A Brief Review of the Controversial Role of Iron in Colorectal Carcinogenesis

Received: 29-Mar-2013 / Accepted Date: 29-Apr-2013 / Published Date: 01-May-2013 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000137

Abstract

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) is the second and third most common cancer in females and males worldwide,

respectively. Major risk factors have been established for the development of CRC. These include susceptible

genetics, increased age (50 years), male gender, and race. The role of environmental factors in CRC pathogenesis

is evident but complex. Some environmental factors linked to CRC pathogenesis include diet, specifically red meat,

refined grains and starches, sugars, fat, alcohol, and chemicals. Implicated chemicals include arsenic, chromium,

nickel and iron. This article briefly reviews the evidence for the controversial role of iron in pathogenesis of CRC.

Proposed mechanisms for iron carcinogenesis involve various genetic and metabolic pathways, illustrating the

complex interplay of genetic and metabolic alterations in chemical carcinogenesis

Keywords: Iron; Colorectal cancer; Chemical carcinogenesisv

308940Introduction

Colorectal Cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in males and the second in females worldwide with over 1.2 million new cases and over 600,000 estimated deaths in 2008 [1]. In the United States, it is estimated that 142,820 new cases of CRC with over 50,000 deaths occur annually [2]. The development of CRC has been shown to be related to individual’s genetics and environmental factors. The genetic effect on the development of sporadic CRC is reflected by different incidences occurring based on age, sex, and ethnicity [3]. About 10-15 % of CRC are solely attributable to genetic abnormalities. Hereditary CRC syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) are two of these examples [4-7].

The development of sporadic CRCs, comprising the majority of cases, has been linked to many environmental factors. These exogenous factors include high intake of red and processed meats, highly refined grains and starches, sugars, fat and alcohol consumption [8,9]. Certain chemicals are also implicated in carcinogenesis. Among them, high iron consumption has been associated with an increased risk of CRC [10]. One study has demonstrated serum transferrin saturation (a surrogate for iron overload) as a strong independent marker for the presence of colon adenomas, precursors of colon cancer [11]. Other studies, however, showed no such association and that iron deficiency is possibly linked to gastrointestinal carcinogenesis by increased oxidative stress, DNA damage, and impairment of iron-dependent metabolic functions related to genome repair and protection [12]. This review will focus on iron overload as a controversial risk factor in colon carcinogenesis.

Iron and Colorectal Cancer

Iron is required for proliferation of normal and neoplastic cells [13-17]. The relationship between iron and cancer risk appears to be more obvious in the colon due to its high concentrations of iron. It has been suggested that the protective effect of dietary fiber observed in human colorectal cancer may be due to iron chelation by phytic acid in dietary fiber [18,19]. The Haber-Weiss cycle that results in synthesis of hydroxyl radical and other oxidants has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo, and for iron delivered parenterally or enterally [18]. Multiple epidemiologic studies have shown a positive correlation between iron and colorectal cancer, including examination of effects of genetics, dietary fiber, dietary iron, and total body iron stores [10,13,14,20,21].

In a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies of the risk of colorectal carcinoma conferred by increased body iron load, approximately three quarters of 33 studies supported the association of iron with colorectal cancer risk [18,22]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I study (1971 - 1984) showed that iron s

tores were higher in 242 men who developed cancer than in 3113 men who were cancer free [18]. Total iron binding capacity (TIBC) and transferrin saturation (Tf sat.) were measured. Colon, esophagus, lung, and bladder cancers were the neoplasms associated with iron overload. The follow-up study by Wurzelman et al. [10] also showed a positive association between dietary and body iron stores with colorectal cancer [10,22]. Several prospective studies have also shown a positive correlation between various indices of increased body iron stores and colorectal cancer [10,13,14,20,21,23]. More evidence for the role of iron overload in the pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma comes from the observation that the relative risk of colorectal cancer was substantially increased in hereditary hemochromatosis and in individuals who are either heterozygotes or homozygotes for Hemochromatosis Fe (HFE) gene [10,24,25].

