Research Article Open Access

Healthy Girls and Healthy Communities: Two Sides of the Same Coin?

Lisa M Vaughn1*, Sara Drabik2, and Alexandra Kissling3

1Professor, Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine/Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, USA

2Assistant Professor, Department of Communication, College of Informatics, Northern Kentucky University, USA

3Research Assistant, Emergency Medicine, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Lisa M Vaughn

Professor, Department of Pediatrics

College of Medicine/ Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

University of Cincinnati, USA

Tel: 513-636-9424

Fax: 513-636-1695

E-mail: lisa.vaughn@cchmc.org

Received date: February 11, 2014; Accepted date: March 10, 2014; Published date: March 13, 2014

Citation: Vaughn LM, Drabik S, Kissling A (2014) Healthy Girls and Healthy Communities: Two Sides of the Same Coin? J Community Med Health Educ 4:279. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000279

Copyright: © 2014 Vaughn LM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

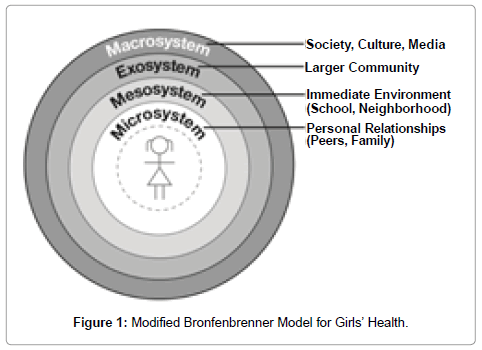

Lacking is research on girls’ health particularly within the context of the community and larger societal influences. The purpose of this study was to explore the knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes of girls and community residents about what makes a girl healthy and what places girls’ health at risk. Sixty-six adolescent girls and boys, their parents, senior citizens, educators, and community leaders in business, government, safety and health participated in group interviews. Interviews were coded and analyzed using a standard qualitative approach based on grounded theory and constant comparative method. Two primary themes emerged from the interviews: 1) a complete and holistic view of girls’ health that includes physical, mental, and emotional health; and 2) the importance of girls having positive role models and strong supportive relationships. The two primary themes led us to propose a modified version of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological systems model adapted to girls’ health. Our proposed model emphasizes how context and the whole system influence and informs girls’ health and wellness. Girls are in the center interacting with and influenced by peers, family, school, community, and the media. Our adapted Bronfenbrenner model provides an opportunity for health care providers and policy makers to examine the levels at which girls’ health can be influenced and enhanced.

Keywords

Girls’ health; Social ecological model; Community health; Self-in-relation theory; Bronfenbrenner’s model

Introduction

Being a healthy girl in our complex, multifaceted, rapidly changing world is at best challenging, ambiguous and contradictory. Amidst more traditional health concerns such as medical problems, nutrition, body image and hygiene, girls must also struggle with broader aspects of health and well-being including what and who is important, negotiating relationships, having “voice,” operating within sometimes unhealthy and unsafe neighborhoods and communities, handling media-saturated and paradoxical messages about sexuality and what it means to be a girl, and managing gendered expectations of who they are and can become. Current research on girls’ health accentuates their risk behavior and deficits [1-4]. Needed is a model of girls’ health and well-being that is socially embedded and considers the relational and environmental contexts [5] in conjunction with more traditional concerns. Such a viewpoint will allow for a focused understanding of health education and intervention strategies that are directly applicable to the entirety of a girl including where she lives, plays and goes to school and will improve the potential for sustainable change.

According to social ecological theory, an individual’s health is influenced by the dynamic interplay between personal characteristics, including genetics, behavioral patterns, and mental states, and environmental circumstances, including everything from economic policies to neighborhood characteristics [6,7]. Bronfenbrenner more specifically delineates the nested systems that have direct and indirect influences on child health and the influence of the interactions between systems [8,9]. His model includes four different ‘layers’ of environment. Societal and cultural influences, values, and traditions lie on the outermost sphere (the Macrosystem), depicting the largest and most remote level of influence on an individual. Moving inward, the next layer is the Exosystem, which includes environments that the child does not experience directly, such as a parent’s workplace, but that nonetheless have an indirect effect on the child’s development. The next layer is the Mesosystem, which includes the connections to immediate environments (e.g., neighborhood, school). The innermost layer is the Microsystem which is an individual’s immediate environment including relationships and interactions (e.g., family, peers).

