (p ≤ 0.05). Qualitative data also supported that the intervention was effective and common meaningful events for advanced cancer patients were discovered during the processes.

Conclusion: The findings `show the brief meaning-focused on intervention helps to improve existential wellbeing and quality of life for advanced cancer patients. It represents the potential effectiveness and efficient intervention is feasible for implementation by healthcare professionals.

Keywords

Meaning-focused intervention; Existential wellbeing; Quality of life; Cancer patients

Introduction

Cancer is a serious illness that is familiar to most people. There is an increasing trend of people diagnosed with cancer is evident in Hong Kong. Malignant neoplasm has always been the leading cause of death in Hong Kong [1]. In addition to its physical toll, cancer has a devastating emotional impact on individuals living an advanced stage of this disease. The threat to life can challenge people’s beliefs about their life and sense of wellbeing [2].

In Hong Kong, a large number of advanced cancer patients are in great despair and want to hasten their death. Ho and Tay [3] found the rate of suicide in the oncology ward double the average rate in the general wards of public hospitals in Hong Kong. Although not all of such patients will attempt suicide or request euthanasia, some of them could not bear the suffering and no longer see meaning or value in life. If such existential distress is not carefully handled, the extended life expectancy would certainly impose further suffering on the advanced stage cancer patients. Therefore, resources should be allocated to the development of clinical interventions to address the existential distress of this group of patients so as to improve their existential wellbeing and reduce the possibility of premature death.

Meaning in life is a unique experience in different people. The current study aims to explore the effect of a brief, individualized, psychosocial intervention on the quality and meaning of life of advanced cancer patients.

Several studies showed that medically ill patients manifest a strong inverse relationship between spiritual wellbeing and existential concerns [4,5]. Cancer robs people of their hopes and dreams, not only threatening the physical body, but also the spirit. When confronted with a life-threatening disease like cancer, more existentialistic or self-centered issues become relevant to terminally ill patients [6-11]. Cancer patients tend to see cancer as a death sentence that threatens the meaning and purpose of their existence [12]. This belief may explain the higher incidence of suicide among people with cancer, especially at the terminal stage [13,14].

Unmet existential needs were faced by 25% to 51% of cancer patients [15]. Numerous studies [16-18] found that 13% to 29% of advanced cancer patients experienced moderate to severe existential distress, whereas approximately 25% experienced minor distress. In Morita et al. [17] study, 38% of terminally ill in-patients spontaneously expressed existential distress and 37% expressed meaninglessness in life. The Patients reported to receive desired help in overcoming fears, finding hope, talking about peace of mind, finding meaning in life and spiritual resources, as well as thinking about the meaning of life and death [15]. Approximately 40% of cancer patient subjects indicated their need for help in finding the meaning of life, and 70% of them needed someone to talk about the meaning of life [15].

Quality of life is often used as the primary outcome indicator for measuring the effect of care on advanced cancer patients. Generally, the measurement of QOL in healthcare is guided by two principles, namely, multidimensionality and subjectivity [19]. A number of previous studies have recommended that a comprehensive evaluation of QOL in palliative care should cover physical symptoms, physical, psychological, cognitive, social and sexual functioning, and body image [20].

However, a number of studies found this definition to be unduly restrictive in that it did not include existential concerns [21]. Indeed, increasing recognition of the importance of meaning of life is seen as one of the determinants of QOL, especially in palliative conditions [19]. Some advanced cancer patients reported good quality of life even though they faced inevitable death. Psychological adaptation may shift the focus of quality of life judgments from physical deterioration to social, psychological, and spiritual domains. Assessment and intervention to promote a greater sense of meaning might be very important for advanced cancer patients.

Sense of meaning has been associated with enhanced quality of life [22] and is specific to the terminally ill, resulting in less depression [5] and despair [23]. In studies of cancer patients, psychological adjustment to the disease is positively correlated with meaning in life [22,24].

Although palliative care clinicians are generally aware that dealing with dying patients’ existential suffering should be a priority, they recognize that the task is difficult [10]. Over the years, medical and psychological discourse on end-of-life care has steadily shifted from focusing primarily on symptom control and pain management to incorporating more person-centered approaches. Meaning making has become a central element of psychotherapeutic interventions [25,26]. Patients with limited life expectancy, whose meaning in life is sustained, are still able to consider their life as worth living [22,27]. At the same time, palliative nursing care personnel have to encounter questions about the meaning and values given to human existence [28]. That is, they have to recapture the meaning of life on behalf of those who are about to die soon.