Some studies have found that there is no association between the risk of colorectal cancer and body iron levels or dietary iron uptake [26,27], and that iron supplement or serum ferritin concentration is not linked to the recurrence of colorectal adenoma [27,28]. Negative associations between the risk of colorectal cancer and body iron levels or dietary iron uptake has also been reported, including one nested case–control study in women [29]. Kato et al. [29] found an inverse association with risk of colorectal cancer with one of the biomarkers for body iron stores, although there was a weak correlation with increased iron intake and an increased risk of colorectal cancer in certain subgroups, including subjects with higher fat intake [29]. Most recently, Cross et al., found a significant inverse association between several serum iron indices (serum ferritin, serum iron and transferring saturation) and colon cancer risk in a nested case-control study within the alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene cancer prevention study cohort which included 130 colorectal cancer cases and based on a 276-item food frequency questionnaire [30]. Cross et al. [30] however, found the serum Unsaturated Iron Binding Capacity (UIBC) associated with an elevated risk for colon cancer.

In addition to association with colorectal cancer, studies have found that iron overload also has a positive relationship with the development of precancerous lesions. There is evidence showing that unabsorbed dietary iron increases free radical production in the colon to a level that could cause damage to the mucosa and crypt cell proliferation [31,32]. Results from animal studies showed that iron supplementation in rats led to cytotoxic events. These cytotoxic events include decreased manganese superoxide dismutase activity, increased lipid peroxidation and free radical generating capacity in the colon and cecum, and elevated colonic aberrant crypt foci [22,33-37]. Cytoplasmic staining for the iron storage protein ferritin was detected in both colonic adenoma and colorectal cancer, and expression of ferritin has been found to be positively associated with the degree of dysplasia and tumor size [38]. Examination of resected polyps and colorectal carcinomas showed an association of colonic adenoma progression to carcinoma with an increased expression of iron import proteins and a decreased expression of iron export proteins [39,40].

Controversial association between body iron load and colorectal carcinogenesis is listed in (Table 1).

| Correlation | Summary | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Elevated serum iron was associated with increased risk, strongest in the distal colon and significant in females. Mean transferrin saturation was higher in cases compared to controls (30.7 versus 28.7%), but TIBC did not predict the occurrence of colorectal cancer. | [10] |

| Mean transferrin saturation and differences in TIBC and serum iron were higher in men who developed cancer than those who did not. When divided into 5 groups on the basis of baseline transferrin saturation, the combined risk of cancer occurrence associated with moderate elevations. | [13] | |

| Mean total iron-binding capacity was significantly lower and transferrin saturation was significantly higher than men who remained free of cancer. The risk of cancer in men in each quartile of transferrin-saturation level relative to the lowest quartile rose incrementally. Among women, a post hoc examination associated with very high transferrin saturation. | [14] | |

| Mortality in postmenopausal women was inversely related to TIBC; the relative risk for the highest tertile of TIBC, adjusted for age, smoking and alcohol intake was 0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.007-0.39). There was association between body iron stores and mortality due to cancer was observed in men. | [20] | |

| Excess risk of colorectal was found in subjects with transferrin saturation level exceeding 60%. The adjusted relative risk was 3.04 for colorectal cancer. High iron stores may increase the risk of colorectal cancer. | [21] | |

| Elevated relative risk was observed in hereditary hemochromatosis heterozygotes in males for colorectal cancer (RR, 1.28; CI, 1.07-1.53), colonic adenoma (RR, 1.29; CI, 1.08-1.53 for females and 1.24; CI, 1.05-1.46 for males), and stomach cancer in females (RR, 1.37; CI, 1.04-1.79). | [24] | |

| Individuals carrying the HFE Tyr282 allele (homo- and heterozygotes) in combination with homozygosity for the TFR Ser142 allele are at increased risk for neoplasia, including colorectal cancer. The odds ratio for three neoplasms (including CRC) increased for HFE Tyr homozygotes and compound heterozygotes in combination with TFR Ser homozygosity. | [25] | |

| There was a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer associated with higher total iron intake [odds ratio (OR) = 2.50; 95% confidence interval (CI) suggesting a role of luminal exposure to excessive iron but does not support a role for increased body iron stores in CRC development. | [29] | |

| Negative | There were no associations between the risk of colorectal cancer and any serum iron indices except for serum ferritin, which showed a significant inverse association. This suggests a role of luminal exposure to excessive iron but does not support a role for increased body iron stores in CRC development. | [29] |

| There was an inverse association between serum ferritin, iron and transferrin and colorectal cancer risk and a suggestion of an inverse association between dietary iron and colorectal cancer risk. However, serum unsaturated iron binding capacity was positively associated with colon cancer risk. | [30] | |

| No association | In men, transferrin saturation was inversely associated with risk of colon and rectal carcinoma. No cases observed with transferrin saturation. There was no evidence that the risk of epithelial cancer (all sites combined) is related to transferrin saturation level or to iron deficiency (≤5%) or overload (≥60%). | [26] |

Table 1: Summary of association between body iron load and the development of colorectal cancer.

