Research Article Open Access

Growing Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases in the Developing Countries: Is there a Role for Small Dense LDL Particles as an Inclusion Criteria for Individuals at Risk for the Metabolic Syndrome?

Anjali Arora1, Qamar A Khan2, Vrinda Arora3, Nitika Setia3 and Bobby V Khan2*

1Hyperlipidemia Prevention Clinic, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

2Atlanta Vascular Research Foundation, Saint Joseph’s Translational Research Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

3Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Center for Medical Genetics, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Bobby V Khan

Atlanta Vascular Research Foundation

5673 Peachtree Dunwoody Road, Suite 440

Atlanta, Georgia 30342, USA

E-mail: bobby.khan@atlantaclinicalresearch.com

Received date: May 20, 2013; Accepted date: October 08, 2013; Published date: October 10, 2013

Citation: Arora A, Khan QA, Arora V, Setia N, Khan BV (2013) Growing Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases in the Developing Countries: Is there a Role for Small Dense LDL Particles as an Inclusion Criteria for Individuals at Risk for the Metabolic Syndrome? J Community Med Health Educ 3:243. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000243

Copyright: © 2013 Arora A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome is significant in nations with developed economies and is growing in countries with rapidly growing economies. The reasons for this are complex but include increased availability to cheaper (and less nutritious) food and increased mechanization. This results in reduced physical activity and an increase in total body fat and weight. Current inclusion criteria for the metabolic syndrome include parameters of obesity, elevated blood glucose, elevated triglycerides, and low HDL cholesterol. However, with the increased information regarding LDL (and specifically the small dense LDL particle) as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, no present consideration for LDL cholesterol as inclusion criteria for the metabolic syndrome is made. This article explores the role of LDL cholesterol as a cause and effect of complications with the metabolic syndrome in patients of these countries that are developing cardiovascular and metabolic diseases at an accelerated rate. Furthermore, as measurement of small dense LDL and apoprotein components becomes more widely available and cost effective, it may be that evaluation of these parameters and markers will assist the clinician and high-risk patient in the management and treatment of conditions that are associated with the metabolic syndrome.

Keywords

Metabolic syndrome; Low-density lipoprotein; Abdominal obesity; Hypertriglyceridemia

Life in the 21st century presents with an increased global incidence of metabolic and vascular events including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke and peripheral arterial disease. The prevalence of these diseases remains high in the United States, Canada, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and many European nations. Moreover, there is a substantial increase in the incidence of these disorders in developing countries (which include most Asian countries plus countries in Latin America and Africa), and the higher rate of these diseases is a result in part to a lifestyle that couples reduced physical activity with a moderate to high calorie intake. Moreover, this change in lifestyle seems to be the integral cause of the rapid increase in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome [1].

Metabolic syndrome is defined as a clustering of abdominal obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. Obesity guidelines based on Western populations markedly underestimate the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) among all Asians. This is because Asians have a greater body fat at a given BMI. The World Health Organization (WHO) has, therefore, issued a lower cutoff point for overweight (BMI>23) and obesity (BMI>25) for all Asians. Even among Caucasians, substantial risk of premature CAD occurs at a waist circumference (WC) of >90 cm underscoring the dangers of abdominal obesity. Conversely, Asian men and women tend to have more metabolic abnormalities at a lower waist circumference (WC) than Caucasians. The WHO and International Diabetes Federation (IDF) have also issued a lower cutoff point for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity through WC for Asian men (90 cm) and women (80 cm) [2].

Many Asians develop diabetes and metabolic syndrome with a body mass index (BMI) below 25 kg/m2, a figure which is considered normal among Caucasians. Furthermore, Asians tend to have more metabolic abnormalities at a lower waist circumference than Caucasians. The optimum WC among Chinese has been found to be 80 cm for both men and women. In Asian Indians WC is 85 cm for men and 80 cm for women [3]. Among South Asians, in comparison to criteria from the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP), the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome is higher by 30%-50% when criteria from the South Asian Modified National Cholesterol Program (SAM-NCEP) are applied. When utilizing SAM-NCEP criteria, the incidence of the metabolic syndrome in these individuals is higher by 20% in comparison to similar criteria from the International Diabetes Foundation [4].

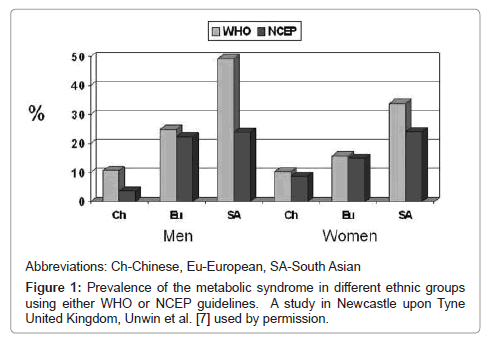

The figure below shows the prevalence in adults (25-64 years) from three ethnic groups who are residents in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. The comparisons and contrasts between the ethnic groups mainly reflect differences in the prevalence of diabetes and obesity. Although common by both WHO and NCEP definitions, agreement between the definitions is not particularly good [5].