Social ecological systems approaches like Bronfenbrenner’s posit that every layer of the system is important and those individuals, in this case girls, do not exist in a vacuum. Girls are both influenced by and connected to multiple people and factors all of which affect girls’ development and health. While the girls are at the center and directly affected by parents and peers, all layers of the system surround and have an influence on the girl. When a girl leaves adolescence with unhealthy behaviors, she is likely to deal with the same issues in adulthood [5,10]. If we can affect girls’ health in a positive way, we have the possibility of not only preparing girls for healthy, empowered and productive adulthood but also for “the payoffs that will accrue to girls and to their families, communities, and countries over many generations” [11 p.1]. In this study, we explore the knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes of girls and community residents about what makes a girl healthy and what places girls’ health at risk. Through this exploration, we derived a modified version of Bronfenbrenner’s model adapted to girls’ health.

Methods

This study was based on video and audio-taped group interviews conducted as part of a larger service-learning project. The project was created to provide a snapshot of girls’ health from the perspective of girls themselves and relevant community members and raise awareness about the barriers to girls’ health in local communities. The larger project resulted in a final condensed video summarizing all the group interviews, a community report, curriculum and toolkit that other organizations could use to collaboratively build programs and initiatives to support girls in their communities. As part of the larger project, we conducted in-depth, qualitative group interviews with girls and a variety of community members from two communities in the Greater Cincinnati area. Interviews were videotaped to create a more direct connection between the viewer and the subjects, allowing them authority and ownership by speaking in their own voice [12,13]. The videos of the interviews are being analyzed as cultural artifacts and are accessible via password on the Healthy Girls project website (healthycommunitieshealthygirls.com).

Setting

Two greater Cincinnati neighborhoods were selected for this project because of previous partnerships with community agencies within them and because of their designation as two of the United Way Place Matters communities [14]. Neighborhoods designated as such struggle with significant social and economic challenges.

Participants

A total of 66 participants were recruited using a snowball sampling technique whereby girls and community members recommended other people who might want to participate in the study. Sixteen group interviews composed of 2-6 individuals were conducted based on primary roles/characteristics (e.g., teachers, business owners, religious leaders, girls, etc.). The participating girls represented the diversity of their communities and ranged in age, race/ethnicity, and family structure. The participating community members represented various agencies and community organizations including schools, churches, public safety, government, and health centers. Food and snacks were offered at the group interviews but no incentives were given. Participants signed a video release consenting to filmed interviews and to have these videos shared with the public via community screenings and the internet. Participants were invited to three different private screenings of the final video before public showings occurred and received the opportunity to remove their comments from any portion of the film. This feedback was solicited publically and anonymously from those in attendance. No participants requested their comments be removed. Some participants did not attend the screenings.

Measures/data collection

Group interviews occurred at a variety of community sites conveniently located for participants. Interviewers; (university students trained in group interview techniques) used interview guides with questions about girls’ health and the role of the community in it. Specific follow-up questions were asked of each group based on their particular role within the community. Before the interview began, interviewers explained that for the purposes of this project, participants should focus on girls in junior high and high school (approximately ages 10-18); consider community to include their neighborhoods, schools, businesses, health centers, and churches; and think of health broadly to include physical, mental, and social well-being. The interviews were videotaped, transcribed verbatim using both audio and video to ensure correct transcription, and reviewed by the interviewers for accuracy.