Mechanisms of Iron-mediated Carcinogenesis

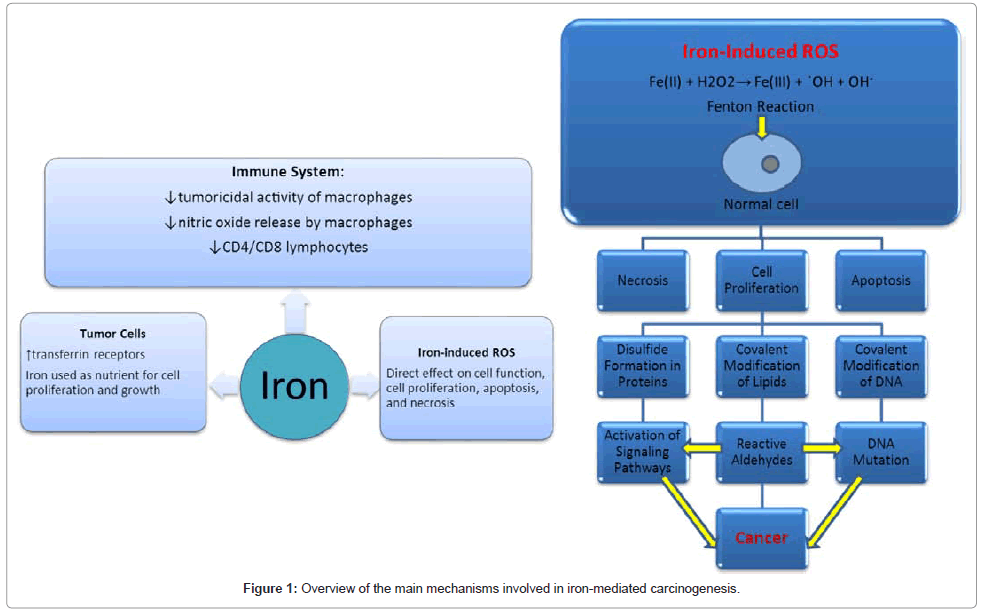

In the colon, iron increases the production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) from peroxidases via the Fenton reaction, which may cause cellular toxicity and pro-mutagenic lesions [41-43]. Lipids, DNA, and proteins are targeted by these ROS. Iron-overload was shown to induce oxidative DNA damage in the form of DNA breaks and oxidized bases in the human colon carcinoma cell line HT29 clone 19A when the tumor cells were incubated with ferric-nitrilotriacetate (Fe-NTA) or with hemoglobin [42]. Hemoglobin was used as a source of physiological iron and was found to be as efficient in inducing DNA damage as Fe-NTA in a clear-cut concentration-effect relationship [42]. DNA damage incubated with Fe-NTA or with hemoglobin was two-six folds of the control [42]. Iron increased damage two-three folds over the control at concentration which have been reported to be physiologically available (200-500μM) [17,42]. It has also been demonstrated that cells localized near the stem cells of the colon crypt were more susceptible to oxidative stress than colon cells located on the luminal part of the crypt [44].

Recent studies also suggest that iron-mediated ROS may target specific genes in Fenton reaction-induced cancer. A Fe-NTA-induced rat Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC) model showed increased numbers of oxidatively modified DNA bases including 8-oxoguanine and a major lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal [45-47]. Gpt delta transgenic mice showed deletion and single nucleotide substitutions at G:C sites to be preferred mutations in the kidney treated with Fe-NTA [45,48]. Microsatellite analysis in F1 hybrid rats revealed that p15 and p16 tumor suppressor genes were targeted and either homozygously deleted or methylated at the promoter region [49]. This led to the proposal of ‘fragile’ sites in the genome susceptible to oxidative stress [45]. Gene expression microarray and array-based comparative genome hybridization analyses identified target oncogenes in Fe-NTAinduced RCC. A tyrosine phosphatase, ptprz1, was found to be highly expressed in RCC and at the chromosomal region of amplification (4q22). This model showed that iron-mediated oxidative stress induced genomic amplification of ptprz1 which results in activation of β-catenin pathways during carcinogenesis [45,50].