In the acute oncology ward, advanced cancer patients may experience the deterioration of their own health and witness copatients’ death more frequently than patients in the general wards. This situation could be more stressful for the patients and their family members. Nurses have the privilege of having close contact with patients 24 hours a day during hospitalization. Hence, they are in a good position to offer individualized intervention through the process of daily nursing, and they can help patients live with dignity and meaning within a limited period. When a person is at the end of his or her life, it is important to give assistance in coping with psychological distress and existential concerns.

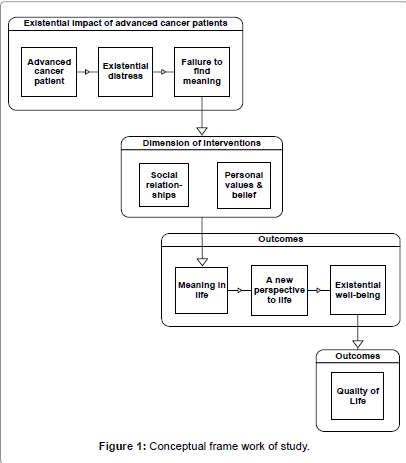

By searching positive meanings, advanced cancer patients may able to change their views about individual life, live more in the present, give new meaning to their experiences, and formulate a new perspective of life. Quality social relationships, health personal values and beliefs are important to enhance meaning in life and improve existential wellbeing and quality of life. Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of the present study.

The current study primarily addresses the following questions:

1. Does meaning-focused intervention affect the existential domain of advanced cancer patients as compared with those without using such interventions?

2. Does meaning-focused intervention affect the overall QOL of advanced cancer patients as compared with those without using such interventions?

3. What are the perceptions regarding the intervention among advanced cancer patients in the treatment group?

Methods

In this study, advanced cancer patients are defined as those suffering from incurable malignancy, clinical stage T3 and T4 disease at diagnosis, bone metastases [29] and highly fatal tumors, such as lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, squamous cell carcinoma [30], or patients expected to live less than six months with no existing established curative treatments.

Participants were recruited from the acute oncology wards of a public hospital in Hong Kong. Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the participants were screened by the nurses in charge of the respective wards.

Inclusion criteria

1. Age 18 or above

2. With advanced cancer disease

3. With clinical existential distress

4. Existential distress score of 1 or above, as determined by the QOL Concerns in the End of Life questionnaire (QOLC-E)

5. Expected to stay in the hospital for at least three days

6. Able to read or communicate in Chinese

Exclusion criteria

1. Age less than 18

2. Cognitive impairment

3. Too weak to communicate

4. Diagnosis of major depression or severe suicidal risk within the past six weeks

5. Enrollment in another clinical trial for which QOL is the primary end point

6. Change in antidepressant or psychotropic drug within six weeks of the study entry

7. Unable to read or communicate in Chinese

After screening by the ward nurses in charge, potential participants were approached by the investigator of the current study within the first two days of admission. They were briefed on the information contained in the consent form that they were asked to sign for the current study, which included details on the background of the current study, the right to refuse to participate in the study at any time during the study period, and further consent information for enquiries and complaints, both in verbal and written format.

This study employed a single blinded randomized controlled trial design with intervention and control groups, and measures taken at baseline, immediately after intervention, and two week after intervention. Quality-of-life concerns in the end of life questionnaire (QOLC-E) will be used as the measurement. There are 2 sessions for the intervention. Baseline measurement will be performed before the intervention. The intervention was based on logo therapy, a meaningcentered form of psychotherapy [31]. During the intervention, meaning was identified in terms of what participants gave to life (creative values), what they took from the world (experiential values), and the stand they took towards unavoidable predicaments (attitudinal values). Although the framework of the meaning was guided by Frankl’s theory, the facilitator did not claim to have an answer for the participant’s meaning of life, and the patients were autonomous and proactive in identifying individual sources that gave them creative, experiential and attitudinal values.

The first session involves a semi-structured interview that facilitates the search for meaning. It was guided by an interview manual and led by a facilitator who asked five core questions. The first question was “What do you think about your life?”, which aims to facilitate a review of significant life events (primary creative values). The second question, “How can belief help you face adversity?” aims to explore personal strengths, values, and belief as inner resources (primarily attitudinal values). The last three questions, “What do you do to love yourself and other?”, “What brings you joy?”, and “What do you appreciate in your life?” aim to facilitate a review of relationships and an exploration of the important things in life (Primarily experiential values). Each core question was followed by a series of probing questions, if needed.