Data analysis

In order to allow for the voices of the girls and community members to emerge in the data, we used a modified grounded theory approach to inductive coding. Specifically, the research team independently reviewed line-by-line seven randomly selected transcripts of the group interviews and assigned codes as they became apparent [15]. We highlighted lines and sections of the text to help demonstrate and develop broad conceptual categories. When inconsistencies and discrepancies in the coding occurred, the researchers discussed until 100% agreement was reached about which themes were represented. As categories, themes, and linkages were explicated, we identified and condensed unifying themes into a manageable number of broad categories [15]. Next, based on the agreed upon categories, each member of the research team coded three interviews to complete the remaining nine interviews. Following the grounded theory approach, the research team conducted multiple readings of the interviews to extract the main themes, phrases, stories, and meanings of the responses as they related to girls health and well-being. This process allowed the categories to emerge rather than imposing preconceived categories or models and the words of the participants to become the priority. Through constant comparison and discussion among research team members, the code structure evolved inductively, reflecting “the ground” or the actual lived experiences of the participants [16]. To ensure credibility of the qualitative analysis, we used both peer checking and member checking to verify the accuracy of the themes and gaps in the data [17]. Specifically, as the research team was engaged in identifying codes, we conducted peer checking by discussing emerging findings with our larger research lab group who provided suggestions and scrutinized the findings. Further, multiple meetings were held with partnering agencies and participants to discuss content and compile the final video as a form of member checking the salient themes.

Findings

Two primary themes emerged from the interviews: 1) a complete and holistic view of girls’ health that includes physical, mental, and emotional health; and 2) the importance of girls having positive role models and strong supportive relationships.

The first theme was the importance of a complete and holistic view of health. All the interviewees asserted that being a healthy girl is about more than just physical health. “What comes to mind when I think of a healthy girl (she has a solid foundation, and good support in her life. Not only being in good physical health... but one who has a positive image of herself,” said a community safety official. Different groups emphasized a facet of health that was most important to them, but the overall consensus across girls and community members was that being healthy in all areas, both physical and mental, was the best. The girls themselves tended to emphasize being “happy in yourself” and keeping your body active. One girl said that being healthy means “exercising, eating vegetables, and keeping in shape.” Other community members placed more emphasis on overall mental and social well-being. A young boy commented, “I think to be healthy means to feel comfortable about yourself and being able to do what you think you can do.”

Participants in this study described that an unhealthy girl is also more than just physically unhealthy, though they differed on what exactly makes a girl unhealthy. The girls tended to emphasize poor eating habits and having a negative attitude as being unhealthy. One girl described an unhealthy girl as “someone that starts a lot of drama that feeds off of negativity.” Community members defined an unhealthy girl more through the causes of her being unhealthy rather than the symptoms. They noted that she lacked role models, had no support system, and had no assistance from her community.

The second theme was the importance of role models and developing close, personal relationships with others. Participants saw a healthy girl as a positive role model to other girls, and one who has role models of her own. Community members saw the lack of good role models as a clear cause of poor health among girls. One business leader noted “I think both healthy and unhealthy girls are dependent on their role models and where they’re getting their information from.” Community members saw the need for girls to develop relationships with adult members throughout the community. A non-profit leader noted “the community plays a role in engaging the young girls in work and in the community, whether that’s litter pick-ups or safety initiatives or arts programming. I think young women need to know that they’re part of something bigger.” When asked about when and why unhealthy lifestyles start, both girls and community members described that unhealthy behaviors start at home. As one parent noted, “kids emulate what they see.” A government official summed up the thoughts of many participants regarding the lack of role models for girls: “We have so many young women who are left on their own without any real guidance from anyone. It’s not necessarily that parents don’t want to be there as a positive role model, but rather they have to work in order to financially support them.” A non-profit leader emphasized the interconnectedness of everyone in the community and that raising healthy girls “really does take a village.” While many saw that the parents were the first and most important role models for a young girl, they also recognized that due to a variety of social and environmental factors, the parents could not always be counted on to provide this connection. “We need each other to raise these kids, to raise these young women. We all need to do it together.” The girls agreed on the crucial role that positive role models play in their lives. They said that good role models could help them develop goals and ensure healthy development.

The two primary themes led us to propose a modified version of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological systems model [8] adapted to girls’ health. Our proposed model emphasizes how context and the whole system influences girls’ health and wellness (Figure 1). We present the model by delineating each of the interconnected layers as described by the participants: girls themselves, friends and peers, parents and family, school, community, and media.