It has also been proposed that iron can induce early signaling pathways that modulate activities of oxidative-responsive transcription factors such as activator protein 1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF?B) [22]. AP-1 and NF?B binding sites are found in promoters of many genes such as interleukin-6 (IL-6). Activation of these transcription factors may lead to upregulation of cytokine genes, and over-expression of IL-6 caused by iron may lead to chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis [22,51].

Other possible mechanisms for iron carcinogenesis include effects of iron on the immune system. Tumoricidal activity of macrophages was markedly suppressed by phagocytosed erythrocytes, erythrocyte lysate, hemoglobin, iron salts or iron dextran [22,52]. The ratio of CD4 and CD8 positive lymphocytes were lowered by iron [53]. Studies in mice have also shown iron to reduce both macrophage and tumor cellsderived nitric oxide release, which promotes carcinogenesis [54].

Iron itself may facilitate cancer growth by serving as a nutrient. Iron is required for cell proliferation and is a constituent of proteins that catalyze key reactions including oxygen sensing, energy metabolism, respiration, and DNA synthesis [22,55]. Tumor cells express more transferrin receptors, resulting in higher cellular iron uptake for growth than normal cells [22].

Another interesting aspect of iron carcinogenesis is the synergistic effect iron may have with non-amidated gastrins in the development of CRC. Non-amidated gastrins include progastrin and Ggly. CRCs have been found to express progastrin in greater amounts than normal colon cells, and patients with CRC have increased circulating concentrations of Gamide and total gastrins [40,56,57]. It has also been recognized that ferric ions were essential for the biological activities of non-amidated gastrins with the proposal that gastrins catalyze the loading of transferrin with iron [40]. Although precise mechanisms underlying the involvement of gastrins in iron homeostasis are unknown, this synergistic effect of non-amidated gastrins and iron on CRC development is strongly suggested [40]. Figure 1 summarizes the main mechanisms involved in iron-mediated carcinogenesis.

Conclusion

Many epidemiologic and experimental studies have shown a positive association between dietary and body iron stores with the development of colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions. However, the risk of iron intake for the development of CRC is controversial. There are a few studies showing no association between the risk of colorectal cancer and body iron levels or dietary iron uptake and that iron supplement or serum ferritin concentration is not linked to the recurrence of colorectal adenoma. Inverse associations between the risk of colorectal cancer and body iron levels or dietary iron uptake have also been reported.

The mechanisms of possible iron carcinogenesis are not unclear. Based on in vitro evidence, it is proposed that iron can induce early signaling pathways that modulate oxidative-responsive transcription factors, or that iron suppresses tumoricidal activity of macrophages and lowers the ratio of CD4 and CD8 positive lymphocytes. Emerging research shows that certain genomic sequences may be vulnerable to oxidative damage. This illustrates the complex interplay of genetic and metabolic alterations in chemical carcinogenesis.

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61: 69-90.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 63: 11-30.

- Eddy DM (1990) Screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 113: 373-384.

- Burt RW, DiSario JA, Cannon-Albright L (1995) Genetics of colon cancer: impact of inheritance on colon cancer risk. Annu Rev Med 46: 371-379.

- Lynch HT, Smyrk TC, Watson P, Lanspa SJ, Lynch JF, et al. (1993) Genetics, natural history, tumor spectrum, and pathology of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: an updated review. Gastroenterology 104: 1535-1549.

- Atkin WS, Morson BC, Cuzick J (1992) Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. N Engl J Med 326: 658-662.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF (2012) Risk for colorectal cancer in persons with a family history of adenomatous polyps: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 156: 703-709.

- Chan AT, Giovannucci EL (2010) Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 138: 2029-2043.

- Bingham SA (1996) Epidemiology and mechanisms relating diet to risk of colorectal cancer. Nutr Res Rev 9: 197-239.

- Wurzelmann JI, Silver A, Schreinemachers DM, Sandler RS, Everson RB (1996) Iron intake and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 5: 503-507.

- Muthunayagam NP, Rohrer JE, Wright SE (2009) Correlation of iron and colon adenomas. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 33: 435-440.

- Prá D, Rech Franke SI, Pegas Henriques JA, Fenech M (2009) A possible link between iron deficiency and gastrointestinal carcinogenesis. Nutr Cancer 61: 415-426.