The second session is to review, verify, and clarify the findings from the first session with the patients. The second and third measurement will be held one day and two weeks after the intervention for outcome measurements. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram of participants through each stage of the study.

The main focus of interest was in relieving existential distress and improvement of the quality of life. For this study, the quality of life is measured by the QOLC-E, which is a 28-item multi-dimensional instrument involving eight factors that emerged from the factor analysis and grouped into eight subscales: (1) support, (2) value of life, (3) foodrelated concerns, (4) healthcare concerns, (5) physical discomfort, (6) negative emotions, (7) sense of alienation, and (8) existential distress. The first four subscales measure the positive aspects of QOLC concerns, whereas the last four measures the negative aspects [32]. Few questions were negatively phrased, so a conversion of scores was conducted in a way that a higher score indicates a higher level of satisfaction.

Good internal consistency was reported, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 and a high percentage of variance (62.8%). The values are (1) physical discomfort subscale (4 items, alpha=0.77), (2) food-related concerns subscale (2 items, alpha=0.57), (3) negative emotions (4 items, alpha=0.87), (4) support subscale (2 items, alpha=0.64), (5) value of life subscale (6 items, alpha=0.83), (6) existential distress subscale (3 items, alpha=0.79), (7) healthcare concerns subscale (4 items, alpha=0.64), and (8) sense of alienation subscales ( 3 items, alpha=0.87) [32].

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Cluster Hospital of the involved hospital and the Human Subjects Ethics Subcommittee of the University and Research Ethics Committee. Documentation of informed consent had been provided and explained to each participant, and the consent forms signed first before the study commenced. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any stages without affecting their usual treatments and care.

Results

Statistical procedures were performed using the software SPSS version 17. A total 58 out of 84 subjects completed 2-week postintervention assessment. Among 84 participants, 45 (53.6%) were male and 39 (46.4%) were female. Their ages ranged from 38 to 91 years with a mean age of 64.02 ± 11.81 years. Demographic characteristics of the baseline measures are shown in Table 1.

| Intervention Group (n=44) | Control Group (n=40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 64.02 ± 12.37 | 65.28 ± 10.89 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male Female |

24 (54.5) 20 (45.5) |

21 (52.5) 19 (47.5) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| Illiterate Primary Secondary or above |

11 (25) 19 (43.2) 14 (31.8) |

8 (20) 18 (45) 14 (35) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||

| Non-married Married Widowed |

10 (22.7) 28 (63.6) 6 (13.6) |

2 (5) 31 (77.5) 7 (17.5) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| Nil Ancestor Worship Buddhism Christianity |

22 (50) 10 (22.7) 4 (9.1) 8 (18.2) |

18 (45) 7 (17.5) 9 (22.5) 6 (15) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Ca lung Colorectal cancer Ca breast Other cancer |

18 (40.9) 5 (11.4) 4 (9.1) 17 (38.6) |

14 (35) 12 (30) 4 (10) 10 (25) |

| Metastasis, n (%) | ||

| Single metastasis Multiple metastasis Nil |

25 (56.8) 16 (36.7) 3 (6.8) |

19 (47.5) 14 (35) 7 (17.5) |

| Span of time since diagnosis of cancer, mean ± SD | ||

| 57.00 ± 85.64 | 66.25 ± 98.67 | |

| Duration under palliative nursing care, mean ± SD | ||

| 3.57 ± 11.69 | 5.23 ± 19.33 | |

| Limitation of ADL, n (%) | ||

| Ambulant Walk with help Chair-bound Bed-bound |

16 (36.3) 9 (20.5) 9 (20.5) 10 (22.7) |

20 (50) 7 (17.5) 8 (20) 5 (12.5) |

| Agreed DNR, n (%) | ||

| Yes No Not mention |

16 (36.4) 0 (0) 28 (63.6) |

9 (22.5) 0 (0) 31 (77.5) |

| Current treatment, n (%) | ||

| Palliative Chemo Palliative RT Symptoms control Combined treatment |

5 (11.4) 16 (36.4) 19 (43.1) 4 (9.1) |

8 (20) 17 (42.5) 10 (25) 5 (12.5) |

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects.