From an observation analysis performed in Malaysia [6], the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher among Asian Indians (35.6%) compared to indigenous Sarawakians (30.5%), Malays (26.4%) and Chinese (26.2%). The prevalence of metabolic syndrome was higher among females (30.1%) compared to males (24.8%). Also, the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome was higher in individuals ≥ 40 years of age compared to those 15 to 40 years [7] (Figure 1).

The role of lipid abnormalities in diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been emphasized. Patients with type II diabetes mellitus generally present with a dyslipidemia that is characterized by elevated VLDL, small dense LDL particles and decreased HDL. In addition, Asians with an increase in WC are noted to have this pattern of dyslipidemia [4]. The percentage of individuals having a significant number of dense LDL particles is increased by at least twofold in type II diabetes mellitus. The prevalence of this qualitative abnormality of LDL has been reported to be surprisingly high, even in the absence of the characteristic diabetic dyslipidemia. Thus up to 45% of patients with low triglyceride (TG) levels and an even higher percentage of patients with borderline hypertriglyceridemia are known to have elevated levels of small dense LDL particle size [8,9]. The need for an early detection of risk factors in insulin resistant patients (with or without overt diabetes mellitus) should be emphasized in the medical setting.

Hypertriglyceridemia, one of the involved factors in the metabolic syndrome, reflects an increased concentration of any of several lipoproteins (including chylomicrons, VLDL & LDL). It has been observed that LDL (subclass B) is characterized by a preponderance of small dense LDL particles [9]. This is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and correlated with increased concentration of IDL (intermediate density lipoprotein)-C, VLDL-C, TG and low HDL-C levels. As hypertriglyceridemia is concomitant with increasing small LDL particles, hypertriglyceridemic matter gets replaced by small dense LDL particles [8]. An earlier hypothesis showed that prolonged presence of TG rich lipoproteins in the circulation leads to an increased exchange of their TG for IDL by cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP). TG enriched LDL is removed by hepatic lipase leading to the creation of small dense LDL.

The concentration of triglycerides correlates more closely with LDL size. It is known that TG concentration is inversely associated with LDL size (increased TG levels and small LDLs). We know that very small LDL size particles have the poorest LDL receptor binding [9]. Further, this type of LDL particle is considerably more susceptible to oxidation, thereby increasing the atherogenic risk. The triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol ratio may be related to the processes involved in LDL size, pathophysiology and relevant with regard to the risk of clinical vascular disease. This would prove helpful for the selection of patients needing early or aggressive treatment for dyslipidemias.

LDL cholesterol is well noted to be an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease. Conversely, it is not required that the LDL-C parameter be taken as part of the metabolic syndrome, primarily in high risk patient patients such as diabetes mellitus in which there is an increased amount of small dense LDL particles. An estimate of the qualification of small dense LDL particles can be predicted by a rough estimation of clinical and laboratory parameters. These markers include diabetes mellitus, HDL below 35 mg/dl, and triglycerides above 250 mg/dl. Any one of the three parameters that are present gives a very high indication of the presence of a large quantity of small dense LDL particles [9,10] (Figure 2).

Three prospective studies have established that small dense LDL is the best predictor of future coronary artery disease (CAD) in nondiabetic subjects, even after adjustment for confounding by TG, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol levels. Previous studies have established that LDL particles are small in nearly all subjects with low HDL cholesterol, whereas a normal HDL cholesterol level does not rule out the presence of small LDL particles. Moreover, alcohol consumption, dietary monounsaturated fatty acids, and physical activity can all modulate LDL size [10].

The weak relationship between LDL size and HDL cholesterol, a stronger relationship between LDL size and fasting triglyceride levels, and the presence of small LDL particles in patients with TG levels 1.65 mmol/l (60.55 mg/dl) have also been reported in other studies [10]. These data confirm that the prediction of LDL size by the triglyceride level only is not accurate when the triglyceride concentration is moderately increased and the HDL cholesterol level is normal. Various results raise a question: why is the ratio of TG to HDL cholesterol a better predictor of LDL size than either parameter alone? It has been firmly established that VLDL concentration assessed by fasting TG levels is a major determinant of LDL size. However, other mechanisms contribute to transformation of LDL and HDL particles-namely postprandial hypertriglyceridemia, cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity, and hepatic lipase activity. All induce a decrease in HDL and are abnormal in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Thus, for a given fasting triglyceride level, a lower HDL cholesterol level suggests that any of these three mechanisms is disturbing the lipoprotein metabolism. Therefore, any given fasting triglyceride level can be associated with a lower HDL cholesterol level and small LDL particles. A recent study has shown that LDL size is strongly associated with the TG-to-HDL cholesterol ratio; the present study has also established a cutoff point (TG-to-HDL cholesterol molar ratio of 1.33), allowing for a minimal degree of overlap between the two LDL size groups.