- Stevens RG, Graubard BI, Micozzi MS, Neriishi K, Blumberg BS (1994) Moderate elevation of body iron level and increased risk of cancer occurrence and death. Int J Cancer 56: 364-369.

- Stevens RG, Jones DY, Micozzi MS, Taylor PR (1988) Body iron stores and the risk of cancer. N Engl J Med 319: 1047-1052.

- Stevens RG, Kalkwarf DR (1990) Iron, radiation, and cancer. Environ Health Perspect 87: 291-300.

- Weinberg ED (1984) Iron withholding: a defense against infection and neoplasia. Physiol Rev 64: 65-102.

- Weinberg ED (1996) The role of iron in cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev 5: 19-36.

- Nelson RL (1992) Dietary iron and colorectal cancer risk. Free Radic Biol Med 12: 161-168.

- Graf E, Eaton JW (1985) Dietary suppression of colonic cancer. Fiber or phytate? Cancer 56: 717-718.

- van Asperen IA, Feskens EJ, Bowles CH, Kromhout D (1995) Body iron stores and mortality due to cancer and ischaemic heart disease: a 17-year follow-up study of elderly men and women. Int J Epidemiol 24: 665-670.

- Knekt P, Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Aromaa A, Heliövaara M, et al. (1994) Body iron stores and risk of cancer. Int J Cancer 56: 379-382.

- Huang X (2003) Iron overload and its association with cancer risk in humans: evidence for iron as a carcinogenic metal. Mutat Res 533: 153-171.

- Freudenheim JL, Graham S, Marshall JR, Haughey BP, Wilkinson G (1990) A case-control study of diet and rectal cancer in western New York. Am J Epidemiol 131: 612-624.

- Nelson RL, Davis FG, Persky V, Becker E (1995) Risk of neoplastic and other diseases among people with heterozygosity for hereditary hemochromatosis. Cancer 76: 875-879.

- Beckman LE, Van Landeghem GF, Sikström C, Wahlin A, Markevärn B, et al. (1999) Interaction between haemochromatosis and transferrin receptor genes in different neoplastic disorders. Carcinogenesis 20: 1231-1233.

- Herrinton LJ, Friedman GD, Baer D, Selby JV (1995) Transferrin saturation and risk of cancer. Am J Epidemiol 142: 692-698.

- Tseng M, Sandler RS, Greenberg ER, Mandel JS, Haile RW, et al. (1997) Dietary iron and recurrence of colorectal adenomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 1029-1032.

- Tseng M, Greenberg ER, Sandler RS, Baron JA, Haile RW, et al. (2000) Serum ferritin concentration and recurrence of colorectal adenoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9: 625-630.

- Kato I, Dnistrian AM, Schwartz M, Toniolo P, Koenig K, et al. (1999) Iron intake, body iron stores and colorectal cancer risk in women: a nested case-control study. Int J Cancer 80: 693-698.

- Cross AJ, Gunter MJ, Wood RJ, Pietinen P, Taylor PR, et al. (2006) Iron and colorectal cancer risk in the alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene cancer prevention study. Int J Cancer 118: 3147-3152.

- Lund EK, Wharf SG, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Johnson IT (1998) Increases in the concentrations of available iron in response to dietary iron supplementation are associated with changes in crypt cell proliferation in rat large intestine. J Nutr 128: 175-179.

- Lund EK, Wharf SG, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Johnson IT (1999) Oral ferrous sulfate supplements increase the free radical-generating capacity of feces from healthy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr 69: 250-255.

- Davis CD, Feng Y (1999) Dietary copper, manganese and iron affect the formation of aberrant crypts in colon of rats administered 3,2'-dimethyl-4-aminobiphenyl. J Nutr 129: 1060-1067.

- Kuratko CN (1997) Increasing dietary lipid and iron content decreases manganese superoxide dismutase activity in colonic mucosa. Nutr Cancer 28: 36-40.

- Liu Z, Tomotake H, Wan G, Watanabe H, Kato N (2001) Combined effect of dietary calcium and iron on colonic aberrant crypt foci, cell proliferation and apoptosis, and fecal bile acids in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-treated rats. Oncol Rep 8: 893-897.

- Lund EK, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Wharf SG, Johnson IT (2001) Chronic exposure to high levels of dietary iron fortification increases lipid peroxidation in the mucosa of the rat large intestine. J Nutr 131: 2928-2931.