A 3 (time of measurement) × 2 (condition) repeated measure ANOVA was used to assess changes in subscales of QOLC-E measures across all 3 time points, pre-treatment, post-treatment, and followup. Between-subject effects among various domains of QOLC-E were reported in Table 2. There was no significant difference in physical discomfort domain, food-related concern domain, negative emotion domain, sense of alienation domain, support domain, value in life domain, and health care concern domain of QOLC-E (all p>0.05). There was a statistically significant improvement in existential distress domain (F(1,81)=5.824, p=0.018), quality of life in single item (F(1,80)=4.919, p=0.029), and overall scales on average (F(1,81)=6.295, p=0.014) found for the intervention group compared to the control group.

| Dependent variable | Source | Type III Sum of squares | Df | Mean squares | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existential distress | Group Error |

55.056 765.745 |

1 81 |

55.056 9.454 |

5.824 | 0.018* |

| Quality of life in single item | Group Error |

22.322 363.023 |

1 80 |

22.322 4.538 |

4.919 | 0.029* |

| Overall scales in average | Group Error |

7.610 97.926 |

1 81 |

22.322 4.538 |

6.295 | 0.014* |

Table 2: Between-subjects effects among various domains of QOLC-E.

There were significant differences in negative emotion domain (F=7.467, p=0.003), supportive domain (F=6.292, p=0.004), value of life domain (F=6.665, p=0.003), existential distress domain (F=21.781, p<0.001), quality of life in single item (F=8.089, p=0.002), and overall scales in average (F=17.321, p<0.001) in the intervention group. Table 3 shows the results for Pairwise comparisons in the intervention group.

| Time of measure | Overall | To-T1 | To-T2 | T1-T2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig | F | Sig | F | Sig | F | Sig | |||||

| Physical discomfort | 0.842 | 0.420 | 1.189 | 0.282 |

0.994 | 0.324 | 0.009 | 0.924 | ||||

| Food-related concerns | 2.818 | 0.079 | 3.251 | 0.079 | 0.324 | 0.070 | 0.109 | 0.743 | ||||

| Negative emotion | 7.467 | 0.003** | 10.736 | 0.002** | 7.771 | 0.008** | 0.013 | 0.910 | ||||

| Sense of alienation | 3.089 | 0.055 | 4.828 | 4.828 | 0.008** | 0.070 | 0.49 | 0.826 | ||||

| Support | 6.292 | 0.004** | 8.110 | 0.007** | 8.267 | 0.006** | 0.303 | 0.585 | ||||

| Value of life | 6.292 | 0.004** | 8.073 | 0.007** | 8.620 | 0.005** | 0.001 | 0.977 | ||||

| Existential distress | 21.781 | <0.001** | 22.814 | <0.001** | 30.963 | <0.001** | 0.394 | 0.533 | ||||

| Health care concern | 2.952 | 0.064 | 4.702 | 0.036* | 3.024 | 0.009** | 0.114 | 0.737 | ||||

| QOL in single item | 8.089 | 0.002** | 10.355 | 0.002** | 8.759 | 0.005** | 0.028 | 0.868 | ||||

| Overall scales in average | 17.321 | <0.001** | 22.705 | <0.001** | 22.292 | <0.001** | 0.872 | 0.872 | ||||

Table 3: Pairwise comparisons in intervention group.

In this study, the support domain in both the intervention (F=6.292, p=0.004) and control (F=3.542, p=0.046) groups improved. As expected, there were no significant differences between groups (F=0.039, p=0.843). This shows the improved sense for being support or may not be related to meaning-focused intervention directly.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationships between the patients’ continuous demographic and clinical characteristics, and improvement of various domains of QOLC-E. Significantly weak to moderate correlations (r=0.226 to 0.635, p<0.001 to 0.038) were found among subscales.

Age (r=0.518, p<0.001), span of time since diagnosis (r=-0.315, p=0.038), and support (r=-0.358, p=0.017) were found to correlate significantly with the difference (T3-T1) of existential distress domain.