A second question relates to the relevance of the TG-to-HDL cholesterol ratio with regard to coronary risk. A case-control study has recently concluded that the ratio of TG to HDL is a strong predictor of myocardial infarction. With a risk factor, the case-control study has recently concluded that the ratio of TG to HDL is a strong predictor of myocardial infarction with a risk factor-adjusted relative the LDL particles may be small and the risk of CAD increased in patients with type 2 diabetes, even when the HDL cholesterol level is normal and TG level is 2.3 mmol/l (84.4 mg/dl). A TG-to-HDL cholesterol molar ratio 1.33 distinguishes the small and large LDL size pattern. This ratio may be used to identify diabetic patients with an atherogenic lipid profile and may be relevant for assessing CAD risk. Assessing small LDL-C in the laboratory would be ideal. Measurement of small dense LDL can be performed by a simplified ultracentrifugation procedure and immunoassay of apoproteins [11], and commercial laboratories are able to perform these procedures with high reproducibility and at a relatively inexpensive cost. In newly diagnosed patients both laboratory assessment and ratio may be useful for the selection of those who need aggressive lipid treatment early in the course of diabetes or before the onset of clinical cardiovascular disease [12].

Conclusion

There is growing evidence of small dense LDL as an important independent risk factor for atherosclerotic development and concomitant vascular diseases. The classic descriptors of the metabolic syndrome may not be applicable to all patients. Specifically, with the growing availability of the performance of this assay, high level of reproducibility, and decreasing cost, measurement of small dense LDL should be considered for inclusion criteria in the metabolic syndrome in certain high-risk patients. As increased availability is obtained on small dense LDL, this parameter could be used as a laboratory measurement in the determination of the metabolic syndrome.

References

- Enas EA, Mohan V, Deepa M, Farooq S, Pazhoor S, et al. (2007) The metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia among Asian Indians: a population with high rates of diabetes and premature coronary artery disease. J Cardiometab Syndr 2: 267-275.

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J; IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group (2005) The metabolic syndrome--a new worldwide definition. Lancet 366: 1059-1062.

- Deepa M, Farooq S, Datta M, Deepa R, Mohan V (2007) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome using WHO, ATPIII and IDF definitions in Asian Indians: the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-34). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 23: 127-134.

- Raji A, Seely EW, Arky RA, Simonson DC (2001) Body fat distribution and insulin resistance in healthy Asian Indians and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 5366-5371.

- Unwin N (2006) The metabolic syndrome. J R Soc Med 99: 457-462.

- Rampal S, Mahadeva S, Guallar E, Bulgiba A, Mohamed R, et al. (2012) Ethnic differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome: results from a multi-ethnic population-based survey in Malaysia. PLoS One 7: e46365.

- Unwin N, Bhopal R, Hayes L, White M, Patel S, et al. (2007) A comparison of the new international diabetes federation definition of metabolic syndrome to WHO and NCEP definitions in Chinese, European and South Asian origin adults. Ethn Dis 17: 522-528.

- Kondo A, Muranaka Y, Ohta I, Notsu K, Manabe M, et al. (2001) Relationship between triglyceride concentrations and LDL size evaluated by malondialdehyde-modified LDL. Clin Chem 47: 893-900.

- Grundy SM (1997) Small LDL, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome. Circulation 95: 1-4.

- Musunuru K (2010) Atherogenic dyslipidemia: cardiovascular risk and dietary intervention. Lipids 45: 907-914.

- Menys VC, Liu Y, Mackness MI, Caslake MJ, Kwok S, et al. (2003) Measurement of plasma small-dense LDL concentration by a simplified ultracentrifugation procedure and immunoassay of apolipoprotein B. Clin Chim Acta 334: 95-106.

- Boizel R, Benhamou PY, Lardy B, Laporte F, Foulon T, et al. (2000) Ratio of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol is an indicator of LDL particle size in patients with type 2 diabetes and normal HDL cholesterol levels. Diabetes Care 23: 1679-1685.

--

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14410

- [From(publication date):

November-2013 - Apr 05, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9875

- PDF downloads : 4535