- Sesink AL, Termont DS, Kleibeuker JH, Van der Meer R (1999) Red meat and colon cancer: the cytotoxic and hyperproliferative effects of dietary heme. Cancer Res 59: 5704-5709.

- Yang HB, Hsu PI, Lee JC, Chan SH, Lin XZ, et al. (1995) Adenoma-carcinoma sequence: a reappraisal with immunohistochemical expression of ferritin. J Surg Oncol 60: 35-40.

- Brookes MJ, Hughes S, Turner FE, Reynolds G, Sharma N, et al. (2006) Modulation of iron transport proteins in human colorectal carcinogenesis. Gut 55: 1449-1460.

- Kovac S, Anderson GJ, Baldwin GS (2011) Gastrins, iron homeostasis and colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1813: 889-895.

- Aruoma OI, Halliwell B, Gajewski E, Dizdaroglu M (1989) Damage to the bases in DNA induced by hydrogen peroxide and ferric ion chelates. J Biol Chem 264: 20509-20512.

- Glei M, Latunde-Dada GO, Klinder A, Becker TW, Hermann U, et al. (2002) Iron-overload induces oxidative DNA damage in the human colon carcinoma cell line HT29 clone 19A. Mutat Res 519: 151-161.

- Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S (1988) Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240: 640-642.

- Liegibel UM, Abrahamse SL, Pool-Zobel BL, Rechkemmer G (2000) Application of confocal laser scanning microscopy to detect oxidative stress in human colon cells. Free Radic Res 32: 535-547.

- Toyokuni S (2009) Role of iron in carcinogenesis: cancer as a ferrotoxic disease. Cancer Sci 100: 9-16.

- Toyokuni S, Mori T, Dizdaroglu M (1994) DNA base modifications in renal chromatin of Wistar rats treated with a renal carcinogen, ferric nitrilotriacetate. Int J Cancer 57: 123-128.

- Toyokuni S, Uchida K, Okamoto K, Hattori-Nakakuki Y, Hiai H, et al. (1994) Formation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-modified proteins in the renal proximal tubules of rats treated with a renal carcinogen, ferric nitrilotriacetate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 2616-2620.

- Jiang L, Zhong Y, Akatsuka S, Liu YT, Dutta KK, et al. (2006) Deletion and single nucleotide substitution at G:C in the kidney of gpt delta transgenic mice after ferric nitrilotriacetate treatment. Cancer Sci 97: 1159-1167.

- Tanaka T, Iwasa Y, Kondo S, Hiai H, Toyokuni S (1999) High incidence of allelic loss on chromosome 5 and inactivation of p15INK4B and p16INK4A tumor suppressor genes in oxystress-induced renal cell carcinoma of rats. Oncogene 18: 3793-3797.

- Liu YT, Shang D, Akatsuka S, Ohara H, Dutta KK, et al. (2007) Chronic oxidative stress causes amplification and overexpression of ptprz1 protein tyrosine phosphatase to activate beta-catenin pathway. Am J Pathol 171: 1978-1988.

- Coussens LM, Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420: 860-867.

- Weinberg JB, Hibbs JB Jr (1977) Endocytosis of red blood cells or haemoglobin by activated macrophages inhibits their tumoricidal effect. Nature 269: 245-247.

- Reddy MB, Clark L (2004) Iron, oxidative stress, and disease risk. Nutr Rev 62: 120-124.

- Harhaji L, Vuckovic O, Miljkovic D, Stosic-Grujicic S, Trajkovic V (2004) Iron down-regulates macrophage anti-tumour activity by blocking nitric oxide production. Clin Exp Immunol 137: 109-116.

- Le NT, Richardson DR (2002) The role of iron in cell cycle progression and the proliferation of neoplastic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1603: 31-46.

- Ciccotosto GD, McLeish A, Hardy KJ, Shulkes A (1995) Expression, processing, and secretion of gastrin in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 109: 1142-1153.

- Van Solinge WW, Nielsen FC, Friis-Hansen L, Falkmer UG, Rehfeld JF (1993) Expression but incomplete maturation of progastrin in colorectal carcinomas. Gastroenterology 104: 1099-1107.

Citation: Cho M, Eze OP, Xu R (2013) A Brief Review of the Controversial Role of Iron in Colorectal Carcinogenesis. J Clin Exp Pathol 3:137. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0681.1000137

Copyright: © 2013 Cho M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16767

- [From(publication date): 2-2013 - Dec 19, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 12134

- PDF downloads: 4633