For the experimental group, an open-ended question was asked at 2 week after the intervention, to collect qualitative information on the usefulness of the intervention. Out of the 29 participants who were available to provide the data, 27 reported that they enjoyed the process of interviews and most (22, 75.87%) found it helpful. Two participants pointed out that not everyone was ready to talk about life and the process placed those with reservations under pressure. There was only one patient (3.44%) who commented that the interview sessions were ineffective because it offered nothing new for him, since he had come to terms with his situation using his own methods. Some of the participants (6, 20.69%) reported that they enjoyed the interview process, but it was difficult for them to determine whether the intervention was effective or not. A summary of the participants’ evaluation of intervention is shown in Table 4.

| Effectiveness | Reasons |

|---|---|

| Perceived as effective (22) | Increase sense of being concerned by health care professionals (6) Emotional needs addressed (6) Clarify life views and enhance self-understanding (5) Satisfy with the present situation (3) Improve family relationships (2) |

| Perceived as neutral (6) | No recollection of details (4) Physical fatigue (2) |

| Perceived as ineffective (1) | Nothing special for him (1) |

Table 4: Summary of participants’ evaluation of the intervention.

A total of 34 participants completed the intervention interview. The semi-structured interview guide focused on three main areas:

1. Facilitate a review of significant life events (primarily creative values) “What do you think about your life?”

2. Explore internal and external resources (primarily attitudinal values) “How have you faced adversities in life?”

3. Facilitate a review of relationships with the world (primarily experiential values) “What do you do to love yourself?”, “What brings you joy?” and “What do you appreciate in your life?”

During the interview process, self-defined meanings of the participants were categorized into two main categories: “personal values and beliefs” and “family and social relationship”. Key attributes of “personal values and beliefs” include courage to face challenges [14], show a grateful heart [10], accept reality and maintain hope [9], follow the natural path [9], enjoy simple life [5], and rely on higher power [2]. As for family and social relationship, it includes sense of connection with family and mutual support with others [32], and affirmation of worth [8].

Discussion

The finding of this study showed the brief, individualized meaningfocused intervention helps improve existential wellbeing and quality of life of advanced cancer patients.

The study indicates that the intervention may have a specific effect on improving the existential distress of advanced cancer patients given that there is a significant difference between the experimental group and the control group in the sub-scale of the QOLC-E-existential distress. Apparently, the intervention improved QOL, particularly by improving existential distress, which supports the theoretical notion that existential distress results primarily from the lack of meaning [31,33] and previous empirical findings that existential distress is alleviated by meaning-making [34]. However, Breitbart’s [34] study was conducted in groups, and the intervention consisted of eight sessions, whereas the current study was conducted on an individual basis and consisted of two sessions per subject. In addition, existential distress is defined differently by different authors. In the current study, existential distress was measured by three items: hopelessness, powerlessness, and helplessness. The intervention is a new attempt that focuses on meaning and quality of life and is effective for advanced cancer patients.

Apart from the existential domain of QOLC-E, the intervention affects quality of life in a single item (F=4.919, p=0.029) and in the overall scales of QOLC-E on average (F=6.295, p=0.014). Through the process of helping patients search for their own meaning, patients have a chance to express their own feelings and reframe them in a positive and meaningful way.

Although some studies on cancer patients have found that meaning-focused strategies, such as positive reframing, are related to better subsequent adjustment, such as improved quality of life and psychological wellbeing [35,36], others have reported that searching for meaning is related to poorer adjustment [37,38]. The results of this study show that a brief meaning-focused intervention effectively improves the level of existential wellbeing and quality of life of advanced cancer patients, especially in older people, patients who received inadequate palliative care services and who lack social support, and newly diagnosed patients in the advanced stage of illness. The findings are consistent with those of previous studies [12,39] for patients searching for meaning, as existential suffering is an essential coping strategy when meaning of the patients’ existence is threatened by suffering due to cancer.

Meaning is the cognizance of order, coherence, and purpose in one’s existence, the pursuit and attainment of worthwhile goals, and the accompanying sense of fulfillment [40]. Through the process of discovery and creation of individual meaning, a new perspective on the etiology and treatment of life problems can be found. Meaning-focused intervention empowers advanced cancer patients in overcoming even the most overwhelming circumstances of life, such as facing death and permanent separation of a beloved, and acts as a door leading to a unique human experience.

The common personal values and beliefs perceived meaningful by the participants in this study include the courage to face challenges, grateful attitude, acceptance of reality and maintenance of hope, following of the natural path, enjoying of a simple life, and relying on a higher power. Previous experiences in which they acknowledge themselves as responsible persons and previous job satisfaction also reinforce their efforts and contributions in the past.