Girls themselves are in the center of the model interacting with and influenced by their peers, family, school, community, and the media. Community members and girls themselves clearly understood that self-perception and self-worth are of high importance when it comes to a girl’s general health. One business leader saw a healthy girl as knowing herself with self-confidence and self-esteem. The girls who were interviewed realized that it was extremely important to take care of and appreciate yourself.

The next level outside the girl is her friends and peers. Girls realized that to be healthy, you need to “surround yourself with people that are gonna benefit yourself and….your future.” The girls said that sometimes parents aren’t available and girls might not feel comfortable talking to other adults, so girls in the interviews recommended that listening to their peers was important. When asked where they would go to talk to someone about health, one girl replied, “I think the first thing I would ever do is go to my friends”. Another girl said: “I go to my friends. Even though they are my age, we all go through different experiences and go through different stages at different times…, I can go and confide in them.”

The next layer of influence in the model, parents and family, was largely regarded by both community members and girls as the most important level of support for girls’ health and well-being. Family was viewed as the “first line of defense” to healthy girls. Both community members and girls described that mothers are the primary role models to girls. Participants felt that if a mother has unhealthy habits, or is not present in the lives of her daughters, she is likely to perpetuate the cycle of unhealthy habits. Most participants believed that the home environment is where good or bad habits start. As one parent explained, “it starts at home with the role models that kids have early on.” A non-profit leader remarked, “Healthy girls become healthy moms, and that’s such an important link, in teens of the future and where the young ladies are going.” A government official noted that, “If we have unhealthy children growing up to be unhealthy adults, having even unhealthier children, then we’re going to contribute to have more and more problems that we are not going to be able to resolve.”

School provides the next level of support for girls’ health. Both community members and girls mentioned the potential of school to have a positive effect on girls’ health and well-being. In the interviews, there was an outcry for after-school activities, particularly sports. One girl noted, “I think we need more programs, because there’s too much free time around here for kids.” The importance of teachers and their involvement in girls’ lives was also noted, especially by the girls. Some girls said they were open to talking to teachers or counselors-“You can have several conversations with them just like they’re your friends” and “They are really approachable…. they will always take care of you and be there for you no matter what.” Other girls noted that they did not feel comfortable talking to teachers or counselors because they were not approachable. Community members described that schools can influence girls by: “…helping them make choices and giving them opportunities to be leaders and to shine in their academics and classrooms…all of that helps them to develop that self-esteem and that courage that they need.”

The next level of support in girls’ health is the community. For the purposes of this project a community was defined by the physical space, or the neighborhood in which you reside and/or spend time. Although community members and girls alike recognized the importance of community responsibility in girls’ health, a significant problem identified was that people lacked the motivation to become involved in their community in general and specifically with young girls’ health and well-being. One business leader noted, “It’s easy to overlook the importance of young girls’ health because it’s not in front of us…most communities simply are not aware of what’s going on in the youth. Without the involvement of community members a girl’s health can suffer.” A safety official noted that, “It’s the responsibility of everyone in the community to make an effort to improve her life and, as a result, improve their community. And that includes police educators, fire officials, social workers or anybody.”

Another significant problem noted within the community sphere was that of safety particularly with regard to neighborhood environment. A community safety official said, “I think community safety is related to girls’ health-- if girls feel safe, they are out there with their friends, their peers…in a healthy atmosphere.” One girl commented, “The bad outweighs the good down here. They got kids selling drugs, little girls prostituting themselves on the corner down here and that ain’t right.” Another girl said “All the streets are really dirty and you wanna go outside and play in your yard or something but you can’t cause there’s so much trash and broken glass.”

The final level of our model is the media. Both the girls and the community members acknowledged that the media was highly influential on girls’ health. “I think the media plays a huge role in the health of a girl. In both healthy ways and unhealthy ways,” said one parent. In the interviews, no one felt that the media was doing a good job of influencing young women in a positive way, but girls saw media as less damaging. Community members described a saturated media for girls—one with negative images about female bodies and sexuality. While some participants were able to find some examples of women providing a positive example in the media, overall they felt that the media was there to sell them a product. Parents noted that even when the media emphasizes health, they talk about the commodities you need to buy for your children so they can be healthy.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore what makes a girl healthy and what places girls’ health at risk from the perspectives of girls and community residents. Overall, girls and community members agreed that healthy girls encompass physical, mental and social health. This perception of health mirrors the 1948 World Health Organization definition that suggests that health is more than just an absence of disease or infirmity and involves a combination of physical, mental and social well-being [18].

Girls and community members also agreed that it is important for girls to have positive role models and strong supportive relationships. This is not surprising given the premise of self-in-relation theory which explains that relationships are important to adolescent development as a whole, but particularly to young women's development [19]. Supportive teachers, counselors, or other adults have been shown to have positive effects on adolescent health such as enhanced well-being [20], improved social acceptance, body image, and avoidance of future drug use [21], prevention of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections [22].

The two emerging themes from the interviews and our proposed model for girls’ health, a modified version of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological systems model, suggest that each level of the system influences and informs girls’ health and well-being. Girls are at the center of the model. In the current study, the girls and even the boys emphasized that to be healthy, girls need to feel comfortable and happy with themselves. Individual factors like self-esteem and self-worth have been associated with general health, physical activity and healthy eating [23]. Self-esteem is an essential core of girl’s health, yet research consistently shows that girls have lower self-esteem than boys and that it decreases throughout adolescence [24,25]. Girls in general are aware of the multitude of extra pressures placed on them, from emotional to development challenges [24,26] yet they still often do not recognize their strengths and personal value [27] or maintain their own “voice” or right to self-expression [28].

The next layer of the model, friends and peers, can be a major influence on girls when it comes to healthy or unhealthy behaviors. Overall, girls’ experience of self is relational, and girls/women develop a sense of self through the context of important relationships [19]. Research has shown that positive peer relationships are crucial to healthy girls in terms of their self-worth and life satisfaction [29] and are a key index of a child’s social competence and emotional well-being [30]. Further, connections with prosocial peers can serve to protect adolescents from a wide range of health risk behaviors including violence, substance misuse and sexual risk [31].

Parents and family, the next layer in the model, are an essential component of girls’ health and well-being. Research has indicated that girls with lower familial or social support demonstrate more risky behavior as they enter adulthood [32]. Parents play a crucial role in promoting health and wellness for girls [33] and family connectedness has been posited as one of the most important protective factors for adolescents [31]. Adolescents who are connected to their family are more likely to have positive health outcomes including delayed sexual initiation, lower levels of reported cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use, and less involvement in violent activities [31].

The next layer of influence in the model is school. School and its associated pressures and worries can in fact be one of the biggest stressors in an adolescent’s life [34]. Teachers can be positive role models for girls and impact learning, success in school and overall health and well-being [34,35]. In fact, programs that improve school environment and connectedness show promise in terms of improving health outcomes in adolescents [31].

Community is the next level of support in the model. Girls and community members mentioned the importance of a safe community for girls’ health. Those that live in social disadvantage may be particularly prone to multiple and interrelated stressors in their neighborhoods including violence, drug activity, poor mental health, teenage pregnancy, litter, poor housing and fear of or actual sexual harassment, all of which contribute negatively to positive growth and development [31,35].

Finally, media is the outermost level of the model. Community members described media as being a negative influence on girls’ health especially regarding body image and sexuality. The research literature has consistently linked media with the pressure for a thin, idealistic body image, body dissatisfaction and disturbed eating in girls as young as seven years old [36,37]. The cumulative effect of repeated exposure to such media messages can lead to girls to believe that media portrayals are representative of reality [38,39]. Media aimed at young girls has increasingly become not just about selling a false reality, but about selling the products to “achieve” this reality, resulting in the equating of femininity and empowerment with consumption itself [40].