Advanced cancer patients face the uncertainties of disease progression and the possibility of increased suffering in the future. This finding is also evident in De Faye et al. [16] study, with 59.6% of advanced cancer patients citing concerns about the future as their most significant source of existential distress. Positive thinking, reexamination of life, and religious and cultural beliefs are identified to be internal factors that facilitate their search for meaning and contribute to the process of growth [41]. Patients’ positive views on misfortune, family care, and sufficient social support are key elements of the healing process, as these alleviate psycho-spiritual suffering.

Several participants were unable to describe their underlying reasons for finding the intervention useful, simply stating that the process was helpful. In Chinese culture, discussing death is considered a social taboo; hence, they avoid broaching the topic. Palliative nurses should introduce the issue of death and improve a patient’s acceptance according to his/her pace. Addressing this concern and assisting patients in overcoming darkness in their lives can prepare them better in facing the challenge of uncertainty in the terminal stage of their lives and make the limited time spent with loved ones more meaningful. Family members and friends will feel more comfortable spending valuable time with their loved one as a result. This method is considered a subtle way of encouraging better coping by both patients and their relatives.

Although the initial results are promising, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the study results. It is possible that our study missed some patients who had a poor QOL but refused to participate. Extremely distressed patients should be given emotional support and clinical management, instead of being made to perform pre-assessment measures of research protocols. A second limitation of the study is its high attrition rate of 31% (26/84), a common characteristic of palliative care research. This study’s attrition rate is comparable to that of other palliative care studies [42]. The third limitation of this study stems from our sample having been solely obtained from an acute oncology setting within the same hospital. An opportunity to investigate the effectiveness of the intervention on other advanced illness in non-cancer and non-acute settings might uncover different aspects of the phenomena explored.

Conclusion

In summary, individuals with less support, lower quality of life, lack of palliative care, and old age seem to benefit more from meaningfocused intervention. Through the process of searching for meaning, advanced cancer patients can find their own meaning in life and are able to accept their current physical condition with better psychospiritual well-being, even in the terminal stages of illness. In this study, there was significant improvement in the negative emotion domain, support domain, value in life domain, existential distress domain, quality of life, and overall scale QOLC-E of the intervention group. The supportive domain among the participants was improved in both the intervention and control groups.

Creating meaning during the patients’ final journey was an integral part of patients’ healing process. Patients turned to internal resources, included suffering as a life challenge, and searched for life wisdom and external resources, including the support of family and peers, as they endured existential well-being. The study also found that younger patients are prone to receive more palliative care nursing services in the study hospital, and the level of physical discomfort and existential distress are significantly correlated.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to Prof. Esther Mok of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for her marvelous coaching and expert advice; Dr. C. C. Yau, Chief of Services, and Mr. C. K. Lo, Department Operation Manager. Both of them are in the Oncology department of Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong, without their consent and enthusiastic support, this research project could not have been implemented and completed. I also thank all the patients, who participated in this study, and shared their experiences generously, and all staff of the department of Oncology of Princess Margaret Hospital for their assistance in the recruitment.

This study was financially supported by the General Research Fund of the HKSAR Government University Grants Committee (Project number: 562109). There are no potential conflicts of interest for me.

References

- Department of Health, HKSAR (2011) Number of deaths by leading causes of death, 2001-2010. Centre for Health Protection.

- Meraviglia MG (2004) The effects of spirituality on well-being of people with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 31: 89-94.

- Ho TP, Tay MS (2004) Suicides in general hospitals in Hong Kong: retrospective study. Hong Kong Med J 10: 319-324.

- Fehring RJ, Miller JF, Shaw C (1997) Spiritual well-being, religiosity, hope, depression, and other mood states in elderly people coping with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 24: 663-671.

- Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Galietta M (2002) Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 43: 213-220.

- Bolmsjö I (2000) Existential issues in palliative care--interviews with cancer patients. J Palliat Care 16: 20-24.

- Farber SJ, Egnew TR, Herman-Bertsch JL, Taylor TR, Guldin GE (2003) Issues in end-of-life care: patient, caregiver, and clinician perceptions. J Palliat Med 6: 19-31.

- Grumann MM, Spiegel D (2003) Living in the face of death: interviews with 12 terminally ill women on home hospice care. Palliat Support Care 1: 23-32.