Limitations

Although this study extends understanding of girls’ health within a community context, potential biases may have arisen in our data collection and analyses. With regard to data collection, the group interview method can pose some limitations related to interviewer emphasis on certain questions or interviewees’ comfort with certain questions. Since the data for the study were self-reported and videorecorded in a group setting, participants may have felt the need to either provide socially acceptable answers or censor certain thoughts and feelings. However, the structured interview guide was designed to target particular areas yet be broad enough to allow for maximum variation in responses. In terms of data analyses, the grounded theory approach requires that researchers remain neutral and unbiased with regard to the emerging findings [16]. Because the authors are positioned in academic institutions, we were informed about the extant research literature on girls’ health before we started the study. However, during analysis of the interviews, we remained “grounded” in the words of the participants throughout multiple levels of coding and inductively arrived at our proposed model for girls’ health only after peer checking and member checking had occurred and we had begun writing the manuscript. Further, given the nature of this qualitative study with small numbers of participants limited to two neighborhoods in a particular city, caution should be exercised in the generalizability of our results to other girls and communities.

Conclusion

We qualitatively explored girls health from both the girls’ and their communities’ perspectives. Our suggestion that girls’ health be approached from a social-ecological systems perspective (i.e., the modified Bronfenbrenner model) was supported by the interviews. Much of the extant literature on girls’ health has a tendency to blame the girls themselves rather than casting a wider lens that looks to the people and environment surrounding girls (see for example Donenberg et al.), and it concentrates primarily on vulnerability to negative health outcomes such as pregnancy or sexually transmitted infections, expert professional viewpoints rather than from the girls themselves, individual aspects of health versus community level contributions to girls’ health, and/or a singular aspect of health (e.g., physical health, mental health) [5,31,41]. Our new model provides an opportunity to examine the levels at which girls’ health can be influenced and enhanced. If programs and interventions addressing girls’ health are to be effective, all layers of the social-ecological system have to be targeted [6,42]. As indicated by our findings, healthy girls and healthy communities do appear to represent two sides of the same coin. Without healthy peers, parents/families, schools, neighborhoods, and societal influences like media, we are unlikely to find healthy girls. We must be cognizant that “young people grow to adulthood within a complex web of family, peer, community, societal, and cultural influences that affect present and future health and wellbeing” [31 p.1641].

Further study is especially pertinent in the arena of girl’s health. Future research needs to include girls from varied backgrounds and communities to enhance the depth and scope of knowledge about the relationship between girls’ health and their communities. Health and social service practitioners have substantial opportunity to advocate for girls by understanding the context and community in which girls live and by designing effective resources for girls’ health that address various levels of the system.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Judith Harmony for helping to align the community partners and recruiting program participants, Lisa Mills and Kathy Burklow for their leadership in developing the program, and to funding support from The Greater Cincinnati Foundation, The Women’s Fund, Local Initiatives Support Corporation of Greater Cincinnati, the Kroger Company, Scripps Howard Center for Civic Engagement and Learn and Serve America.

References

- Assadi M, Zerafati G,Dham BS, Contreras L, Akbar U, et al (2012).The prevalence, burden and cognizance of migraine in adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatric Neurology:29-34.

- Donenberg GR, Emerson E, Mackesy-Amiti ME (2011) Sexual risk among African American girls: psychopathology and mother-daughter relationships. J Consult ClinPsychol 79: 153-158.

- Groth SW, Morrison-Beedy D (2011) Smoking, substance use, and mental health correlates in urban adolescent girls. J Community Health 36: 552-558.

- Meyer KA, Friend S, Hannan PJ, Himes JH, Demerath EW, et al. (2011) Ethnic variation in body composition assessment in a sample of adolescent girls. Int J PediatrObes 6: 481-490.

- Cooper SM, Guthrie B (2007) Ecological influences on health-promoting and health-compromising behaviors: a socially embedded approach to urban African American girls' health. Fam Community Health 30: 29-41.

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen A, et al (2003) Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 53-76.

- Stokols D (1996) Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot 10: 282-298.

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977)Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American psychologist:513.

- Bronfenbrenne U (2005) Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005.