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton TF (2004) Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 18: 39-45.

- Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Hatzipli I, Smyrnioti M, et al. (2008) Demographic and clinical predictors of spirituality in advanced cancer patients: a randomized control study. J Clin Nurs 17: 1779-1785.

- Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Friedlander-Klar H, et al. (1994). The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer 30A: 1326-1336.

- Chio CC, Shih FJ, Chiou JF, Lin HW, Hsiao FH, et al. (2008) The lived experiences of spiritual suffering and the healing process among Taiwanese patients with terminal cancer. J Clin Nurs 17: 735-743.

- Miller M, Mogun H, Azrael D, Hempstead K, Solomon DH (2008) Cancer and the risk of suicide in older Americans. J Clin Oncol 26: 4720-4724.

- Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, Redman M, Yueh B (2008) Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 4731-4738.

- Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, Grennan J, Carter J, et al. (1999) Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psychooncology 8: 378-385.

- De Faye BJ, Wilson KG, Chater S, Viola RA, Hall P (2006) Stress and coping with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care 4: 239-249.

- Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S (2000) An exploratory factor analysis of existential suffering in Japanese terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 9: 164-168.

- Pelletier G, Verhoef MJ, Khatri N, Hagen N (2002) Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. J Neurooncol 57: 41-49.

- O'Boyle CA, Waldron D (1997) Quality of life issues in palliative medicine. J Neurol 244: S18-S25.

- Cella DF (1992) Quality of life: the concept. J Palliat Care 8: 8-13.

- O’Boyle CA (1996) Quality of life in palliative care. In: Ford G, Lewin I (1996) Managing terminal illness. London: Royal College of Physicians.

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D (1999) A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 8: 417-428.

- McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W (2003) Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 361: 1603-1607.

- Taylor EJ (1993) Factors associated with meaning in life among people with recurrent cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 20: 1399-1407.

- Breitbart W, Heller K S (2003) Reframing hope: meaning-centered for patients near the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine 6: 979-988.

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, et al. (2005) Understanding the will to live in patients nearing death. Psychosomatics 46: 7-10.

- Ryff C, Singer B (1998) The role of purpose in life and personal growth in positive human health. In: Wong P, Fry P (1998) The human quest for meaning. A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications. Mahwah N J Lawrence Erlbaurm Associates.

- Pipe TB, Kelly A, LeBrun G, Schmidt D, Atherton P, et al. (2008) A prospective descriptive study exploring hope, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in hospitalized patients. Medsurg Nurs 17: 247-257.

- Schellhammer PF, Pienta KJ (2000) Therapy for advanced and hormone refractory cancer of the prostate. Clinical Urology 26: 256-269

- Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, McPherson CJ, LeMay K, Allard P, et al. (2007) Suffering with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 25:1691-1697

- http://jco.ascopubs.org/content/25/13/1691.abstract

- Frankl VE (1959) Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press, Boston.

- Pang SM, Chan KS, Chung BP, Lau KS, Leung EM, et al. (2005) Assessing quality of life of patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the end of life. J Palliat Care 21: 180-187.

- Murata H, Morita T, Japanese Task Force (2006) Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japanese Task Force: the first step of a nationwide project. Palliat Support Care 4: 279-285.

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, Pessin H, Poppito S, et al. (2010) Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology 19: 21-28

- Dirksen SR (1995) Search for meaning in long-term cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs 21: 628-633.

- Roesch SC, Adams L, Hines A, Palmores A, Vyas P, et al (2005) Coping with prostate cancer: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med 28: 281-293.

- Roberts KJ, Lepore SJ, Helgeson V (2006) Social-cognitive correlates of adjustment to prostate cancer. Psychooncology 15: 183-192.

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Huggins ME (2002) The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: Hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psychooncology 11: 93-102.

- Narayanasamy A (2002) Spiritual coping mechanisms in chronically ill patients. Br J Nurs 11: 1461-1470.

- Wong PTP (1988) Aging as an individual process: Toward a theory of personal meaning. Springer, New York.

- Tang VYH, Lee AM, Chan CLW, Leung PPY, Sham JST, et al. (2007) Disorientation and Reconstruction: The meaning searching pathways of patients with colorectal cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 25: 77-102.

- Palmer JL (2004) Analysis of missing data in palliative care studies. J Pain Symptom Manage 28: 612-618.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16235

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2012 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11687

- PDF downloads : 4548