- Smith Adock S, Webster SM, Leonard LG, Walker JL (2008) Benefits of a holistic group counseling model to promote wellness for girls at risk for delinquency: An exploratory study. Journal of Humanistic Counseling Education and Development:111-126.

- Temin M, Levine R, Stonesifer S (2009) Start with a girl: a new agenda for global health. Issues in Science and Technology:33-40.

- Chapman J (2009) Issues in Contemporary Documentary. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Nichols B (2010) Introduction to Documentary (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- United Way of Greater Cincinnati. place matters (2012) Helping Neighbors Help Themselves 2012

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ (2007) Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 42: 1758-1772.

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967).The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research: Aldine de Gruyter

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization

- Jordan JV, Kaplan AG, Miller JB, Stiver IP, Surrey JL (1991) Women's growth in connection: Writings from the Stone Center: Guilford Press.

- Po Sen CHU, Saucier DA, Hafner E (2010) Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support nd well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology:624-645.

- Kuperminc GP, Thomason J, DiMeo M, Broomfield-Massey K (2011) Cool Girls, Inc.: promoting the positive development of urban preadolescent and early adolescent girls. J Prim Prev 32: 171-183.

- Gavin LE, Catalano RF, David-Ferdon C, Gloppen KM, Markham CM (2010) A review of positive youth development programs that promote adolescent sexual and reproductive health. J Adolesc Health 46: S75-91.

- Hargreaves DS, McVey D, Nairn A, Viner RM (2013) Relative importance of individual and social factors in improving adolescent health. Perspect Public Health 133: 122-131.

- LeCroy CW (2005) Building an effective primary prevention program for adolescent girls: Empirically based design and evaluation. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 5:75-84.

- Benson PL (2006)All kids are our kids: What communities must do to raise caring and responsible children and adolescents: Jossey-Bass.

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P, Reid JB (2005) Intervention outcomes for girls referred from juvenile justice: effects on delinquency. J Consult ClinPsychol 73: 1181-1185.

- Carlock C (1999) Enhancing self-esteem. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Hirsch BJ, Roffman JG, Deutsch NL, Flynn CA, Loder TL, et al. (2000) Inner-City Youth Development Organizations: Strengthening Programs for Adolescent Girls. J Early Adolesc 20: 210-230.

- Ma CQ, Huebner ES (2008) Attachment relationships and adolescents' life satisfaction: Some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychology in the Schools:177-190.

- Ladd GW(2006) Children's peer relations and social competence: a century of progress. current perspectives in psychology. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, et al. (2012) Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 379: 1641-1652.

- O'Donnell L, Myint-U A, Duran R, Stueve A (2010) Especially for Daughters: Parent Education to Address Alcohol and Sex-Related Risk Taking Among Urban Young Adolescent Girls. Health Promotion Practice:70S-78S.

- Trask-Tate A, Cunningham M, Lang-DeGrange L (2010) The Importance of Family: The Impact of Social Support on Symptoms of Psychological Distress in African American Girls. Research in Human Development:164-182.

- LaRue DE, Herrman JW (2008) Adolescent stress through the eyes of high-risk teens. PediatrNurs 34: 375-380.

- Chandra A, Batada A (2006) Exploring stress and coping among urban African American adolescents: the Shifting the Lens study. Prev Chronic Dis 3: A40.

- Dohnt HK, Tiggemann M (2006) Body image concerns in young girls: The role of peers and media prior to adolescence. Journal of youth and adolescence:135-145.

- Grabe S, Hyde JS (2006) Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction amo ng women in the United States: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 132: 622-640.

- Brown JD, Witherspoon EM (2002) The mass media and American adolescents' health. J Adolesc Health 31: 153-170.

- Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS (2008) The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull 134: 460-476.

- Johnson NR (2010) Consuming desires: Consumption, romance, and sexuality in best-selling teen romance novels. Women's Studies in Communication:54-73.

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, et al. (2012) Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet 379: 1630-1640.

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB (2008) Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons:465-486.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15611

- [From(publication date):

March-2014 - Sep 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10985

- PDF downloads : 4626